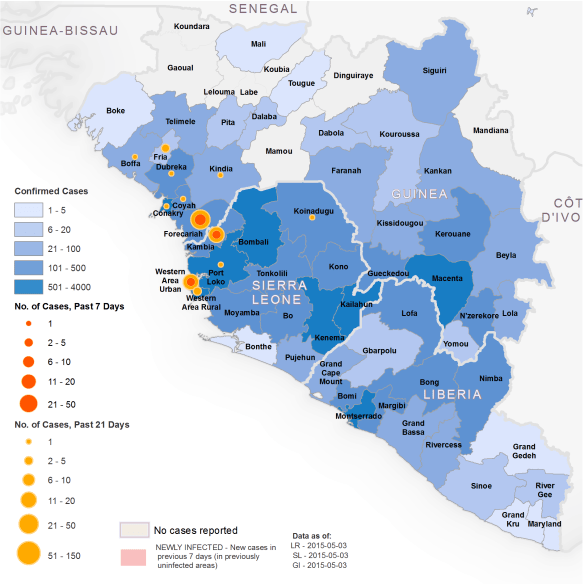

I’ve taken this map from a Situation Report issued by the World Health Organisation on 6 May, which superimposes new cases of Ebola virus disease (EVD) over total confirmed cases throughout the epidemic in West Africa:

Three days later the WHO declared Liberia to be free of Ebola:

Forty-two days have passed since the last laboratory-confirmed case was buried on 28 March 2015. The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Liberia is over.

Interruption of transmission is a monumental achievement for a country that reported the highest number of deaths in the largest, longest, and most complex outbreak since Ebola first emerged in 1976. At the peak of transmission, which occurred during August and September 2014, the country was reporting from 300 to 400 new cases every week.

During those 2 months, the capital city Monrovia was the setting for some of the most tragic scenes from West Africa’s outbreak: gates locked at overflowing treatment centres, patients dying on the hospital grounds, and bodies that were sometimes not collected for days.

So it’s high time I redeemed my promise to return to the ‘war on Ebola‘.

In previous commentaries I discussed the militarisation of the epidemic and, in particular, the mission of the US military under the direction of US Africa Command. But the ‘West Point’ in my title is thousands of miles from the US Military Academy in upstate New York… It’s a sprawling informal settlement in Monrovia, the capital of Liberia (below).

In an extended essay in the New Yorker earlier this year, ‘When the fever breaks‘, Luke Mogelson told the story of Omu Fahnbulleh and her husband Abraham. They lived with their three children in Robertsport in northern Liberia. Last summer Fahnbulleh tested positive for Ebola; by the time an ambulance arrived Abraham was sick too, and they were both loaded into the back and driven off.

Fahnbulleh and her husband believed that they were going to a hospital. Instead, several hours later, the ambulance turned onto a narrow lane that ran past low-slung shops and shanties. Fahnbulleh realized that they were in West Point, Monrovia’s largest slum. A police officer opened a metal gate, and the ambulance stopped inside a compound enclosed by tall walls. In the middle of the compound stood a schoolhouse. The driver helped Fahnbulleh and Abraham through a door, down a hall, and into a classroom. A smeared chalkboard hung on one of the walls, which were painted dark blue. Dim light filtered through a latticed window. On the concrete floor, ailing people were lying on soiled mattresses. When Fahnbulleh lay down, she saw that the two men beside her were dead.

This was the only school in West Point, originally built by USAID, and it had been converted into a ‘holding centre’ for Ebola patients; the only ‘treatment’ on offer was provided by a man in a biohazard suit spraying the floor, the walls and the patients with chlorine. Two nights later Abraham died, and as soon as it was light Fahnbulleh – convinced she would die too if she stayed – determined to escape.

At daybreak, after spending the night in the other classroom, she walked out of the school. Policemen loitered in the yard. When Fahnbulleh reached the gate, they let her pass, afraid to touch her.

After several nights of sleeping rough she was taken to an Ebola Treatment Unit at a government hospital, from where she was eventually discharged.

It’s a heart-breaking story, made all the more extraordinary by a photograph taken by John Moore which shows ‘Omu Fereneh’ standing over the body of her husband ‘Ibrahim’ on 15 August in the schoolhouse. The image was widely reproduced – see also here, for example – and raises important questions about the mediatisation as well as the militarisation of the crisis. Moore’s work won him the title of L’Iris d’Or /Sony World Photography Awards’ Photographer of the Year:

John Moore’s photographs of this crisis show in full the brutality of people’s daily lives torn apart by this invisible enemy. However, it is his spirit in the face of such horror that garners praise. His images are intimate and respectful, moving us with their bravery and journalistic integrity. It is a fine and difficult line between images that exploit such a situation, and those that convey the same with heart, compassion and understanding, which this photographer has achieved with unerring skill. Combine this with an eye for powerful composition and cogent visual narrative, and good documentary photography becomes great.

I’m not sure that Omu Fereneh is Omu Fahnbulleh, or Ibrahim Abraham, but it would be a remarkable coincidence if they were not the same people.

In any event, soon after the photograph was taken and soon after Fahnbulleh escaped, the situation in West Point changed dramatically. Realising that their community had become a dumping ground for Ebola victims from all over Liberia, local residents stormed the schoolhouse and demanded it be closed. They ransacked the building, making off with mattresses and sheets, and evicted over 20 patients who they claimed had been brought in from outside West Point.

Two days later the state called in its security forces which had urged the imposition of mass quarantine. Joe Shute takes up the story:

On August 20, President Ellen Johnson Sirlief ordered the only road leading in to the slum be sealed off, and the entire community placed under quarantine. As the army moved in, many of the city’s vagrants who slept in the slum at night were trapped inside.

West Point was surrounded by barricades and barbed wire; police in helmets and riot-shields stopped people going out into the city; gunships patrolled the water front, and a nightly curfew was imposed on the district’s 70,000 residents. There was, Joe reports, ‘a desperate clamour to escape, some people even trying to swim around the peninsula to enter the city’s port.’

The imposition of a militarised quarantine was a double mis-step.

First, it exacerbated the already precarious position of West Point residents. Many of them were refugees and child soldiers from Liberia’s civil wars; they were crowded together in makeshift corrugated-iron shacks, almost all of them without plumbing or running water. The district is threaded by narrow sand alleys – there is only one paved road – and by open sewers. In 2009 the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported there were only four public toilets in West Point; to use them cost 2-3 cents, and many chose to use the beach instead.

Most of West Point’s residents were dependent on access to the city and the ocean for their livelihood, but with the imposition of the blockade food supplies dwindled and food prices sky-rocketed. As the Institute for Development Studies argued in a Practice Paper on ‘Urbanisation, per-urban growth and zoonotic disease‘ earlier this year:

Poor peri-urban residents, with no money to purchase and store in bulk, buy essentials daily. When lock-down, intended to halt disease spread, occurs, shops, markets and transport facilities are closed, reducing opportunities for peri-urban residents to work and earn cash for food. Many of their activities continue clandestinely, undermining the health intervention. During attempts in West Point to contain the spread of Ebola, people found new ways of moving through the area quarantined in August 2014. Their concern was not exposure to Ebola, but their inability to access food and water.

Some bribed the police to let them out; others, still more desperate, even swam around the point. Here is a report from Norimitsu Onishi writing in the New York Times:

“We suffering! No food, Ma, no eat. We beg you, Ma!” one man yelled at Ms. Johnson Sirleaf as she visited West Point … surrounded by concentric circles of heavily armed guards, some linking arms and wearing surgical gloves.

“We want to go out!” yet another pleaded. “We want to be free, Mama, please.”

Quarantine has to be seen as a political, even a biopolitical response. As the IDS insists,

In the face of Ebola, and with the pressure on governments to act, the peri-urban area becomes an attractive place to intervene. The deployment of the military and the police to quarantine the peri-urban is a tangible manifestation of state power that is oppressive for residents. Thus quarantine-related activities fulfil the political role of assuaging the urban elite’s fears of contagion – ‘cleaning up’ the peri-urban by excluding the poor, rather than helping them or addressing the key challenges of the disease.

And, as Onishi also explained, the political implications were not lost on local residents:

“Putting the police and the army in charge of the quarantine was the worst thing you could do,” said Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe, a Congolese physician who helped identify the Ebola virus in the 1970s, battled many outbreaks in Central Africa and has been visiting Monrovia to advise the government. “You must make the people inside the quarantine zone feel that they are being helped, not oppressed.”

Not surprisingly, the imposition of quarantine provoked concerted collective protest. Hundreds of young men tried to storm the barricades and force their way through the makeshift checkpoint. Soldiers and police opened fire, killing a fifteen-year-old boy.

As Clare Macdougall reported:

“The force was disproportionate, they were already using batons, sticks, they had access to teargas and equipment to things to control an unarmed crowd,” said Counsellor Tiawan Gongloe, Liberia’s most prominent human rights lawyer. “I find it difficult to believe that there was any justification for shooting a 15-year-old boy who was unarmed. This is not a militarized conflict, it is a disease situation and a biological problem.”

Second, as this implies, quarantine is not an effective counter-measure and may well be counter-productive. Sealing off ‘plague towns’ was a medieval and early modern response to infectious disease – remember your Foucault! – but as one commentator noted, ‘isolating a small group of unhealthy people with a large group of healthy residents can cause more harm than good if they don’t get access to food, water and medical care — all of which are in increasingly short supply.’ In fact, transmission of Ebola occurs through bodily fluids once a patient shows symptoms of the disease, which means that the most effective response is not mass quarantine but the isolation of individual cases. This places a premium on contact tracing (you can find another image gallery from John Moore here, tracking a tracing coordinator in West Point; see also my previous post for more details and links on contact tracing).

Following negotiations with community leaders, the government eventually agreed to lift the quarantine. ‘We are out of jail!” declared one triumphant resident.

People celebrate in a street outside of West Point slum in Monrovia, Liberia, Saturday, Aug. 30, 2014. Crowds cheer and celebrate in the streets after Liberian authorities reopened a slum where tens of thousands of people were barricaded amid the countryís Ebola outbreak. The slum of 50,000 people in Liberia’s capital was sealed off more than a week ago, sparking unrest and leaving many without access to food or safe water. (AP Photo/Abbas Dulleh)

Now people started to mobilise in other ways. In return for removing the barriers and barbed wire, Luke Mogelson explained, community leaders implemented other containment measures:

identifying sick people, removing them from the community, quarantining their houses, tracking down their recent contacts, and monitoring those contacts for twenty-one days—the maximum amount of time the virus has been known to incubate before manifesting symptoms. Previously, all this was the responsibility of highly trained specialists…

In West Point, the job fell to the neighborhood. “We had to guarantee that the things that needed to be done would be done by ourselves,” Archie Gbessay, another local leader, who worked with Martu to carry out the interventions, told me one afternoon in November. We were walking down the main road that snakes through West Point. Gbessay wore a knapsack filled with case-investigation forms and kept his thumbs hooked on the chest-strap clipped across his sternum. He is twenty-eight years old but exudes a quiet force that seems to have accrued over a much longer life; his face quivers with intensity when he talks about Ebola. “If we didn’t do this, nobody was going to do it for us,” he said.

To build a network of active case-finders who could cover all of West Point, Gbessay recruited three volunteers from each of the slum’s thirty-five blocks. Most of them were young and had a degree of social clout—“credible people,” Gbessay called them. The quarantine had done little to alleviate popular skepticism of the government’s Ebola-containment policies, however, and, for a while, hostility persisted. “At first, the cases were skyrocketing,” Gbessay said. “We used to see seventy, eighty cases a day. But by the middle of September everyone started to think, Look, I better be careful. Today, you talk to your friend—tomorrow, you hear the guy is gone. So they started to pay attention.”

Otis Bundor, a contact tracer in West Point, described his day’s work and emphasised the importance of a trust that depended on local knowledge and on being known:

At the beginning of the outbreak, people were afraid to tell us if their family members were sick. They worried about stigmatization, and they were frightened that their wife or sister or son would go to the hospital and never come back. Some people thought that health workers were injecting patients with poison. As a contact tracer, you need to have the intellectual prowess to convince doubters that Ebola is real…

At first, family members hid bodies and buried them under the cover of darkness. This is one of the reasons that the disease became an epidemic. Attitudes changed only when people noticed that in almost all of the houses where someone died, another person later got sick. In one household, more than seven people died after they vehemently prevented contact tracers from entering.

But gradually contact tracing – or, more accurately, the contact tracers – became accepted as something other than policing. By the time Luke Mogelson visited West Point the holding centre in the schoolhouse had reopened as a transit centre:

Now, when residents of the slum felt unwell, they came here to be diagnosed and, if necessary, wait for an ambulance that was staffed by West Pointers and managed by Martu. The average wait time had become a matter of minutes, rather than days.

In September, at the height of the outbreak in Monrovia, the C.D.C. warned that Ebola could infect 1.4 million West Africans by late January. The prediction assumed that no “changes in community behavior” would occur. By November, that assumption was obsolete in West Point. Gbessay’s active case-finders had largely prevailed on their neighbors to come forward with symptoms and observe basic precautions such as avoiding physical contact with each other and washing their hands several times a day at the hundreds of chlorine buckets stationed throughout the city. As a result, cases were waning. “Every day, patients come,” the supervisor of the transit center told me. “But it’s going down. It’s getting less and less.”

And as Lenny Bernstein noted, this turn-around ‘has occurred without the provision of a single treatment bed by the U.S. military, which has promised to build 17 Ebola facilities containing 100 beds each across Liberia.’

Pingback: Covid-19 and armed conflict | geographical imaginations

Reblogged this on Progressive Geographies and commented:

Derek Gregory with another thoughtful and strikingly illustrated post on Ebola in Liberia.