I’m in Cologne for the International Geographical Congress. It’s my second visit to the city – I’m on the international Scientific Committee involved in organising the IGC so I was here last year – but coming out of the main station and immediately seeing the vast cathedral again sends shivers up my spine. This was the aiming point for Bomber Command’s first ‘Thousand Bomber’ raid (“Operation Millennium”) on the night of 30 May 1942; ironically the cathedral survived, but the bomb load, fanning out in a triangle, fell across the most densely populated part of the city. One pilot compared the attack to ‘rush-hour in a three-dimensional circus’: 1,455 tons of bombs (high explosive and incendiaries) were dropped on the city in just ninety minutes, creating raging infernos that devastated 600 acres. The original target was Hamburg – attacked in July in “Operation Gomorrah” – but bad weather forced Bomber Command to switch the attack to Cologne (the nearest large city to Bomber Command’s bases). By the end of the war the RAF had dropped 23,349 tons of bombs on the city and the US Eighth Air Force 15,165 tons, and according to Jörg Friedrich 20,000 people had been killed in the attacks.

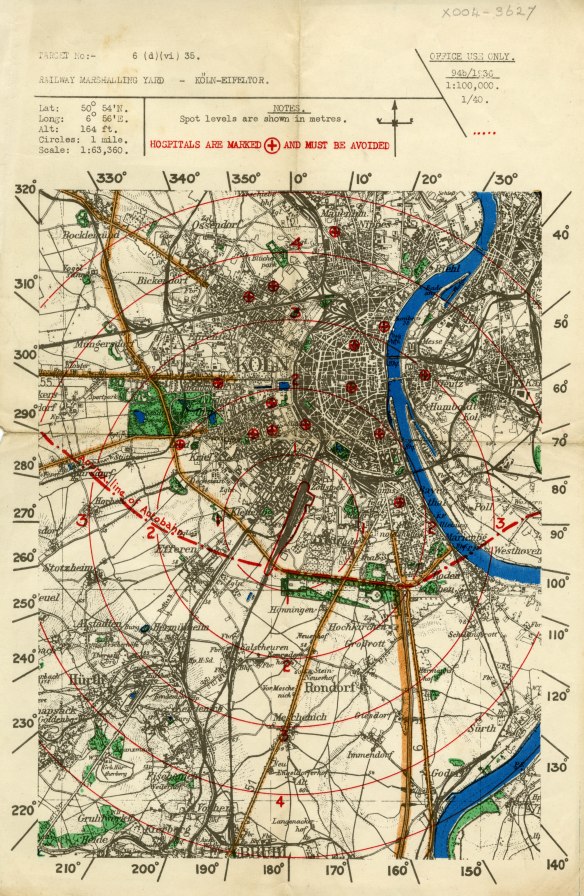

I’ve described the production of a city as a target in “Doors into nowhere” (see DOWNLOADS), and here is an early target map for Cologne; later ones were much more schematic since the detail was useless for night bombing or ‘blind bombing’ (‘bombing through cloud’) that were the characteristic modes of Bomber Command’s area bombing strategy.

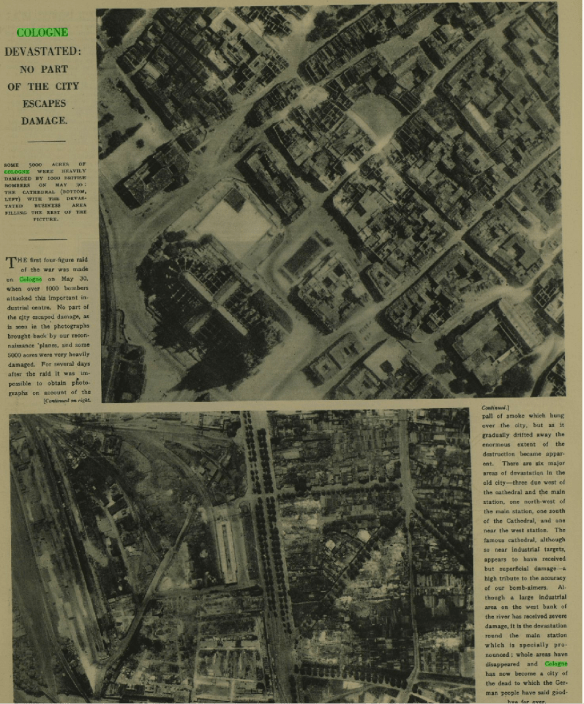

Operation Millennium gave Bomber Command a fillip, and the British press was ecstatic. Thrilled at ‘the most gigantic air raid the world has ever seen’, the Daily Express reported that one pilot had said ‘It was almost too gigantic to be real…’ The Times noted that it was the 107th raid on the city and that, as far as the eye could see, the sky was filled with aircraft, ‘waiting their turn in the queue’ and arriving over the target one every six seconds: ‘from the point of view of the attackers it was the perfect raid’. The News of the World had been shown daylight photographs of the aftermath: ‘No part of the city escaped, and the heavily-damaged areas total some 5,000 acres equal to an area of nearly eight square miles. The old town has gone. In addition to isolated points of damage, there are several major areas of devastation – due west of the cathedral and the main station; north-west of the main station; south of the cathedral; and near the west station.’ The language was abstract, one of lines and areas, because the ‘point of view’ was, like that of the aircrews who had carried out the attack, distant, and this geometric imaginary was confirmed when the photographs were published in the Illustrated London News:

Soon carefully edited cinema newsreels chimed in; at one briefing caught by the camera Cologne was hailed as ‘an old friend to many of you’, and the commentator described ‘tons and tons of beautiful bombs’ being loaded into the aircraft:

After the war, when British and American reporters could inspect the ruins of the city on the ground, they were stunned at the scale of destruction. Now the solid geometries of the city that they diagrammed were no longer clinical descriptions but chilling memorials. Janet Flanner [‘Genêt’], in her “Letter from Cologne” published in the New Yorker on 19 March 1945, described the city as ‘a model of destruction’, lying ‘shapeless in the rubble’: ‘Our Army captured some splendid colored Stadpläne, or city maps, of Cologne, but unfortunately the streets they indicate are often no longer there.’ (She wasn’t greatly impressed by the survival of the cathedral – its Gothic nave ‘was finished in exactly 1880’ – and thought ‘the really great loss’ was Cologne’s 12 eleventh-century Romanesque churches).

Sidney Olson cabled LIFE magazine in March:

‘The first impression was that of silence and emptiness. When we stopped the jeep you heard nothing, you saw no movement down the great deserted avenues lined with empty white boxes. We looked vainly for people. In a city of 700,000 none now seemed alive. But there were people, perhaps some 120,000 of them. They had gone underground. They live and work in a long series of cellars, “mouseholes”, cut from one house to the next.’

Alan Moorehead was was shaken to the core:

‘… few people I think were prepared for Cologne. There was something awesome about the ruins of Cologne, something the mind was unwilling to grasp, and the cathedral spires still soaring miraculously to the sky only made the débacle below more difficult to accept and comprehend… A city is a plan on a map, and here, over a great area, there was no plan. A city means movement and noise and people: not silence and emptiness and stillness, a kind of cemetery stillness. A city is life, and when you find instead the negation of life the effect is redoubled. My friends who travelled with me knew Cologne, but not this Cologne…[T]hey found themselves looking at disordered rocks, and presently they abandoned any attempt to guide our way by their memory of the city, and instead everyone fixed his eyes on the cathedral and used that only landmark as a guide across the rubble…’

Here is a compilation of contemporary film coverage, which includes Moorehead’s commentary:

Solly Zuckerman, a British scientist who had been closely involved in planning the bombing campaign, arrived early the next month and was so overwhelmed by what he saw that he found it impossible to write an essay he had promised Cyril Connolly’s Horizon: it was to be called “The natural history of destruction”. It was left to W.G. Sebald to redeem that promise, in his own way, many years later. But when he asked Zuckerman about his experience (their paths crossed at the University of East Anglia), all he could remember was a surreal still life: ‘the image of the blackened cathedral rising from the stony desert around it, and the memory of a severed finger that he had found on a heap of rubble.’

All this explains why the spectre of the cathedral – still blackened, rising today out of a grey and greasy wet sky – haunts me too.

Pingback: Remote sensing | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Deadly Embrace: the sawn-off version | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Seen/seduced from above « geographical imaginations

Pingback: The politics of drone wars « geographical imaginations

Pingback: Living (and dying) under drones « geographical imaginations