I’ve already noted the effect that William Boyd‘s An Ice-Cream War (1982) had on me, but there’s another Boyd novel that also deals with the First World War – this time set on the Western Front rather than East Africa – that also offers much food for thought.

I’ve already noted the effect that William Boyd‘s An Ice-Cream War (1982) had on me, but there’s another Boyd novel that also deals with the First World War – this time set on the Western Front rather than East Africa – that also offers much food for thought.

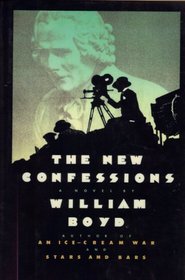

In the early sections of The New Confessions (1987), an odyssey conducted in the obvious shadows of Rousseau, the protagonist John James Todd is serving in a Public School service battalion of the British Army just before Ypres. In a chapter revealingly entitled ‘New geometries, new worlds’, Todd recalls the Ypres front in early June 1917 like this:

‘Take an idealized image of the English countryside – I always think of the Cotswolds in this connection… Imagine you are walking along a country road. You come to the crest of a gentle rise and there before you is a modest valley. You know exactly the sort of view it provides. A road, some hedgerowed lanes, a patchwork of fields, a couple of small villages – cottages, a post-office, a pub, a church – there a dovecote, there a farm and an old mill; here an embankment and a railway line; a wood to the left, copses and spinneys scattered randomly about. The eye sweeps over these benign and neutral features unquestioningly.

‘Now place two armies on either side of this valley. Have them dig in and construct a trench system. Everything in between is suddenly invested with new sinister potential: that neat farm, the obliging drainage ditch, the village at the crossroads become key factors in strategy and survival. Imagine running across those intervening fields in an attempt to capture positions on that gentle slope opposite so that you may advance one step into the valley beyond. Which way will you go? What cover will you seek? How swiftly will your legs carry you up that sudden gradient? Will that culvert provide shelter from enfilading fire? Is there an observation post in that barn? Try it next time you are on a country stroll and see how the most tranquil scene can become instinct with violence. It only requires a change in point of view.’

Later Todd is recruited by the War Office Cinema Committee with strict instructions about what and may not be shown, and some ten years after he wrote the novel Boyd directed his own film, The Trench, set on the eve of the Battle of the Somme. But my point (for the moment) isn’t about photography or film but about the work of war artists on the Western Front.

Later Todd is recruited by the War Office Cinema Committee with strict instructions about what and may not be shown, and some ten years after he wrote the novel Boyd directed his own film, The Trench, set on the eve of the Battle of the Somme. But my point (for the moment) isn’t about photography or film but about the work of war artists on the Western Front.

During the spring of 1916 Charles Masterman, the director of the British War Propaganda Bureau, was persuaded to appoint the first Official War Artist, Muirhead Bone. Bone was a sketcher and watercolour artist, who was duly commissioned as an honorary Second Lieutenant and arrived in France during the Battle of the Somme. He returned to England in October, and two hundred of his drawings were published in ten monthly parts, with an accompanying commentary by C.E. Montague.

‘For many people at home,’ Samuel Hynes remarks in A war imagined, ‘they must have been an important source of their notions of what the war looked like.’ But, he continues,

‘Bone and Montague agreed that what it looked like was England; both the drawings and the commentaries imagine the war in familiarizing English terms… They made the war look familiar, and they provided images of it from which both the dead and the suffering living had been entirely excluded.’

When the first two weekly installments appeared, apparently to considerable public acclaim, Wilfred Owen called them ‘the laughing stock of the army’ because they presented such a pastoralized, picturesque and sanitized view of the war: ‘To call it England!’ Many of Bone’s drawings, like the two examples I’ve shown here, rendered the landscape in the idealized terms of Boyd’s ‘country stroll’. (There were exceptions, but even when Bone turned to the desolation of the battlefield many of his sketches were devoid of human form, alive or dead.) To be sure, most commentators noted that in the rear a working countryside persisted, and many of them made much of the shocking transition from a landscape that was indeed familiar, largely untouched by military violence, to something unlike any landscape on earth.

And it’s exactly that anti-landscape Owen wanted to be represented. In The soldiers’ tale Hynes writes that

‘War turns landscape into anti-landscape, and everything in that landscape into grotesque, broken, useless rubbish – including human limbs.’

And there were other artists who were developing Boyd’s ‘change in point of view’, a different visual vocabulary for these brutally new warscapes. One of the most interesting, I think, is C.R.W. Nevinson. Early in the war Nevinson served as an orderly with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit and then as an ambulance driver with the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was invalided out in January 1916, a result of acute rheumatic fever, but in March 1916 he exhibited a series of Futurist paintings whose stark geometric planes and mechanised violence conveyed a radically different sensibility, one in which soldiers and machines were fused into shockingly new assemblages and where human bodies were caught up in and overwhelmed by the percussive force of the new military machine. One of his most famous paintings, of a French machine-gune post, La Mitrailleuse (below), captures what Michael Walsh calls the ‘machinomorphic image’ of the war.

And there were other artists who were developing Boyd’s ‘change in point of view’, a different visual vocabulary for these brutally new warscapes. One of the most interesting, I think, is C.R.W. Nevinson. Early in the war Nevinson served as an orderly with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit and then as an ambulance driver with the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was invalided out in January 1916, a result of acute rheumatic fever, but in March 1916 he exhibited a series of Futurist paintings whose stark geometric planes and mechanised violence conveyed a radically different sensibility, one in which soldiers and machines were fused into shockingly new assemblages and where human bodies were caught up in and overwhelmed by the percussive force of the new military machine. One of his most famous paintings, of a French machine-gune post, La Mitrailleuse (below), captures what Michael Walsh calls the ‘machinomorphic image’ of the war.

Walter Sickert claimed that La Mitrailleuse ‘will probably remain the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting’, but other Nevinson paintings of this period capture other dimensions of the automations of the killing machine, as in Column on the march (1915):

They also captured, through what Claude Philips praised as their ‘cold, calculated violence’ and ‘cruel, metallic angularity’, what Henri Lefebvre once called ‘the overwhelming of the human body’, as in The strafing (1915):

In invoking Lefebvre here, I have in mind this passage from The production of space where he describes a modern, abstract, geometric space:

‘… space has no social existence independently of an intensive, aggressive and repressive visualization. It is thus – not symbolically but in fact – a purely visual space. The rise of the visual realm entails a series of substitutions and displacements by means of which it overwhelms the whole body and usurps its role.’

And yet, of course, the production of this extraordinarily violent space was literally shot through with corporeal investments.

I’ve described these artworks as Futurist, but two riders are necessary. The first, and most obvious, is that Marinetti‘s own Manifesto of Futurism expressed a desire ‘to glorify War – the only health giver of the world’, and while Nevinson was fascinated by, even infatuated with Marinetti – he sent Marinetti a postcard (right) of him posing in front of his ambulance, without any discernible sense of irony – this was a claim that Nevinson eventually explicitly repudiated (in a column for the Daily Express called ‘Painter of Smells at the Western Front’). Bone, incidentally, liked Nevinson’s work.

I’ve described these artworks as Futurist, but two riders are necessary. The first, and most obvious, is that Marinetti‘s own Manifesto of Futurism expressed a desire ‘to glorify War – the only health giver of the world’, and while Nevinson was fascinated by, even infatuated with Marinetti – he sent Marinetti a postcard (right) of him posing in front of his ambulance, without any discernible sense of irony – this was a claim that Nevinson eventually explicitly repudiated (in a column for the Daily Express called ‘Painter of Smells at the Western Front’). Bone, incidentally, liked Nevinson’s work.

The second is more interesting. Paul Saint-Amour has described aerial photography and interpretation on the Western Front not as an applied realism but as an applied modernism – and with good reason (some interpretation manuals described ‘Cubist’ and ‘Futurist’ landscapes) – and if we extend this insight then we might say that in these artworks Nevinson was recovering and reinscribing a scopic regime that was instrumental in the very violence he sought to subvert.

In March 1917 Nevinson was toying with the idea of putting his talents to work in the new camouflage section of the army, but by July he was back in France as an Official War Artist. He went up in an observation balloon and claimed to be ‘the first man to paint in the air’; in fact he thought his ‘aeroplane pictures the finest work I have done’. But in many of these later paintings he turned his back on Futurism and the machinations of the killing fields and restored the broken body to the art of war. The most notable example is perhaps Paths of glory (1917). Refused permission to exhibit the canvas at the Leicester Galleries in London by the War Office, Nevinson had it displayed with a brown paper sticker across the two dead bodies reading “Censored”…

There is an excellent gallery of Nevinson’s work here, and for more discussion I recommend David Boyd Hancock, A crisis of brilliance: five young British artists and the Great War (2010); Michael Walsh, ‘C.R.W. Nevinson: conflict, contrast and controversy in paintings of war’, War in History 12 (2) (2005) 178-207, and his two books, C.R.W. Nevinson: This cult of violence (2002) and Hanging a rebel: the life of C.R.W. Nevinson (2008).

Pingback: Staging the landscapes of war – with noises off | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Hide and Seek – and Show « geographical imaginations

Pingback: 3-D War « geographical imaginations