I’m still in Beirut where I’ve had a wonderful time at the Transnational American Studies conference at AUB. Yesterday morning I chaired a panel on ‘Geographies of War‘, which featured Laleh Khalili (on Kuwait, military logistics and private contractors: abstract here), Lisa Hajjar (on the (il)legal strictures and injustices at Guantanamo; she changed her paper so I can’t link to an abstract), and Jeremy Scahill (‘The world is America’s battlefield’: abstract here).

In the evening Jeremy showed the film of Dirty Wars, co-written with David Riker and directed by Rick Rowley. Bear with me here; I’ll return to those ‘geographies’ in a moment. Seeing the film for a second time (the first was in Toronto in the fall with Jaimie and Jorge) I have to say I found it less satisfactory – I much prefer the book, but it’s not only because the written version is (inevitably) more detailed and more nuanced. I think it has something to do with the film being less an act of investigative journalism than a reconstruction of investigative journalism, a noir docudrama in which the investigator (no less inevitably) becomes the central figure: Sam Spade with a notebook. For that reason, I think Michael O’Sullivan is simply wrong to say that ‘the film is a documentary pure and simple.’

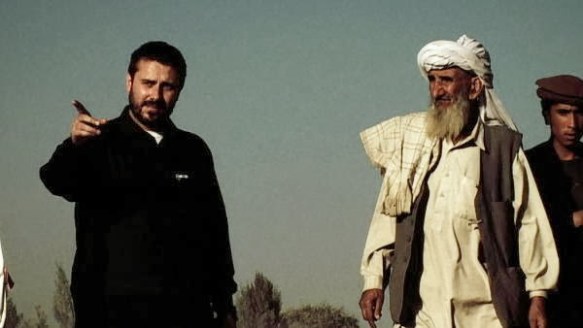

You can see that most obviously in the section that deals with a Special Forces night raid in February 2010 on a compound in Gardez, Afghanistan, where much of the ground-breaking reporting was done by another journalist, Jerome Starkey. But these scenes have incredible dramatic force, none the less, and the incorporation of cellphone footage of the raid and the unmasking of the Special Forces commander are genuinely and profoundly arresting (if only that were literally true).

I’m less convinced by the sections that treat the targeted killing of Anwar al-Awlaki, probably because I’m still dismayed that it was the killing of a U.S. citizen that sparked so much public outrage in the United States rather than the killing of all the others. Certainly in the film, far more so than the book, there’s an unwavering focus on the ‘Americanness’ of al-Awlaki, and especially of his transparently innocent teenage son, murdered by a drone strike just two weeks later. Home videos, games, clothes, a whole series of images are put to work to show not that ‘they’ are just like ‘us’ but that in some substantial sense ‘they’ are ‘us’. I was left wondering about those who don’t qualify for these sort of identifications, who can’t provide similarly legible identity papers: how are we to recognise and acknowledge their lives as grievable too? There’s also something unsettling about Jeremy’s epiphany that he’s come to Yemen ‘to apologise’: I’m still trying to figure out how he could, and what position he would have had to occupy for that to mean very much to al-Awlaki’s grandparents and cousins in Sa’ana.

Finally, the extended passage through a war-ravaged town in Somalia, crouching alongside militias and interviewing a warlord who gives very little away, seems to run into the sand. I was left with the uncomfortable feeling that these sequences had been retained primarily for Mohamed Afrah Qanyare‘s assertion (about his paymasters) that ‘America knows war… They are the war masters.’

Finally, the extended passage through a war-ravaged town in Somalia, crouching alongside militias and interviewing a warlord who gives very little away, seems to run into the sand. I was left with the uncomfortable feeling that these sequences had been retained primarily for Mohamed Afrah Qanyare‘s assertion (about his paymasters) that ‘America knows war… They are the war masters.’

And yet, of course, America doesn’t know war: Bush and Cheney famously avoided Vietnam, most of the war managers view the results of their military and paramilitary violence on screens and spreadsheets, and most of the public turns the other way. As Kamila Shamsie says in Burnt Shadows, the United States fights ‘more wars than anyone else; because you understand war least of all’ (see also my draft introduction to The everywhere war here; scroll down).

That’s precisely why investigative journalism and documentary films are so urgently necessary – and why we need these different forms – but I’m not sure that rendering Jeremy’s courageous and principled investigations in the black and white tones of a Hollywood thriller is the best way to bring ‘what is hidden in plain sight’ into public view. (For a different take, that pays close attention to the visual codes in the film, see Mike Hill‘s very smart essay over at Feedback here). I do know that films have to be different from books, that they have different grammars if you like, and I also understand that one of the most effective ways of soliciting an audience’s response is through story-telling – academic prose would be considerably less deadly if it had more narrative force – but in the end I’m with Roger Ebert:

‘Scahill is so respected and convincing that he doesn’t need such propping up, so the flashy directing and editing makes it feel as though “Dirty Wars” is trying too hard to sell things that might have sold themselves just fine without the hot box approach.’

Other (non-film) critics have objected to the way in which the history of clandestine/covert war is foreshortened in Dirty Wars, so that the CIA is left in the shadows. But that’s surely because in the wake of 9/11 the CIA was, in some crucial respects, pushed out of the limelight and a vastly aggrandised Joint Special Operations Command took centre stage to play for Cheney and Rumsfeld. And it’s the combination of a para-militarized CIA and JSOC that is instrumental in pushing the boundaries of the everywhere war.

- Red markers: U.S. Special Operations Forces deployment in 2013.

- Blue markers: U.S. Special Operations Forces working with/training/advising/conducting operations with indigenous troops in the U.S. or a third country during 2013.

- Purple markers: U.S. Special Operations Forces deployment in 2012.

- Yellow markers: U.S. Special Operations Forces working with/training/advising/conducting operations with indigenous troops in the U.S. or a third country during 2012.

US Special Operations Deployments, 2012-2013

While I was writing this, a new report from Nick Turse popped on to my screen, charting the extraordinary global geography of JSOC (above) and its entanglements with other militaries and agencies like USAID. JSOC has set up its own shadow system of subcommands mirroring the Pentagon’s division of the globe into unified combatant commands like US Central Command, each assigned to a different geographical region:

US Special Operations Command – Subcommands

I’ve taken the map above from US Special Operations Command’s own ‘Factbook‘, though it’s so reluctant to disclose any information that here too, as you’ll see if you read Nick’s article, part of the story is getting the story. If you read this alongside Steve Niva‘s brilliant essay, ‘Disappearing violence: JSOC and the Pentagon’s new cartography of networked warfare’, Security dialogue 44 (3) (2013) 185-202, and in conjunction with the gritty detail (and vivid prose) of Dirty Wars, you’ll have a desperately disturbing sense of one of the modalities that is producing these new geographies of war. As Scott Horton tells Jeremy in Dirty Wars, ‘suddenly the theatre of war has become the entire globe – it’s become everywhere.’

Pingback: More dirty dancing | geographical imaginations

Reblogged this on anatolikoblog.

Reblogged this on Oxtapus *beta.