Back in November 2012 I explained that the debate over CIA-directed targeted killing in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere risked overlooking the conduct of targeted killing by the US military and its coalition partners in Afghanistan:

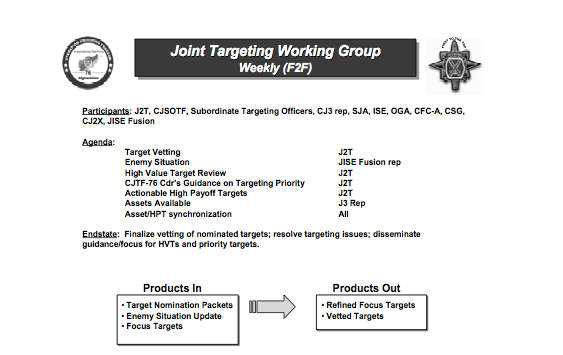

Targeted killings are also carried out by the US military – indeed, the US Air Force has advertised its ability to put ‘warheads on foreheads’ – and a strategic research report written by Colonel James Garrett for the US Army [‘Necessity and Proportionality in the Operation Enduring Freedom VII Campaign‘] provides a rare insight into the process followed by the military in operationalising its Joint Prioritized Effects List (JPEL). Wikileaks has provided further information about JSOC’s Task Force 373 – see, for example, here and here – but the focus of Garrett’s 2008 report is the application of the legal principles of necessity and proportionality (two vital principles in the calculus of International Humanitarian Law (IHL)) in counterinsurgency operations. Garrett describes ‘time-sensitive targeting procedures’ used by the Joint Targeting Working Group to order air strikes on ‘high-value’ Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders in Afghanistan, summarised in this diagram:

Notice that the members included representatives from both Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force (CJSOTF) and the CIA (‘Other Government Agency’, OGA). This matters because Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) – once commanded by General Stanley McChrystal – and the CIA, even though they have their own ‘kill lists’, often co-operate in targeted killings and are both involved in strikes outside Afghanistan. Indeed, there have been persistent reports that many of the drone strikes in Pakistan attributed to the CIA – even if directed by the agency – have been carried out by JSOC.

Now Spiegel Online has provided new, detailed information about the Joint Prioritized Effects List and targeted killing in Afghanistan. Its base materials – some of which come from the Snowden cache – cover the period 2009-2011 and include an anonymised version of the JPEL (extract below).

The Spiegel team explains:

[This is] the first known complete list of the Western alliance’s “targeted killings” in Afghanistan. The documents show that the deadly missions were not just viewed as a last resort to prevent attacks, but were in fact part of everyday life in the guerilla war in Afghanistan.

The list, which included up to 750 people at times, proves for the first time that NATO didn’t just target the Taliban leadership, but also eliminated mid- and lower-level members of the group on a large scale. Some Afghans were only on the list because, as drug dealers, they were allegedly supporting the insurgents.

As I’ve said, the JPEL was maintained through close collaboration between the CIA and the US military, including Joint Special Operations Command, so it is not surprising that the list is not confined to Afghanistan but also includes Pakistanis who were located inside Pakistan.

We already know that targeted killings inside Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas involved signal intelligence from the NSA, Britain’s GCHQ and Australia’s Pine Gap facility. Spiegel‘s cache of documents shows that coalition states outside the ‘Five Eyes’ (US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) were included in the wider Center Ice platform that also supplied geospatial intelligence for tracking and targeting. Taken together:

Predator drones and Eurofighter jets equipped with sensors were constantly searching for the radio signals from known telephone numbers tied to the Taliban. The hunt began as soon as the mobile phones were switched on.

Britain’s GCHQ and the US National Security Agency (NSA) maintained long lists of Afghan and Pakistani mobile phone numbers belonging to Taliban officials. A sophisticated mechanism was activated whenever a number was detected. If there was already a recording of the enemy combatant’s voice in the archives, it was used for identification purposes. If the pattern matched, preparations for an operation could begin. The attacks were so devastating for the Taliban that they instructed their fighters to stop using mobile phones.

The document also reveals how vague the basis for deadly operations apparently was. In the voice recognition procedure, it was sufficient if a suspect identified himself by name once during the monitored conversation. Within the next 24 hours, this voice recognition was treated as “positive target identification” and, therefore, as legitimate grounds for an airstrike. This greatly increased the risk of civilian casualties…

[In addition] Center Ice was not just used to share intelligence about mobile phone conversations, but also information about targets.

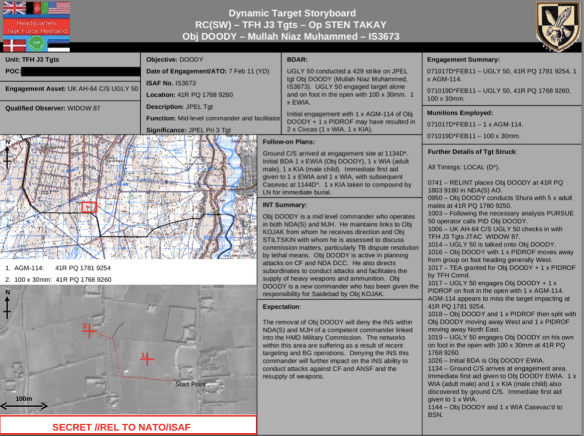

Finally – and directly relevant to that penultimate paragraph – Spiegel includes a detailed post-strike ‘Dynamic Target Storyboard‘ that explains how one mission executed by a British AH-60 helicopter (callsign/codename UGLY 50) armed with Hellfire missiles missed its target (‘Objective DOODY’, a mid-level Taliban commander called Mullah Niaz Muhammed categorised as JPEL ‘level 3’) on its first pass and then, coming in for a second attack, seriously wounded an innocent father and killed his child:

To navigate the storyboard – a standard ‘after action’ report – you need to wade through an alphabet soup of acronyms, some of which I know and others I don’t. Working left to right along the top line, the mission was under the control of TFH – ISAF’s Task Force Helmand – whose main component was provided by the UK military; under BDAR (Battle Damage Assessment and Repair) the AH-64 attack helicopter is identified as operating under ISAF Rules of Engagement 429 (the details of all these ROEs remain classified). The Intelligence Summary shown below identifies the target as ‘Objective DOODY’, provides skeletal details of his activities, and links him with two other targets on the JPEL, ‘KOJAK’ and ‘STILTSKIN’ (presumably part of the military’s standard social network analysis).

The far right column provides further information about the attack. At 0741 intelligence (ELINT is electronic intelligence, but RELINT is not included in the Ministry of Defence’s acronym list) places ‘DOODY’ in Nad-e-Ali (South); by 0950 he is holding a meeting with five other men, and at 1003 a ‘PURSUE 50 operator’ [how I would like to know more about what means] confirms positive identification (PID) which denotes ‘reasonable certainty that this is a legitimate military target’. Shortly afterwards, a Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC), listed as a ‘Qualified Observer’ with the grim call sign WIDOW 87, contacts the helicopter crew and talks them on to the target: once they have him in their field of view they are ready to attack. What isn’t clear from all this is whether the JTAC is relying on a video feed from a drone – this seems the most likely source, and an aerial view is included on the storyboard, tracking the target’s movements once the attack is under way – or whether s/he is on the ground (unlikely, I think, since ground troops take more than an hour to arrive on site after the attack: see ‘Follow-on Plans’ box).

When the target walks away from the meeting, accompanied by one man, the helicopter crew is cleared to engage both of them (TEA) (I’ve explained PID but if anyone knows what PIDROF means please let me know since that seems to authorise killing his unknown and unnamed companion).

According to a supplementary page on the storyboard file, shown below, the AH-64 makes its initial run but fails to engage and returns for a second attempt; in doing so, the crew loses visual identification of the target, what the military usually calls the ‘visual chain of custody’, and at 1017 fires a Hellfire missile which misses the nominated target and instead causes fragmentation injuries to two civilians nearby (marked 1 on the aerial view). The helicopter returns again; by then ‘DOODY’ and his companion have parted company, and the crew fires 100 rounds from its 30 mm cannon at ‘DOODY’, leaving him seriously wounded (EWIA: ‘enemy wounded in action’; marked 2 on the aerial view).

Over an hour later, at 1134, ground troops arrive to capture ‘DOODY’ – but they also find one other seriously wounded man and the body of his young son. The boy is buried by his family, and the casualties are airlifted to the military hospital at Camp Bastion (BSN); ‘DOODY’ is later transferred to Kandahar for further treatment for a serious head wound.

ISAF launched an investigation into the incident, but no details have been released.

So: two innocent, unnamed bystanders killed. As more evidence unfolds of the inaccuracies of ‘targeted killing’, even when the target is supposedly named and identified (so not a ‘signature strike’), it seems that we should start talking about the prevalence of untargeted killing…

Pingback: Meatspace? | geographical imaginations

Pingback: In continent | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Angry Eyes (2) | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Angry Eyes (1) | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Little Boys and Blue Skies | geographical imaginations