I promised to post the notes for my presentation of ‘Angry Eyes: the God-Trick and the geography of militarised vision‘, and this is the first instalment (illuminated by some of the slides from the presentation). This isn’t the final, long-form version – and I would welcome comments and suggestions on these notes – but I hope it will provide something of a guide to where I’m coming from and where I’m going.

In many ways, this is a companion to ‘Dirty Dancing: drones and death in the borderlands’ (I’ll post the full text version of that shortly; until then see here, here and here), but that essay examines aerial violence in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan, tracing the long history of air strikes in the region, from Britain’s colonial ‘air policing’ of its North West Frontier through the repeated incursions by Afghan and Soviet aircraft during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan (which are missing from most critical accounts) to today’s drone strikes directed by the CIA and air raids conducted by the Pakistan Air Force. ‘Angry Eyes’ focuses instead on a series of US air strikes inside Afghanistan.

(1) Eyes in the Sky

The history of aerial reconnaissance reveals an enduring intimacy between air operations and ground operations. Balloons and aircraft were essential adjuncts to army (and especially artillery) operations; before the First World War most commentator insisted that the primary use of military aircraft would be to act as spotters for artillery, enabling the guns to range on distant targets, and that bombing would never assume a major offensive role. As I’ve noted elsewhere, Orville Wright was among the sceptics: ‘I have never considered bomb-dropping as the most important function of the airplane,’ he told the New York Times in July 1917, ‘and I have no reason to change this opinion now that we have entered the war.’ For him – though he did not altogether discount the importance of striking particular targets, like the Krupp works at Essen – the key role of the aeroplane was reconnaissance (‘scouting’) for ground forces, including artillery: ‘About all that has been accomplished by either side from bomb dropping has been to kill a few non-combatants, and that will have no bearing on the result of the war.’ That was, of course, a short-sighted view – even in the First World War aircraft carried out strikes against targets on and far beyond the battlefield – but the sharper point is that the importance of aerial reconnaissance depended on a version of what today would be called networked war (albeit a desperately imperfect one) (see my ‘Gabriel’s Map [DOWNLOADS tab]; for the pre-war history of bombing, see here; for the bombing of Paris in the First World War see here).

Over the next 50 years the technologies of vision changed dramatically: from direct to indirect observation, from delayed to real-time reporting, and from still to full motion imagery.

And the ligatures between seeing (or sensing) and shooting steadily contracted until these functions were combined in a single platform – notably (but not exclusively) the Predator and the Reaper. Even then, wiring aerial operations to ground manoeuvres often (even usually) remains central:

Remarks like these speak directly to Donna Haraway’s cautionary critique of the ‘God-Trick’: the claim to see everything from nowhere, or at least from a privileged ‘vanishing point’. This has been made explicit by Lauren Wilcox in Bodies of Violence:

… the satellite systems and the drone’s video cameras mean that the bomber’s eye view is the God’s eye view of objectivity… this myth is put into practice in the apparatus of precision bombing, in which the view from above becomes the absolute truth, the view from nowhere.

And – Haraway’s point, which has been sharpened by Wilcox – is that this view from nowhere is, in some substantial sense, a view from no-body (and even of no-body). Here is Owen Sheers in his novel I saw a man:

“A U.S. drone strike.” That was all the press release said. No mention of Creech, screeners, Intel coordinator, an operator, a pilot. It was as if the Predator had been genuinely unmanned. As if there had been no hand behind its flight, no eye behind its cameras.

The appeal to the divine is thus more than a rhetorical device. One Predator pilot admitted that ‘Sometimes I felt like God hurling thunderbolts from afar.’ As Wilcox notes, then,

The appeal to the divine is thus more than a rhetorical device. One Predator pilot admitted that ‘Sometimes I felt like God hurling thunderbolts from afar.’ As Wilcox notes, then,

‘Precision bombing reproduces the illusion of a disembodied subject with not only a privileged view of the world, but the power to destroy all that it sees…. The posthuman bodies of precision bombers, relying on God’s eye, or panoptical, views are produced as masterful, yet benign, subjects, using superior technology to spare civilians from riskier forms of aerial bombardment.’

And yet there have been seemingly endless civilian casualties…

(2) Killing and casualties in Afghanistan

Throughout the US-led occupation of Afghanistan, air strikes have been the overwhelming cause of civilian deaths caused by coalition forces:

As Jason Lyall‘s marvellous work shows (below), air strikes have been concentrated in the south. I should note that the title of his map refers explicitly to ISAF air operations – I’m not sure if this includes those conducted under the aegis of Operation Enduring Freedom, a separate US-UK-Agfghan operation, although a primary source of his data is USAF Central Command’s Airpower Statistics. It makes a difference, for reasons I’ll explain later; the strike that is my primary focus took place in the south (in Uruzgan) but was in support of a Special Forces operation conducted under OEF.

In any event, most of those strikes have been carried out from conventional platforms – strike aircraft or attack helicopters – not drones (though notice how the data on weapons released from Predators and Reapers was rapidly removed from the regular Airpower Statistics issued by US Central Command):

This relates to a specific period, and one might expect drone strikes to become even more important as the numbers of US ground troops in Afghanistan fall. Even so:

- in many, perhaps most of those cases drones have provided vital intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities: in effect, they may well have orchestrated the attacks even if they did not execute them;

- according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism [‘Tracking drone strikes in Afghanistan‘], ‘Afghanistan is the most drone bombed country in the world… Research by the Bureau… has found more than 1,000 drone attacks hit the country from the start of 2008 to the end of October 2012. In the same period, the Bureau has recorded 482 US drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and Libya’; and

- where drones have also carried out the attacks, Larry Lewis’s analysis of classified SIGACT data shows that ‘unmanned platforms [are] ten times more likely to cause civilian casualties than manned platforms’ (see also here)

There have been two main forms of air strike in Afghanistan. First, the US military carries out so-called ‘targeted killing’ there as well as elsewhere in the world; it has its own Joint Prioritized Effects List of people deemed to be legitimate military targets (see here and here), and the supposed capacity of its drones and their crews to put ‘warheads on foreheads’ means that they are often involved in these remote executions.

Even so, these operations have certainly caused the deaths of innocent civilians (see, notably, Kate Clark‘s forensic report on the Takhar attack in September 2010: more here).

Second, the US Air Force also provides close air support to ground troops – and civilian casualties are even more likely to result from these situations, known as ‘Troops in Contact’.

As Marc Garlasco noted when he was working for Human Rights Watch:

“When they have the time to plan things out and use all the collateral damage mitigation techniques and all the tools in their toolbox, they’ve gotten to the point where it is very rare for civilians to be harmed or killed in these attacks. When they have to do it on the fly and they are not able to use all these techniques, then civilians die.”

That said, it is simply wrong to claim that the US military is indifferent to civilian casualties. There have been several major studies of civilian casualties (see also here and here).

In addition, the juridification of later modern war means that military lawyers (JAGs) are closely involved in operational decisions (though the laws of war provide at best a limited shield for civilians and certainly do not outlaw their deaths); Rules of Engagement and Tactical Directives are issued and modified; and investigations into ‘civilian casualty incidents’ (CIVCAS) are established at the commander’s discretion. Of most relevance to my own argument is General Stanley McChrystal‘s Tactical Directive issued on 6 July 2009.

This was not window-dressing. Here is Michael Hastings in his by now infamous profile of McChrystal in Rolling Stone (8 July 2010):

McChrystal has issued some of the strictest directives to avoid civilian casualties that the U.S. military has ever encountered in a war zone. It’s “insurgent math,” as he calls it – for every innocent person you kill, you create 10 new enemies. He has ordered convoys to curtail their reckless driving, put restrictions on the use of air power and severely limited night raids. He regularly apologizes to Hamid Karzai when civilians are killed, and berates commanders responsible for civilian deaths. “For a while,” says one U.S. official, “the most dangerous place to be in Afghanistan was in front of McChrystal after a ‘civ cas’ incident.” The ISAF command has even discussed ways to make not killing into something you can win an award for: There’s talk of creating a new medal for “courageous restraint,” a buzzword that’s unlikely to gain much traction in the gung-ho culture of the U.S. military.

Indeed, McChrystal’s actions were fiercely criticised: see Charles Dunlap here (more here).

(3) Predator View

And so I turn to one of the most extensively documented CIVCAS incidents in Afghanistan: an attack on three vehicles near the village of Shahidi Hassas in Uruzgan province in February 2010, which killed at least 15-16 civilians and injured another 12. This has become the ‘signature strike’ for most critical commentaries on drone operations:

In the early morning of 21 February 2010 a US Special Forces team of 12 soldiers (these are always described as Operational Detachment Alpha: in this case ODA 3124) supported by 30 Afghan National Police officers and 30 Afghan National Army troops flew in on three Chinook helicopters to two locations near the village of Khod. This is an arid, mountainous region but Khod lies in a river valley where an extensive irrigation system has been constructed to create a ‘green zone’:

On a scale from 0 to 2, this was a ‘level 1 CONOPS’, which means that it was judged to pose a ‘medium risk’ to the troops with ‘some potential for political repercussions’. These are usually daylight cordon and search operations with air support. In this case the mission was to search the compounds in and around the village for a suspected IED factory and to disrupt ‘insurgent infrastructure’.

The Taliban clearly knew they were coming. While the troops waited for dawn the scanners on their MBITR radios picked up chatter urging the mujaheddin to gather for an attack, and they passed the frequency to an AC-130 gunship which was providing air support; through their night vision goggles the troops could see figures ducking into the cover provided by the irrigation ditches; and communications intercepted by other support aircraft, including a manned electronic signals intelligence platform referred to only by its call sign ‘Arrow 30’, confirmed a strong Taliban presence.

There were reports of vehicles moving towards the village from the south, and then headlights were detected five kilometres to the north. The AC-130 moved north to investigate. It had an extensive sensor suite on board but its resolution was insufficient for the crew to detect whether the occupants of the vehicles were armed [PID or ‘positive identification’ of a legitimate military target], and so they co-ordinated their surveillance with a Predator that had taken off from Kandahar Air Field and was controlled by a crew (call-sign KIRK 97) at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada. In addition to its Multi-Spectral Targeting System, the Predator was equipped with an ‘Air Handler’ that intercepted and geo-located wireless communications; this raw signals intelligence was handled by an ‘exploitation cell’ (almost certainly operated by a National Security Agency unit at Kandahar) who entered their findings into one of the chat-rooms monitored by the Predator and other operations centres that were involved in the mission.

When the AC-130 started to run low on fuel, the Predator took over ISR for the duration of the mission. The JTAC could not see the trucks from his position on the ground, and neither did he have access to the full-motion video feed from the Predator – the ODA was not equipped with a ruggedised laptop or ROVER [Remote Operational Video Enhanced Receiver] that should have been standard equipment (‘There’s one per base, and if it goes down you’re out of luck’) – and so he had to rely entirely on radio communications with the flight crew.

Throughout the night and into the morning the crew of the Predator interpreted more or less everything they saw on their screens as indicative of hostile intent: the trucks were a ‘convoy’ (at one stage they were referred to as ‘technical trucks’); the occupants were ‘Military Aged Males’ (’12-13 years old with a weapon is just as dangerous’); when they stopped to pray at dawn this was seen as a Taliban signifier (‘I mean, seriously, that’s what they do’); and when the trucks swung west, away from the direct route to Khod, this was interpreted as ‘tactical manoeuvring’ or ‘flanking’.

Eventually the ground force commander with ODA 3124 became convinced of hostile intent, and anticipated an imminent ‘Troops in Contact’. This in turn prompted the declaration of a precautionary ‘AirTIC’ to bring strike aircraft on station since the Predator only had one Hellfire missile onboard. The ground force commander was annoyed when fighter aircraft arrived (call-sign DUDE 01) – ‘I have fast movers over my station, my desire is to have rotary-wing aircraft’ – because he believed the engine noise would warn the target. In fact, the JTAC who had access to intercepts of Taliban radio communication confirmed that ‘as soon as he showed up everyone started talking about stopping movement’; coincidentally, as it happened, the vehicles immediately swung west, heading away from Khod.

Two US Army Kiowa combat helicopters (OH-58s, call-sign BAM-BAM) were now briefed for the attack.

Their situation map (below) confirmed this as a landscape of ever-present threat, and this imaginative geography was instrumental in the reading of the situation and the activation of the strike:

Meanwhile, the Predator’s sensor operator was juggling the image stream, switching from infrared to ‘Day TV’ and trying to sharpen the focus:

The helicopters had their own sensor system – a Mast Mounted Sight (MMS) – but its resolution was low (see below); they were also reluctant to come in low in case this warned the target:

In any case, there were severe limitations to what the pilots could see:

So, for all these reasons, they were reliant on what the Predator crew was telling them (they too had no access to the FMV feed from the Predator). They lined up for the shot, and the Predator crew keenly anticipated being able to ‘play clean up’. ‘As long as you keep somebody that we can shoot in the field of view,’ the Predator pilot told his Sensor Operator, ‘I’m happy.’

Throughout the mission the Predator crew had been communicating not only by radio but also through mIRC (internet relay chat); multiple windows were open during every mission, but KILLCHAIN was typed into the primary chat room to close down all ‘extraneous’ communications during the final run so that the crew could concentrate on executing the strike.

The ground commander through the JTAC cleared the helicopters to engage: ‘Type Three’ on the slide above refers to a control situation in which the JTAC can see neither the target nor the strike aircraft and wishes to authorise multiple attacks within a single engagement. According to the US Air Force’s protocols for terminal control:

Type 3 control does not require the JTAC to visually acquire the aircraft or the target; however, all targeting data must be coordinated through the supported commander’s battle staff (JP 3-09.3). During Type 3 control, JTACs provide attacking aircraft targeting restrictions (e.g., time, geographic boundaries, final attack heading, specific target set, etc.) and then grant a “blanket” weapons release clearance to meet the prescribed restrictions. The JTAC will monitor radio transmissions and other available digital information to maintain control of the engagement.

Hellfire missiles from the helicopters ripped into the trucks, and when the smoke cleared those watching – from the helicopters and on screens at multiple locations in Afghanistan and the continental United States – began to suspect that women and children were clearly in the field of view. A team from ODA 3124 was helicoptered in to co-ordinate the evacuation of casualties and to conduct a ‘sensitive site exploration’.

It turned out that the occupants of the vehicles were all Hazaras who were vehemently anti-Taliban (4,000 Hazara had been massacred by the Taliban at Mazar-i-Sharif in August 1998); they were going to Kandahar for a variety of reasons – shopkeepers going for supplies, a mechanic going to buy spare parts, students returning to school, patients seeking medical treatment, others simply looking for work – and they were travelling together (‘in convoy’) for safety through what they knew was Taliban territory. When civilian casualties were eventually confirmed – which is a story in itself – General McChrystal set up an Informal Investigation.

Most commentators (including me in “From a view to a kill”: DOWNLOADS tab) have endorsed the central conclusion reached by the Army investigation:

But this was not the conclusion reached by the USAF Commander’s Directed Investigation into the actions of the Predator crew (which McChrystal ordered when he received McHale’s report). Major-General Robert Otto conceded that ‘the Predator crew’s faulty communications clouded the picture on adolescents and allowed them to be transformed into military-aged males’, but he insisted that their actions were otherwise entirely professional:

‘Upon INFIL and throughout the operation, extensive Intercepted Communications (ICOM) chatter correlated with FMV and observed ground movement appeared to indicate a group of over thirty individuals were an insurgent convoy…. Kirk 97 did not display an inappropriate bias to go kinetic beyond the desire to “support the ground commander”. The crew was alert and ready to execute a kinetic operation but there was no resemblance to a “Top Gun” mentality.’

The reference was to a statement made to McHale’s team by a captain at Creech:

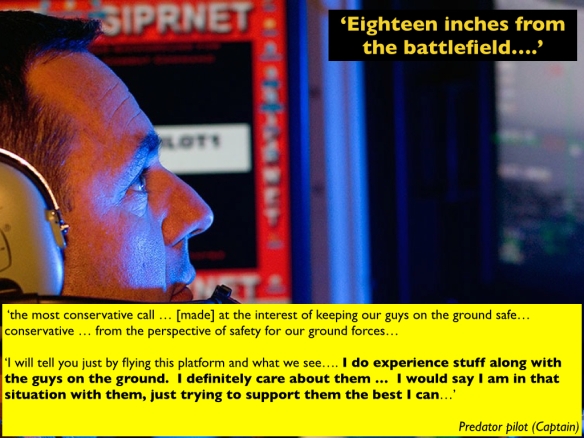

Be that as it may, the last clause– the desire ‘to help out and be part of this’ – is, I think, substantial. As I argued in “From a view to a kill”, most Predator and Reaper crews insist that they are not thousands of miles from the battlefield but just eighteen inches away: the distance from eye to screen. There is something profoundly immersive about the combination of full-motion video and live radio communication; perhaps the crews who operate these remote missions over-compensate for the physical distance to the troops on the ground by immersing themselves in a virtual distance that pre-disposes them to interpret so much that appears on their screens as hostile and threatening.

So far, so familiar. But two qualifications impose themselves.

First, virtually all the published accounts that I have read – and the one that I have published – draw on a detailed report by David S. Cloud, ‘Anatomy of an Afghan war tragedy‘, that appeared in the Los Angeles Times on 10 April 2011, which was based on a transcript of radio communications between the Predator crew, the helicopter pilots and a Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) who was relaying information to and from the ground force commander. But according to Andrew Cockburn, McHale’s original investigation compiled a hand-drawn timeline of events that ran for 66 feet around the four walls of a hangar he had commandeered for his office; his investigation ran to over 2,000 pages of evidence and transcripts. It’s a complicated, composite document: a record of transactions – of conversations, negotiations and interrogations inflected by the chain of command – made at different times, in different places and under different circumstances. Redactions make inference necessarily incomplete, and there are inevitably inconsistencies in the accounts offered by different witnesses. So I need to be cautious about producing a too coherent narrative – this is not the tightly integrated ‘network warfare’ described by Steve Niva in his excellent account of Joint Special Operations Command (‘Disappearing violence: JSOC and the Pentagon’s new cartography of networked warfare’, Security dialogue 44 (2013) 185-202).

Still, when you work through those materials a radically different picture of the administration of military violence emerge. In his important essay on ‘The necropolitics of drones’ (International Political Sociology 9 [2015] 113-127) Jamie Allinson uses McHale’s executive summary to demarcate the kill-chain involved in the incident:

The US military “kill chain” involved in the Uruzgan incident comprised ground troops, referred to in the text as “Operational Detachment Alpha” (ODA), the Predator Drone operators based at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada, the “screeners” processing information from the Predator video feeds at Hurlburt Field Base in Florida, and helicopter gunships known as ‘OH-58D’ in the text. The helicopters fired the actual missiles: but this was on the basis of decision made by drone operators based on their interpretation of what the screeners said.

But – as I’ll show in the second instalment – the kill-chain was far more extensive and included two Special Forces operations centers at Kandahar and Bagram that were responsible for overseeing and supporting the mission of ODA-3124.

The significance of this becomes clearer – my second qualification – if the air strike in Uruzgan is analysed not in isolation but in relation to other air strikes that also produced unintended casualties. As a matter of fact, official military investigations are required to be independent; they are not allowed to refer to previous incidents and, indeed, JAGs who advise on targeting do not routinely invoke what we might think of as a sort of ‘case law’ either. But if this air strike is read in relation to two others – an attack by two F-15E strike aircraft on a tanker hijacked by the Taliban near Kunduz on 4 September 2009, and an attack carried out by a Predator in the Sangin Valley on 6 April 2011 – then revealing parallels come into view. All three were supposed to involve ‘Troops in Contact’; the visual feeds that framed each incident – and through which the targets were constituted as targets – were highly ambiguous and even misleading; and the role of the ground force commander and the operations centers that were supposed to provide support turns out to have been critical in all three cases.

To be continued.

Pingback: Derek Gregory, Under Afghan Skies – Prologue and Part I | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Under Afghan Skies: prologue | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Eyes in the sky – bodies on the ground | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Those who don’t count and those who can’t count | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Aerial violence and the death of the battlefield | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Seeing Civilians (or not) | geographical imaginations

Pingback: A landscape of interferences | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Meatspace? | geographical imaginations

Pingback: National Bird | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Rights and REDACTED | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Film Review: Eye in The Sky | The Law of Killer Robots

Pingback: Still reaching from the skies… | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Matters of definition | geographical imaginations

Pingback: A lack of intelligence | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Watching the detectives | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Angry Eyes (2) | geographical imaginations