In my analysis of CIA-directed drone strikes in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (see ‘Dirty Dancing’: DOWNLOADS tab) I drew upon the tabulations provided by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Chris Herwig‘s cartographic animation of casualties between 2004 and 2013: see my discussion here and the maps here.

Quartz’s CityLab is now running a week-long series on Borders (‘stories about places on the edge’) and it includes a new series of interactive maps showing civilian casualties from drone strikes in the FATA (this series also ends in 2013). Here’s a screenshot:

There’s not much geographical analysis – apart from noting the focus on North and South Waziristan – and, as I argued before, I think it a mistake to isolate drone strikes from the wider matrix of military and paramilitary violence in the borderlands (including air strikes by the Pakistan Air Force). And there are obvious problems in disentangling civilian casualties – the US Air Force has the greatest difficulty in identifying civilians in the first place.

It’s difficult to put all this together – and particularly to hear the voices of those caught up in a matrix of such extensive violence that, as Madiha Tahir puts it so well, ‘war has lacerated the land into stillness.’ In an exquisite essay in Public Culture 29 (1) (2017) Madiha reflects on that difficulty and the ‘spatial stories’ local people struggle to tell. Her title – ‘The ground was always in play’ – is borrowed from Michael Herr‘s despatches from Vietnam, but the full quotation explains how aerial violence echoes across this shattered land:

‘The ground was always in play, always being swept. Under the ground was his, above it was ours. We had the air.’

But the ‘we’ in the FATA is plural – a product of the ‘dirty dancing’ between Washington and Islamabad – and so we come to the story Madiha pieces together:

The story Mir Azad came to tell is this [and, as Madiha shows, he had travelled 500 difficult miles across South and North Waziristan to tell it]. In July 2015, American drones bombed and killed two of his cousins, Gul Rehman Khan and Mohammad Khandan. After Zarb-e-Azb began in June 2014, thousands of Waziris fled in all directions, businesspeople, farmers, militants, and students, including to the Pakistani villages in Barmal, and there the drones followed. The military operation and the “surgical” operation, carpet bombing and “precision strikes,” coordinated maybe, intentionally or not, they worked together to redraw the lines of movement, new containment zones, a shockwave that could start with ground troops in North Waziristan and end with a drone bombing a car in Barmal [in Paktika province, on the border with North Waziristan].

My extract can’t do justice to the essay: do read it if you can.

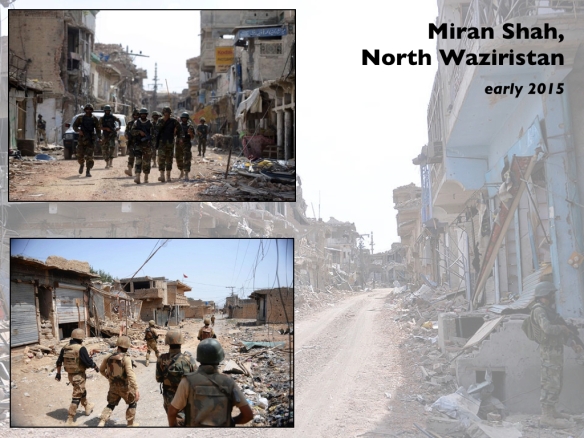

Since I completed the original version of ‘Dirty Dancing’ a number of new reports from Waziristan have provided more details of the co-ordination of air/ground operations. Over the summer AFP reported that the Pakistani military had removed the roofs of houses to provide a better ‘aerial view’:

“(The) military has removed the roofs of the houses to have a better aerial view and stop militants taking refuge in these abundant, fort-like mud houses,” the official told reporters. From the helicopter journalists could see scores of homes with no roofs but appearing otherwise intact, their interiors exposed to the elements.

But in many cases – especially in North Waziristan – those ordered by the military to leave their homes have returned to find them reduced to rubble.

Earlier this month Ihsan Dawar reported from North Waziristan on ‘Life on the debris of wrecked houses’:

Murtaza Dawar sat with his children and cousins on the debris of his house. Behind him the setting sun was a ball of fire in the sky, reducing him and his family to silhouettes, the shards of glass in the wreck of his house catching the light and winking in the gathering dark of an early evening.

Coming back home to Mirali in North Waziristan has been a bittersweet experience for Dawar, 48. Sweet because he and his family has returned home after more than two years of displacement. Bitter, because they have come back to wreckage where their home was.

“We have nothing to do with militancy or Talibanization but our house has been demolished,” says Dawar, taking a break from pitching a tent. “There is not a single room intact. I don’t know where to take my family to protect them from the terrible cold.”

Dawar’s is not the only house that was razed during the military operation Zarb-e-Azb, launched in June 2014 to clear North Wazristan of militants. Of the nearly million tribesmen displaced by the operation, many have lost not only their belongings and assets they left behind in the tribal district and their houses have been demolished for no reason.

The government has not issued any clear data on the number of houses demolished in North Waziristan. In May 2016, a property damage survey conducted by the Fata Disaster Management Authority (FDMA) revealed that 11,663 houses were fully and partially damaged during operations against militants in South Waziristan, North Waziristan and the Khyber Agency.

Local tribesmen working in the political administration’s office in North Waziristan told Truth tracker on condition of anonymity – because of the sensitivity of information – that about 1500 houses were completely destroyed in the Mirali subdivision alone.

Cartographic animations can’t capture these in-animations, but we must surely do our best to attend to them.