Following up my post on The war on Ebola, Alex de Waal has a characteristically thoughtful essay over at the Boston Review on Militarizing global health:

This is worryingly authoritarian, bad for public health, and strategically counterproductive. Despite its impressive logistics, the army makes only a marginal contribution to international disaster relief — and often makes things worse. Nor do soldiers “fight” pathogens — and the language of warfare risks turning infected people and their caretakers into objects of fear and stigma.

Even brave and compassionate civilian fieldworkers are not immune from the military metaphors. Here, for example, is Sarah Crowe of UNICEF describing her work on the ‘frontline’ in Liberia’s ‘biological war’:

‘Ebola has turned survivors into human booby traps, unexploded ordnance – touch and you die. Ebola psychosis is paralysing…

‘In the car with colleagues, they talk almost nostalgically about the long civil war here – a time when the enemy was seen, the rockets were heard, the bullets could be dodged.’

If you want refuge from the paranoid hallucinations about the non-metaphorical weaponisation of Ebola by either the United States or ISIS read (respectively) Jim White here and Scott Stewart here.

Back to Alex, who provides a crucial and extremely helpful gloss on the recent history of US research on the intersections between epidemic disease and national security, which shows:

Modern epidemics do not cause security crises… Newly evolved pathogens are a constant threat, but a rerun of the near-total devastation of the native American populations by diseases entirely new to them is far-fetched for the simple reason that there are no longer any large populations wholly isolated from, and therefore at risk of, major infections. The greater dangers come from panicked or coercive responses to disease.

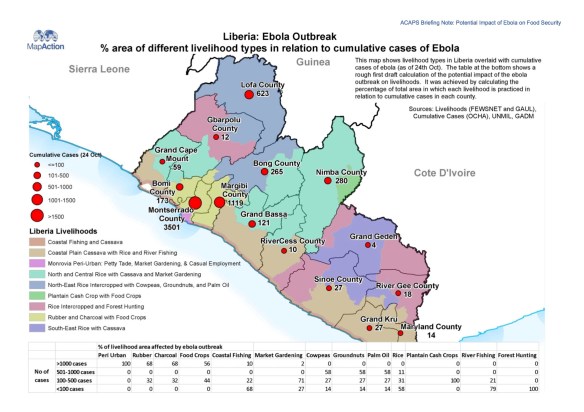

And for all the attempts to securitise Ebola, there has been remarkably little attention paid to its implications for food security (an altogether different problematic). Here the work of the Assessment Capacities Project (ACAPS), an initiative of Action Contre la Faim, the Norwegian Refugee Council and Save the Children International, is exemplary – see their detailed Briefing Note, Ebola in West Africa: potential impact on food security (10 November), from which I’ve taken the map below (there are others in the Note).

Alex points out another problem with the militarization of public health: ‘the legacy of colonialism and coercive medicine.’

Best practices in global health include efforts to be sensitive to national histories and cultures and to overcome the suspicions induced by outside health programs. Medicine in khaki is not only inefficient, it is bad practice.

British, French, and American armies have a history of imposing control in the name of hygiene, cordoning off a city or as-yet-insufficiently governed parts of the global borderlands…. In much of Africa, public health has struggled to free itself from the way it was implicated in coercive colonial control measures.

It is precisely this insight that eludes Tom Koch in his discussion of the history of mapping and containing epidemic disease in general and Ebola in particular. ‘It’s not “like” wartime,’ he proclaims: ‘It is war.’

To combat the expanding bacterium or an advancing, viral incursion has always required military style thinking. To survive, a microbe requires potential hosts who can be effected just as invading armies require supplies if they are to advance. To tame a microbial incursion requires containment procedures that will deny it new hosts, new supplies.

He is right to point to the strategic importance of mapping – on the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency’s public involvement, incidentally, see here – but maps (like metaphors) do more than describe, and depending on the web of practices and powers in which they are activated the connections between mapping and containment are in many cases performative. I’m surely not the only one to be reminded of Michel Foucault‘s illuminating discussion of the plague-stricken town: see also Stuart Elden‘s commentary on ‘Plague, Panopticon, Police’ here, which reinforces the suggestions I made about military/policing and quarantine in my original post. But this involves more then AFRICOM, and Donald McNeil‘s report on the decision to use local militaries to impose a cordon sanitaire in areas of Liberia and Sierre Leone (below) is also instructive – as he says, ‘a tactic unseen in a century’ and with ‘the potential to become brutal and inhumane’.

It may also backfire. Alex again (my emphases):

One of the great, under-recognized successes of the response to HIV and AIDS in Africa was that the spread of an incurable sexually transmitted infection did not lead to repressive measures or massive stigmatization. On the contrary, the United Nations and donors insisted that public health be linked to human rights, and civil society organizations and people living with HIV and AIDS be represented in the governance of UNAIDS and the Global Fund.

That is the polar opposite of the war-like approach to Ebola. The Sierra Leonean journalist Oswald Hanciles drew out the implications of Koroma’s “war” on Ebola, comparing it favorably with the weak government defenses against the rebel attacks fifteen years ago: “This strategy of energizing and mobilizing youth to ‘comb’ their neighborhoods to ferret out ‘Ebola suspects’ could be the most potent in this Ebola War. We are optimistic that the President would use the security forces to back up the youths who the President said should be ‘hard.’” That would be a frightening prospect. Vigilante mobs dragging people from their homes or sealing off neighborhoods would destroy the public trust and community involvement at the heart of good public health practice.

It’s not only vigilante mobs; the image below shows a Liberian soldier beating a local resident while enforcing a quarantine in Monrovia’s West Point slum:

And yet several loud voices doubt that local militaries, even acting in concert with AFRICOM, can provide a sufficiently powerful vector, and they want the militarised response to be stepped up. Earlier this month Britain’s former Chief of the Defence Staff joined calls for NATO to take command:

General Sir David Richards said that he was “strongly supportive” of a proposal for Nato to take command of the international response to West Africa’s Ebola outbreak, adding that the crisis demanded “a grand strategic response…

“What a crisis like this requires more than anything else is efficient organisation and leadership. It is quite clear that currently these vital ingredients are missing… The military’s core skills are to analyse a problem, devise a plan … and then to execute that plan under pressure.”

It may be that the ‘organisation and leadership’ they have in mind is a matter of logistics. The United Nations has a Global Logistics Cluster, whose ‘concept of operations’ is mapped below (see also its Regional Situation Report for 3-10 November here) , and Richards and his co-signatories make it plain that, in their view, the UN is ‘most unlikely to be up to the job’ – though they never clarify exactly what that ‘job’ might be and what they expect NATO to do. In any case, readers of Deb Cowen may well wonder about another dimension of what she calls ‘the deadly life of logistics’…

So I leave the last word to Alex:

The comparative advantage of the military lies in a few niche activities, such as airport infrastructure, transport helicopters, and — uniquely for this case — medical facilities to treat health workers when they themselves fall sick. All other activities are done far better by civilians.

Pingback: Covid-19 and armed conflict | geographical imaginations

Pingback: West Point and the war on Ebola | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Tomorrow’s Battlefield | geographical imaginations