In his classic memoir, A rumor of war, Philip Caputo recalled reading a series of US Army manuals about what was in store before he deployed to Vietnam. Once there, flying over the rainforest,

In his classic memoir, A rumor of war, Philip Caputo recalled reading a series of US Army manuals about what was in store before he deployed to Vietnam. Once there, flying over the rainforest,

‘Looking at the green immensity below, I could only conclude that those manuals had been written by men whose idea of a jungle was the Everglades National Park. There was nothing friendly about the Vietnamese bush; it was one of the last of the dark regions on earth…’

I’ve been reading those Field Manuals on Jungle Warfare too, but in the illuminating light of Dan Clayton‘s wonderfully suggestive essay on ‘Militant tropicality’ [Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (2013) 180-192], and three thematics have emerged so far.

First, the manuals worked to displace pre-existing imaginative geographies: in effect, they reassured the young soldier, ‘it’s all in the mind’. The strategy was already in place in the dog-days of the Second World War. FM 72-20 on Jungle Warfare, issued in October 1944, had this to say:

‘As in any area where physical hardship is the rule, there are accompanying psychological reactions to the jungle. These reactions take the form of magnifying the physical hardships and the inherent dangers of warfare. Limited visibility increases the feeling of insecurity, strange noises assume an increased importance, and men tend to become jumpy and panicky. The dull, shaded light and, in many areas at certain periods of the day, the gloomy, drifting mists of jungle areas have a morose and eerie effect which further adds to the feeling of insecurity.’

By 1965 the new FM 31-30 on Jungle training and operations, was still warning against ‘prevalent misconceptions’ (over-imaginative geographies, I suppose):

‘The soldier who is not familiar with the jungle will suffer from conditioned fears and apprehensions when faced with the prospect of living and fighting in a jungle environment. Popular representation of the jungle as being a veritable green hell of large trees and dense underbrush growing over vast expanses of flat, swampy ground and inhabited by thousands of animals, snakes, and insects which are hostile to man, cause this fear. Before such individuals even set foot in the jungle they are appalled at the prospect of doing so. Certainly the foreboding appearance of the jungle, the oppressive humidity and heat, the unfamiliar noises, and the abject feeling of loneliness that one feels when entering the jungle intensify the already existing fear of the unknown. It cannot be denied that the jungle presents some most unpleasant aspects. But the individual must, through systematic and thorough training and acclimation, learn to know the jungle for what it actually is and not for what it is supposed to be or what it might be. Once this knowledge is acquired, the soldier will respect the jungle, not fear it.’

Second, the manuals encouraged soldiers – as Caputo noted – to see that ‘the jungle can be your friend’. Again, the terrain had been prepared by FM 72-20:

‘In jungle warfare, the soldier often fights two enemies: man and nature. The elimination of nature as an enemy and the use of the jungle itself as an ally are training objectives fully as important as the elimination of the human enemy. The soldier must be trained not to fight the jungle; he must be capable of living successfully in it and making it work for him against the human enemy.’

By 1965, the manual exuded a breezy self-confidence. While it conceded that ‘the jungle itself is an obstacle’ to visibility (so the soldier must ‘develop his senses of smell, hearing and touch to a high degree’) and to movement (‘vines that entangle and trip even the most careful person, steep stream banks with slippery soils, shrubs and trees with thorns that penetrate and tear clothes, grasses with knife-like and saw-toothed edges that cut the skin’), it also affirmed that ‘no obstacle is insurmountable or impenetrable.’ If this sounds uncomfortably close to Monty Python’s cheerful enjoinder to ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life‘, the manual did indeed go to considerable pains to minimise the snares and dangers of the rainforest:

‘Most animals in the jungle will not attack man unless they are frightened… The widespread terror of “the snake- infested jungle” prevalent in the minds of most peoples is an imaginary mental image. It is true that the number and variety of snakes are high in the wet tropics; however, the incidence of poisonous snakes is no higher than in some of the swamp areas of the Temperate Zone.

Presumably including Caputo’s Everglades.

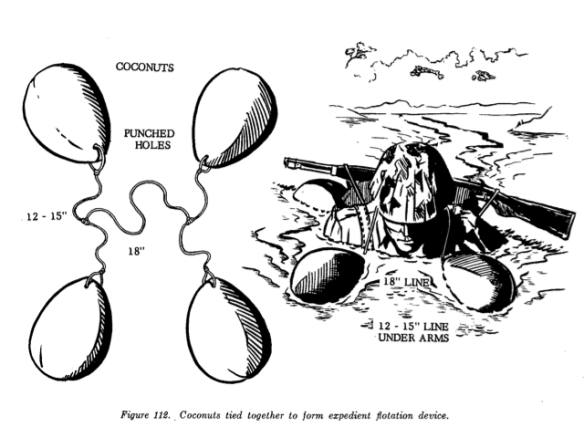

This all went hand-in-hand with an enthusiastic maximisation of the super-abundance of tropical nature, one of the key motifs of tropicality more generally. Dozens of pages were devoted to living off and finding shelter in the jungle, with instructions and diagrams that would not have been out of place in the Boy Scouts of America:

There were also endless photographs of pineapples tangerines, mangoes, limes, bananas, papayas and avocados (see above).

In fact, however, the US military sowed different and deadly tropical fruit. The BLU-3 bomblet, a container filled with 250 steel pellets, was known as a ‘pineapple’ (left); a B-52 bomber could drop 1,000 of them across a 400-yard area, and as they burst open, Nick Turse reports, ‘250,000 lethal ball bearings would tear through everything in their path.’ Another cluster bomb, the CBU-24, was called a ‘guava’, loaded with more than 600 separate bomblets and capable of sending ‘200,000 steel fragments shooting in all directions.’ From 1964 to 1971, Turse reports, the US military ordered at least 37 million pineapples and from 1964 to 1971 at least 285 million guavas. (His key source is Eric Prokosch, The technology of killing: a military and political history of anti-personnel weapons; for one attempt to clear these munitions [from Laos], see Project Pineapple here).

In fact, however, the US military sowed different and deadly tropical fruit. The BLU-3 bomblet, a container filled with 250 steel pellets, was known as a ‘pineapple’ (left); a B-52 bomber could drop 1,000 of them across a 400-yard area, and as they burst open, Nick Turse reports, ‘250,000 lethal ball bearings would tear through everything in their path.’ Another cluster bomb, the CBU-24, was called a ‘guava’, loaded with more than 600 separate bomblets and capable of sending ‘200,000 steel fragments shooting in all directions.’ From 1964 to 1971, Turse reports, the US military ordered at least 37 million pineapples and from 1964 to 1971 at least 285 million guavas. (His key source is Eric Prokosch, The technology of killing: a military and political history of anti-personnel weapons; for one attempt to clear these munitions [from Laos], see Project Pineapple here).

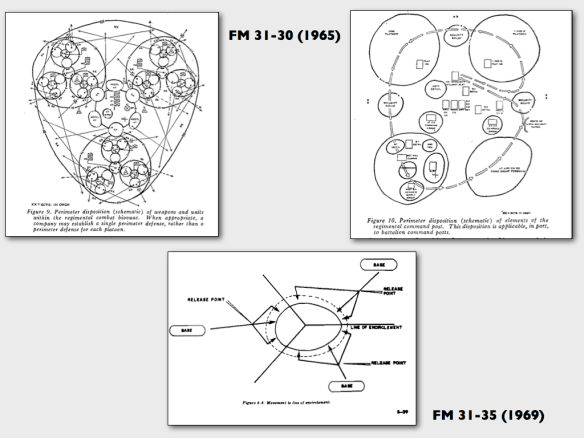

This brings me to the third strategy: disciplining nature through the imposition of military Reason. By 1969 the – edible – ‘fruits of the jungle’ had disappeared from the manuals. After a review of different types of jungle, including ‘Oriental jungles’, the discussion immediately turned to weapons, armour and artillery, air support and chemical and biological warfare, so that ‘nature’ was militarised and subjected to military (re)ordering much earlier in the revised manual. The emphasis was on ‘modification’ of Standard Operating Procedures, which had also been a key element four years earlier, and a continued move away from the tangle of the jungle – what Tim O’Brien would later call in Going after Cacciato ‘a botanist’s madhouse’ – to the superimposition of ordered combat geometries like those I’ve extracted below.

This brings me to the third strategy: disciplining nature through the imposition of military Reason. By 1969 the – edible – ‘fruits of the jungle’ had disappeared from the manuals. After a review of different types of jungle, including ‘Oriental jungles’, the discussion immediately turned to weapons, armour and artillery, air support and chemical and biological warfare, so that ‘nature’ was militarised and subjected to military (re)ordering much earlier in the revised manual. The emphasis was on ‘modification’ of Standard Operating Procedures, which had also been a key element four years earlier, and a continued move away from the tangle of the jungle – what Tim O’Brien would later call in Going after Cacciato ‘a botanist’s madhouse’ – to the superimposition of ordered combat geometries like those I’ve extracted below.

In effect, the military sought to plane away ‘Nature’ and reduce it to an abstract ‘Space’. Of course, the imposition of military Reason on what was now (de)constructed as a militantly ‘un-natural Nature’ was more than a paper affair, and it was invariably violent. In his Matterhorn: a novel of the Vietnam War, Karl Marlantes describes the construction of a fire support base on a mountain top so that an artillery unit, helicoptered in, could range its fires over the rainforest below:

‘The defensive lines grew more distinguishable. No longer were they made up of holes that blended in with the earth and the mass of torn limbs and brush. The holes had been transformed into naked, angular structures, stark against the denuded hillside, looking like sturdy little boxes poking out from the slope.’

There was an elaborate, constantly changing network of these bases, but here is what this could look like; this is Fire Support Base 29, Dak To, in the Central Highlands in June 1968:

To be sure, ecological destruction took many forms beyond the Rome plow (there’s a video of its deployment in land-clearing operations here) and violent explosions from artillery and aircraft. The widespread spraying of herbicides like Agent Orange is well known; remember that the slogan of Operation Ranch Hand was ‘We prevent forests’…

And yet, if Vietnam was McNamara’s prized ‘techno-war’, it emphatically did not see the triumph of American science and technology, still less that of their transmutation into an operative military Reason, over an alien ‘Nature’. As Dan Clayton says, ‘an omniscient American war machine was [not] bearing down on a transparent, knowable or compliant battlefield.’ There’s a passage in Frederic Downs‘s The killing zone that captures and counterposes the geometric violence of the war and the resilience of the rainforest to great effect:

The coordinates for that location and the time for firing would be relayed to the gun crews. At the specified time, the gun crews would be awakened. Perhaps it would be just after midnight. As the minutes ticked closer to a time set by an unknown intelligence the men would load the artillery pieces, anticipating the release of their impersonal death into a grid square. The gun commander would give the order to fire and the night would explode with man’s lightning and thunder. After the prescribed rounds, the guns would cease, the cleanup would begin, and the men would go back to their bunks. Thinking what? Within the range of those guns, within a specified area, the Central Highlands had for a brief moment changed from the jungle it had been for thousands of years into the particular insanity of man. As the gun crews wandered back to their bunkers to settle down for the night, the jungle would also begin settling down for the night to begin healing the new wounds.

I’ll have more to say about this in later posts, but for now here’s a passage from Stephen Wright’s novel, Meditations in Green, that sets the scene for the argument I’m developing in ‘The natures of war’:

“Of course, it’s not as if bushes were innocent … Sit on top of a bunker, stare at the tree line for a while. You have to concentrate because if you blink or look away for even a moment you might miss it, they aren’t dumb despite what you may think, they’re clever enough to take only an inch or two at a time. The movement is slow but inexorable, irresistible, maybe finally unstoppable. A serious matter.”

“What movement, what are you are you talking about?”

“The trees, of course, the fucking shrubs. And one day we’ll look up and there they’ll be, branches reaching in, jamming our M-60s, curling around our waists.”

“Like Birnam Wood, huh?”

“Actually, I was thinking more of triffids.”

These other jungle books have a lot to tell us about war too.

Pingback: Footprints of War | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Terror and terrain | geographical imaginations

Thanks so much Teo; I’m sure you’re right and I’ll follow up Emperors in the Jungle. Caputo, like many others, also traces US doctrine back to the British in Malaya:

‘We practiced tactics perfected by the British during the Malayan uprising in the 1950s, a conflict that bore only a facile resemblance to the one in Indochina. Nevertheless, it was the only successful counterinsurgency waged by a Western power in Asia, and you could not argue with success. So, as always seems to be the case in the service, we were trained for the wrong war; we learned all there was to know about fighting guerrillas in Malaya.’

That’s as may be, but – as Dan Clayton notes – Robert Thompson, a British veteran of counterinsurgency in Burma and Malaya and a Kennedy adviser, complained that most US commanders in Vietnam couldn’t ‘see the woods for the defoliated trees.’

Thanks for this Derek, lots of stuff I will be following up on. I think an important reference is also Emperors in the Jungle: The Hidden History of the U.S. in Panama by John Lyndsay-Poland. The book, among other things, talks a good deal about Panama as a laboratory and proving ground for the U.S. military’s approach to fighting in/against tropical jungles, climates, and peoples. Besides the Everglades, I guess, there was also Panama. I suspect many of the FMs you cite sprouted in part from the Pentagon’s involvement in and around its military-commercial enclave in Panama.

Reblogged this on rhulgeopolitics and commented:

Terrific posting on jungles and war natures (in different senses of the term: environment/nonhumans/affective sensibilities/systems) over at geographical imaginations.