The original question was Adolf Hitler’s to General Alfred Jodl in August 1944, but the French had long had good reason to fear the answer. In a previous post I quoted Gustaf Janson’s pre-World War I fantasy of a future air raid on Paris:

‘Unexpectedly, without any warning dynamite begins to rain down on the city. Each explosion follows on the heels of the last. Hospitals, theatres, schools, museums, public buildings, private houses – all are demolished. Roofs collapse, floors fall into cellars, the streets are blocked with the ruins of houses. The sewers break and pour their foul contents over everything. The water pipes burst, flooding begins. The gas mains rupture, gas streams out, explodes, starts fires. The electric light goes out… Above it all can be heard the detonations exploding with mathematical precision…. Men, women, children, insane with terror, wander among the ruins…. When the last flying machine has dones its work and turned northwards again, the bombardment is finished. In Paris a stillness reigns such as never reigned before.’

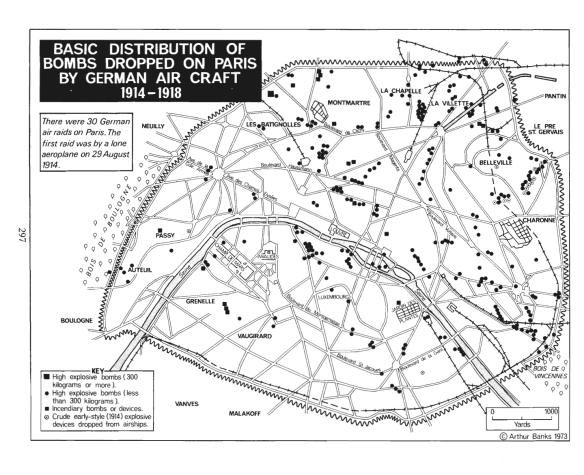

While the First World War did not see such a devastating attack on the city, there were repeated bombardments. Paris was, after all, closer to the front than any of the other belligerent capitals. Historian Susan Grayzel provides a careful chronology of air raids on Paris in ‘The souls of soldiers”: civilians under fire in First World War France’ (Journal of modern history 78 (2006) 588-622), and it’s clear that the major bursts of activity were at the beginning and the end of the war: August-October 1914 and a crescendo between January-September 1918. All told, Grayzel’s tabulations (from Jules Poirier’s Bombardements de Paris) show that attacks from German aircraft killed 275 people and injured 610 in the city and in the banlieu.

On 30 August 1914 a two-seater German Taube (‘Dove’) aircraft circled in the sky over Paris, and at 12.45 p.m. began to drop the first of four 5lb. bombs. The final ‘bomb’ was a sack of sand with a message attached: ‘The German Army is at your gates. You can do nothing but surrender.’ This was the first propaganda drop in aviation history and, like most subsequent leafleting raids, had little effect.

But the Germans continued to send Tarben over the city at regular intervals – and in fact at the same time each day. The regularity turned the flights into a routine for Parisians too: see the images here. Emmanuelle Cronier (in Capital cities at war, vol. 2, eds. Jay Winter and Jean-Louis Robert, Cambridge University Press, 2007) provides a sketch of their impact (or lack of it):

‘At “Taube time”, around 5.00 p.m., a new urban ritual developed, replacing the pre-war Parisian’s characteristic stroll with gatherings on balconies in squares, on bridges or promontories. Those with binoculars scanned the sky: “There’s one!” shouted a man. Next the Taube is insulted, French aircraft are launched in pursuit, applauded… To some eyes this Parisian defiance of the Tauben constituted the true expression of the Paris crowd… Because these light German bombs claimed few victims, perception of the danger was deferred. It was not until the arrival of the Zeppelins in March 1915 that the people of Paris understood the reality of the threat.’

In September 1914 the German advance towards Paris was accompanied by night raids by Tauben. After the battle of the Marne, when the advance was finally rebuffed, the capital returned to something approaching its pre-war life. So much so, indeed, that many French soldiers on leave must have identified with the complaint voiced in Henri Barbusse‘s Le feu (1916), cited in Alistair Horne’s Seven ages of Paris (Knopf, 2002):

‘We are divided into two foreign countries. The front, over there, where there is too much misery, and the rear, here, where there is too much contentment.‘

Air war undoes those separations, of course, and soon commentators were drawing attention to the fact. Grayzel cites Le Petit Parisien in March 1915:

‘It’s not a trait of bravery to go dropping bombs in sleeping civilians, to profit from darkness, like a vulgar bandit … in order to assassinate women and children in their [homes].’

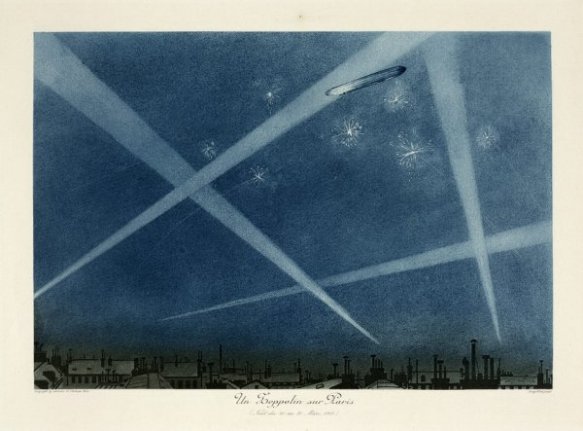

By then Zeppelins had made their far more sinister appearance in the night skies, and a black-out was imposed on the ‘City of Light’. Here is one eyewitness report of the first raid on 21 March 1915 from a woman living near the Eiffel Tower:

“I was awakened by firemen’s bugles, and as we had all been warned I had no doubt what the noise meant. I dressed and hesitated whether to leave my flat on the top story, but decided to stay and see what was going to happen. I watched the police trying to extinguish a gas jet in the road below, which gave them a great deal of trouble. Then for a long time nothing happened. The night was so clear and peaceful, it seemed impossible that there could be any danger.

“Suddenly there came reports from distant guns, and then a series of vivid flashes from behind houses at no great distance, followed by a violent cannonade which made the windows rattle.

“Searchlights were playing in all directions, but at first nothing was visible except the ghostly outline of the Eiffel Tower. Then I noticed that several stars were obscured by what seemed to be a long grey cloud moving at a tremendous rate. It seemed more like a shadow than anything solid. What struck me most about it was its enormous length and extraordinary speed. When a searchlight fell on it, it was only a fraction of a second before it passed out of its field. I knew at once it was a Zeppelin. As we had been forbidden to show any light, I lit a match in a corner of the room, and looked at my watch. It was ten minutes to two.

“When I went back to the window the firing had increased in intensity, and the airship, which was far away behind the Eiffel Tower at what seemed a very great altitude, appeared to be replying to the guns. From below the long grey shadow came a series of flashes, so that I think it must have been firing machine guns at the guns firing at it. Then, suddenly, the airship disappeared like a cloud, as suddenly and mysteriously as it had come. The firing ceased and all was still for ten minutes, when everything began over again, the guns again opening fire on what was, I suppose, a second Zeppelin. This airship, however, disappeared quicker than the first.”

As Grayzel shows, contemporary reports were part of an elaborate construction of Paris as an ‘innocent, heroic, feminized city’, and the phallic Zeppelin was turned into a faux, puffed-up masculinity that was contrasted with the ‘real’ masculinity (and by extension the ‘real’ war) of ‘hand-to-hand combat with bayonets’.

There were immediate calls for reprisals. Le Figaro offered its readers a stark choice: ‘Either we resign ourselves to accepting more and more frequently the insults these Zeppelins show us, or we decide to carry to the other side of the Rhine all the horrors of the air war.’ But, as Andrew Barros shows in ‘Strategic bombing and restraint in “Total War”, 1915-1918’ (Historical Journal 52 (2009) 413-31), French strategic bombing was remarkably restrained throughout the war, and ‘reprisal raids’ were carefully calibrated – partly for reasons of geography (the quotations below are also from Pétain):

‘German bombers had to travel short distances to strike French cities, often just 30 kilometres. French targets in Germany were located well past the zone of occupation, often 150 to 200 kilometres behind the lines. Bombing a city like Frankfurt was “incomparably more difficult for the Allies” than it was for the Germans to attack Paris, especially because to have any substantive effect, raids needed to be conducted in a massive way and frequently repeated.’

The restrictions on bombing were also prompted by fears of escalation: ‘Requests from flying officers for permission to conduct reprisal raids against Berlin, Hamburg, Cologne and even Constantinople were repeatedly turned down by the army command.’

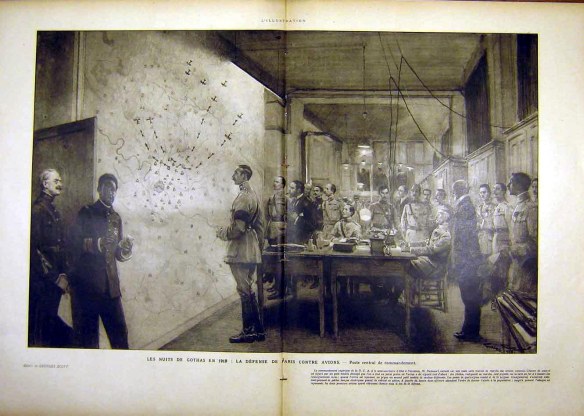

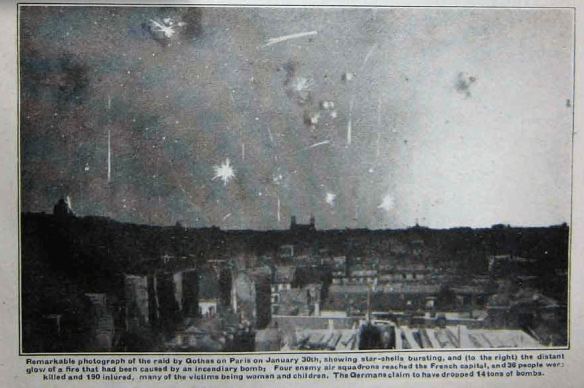

It was not until 1918 – and particularly during Ludendorff’s renewed ground offensive against the city – that, as Grayzel has it, ‘full-scale war came to Paris.’ According to Lee Kennett (The First Air War, 1914-1918) the German high command described the attacks carried out by Gotha bombers as Vergeltungsmassnahmen – reprisals for Allied attacks on cities ‘outside the region of operations’ like Mannheim and Freiburg – but they were clearly part of the calculated offensive: probes of Paris’s air defences were made in January, and the main attacks started in March. Kennett notes that ‘the French met them with searchlights, anti-aircraft guns, night fighters and a cordon of barrage balloons that forced the bombers to come in over 3,000 meters – a height that ruled out any bombing accuracy.’ The resources commanded by Paris’s Défense Contre Avions (DCA) were much greater in 1918 than 1914 ,and the response was more carefully co-ordinated –

– but the threat was also much greater. The Gothas were much faster and more manoeuvrable than the airships, cruising at around 80 m.p.h. They had a much smaller bomb load – it took six aircraft to deliver the same load as one Zeppelin – but if they could fly at lower altitudes at night they could almost double their standard daylight bomb load of around 660 lbs. The raids were also on a much larger scale and were carried out with far greater intensity than previous attacks, though targeting was still very haphazard. One French expert told the New York Times (for its 19 March edition) that

‘it was practically impossible to strike any particular objective when a plane was travelling at a rate of thirty-eight to forty yards a second. A bomb must be dropped more or less at random, which is the reason why such form of warfare is simply criminal. It is impossible to tell where the bomb will fall.’

The blackout was reintroduced, but it was only partially effective. The Associated Press reported on 22 March that 1500 prosecutions for violations of the new restrictions had been launched in just two days in an attempt to produce a ‘darker Paris’. But the offenders were not confined to a careless public.

‘On the Ile de la Cité more than thirty windows were illuminated in the Palais de Justice, where all appeals from convictions in the lighting cases will be heard. Light was also shining brilliantly from a dozen windows of the Prefecture of Police, from which was issued the order for darkening the city.’

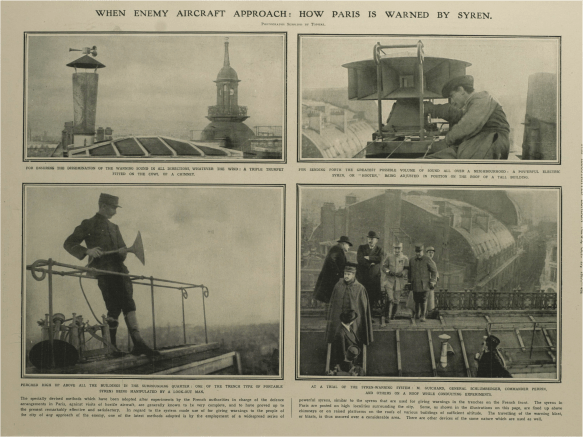

Firemen’s bugles were no longer adequate to warn the public and new air raid sirens were installed – a sufficient novelty to spark a feature in the Illustrated London News (below): since July 1917 Britain had relied on a system of marine distress maroons to warn of approaching enemy aircraft, supplemented by Boy Scouts with bugles and policemen with placards and whistles – and Parisians now regularly took shelter in cellars or in public shelters (there were 5,000 of them).

The attacks caused widespread damage – there is a sheaf of photographs here from Parisienne de Photographie (scroll down) – and yet the first reports were often once again remarkably nonchalant. Here is Charles Grasty reporting from Paris on 23 March 1918 for the New York Times:

The attacks caused widespread damage – there is a sheaf of photographs here from Parisienne de Photographie (scroll down) – and yet the first reports were often once again remarkably nonchalant. Here is Charles Grasty reporting from Paris on 23 March 1918 for the New York Times:

‘Paris was out en fête to receive the Gothas this morning… Last night there was considerable excitement following the alarm, but this morning there was more of a picnic spirit. As I write, at 10.30 at the Matin office, there is an explosion as of a bomb around the corner. Through the open window I see people on the roofs across the boulevard scanning the cloudless Springlike skies. At the Ritz and other hotels many guests assembled downstairs but there was not the slightest panic.

I walked through the Rue de la Paix with Ridgely Carter and found the Place de l’Opéra crowded, everybody looking up as if watching some astronomical phenomenon. Many taxis were standing in rank in the Boulevard des Italiens but the chauffeurs had all left them to join the gazer sin the square.

Paris is puzzled as the air raid proceeds. The occasional explosion of a bomb makes the town aware of the continued presence of the Gothas, but the affair is quite casual and lacking in violence.’

The date was auspicious. The explosion that morning in the Place de la République seemed (im)perfectly ordinary, and the DCA assumed that the city had suffered another air raid.

But by the end of the day, as explosions continued at regular intervals and 16 people lay dead, it became clear that Paris was under artillery fire. The DCA plotted the trajectory of fire from the locations of the first explosions, and sent aircraft to find the source. The battery was hidden in the forest of Courcy, an unimaginable 120 kilometres away, and Krupp’s long-range siege gun continued to shell the city until August, scattering some 20 shells across Paris each day. This new ‘fire on Paris’ killed 250 people and caused widespread damage, but had little effect on everyday life in the city.

But by the end of the day, as explosions continued at regular intervals and 16 people lay dead, it became clear that Paris was under artillery fire. The DCA plotted the trajectory of fire from the locations of the first explosions, and sent aircraft to find the source. The battery was hidden in the forest of Courcy, an unimaginable 120 kilometres away, and Krupp’s long-range siege gun continued to shell the city until August, scattering some 20 shells across Paris each day. This new ‘fire on Paris’ killed 250 people and caused widespread damage, but had little effect on everyday life in the city.

Marie Harrison reported from Paris on 25 April 1918:

I was in Paris during the first days of the bombardment, and I know something about the morale of the city under circumstances of acute unpleasantness. Air raids are horrible enough but they have their time limit. There is no “all clear” in an attack by the mystery gun. I remember that on Good Friday it began early in the morning, and the explosions continued throughout the day, occurring precisely at every quarter of an hour. That is a form of irritation which the Huns thought would empty Paris in a week. Some people left the city as some people have left London to escape the raid. But the greater number of Parisians went quietly about their work and did not even leave the business at hand to seek shelter from the approach of the next expected attack. Paris is so close to the war and has lived for so long beneath its shadow that it would take more than a long range-gun to disturb the normal course of its way of living.

Ironically, at the start of the war the French high command – like the other belligerents – had believed that the primary role of its own air force would be reconnaissance, and aircraft were soon soon providing crucial intelligence to range field guns on the battlefield. Even when the French turned to tactical and strategic bombing, air power remained, as General Pétain insisted, ‘the direct extension of artillery’, so that all efforts had to ‘converge on the essential act: the battle’.

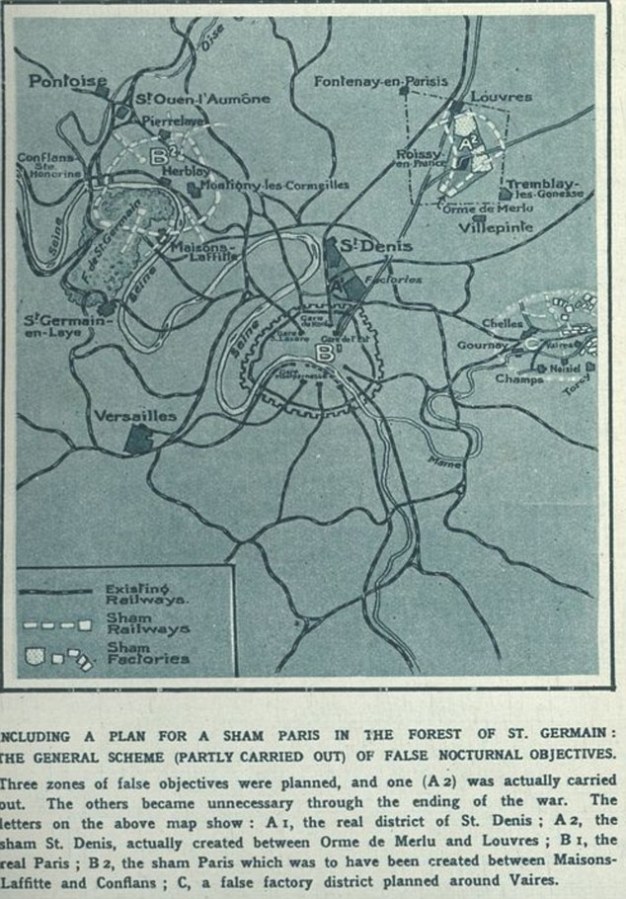

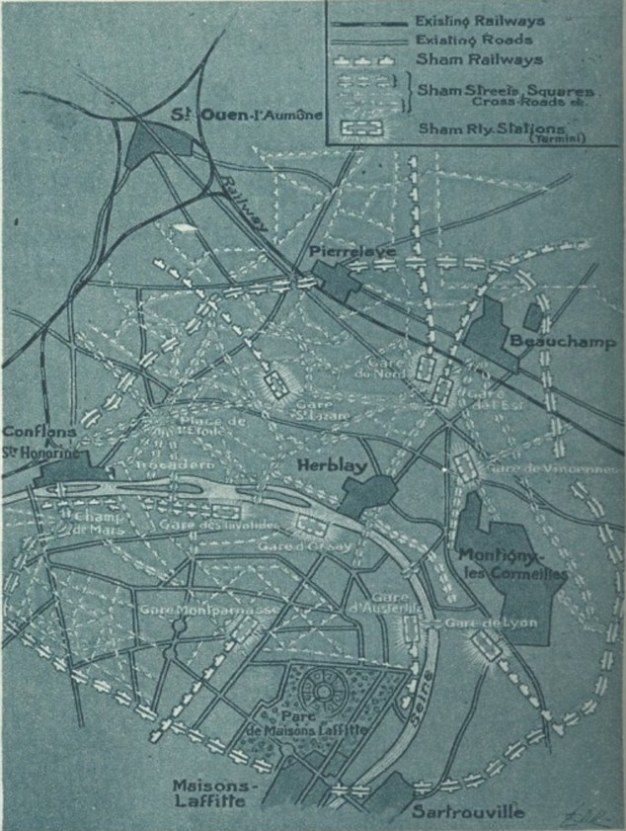

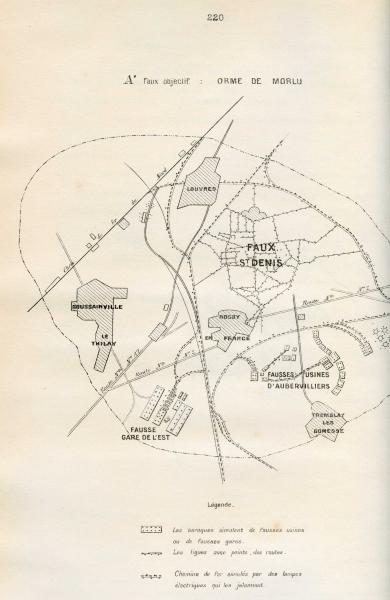

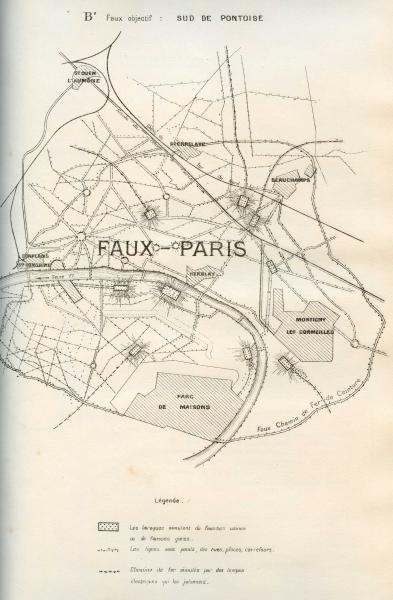

Still, the fear of escalation was real enough, and with the example of the dramatic increase in air raids on London before their eyes, in March 1918 the DCA started construction of a dispersed faux Paris on a great loop of the Seine north of the city (more here). Three separate sites were selected to draw German night-bombers away from the capital. Wooden buildings with canvas roofs were to be used to mimic glass-roofed factories, and the plans included a dummy Gare de l’Est and Champs-Elysées; the designers experimented with ‘all sorts of variations and colours of lights’ to convince German pilots that they were bombing Paris. The plans, largely unrealised, were revealed in a photo-essay in the Illustrated London News on 6 November 1920, which reported that this was ‘a “city” created to be bombarded.’

These sketches were drawn for the ILN but here are original maps from October 1918 of ‘objectif A’ and ‘objectif B’:

The danger was more imminent and more substantial than the DCA could have known. On the night of 23 September 1918 the last of 20,000 new, deadly incendiary bombs – ‘Elektrons’ – were being loaded on to 45 heavy Giant bombers for a devastating raid on Paris. The plan, according to Neil Hanson in First Blitz (Doubleday, 2008), pp. 330-333, was to create an immense firestorm. Some of the pilots had already completed their final checks before starting their engines. Suddenly a staff car raced across the airfield with orders from Ludendorff abruptly cancelling the mission. Whether this was the result of a fear of the reprisal raids that such a spectacular attack would provoke (a simultaneous raid was to be launched against London – the focus of Hanson’s book) or whether the high command had already realised they would have to sue for peace is unclear. What is certain is that Paris was saved at an eleventh hour 18 days before the final eleventh hour of the Armistice.

Postscript: Faux Paris remained largely a paper city, but in the not too distant future quite other ‘towns to be bombed’ would be built.

After the bombing of Coventry in 1940 Britain created a number of bombing decoys – known as Starfish sites (from SF: ‘Special Fires’) – to lure the Luftwaffe away from towns and other strategic locations. The first was on Black Down in Somerset’s Mendip Hills, where Shepperton Film Studios created a fake Bristol (of sorts), including ‘glow boxes’ designed to simulate the streets and marshalling yards and creosote and water ‘fires’ to simulate incendiary bombs. It was part of a dispersed system of sites standing for other parts of the city – for example, the docks and marshalling yards at Canon’s Marsh were reproduced at Burrington close by. For an RAF photograph of the Black Down site at night see here. By the end of the war there were over 200 sites protecting 80-odd locations, including London and Manchester. More here, and much more information in Colin Dobinson, Fields of deception: Britain’s bombing decoys of World War II (Methuen, 2000; a new edition is advertised for 2013).

After the bombing of Coventry in 1940 Britain created a number of bombing decoys – known as Starfish sites (from SF: ‘Special Fires’) – to lure the Luftwaffe away from towns and other strategic locations. The first was on Black Down in Somerset’s Mendip Hills, where Shepperton Film Studios created a fake Bristol (of sorts), including ‘glow boxes’ designed to simulate the streets and marshalling yards and creosote and water ‘fires’ to simulate incendiary bombs. It was part of a dispersed system of sites standing for other parts of the city – for example, the docks and marshalling yards at Canon’s Marsh were reproduced at Burrington close by. For an RAF photograph of the Black Down site at night see here. By the end of the war there were over 200 sites protecting 80-odd locations, including London and Manchester. More here, and much more information in Colin Dobinson, Fields of deception: Britain’s bombing decoys of World War II (Methuen, 2000; a new edition is advertised for 2013).

All of this intersects with a rich literature on camouflage – and in geography (and anywhere else, for that matter) I’m thinking of Isla Forsyth‘s marvellous work – but we should remember that other fake towns were built during the Second World War for entirely the reverse purpose: for experimenting with fire-bombing and, ultimately, for testing the atomic bomb.

Pingback: 8/3/1918 Bombing Paris, preparing for the spring offensive #1918Live | World War 1 Live

Pingback: Aerial violence and the death of the battlefield | geographical imaginations

Pingback: A happier new year | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Angry Eyes (1) | geographical imaginations

Is there any chance you could let me have the source of the image above showing the DCA Staff looking at a large map display or a good scan so that the captions can be read. I am currently researching for the RAF WWI air defence systems.

Much appreciated

Steve

Pingback: Countdown before midnight | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Dimanche 30 août 1914: Paris est bombardée pour la première fois

Pingback: 3-D War « geographical imaginations

Pingback: Over the top « geographical imaginations