Here’s a selection of recent reports on drone strikes from around the web plus commentary:

Craig Whitlock completes the Washington Post‘s three-part series on ‘Permanent War’ – started by Greg Miller‘s report on the US ‘disposition matrix‘ for targeted killing – with a remarkable account of what he calls ‘the US military’s first permanent drone war base’ at Camp Lemonnier, just (barely) outside Djibouti City. It’s ‘the busiest Predator drone base outside the Afghan war zone’, from which Predators are launched around the clock, sixteen times a day, to conduct missions in Somalia and Yemen. Nominally overseen by US Africa Command (AFRICOM) – ‘the primary base of operations for US Africa Command in the Horn of Africa‘ – Whitlock mades it clear that it’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) that calls the shots. What is remarkable about Whitlock’s report is his artful piecing together of a jigsaw of information from construction solicitations, contracts and plans, submissions to Congress, planning memoranda, Air Force journals, and Predator accident investigation reports, some in the public domain and countless others obtained through FOI requests. More on drone wars in East Africa from Somalia Report (which also provided the image of Camp Lemonnier below) and on what David Axe calls ‘America’s secret drone war in Africa’ from Wired‘s Danger Room.

Alex Kane at Mondoweiss reprises the Columbia report on Counting Drone Strike Deaths issued earlier this month – which is sharply critical of the estimates of civilian casualties in Pakistan reported by both the New America Foundation and the Long War Journal and endorses those provided by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism – and then follows up with an interview with Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and the Associate Director of the Counter-terrorism and Human Rights Project at Columbia:

… all of these estimates, including our estimate, are just based on news reports, news reports filed in that region where journalists have very limited access to the scene of the crime, if you will.

It’s not like journalists, for the most part, are going to where the drone strike happened and talking to witnesses, doing a bit of, almost a forensic analysis, being able to see what happened with their own eyes. This [Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas] is a region where few journalists, even Pakistani journalists, can really get there. We’re talking about media reports that are often based on the word of anonymous, Pakistani government officials who have an interest in telling a story of, “drone strikes kill only militants.” We’re not going to see anonymous government officials admitting that many of the people killed are civilians. So it’s a stacked deck.’

All true. But there is a striking geographical absence from the kerfuffle over civilian casualties caused by drone strikes: Afghanistan. The situation there is no less fraught: as the map below shows, journalists in Afghanistan also work in highly dangerous circumstances. (More on the map here and more from the Committee to Protect Journalists here).

The politico-technical matrix is also more complicated: in Afghanistan Predators and Reapers are part of an extended network in which aircraft are linked to ground forces and through which remote operators carry out persistent surveillance while, on occasion, leaving attacks to conventional strike aircraft (though they certainly also launch them from their own platforms too). This makes it more difficult to disentangle drones from the wider apparatus of military violence – but why on earth should they be? Afghanistan is part of a recognised ‘war zone’ – but does that make civilian casualties there any less grievable than those that take place across the border?

In the Mondoweiss interview Shah draws attention to the perpetual fear induced by the persistent presence of the drones:

We’re talking about planes hovering over head for hours every single day, and really the casualty of that, the human casualty, is peace of mind for the people who live there. We see reports that parents don’t want to send their kids out to school, that people don’t know what’s going to get them killed by a drone strike. Imagine living in that kind of fear, and we’re talking about communities that are already ravaged by war.

For more on this, turn to UK-based Medact’s report on Drones: the physical and psychological implications of a global theatre of war, also issued earlier this month. Free download here.

For more on this, turn to UK-based Medact’s report on Drones: the physical and psychological implications of a global theatre of war, also issued earlier this month. Free download here.

Women are disproportionately affected by drones. What little control they have over their lives is further eroded by a weapon they know could strike at any time. Their lives and those of the children they try to protect are under constant threat. While men can sublimate their grief and anger to some degree by becoming fighters – one of the terrible consequences of drone warfare – women have no such outlet. And if their menfolk are killed in a drone strike, they may have to endure the continuing presence of the drone just overhead.

The report is a survey of surveys, short and to the point, but it adds a British dimension to the debate – important at a time when the RAF is doubling its Reaper fleet and moving control from Creech AFB in Nevada to RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire – and too briefly brings Israel’s use of drones in Gaza into the general discussion. That last point desperately needs to be sharpened, given the global prominence of the Israeli drone industry and the filiations between US and Israeli practices of targeted killing. Another depressing blank on the drone debate map.

(I hadn’t heard of Medact before, but it claims to speak out ‘for countless people across the globe whose health, wellbeing and access to proper health care are severely compromised by the effects of war, poverty and environmental damage’, and it’s associated with the journal Medicine, conflict and survival – a source which deserves close attention).

Haymarket Books has just published (pb and e-book versions) a collection of Nick Turse‘s columns on drones and Obama’s other signature modes of warfare, The changing face of empire: see here for an adapted version of the conclusion (extract below) and here for the book.

Haymarket Books has just published (pb and e-book versions) a collection of Nick Turse‘s columns on drones and Obama’s other signature modes of warfare, The changing face of empire: see here for an adapted version of the conclusion (extract below) and here for the book.

Several times this year, [General Martin Dempsey], the other joint chiefs, and regional war-fighting commanders have assembled at the Marine Corps Base in Quantico to conduct a futuristic war-game-meets-academic-seminar about the needs of the military in 2017. There, a giant map of the world, larger than a basketball court, was laid out so the Pentagon’s top brass could shuffle around the planet — provided they wore those scuff-preventing shoe covers — as they thought about “potential U.S. national military vulnerabilities in future conflicts” (so one participant told the New York Times). The sight of those generals with the world underfoot was a fitting image for Washington’s military ambitions, its penchant for foreign interventions, and its contempt for (non-U.S.) borders and national sovereignty.

And lastly, on an almost lighter note, Teo Ballvé at Territorial Masquerades has an artful post on ‘Writing like a drone’. Following up on the ‘New Aesthetic‘, he describes a robotic graffiti writer that can write text massages ‘on such high risk/high profile targets as the U.S. Capitol Building’ and ‘can be deployed in any highly controlled space or public event from a remote location.’ It’s the remoteness that presumably prompts Teo to call this a ‘graffiti drone’, but there are two other (remote) connections to the real thing.

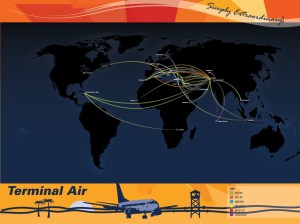

The project comes from the Institute for Applied Autonomy, which also hosts Trevor Paglen‘s captivating (sic) Terminal Air, a satirical version of the CIA’s extraordinary rendition flights – the ‘capture’ side of the kill/capture regime that uses drones for the ‘kill’.

Former US Ambassador Kurt Volker adds a gloss to this in an Op-Ed in the Washington Post following up the ‘Permanent War’ reports:

More people have been killed in U.S. drone attacks than were ever incarcerated at Guantanamo Bay. Can we be certain there were no cases of mistaken identity or innocent deaths? Those detained at Guantanamo at least had a chance to establish their identities, to be reviewed by an oversight panel and, in most cases, to be released. Those who remain at Guantanamo have been vetted and will ultimately face some form of legal proceeding. Those killed in drone strikes, whoever they were, are gone. Period.

What he doesn’t quite say is that most of those incarcerated at Guantanamo were, on the US government’s own admission, never al Qaeda fighters. More on the implications of these intelligence failures for the US targeted killing programme from the Stanford/NYU report on Living under drones here (scroll down).

Finally, back to Theo’s ‘graffiti drone’: one of several synonyms for graffiti writing – particularly at night – is bombing…

Pingback: Tortured geographies | geographical imaginations