When I wrote ‘The Black Flag’ (DOWNLOADS tab), exploring the idea of Guantanamo Bay as a space of exception, three young men had just committed suicide in the war prison. This is how I started:

In the early morning of 10 June 2006 three prisoners held at the military detention facility at the US Naval Station at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, two from Saudi Arabia and one from Yemen, were found dead in their cells. Although the three men had been detained without trial for several years and none of them had court cases or military commissions pending (none of them had even been charged), the commander of the prison dismissed their suicides as ‘not an act of desperation but an act of asymmetric warfare against us’. Although the three men had been on repeated hunger strikes which ended when they were strapped into restraint chairs and force- fed by nasal tubes, the US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy described their deaths as ‘a Public Relations move to draw attention’ – to what, she did not say – and complained that since detainees had access to lawyers, received mail and had the ability to write to families, ‘it was hard to see why the men had not protested about their situation’. Although by presidential decree prisoners at Guantánamo are subject to indefinite detention and coercive interrogation while they are alive, when President George W. Bush learned of the three deaths he reportedly stressed the importance of treating their dead bodies ‘in a humane and culturally sensitive manner’.

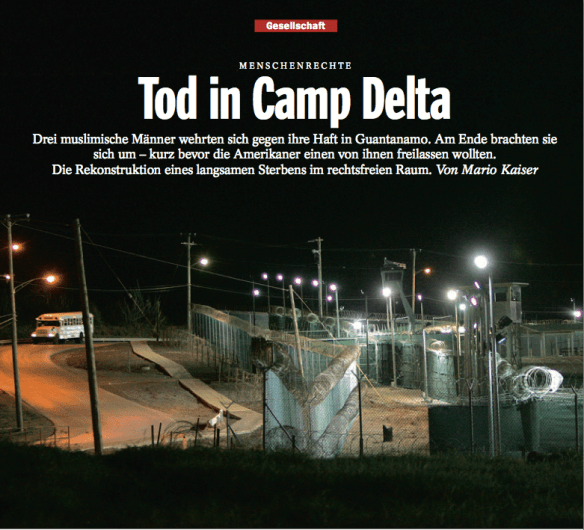

After ‘The Black Flag’ was published, I read a remarkable account of the despair and desperation of these three men by Mario Kaiser. His original essay has now been updated and translated into English as ‘Death in Camp Delta‘ at Guernica. Here is an extract:

At some point during their captivity, these three men began to retreat. They no longer touched the food the guards pushed through the holes in the doors of their cells. Their bodies dwindled. Their lives hung on thin yellow tubes shoved down their nostrils each morning to let a nutrient fluid drip into their stomachs. In their minds, nothing changed. They didn’t want to stay, and one night, on June 9, 2006, they decided to leave Guantánamo. They climbed on top of the sinks in their cells and hanged themselves.

In the Pentagon’s view, the men hanging from the walls of their cells were assassins whose suicides were attacks on America. The Pentagon struck back.

The story of the lives and deaths of these prisoners is an odyssey of three young men who left for Afghanistan and ended up in Cuba. It is the story of a war against a terror that is difficult to define, a war that the United States government wages even in the cells of its prisoners. It is about a place, Camp Delta, that exposes the asymmetry of this war, and it leads to the front lines—and the American lawyers standing between them, struggling to defend presumed enemies of their country. It is the story of the internal and external battle over Guantánamo.

Nobody but the dead knows the whole truth. But there are places where the story can be pieced together. There are files and letters, people who distinctly remember these prisoners. There are places where the strands of this story intersect. A law firm in Washington. A mosque in London. A living room in North Carolina. A cell in Guantánamo.

This is on my mind today for three reasons. The first is that Kaiser describes himself as

‘a writer who combines in-depth reporting with literary storytelling. Taking on issues of social transformation and human rights, Kaiser’s stories are based on long-term immersion in environments that are difficult to access. His hope is that this approach provides a fuller understanding of the ways in which policies and social change affect people’s lives and long-term prospects.’

It’s worth reflecting on those aspirations if you read his essay (which I urge you to do) because they raise important questions about the lazy distinction between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’, and about the ability of researchers to produce and animate publics through their (our) work. There’s something there, too, about the power (and, yes, the seductions) of story-telling: so much academic writing still seems to substitute and so privilege our own narrative (‘I did this… then I did that .. I thought this…. then I felt that’) for the stories of others. And, as Kaiser shows in that brief extract, those stories are often multi-sited.

The second reason Kaiser’s work matters to me is that I’m revisiting ‘The Black Flag’ for The everywhere war (more on this later) and, partly in consequence, thinking again about spaces of exception. I’m in Mexico this week, and I’ve been re-reading Giorgio Agamben‘s Homo sacer and The state of exception. I was originally doing this to sharpen my arguments about the Federally Administered Tribal Areas as a space of exception for air strikes by the CIA/JSOC and the Pakistan Air Force – I’ll be talking about this in Glasgow early next month, and I’ll post the presentation slides as soon as I’ve finished – but as I’ve worked my way through these texts still wider issues have emerged.

The second reason Kaiser’s work matters to me is that I’m revisiting ‘The Black Flag’ for The everywhere war (more on this later) and, partly in consequence, thinking again about spaces of exception. I’m in Mexico this week, and I’ve been re-reading Giorgio Agamben‘s Homo sacer and The state of exception. I was originally doing this to sharpen my arguments about the Federally Administered Tribal Areas as a space of exception for air strikes by the CIA/JSOC and the Pakistan Air Force – I’ll be talking about this in Glasgow early next month, and I’ll post the presentation slides as soon as I’ve finished – but as I’ve worked my way through these texts still wider issues have emerged.

One of the central elements of Homo sacer (and Remnants of Auschwitz – though here too the differences between the two texts are suggestive) is the deliberate exposure of bodies to death: outcasts from whom the protections of the law have been stripped so that their death is no crime. But in The state of exception Agamben’s focus is on the genealogy of the ‘force of law’ through which this takes place: the victims are nowhere in sight. Throughout the short text Agamben makes much of the proximity of war and, for the ’emergency’ that activates the modern state of exception, of the First World War, but war and its developing armature of (international) law is never subjected to critical scrutiny.

Yet war (and its casualties) can reveal something else about spaces of exception. On the battlefield – and let us immediately agree with Frédéric Mégret that ‘the battlefield’ is a highly unstable conceptual constellation – soldiers are at once vectors and victims of violence. Here the usual restrictions on killing are removed; they can kill, provided they do so ‘lawfully’, without risk of punishment (‘combatant immunity’). The other side of the contract, of course, is that those who might kill them are not subject to legal sanction either.

This is not what Agamben means by the state of exception, and apart from repeated references to a contemporary ‘global civil war’ (and to Guantanamo) the transnational rarely appears in his writing and international law disappears into the margins. His thumb-nail history of the state of exception is framed by the state and its sovereign.

But for reasons that I’ll set out in a later post, the proximity of the exceptional space of the ‘battlefield’, of war zones and killing fields, to the ultimate reductions of bare life, is far from accidental. In fact, that’s one of the links between the three deaths in Guantanamo Bay and air strikes and targeted killings in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan which, as I’ll want to show, requires a radically enlarged view of spaces of exception and their historical geographies. (In the case of the FATA, the Obama administration insists it requires a radically enlarged juridical conception of the ‘battlefield’ in time and space too).

To be continued.