Frédéric Mégret has frequently drawn attention to the peculiar social and legal status of the battlefield:

‘[W]hilst war may and will rage, what distinguishes it from random violence is the fact that it unfolds in discreet spaces insulated from the rest of society, confining military violence to a confrontation between specialized forces whose operation should minimally disrupt surrounding life…. In that respect, the laws of war do not merely seek to regulate the battlefield. They are also part of its symbolic maintenance and even construction as a particular space defined by the norms that apply to it. In other words, the battlefield does not predate norms on warfare; rather it has always been subtly coterminous with them. The laws of war are, therefore, a crucial foundation for understanding the evolution of the battlefield and, conversely, the evolution of the battlefield is a key way in which the evolution of the laws of war can be understood.’

For Mégret, the deconstruction of the battlefield is now well advanced: starting in the nineteenth century, with transformations in firepower that constantly extended the range over which lethal force could be deployed, dramatically accelerated with the rise of airpower annulling the distinction between the spaces of combatants and civilians, given a further twist by remote operations conducted over vast distances from unmanned aerial systems like the Predator and the Reaper, and aggravated by the renewed significance of insurgency and counter-insurgency struggles (‘war among the people’), the relations between the spatiality of war and its legal armature have been radically transformed. (For a visual rendering, see Mégret’s Prezi on ‘Where is the battlefield?’).

These are important ideas, but there are other dimensions that need to be taken into account when considering Israel’s latest attack on Gaza. This is a conflict that is fully coterminous with what Helga Tawil-Souri calls Israel’s ‘digital occupation’ of Gaza. As she writes in a superb essay in the Journal of Palestine Studies 41 (2) (2012) 27-43:

‘Disengagement has not meant the end of Israeli occupation. Rather, Israel’s balancing act “of maximum control and minimum responsibility” has meant that the occupation of Gaza has become increasingly technologized. Unmanned aerial reconnaissance and attack drones, remote-controlled machine guns, closed-circuit television, sonic imagery, gamma-radiation detectors, remote- controlled bulldozers and boats, electrified fences, among many other examples, are increasingly used for control and surveillance One way to conceptualize disengagement, then, is to recognize it as a moment marking Israel’s move from a traditional military occupation toward a high-tech one.

Rooted in Israel’s increasingly globalized security-military-high-tech industry, the technological sealing of Gaza is part of the transformation of the mechanics of Israeli occupation toward “frictionless” control that began with the first intifada and the ensuing “peace process,” which marked the shift toward the segregation of Gaza. “Frictionless” is, of course, metaphoric and purposefully ambiguous, evoking a sense of abstraction and lack of responsibility…

While high technology has become one of the means through which Israeli occupation continues, the high-tech infrastructure in the Gaza Strip — that which is used by Palestinians as opposed to the Israeli regime— is also a space of control. Technology infrastructures form part of the appa- ratus of Israeli control over Gazans. A telephone call made on a land-line, even between Gaza City and Khan Yunis, is physically routed through Israel. Internet traffic is routed through switches located outside the Gaza Strip. Even on the ubiquitous cellular phones, calls must touch the Israeli backbone at some point. Like much else about the Gaza Strip, telecommunication infrastructures are limited by Israeli policies. Geographic mobility, economic growth, political mobilization, and territory are contained, but so are digital flows: Gazans live under a regime of digital occupation.’

It should come as no surprise, therefore, that Israel also fights in digital space. This takes many forms, and at the limit extends into the domain of cyberwarfare (where, as the joint US/Israeli cyber-attack on Iran’s nuclear program showed, Israel possesses advanced capabilities), but in its more mundane version it can be no less effective.

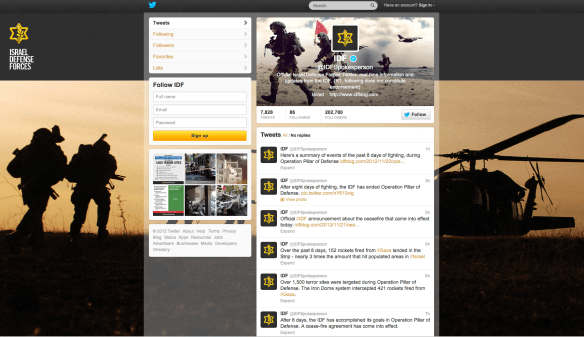

One of the characteristic features of late modern war is its mediatization, and the Israeli Defense Forces have used (even ‘weaponized‘) an array of social media platforms to shape the public construction of the battlespace. This is a far cry from its faltering efforts during the previous assault on Gaza in 2008-9, Operation Cast Lead. Soon after the IDF assassination that sparked the renewed air campaign this month, the IDF tweeted a headshot of the dead man, Hamas military commander Ahmed al-Jabari, with “eliminated” stamped across it, and immediately followed up with a video uploaded to its YouTube channel showing the drone strike (I’m not going to do the IDF’s job for it, but if you want to see stills and screenshots you can find them here). The IDF continued to tweet, announcing its airstrikes in 140-character containers, and also turned to Facebook, Pinterest and Tumblr to post images and infographics (or, more accurately, propagandagraphics).

The object of the exercise has been three-fold.

First, the IDF has been seeking direct – which is not to say unmediated: the clips, tweets and the rest follow an artfully pre-arranged script – and real-time access to domestic, regional and international publics. The officer commanding the IDF’s 30-strong New Media desk (which is shown in the image on the left), Lt. Col. Avital Leibovich, explained that she wanted ‘to convey our message without the touch of an editor’ and to reach those who don’t turn to print media or TV for their news.

First, the IDF has been seeking direct – which is not to say unmediated: the clips, tweets and the rest follow an artfully pre-arranged script – and real-time access to domestic, regional and international publics. The officer commanding the IDF’s 30-strong New Media desk (which is shown in the image on the left), Lt. Col. Avital Leibovich, explained that she wanted ‘to convey our message without the touch of an editor’ and to reach those who don’t turn to print media or TV for their news.

Second, the IDF has been aggressively mobilising its supporters, inside and outside Israel, encouraging them to retweet and to post their support on Facebook: using social media to puncture what Israel routinely describes as its ‘isolation’. Time reported that the IDF had activated additional ‘gamification’ features on its blog that allowed visitors ‘to rack up “points” for repeat visits or numerous tweets’: see the image on the right; more here.

Second, the IDF has been aggressively mobilising its supporters, inside and outside Israel, encouraging them to retweet and to post their support on Facebook: using social media to puncture what Israel routinely describes as its ‘isolation’. Time reported that the IDF had activated additional ‘gamification’ features on its blog that allowed visitors ‘to rack up “points” for repeat visits or numerous tweets’: see the image on the right; more here.

Third, the IDF apparently believes that social media can send ‘a message of deterrence’ – though its tweets have surely been as likely to provoke as to intimidate. The campaign sparked a series of responses and counter-measures – in Gaza, Hamas and its supporters, and in particular the Al-Qassam Brigades led by al-Jabari, took to social media platforms too, though Israel’s digital occupation plainly made that a vulnerable strategy, and the cyberactivist group Anonymous claimed to have defaced or disrupted nearly 700 Israeli political, military and commercial websites – so that al Jazeera described this as a ‘mass cyber-war‘ (I think that’s wrong: it’s been a social media war, but not one that has directly produced destruction – though, as I’ll suggest in a moment, it has certainly invited it).

More on the IDF’s New Media desk from Fast Company here and from the VJ Movement below:

It’s hard to know how effective this social media blitz has been: certainly, many people have been repulsed by the way the IDF ‘cheerily live-tweets infanticide’ and ‘the apparent glee with which the IDF carries out its job.’ As John Mitchell complained, ‘Innocent people are dying on all sides, and the IDF wants to reward people for tweeting about it.’ In doing so, the contemporary rendering of war as spectacle and entertainment has been turned into something at once banal and grotesque. Alex Kantrowitz put this well:

When a military at war asks its Twitter followers to “Please Retweet,” or check out its Tumblr, or posts an image of a rocket hooking a Prime Minister’s undergarments, it is hard not to sense a disconnect between that messaging and the bombing taking place in real life. As The Verge’s Joseph L. Flatley put it, “One liveblogs award shows or CES keynotes, not armed conflict.”

When Matt Buchanan calls this live-tweeting of military and paramilitary violence ‘the most meaningful change in our consumption of war in over 20 years’ – my emphasis – then this is war reduced to consumerism: how long before military commanders start worrying that if their ratings aren’t high enough, their audience penetration too low, their war will be cancelled? (Not such a bad idea, you might think, until they are driven to find ways to increase their market share….) Buchanan may think this is ‘How to Wage War on the Internet’, but Michael Koplow is nearer the mark: it’s precisely How Not to Wage War on the Internet.

In fact, several commentators worry that the trash-talking between the two sides, the verbal violence of response and counter-response on Twitter, was an open invitation to extend the war beyond the words:

‘This is a new reality of war,’ Heather Hurlburt noted, ‘and I worry that it’s going to make it harder to stand down.’ The digital exchanges were immediate – not the language of reflection or diplomacy – and, whatever else they were about, were clearly intended to taunt the other side: Hamas and the IDF were both targeting audiences in Gaza (and the West Bank) and in Israel, by turns rallying their supporters and goading the enemy. In short, here as elsewhere, there are crucial connections between the physical and virtual worlds that, in this case, may work to inflame the violence.

Yet for all this the digital battlespace can work to reinstate the traditional battlefield – at least virtually and rhetorically. This is one of the maps circulated through the IDF’s social media platforms:

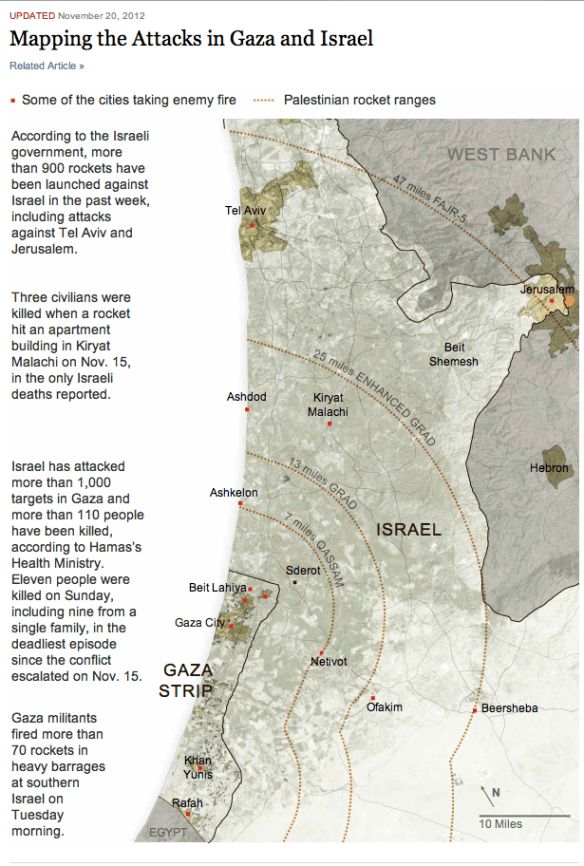

And here is the equivalent map published online by the New York Times, updated yesterday:

Here the map speaks power to truth: the ‘battlefield’ has been radically extended so that, as always, the terms of an an intensely asymmetric struggle are radically reversed. The disproportionate concentration of Israeli firepower on Gaza is erased, while virtually all of Israel – including, as we have been endlessly reminded, for the very first time Jerusalem – is threatened by Hamas.

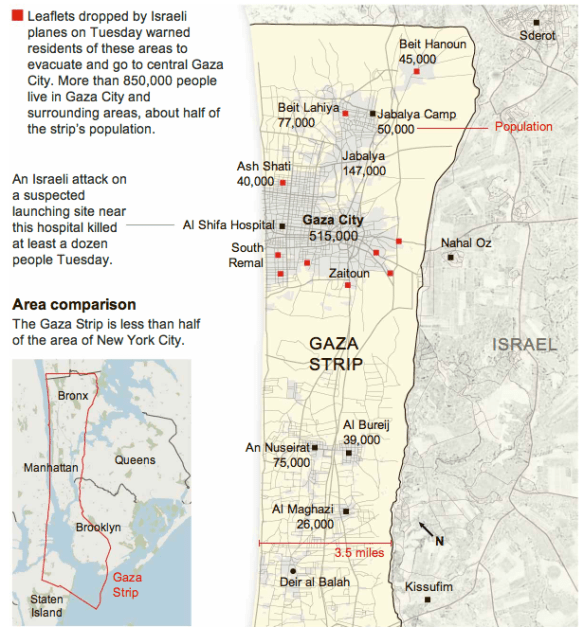

The Times did at least include this, separate map of Gaza:

The map plots (in red) the sites of IDF leaflet drops (really). So we have one map showing Hamas rocket ranges and ‘cities taking enemy fire’, and the other showing paper dropped on a captive population…

UPDATE: More on this from Craig Jones here.

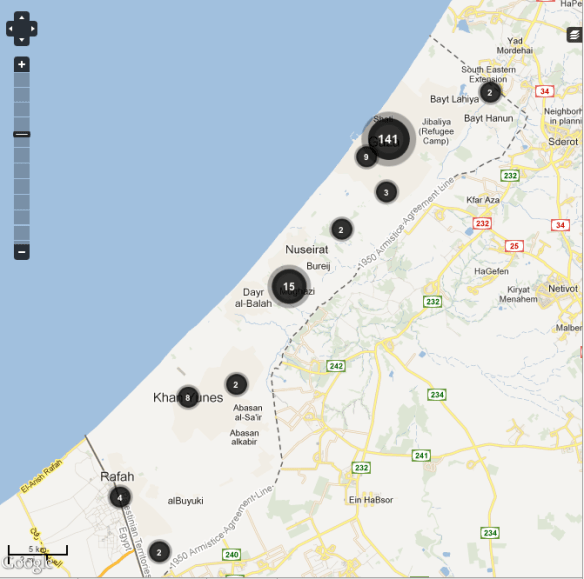

If you want to find more meaningful maps that take in both Israel and Gaza, including air strikes and rocket attacks, deaths and casualties on both sides, you can find them at al Jazeera here. I’ve pasted an extract from the plot of air strikes below.

Seen like this, I’ll leave the last words to Helga Tawil-Souri:

“The underlying reasons of Israel’s propaganda are to silence the enemy, gain international support and justify wars… Their goal has not fundamentally changed over the years, only the platforms on which these are disseminated.”

Pingback: Spaces of exception and enemies | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Still reaching from the skies… | geographical imaginations

Pingback: War against the people | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Inhumanitarian mapping | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Virtual Gaza | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Problematizing Cyber-Wars | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Gaza, stripped: the deconstruction of the battlefield? | The Vast and The Intricate

Pingback: Operation Exposure | War, Law & Space

Pingback: Death, drones and Camp Delta | geographical imaginations

Pingback: New paper: travelling law (and travelling theory) | War, Law & Space

Pingback: The individuation of warfare? | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Dirty dancing and spaces of exception in Pakistan | geographical imaginations

Pingback: The twitter of drones « geographical imaginations

Pingback: Mapping the 2012 Gaza attacks | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Just looking (and shooting) « geographical imaginations

Pingback: Saving Face(book) « geographical imaginations

Pingback: Media blitz « geographical imaginations

Pingback: Today’s read | War, Law & Space

Pingback: Gaza, stripped: the deconstruction of the battlefield? | Vengallez's Blog

Reblogged this on Experimental Geographies and commented:

Derek Gregory on Gaza and the ongoing deconstruction of the battlefield.

Pingback: On blogging and more… | Andy Davies's Blog

great piece Derek!