As promised in my previous post, here is the first installment of my essay on an airstrike on three vehicles in Uruzgan, Afghanistan on 21 February 2010; the incident was widely reported – see the images immediately below this prefatory note – and, for reasons I explain in detail below, it has become a central focus for critics of remote warfare.

The images in the body of the text are taken from my conference presentation, but the version that will appear in “Reach from the sky” will have different images and a number of specially drawn maps. I have also added a number of direct links to some of the sources I cite.

For the otherwise unattributed page references in the text, see note 38 below.

Under Afghan Skies: Aerial violence and the imaginaries of remote warfare

Your eyes aren’t eyes. They’re bees.

I can find no cure for their sting. [1]

Contemporary conflict takes many different forms, from siege warfare to cyber-war, but it is the military drone that has captured the public imagination. Like other modalities of later modern war the drone is a combination of the remarkably old and the radically new – visions and even versions of ‘unmanned’ platforms have a history as long as that of aerial violence itself – but its twenty-first century incarnation occupies a central place in the Western iconography of wars fought in the global borderlands since 9/11.

The drone has assumed such prominence in those shattered lands for several reasons, not the least of which is that its deployment is confined to uncontested air space – by default or design [2] – because advanced militaries would have no difficulty in shooting such a comparatively slow and sluggish platform out of the sky. [3]

It is thus no accident that the drone has become a standard means of waging ‘unconventional’, asymmetric warfare against non-state actors. And yet, even though Afghanistan has long been the epicentre of drone warfare, the figure of the drone may not be central to the political imaginary of the Afghan Taliban, which rarely distinguishes between different forms of airstrike or between aerial violence and other forms of explosive violence. [4] This is not altogether surprising. Predators and Reapers fire exactly the same weapons as many conventional strike aircraft and combat helicopters, and in a war zone like Afghanistan this often makes it difficult to identify the source of an attack. This is not to say that the people of Afghanistan – particularly those who have witnessed airstrikes – have not learned to distinguish and dread the buzzing of drones overhead. Like other unwilling members of what Lisa Parks describes as the ‘new disenfranchised class of ”targeted people”’ whose daily lives are ‘haunted by the spectre of aerial bombardment’, they know only too well that the audible and sometimes visible presence of a drone can foreshadow a sudden strike from the sky. [5]

Many of the most powerful critical commentaries on military drones have drawn attention to an airstrike on three vehicles on 21 February 2010 near the mountain pass of Khotal Chowzar that straddles the provinces of Daikundi and Uruzgan in southern Afghanistan. This was a pre-emptive response to what was seen – literally so – as a threat to US Special Forces and Afghan forces conducting a counterinsurgency operation in the village of Khod in Uruzgan. [6] After the strike it became clear that all the casualties – in fact, all the occupants of the vehicles – were civilians. They came from a cluster of poor villages in Daikundi, and included men hoping to find work in Iran, students returning to university, shopkeepers and mechanics going to buy stock and spares, and men and women attending medical appointments or taking their children to visit relatives. Most of them were Hazaras – a tribe with a long history of persecution by the majority Pashtun and more recently by the Taliban [7] – who were travelling together for support and safety.

The vehicles were heavily laden and had to stop frequently for repairs as they slowly bumped their way on dirt roads on a circuitous route to the mainly paved national Highway 1 – the Ring Road – that would take some of them south to Kandahar, some west to Herat and beyond, and others north to Kabul. The Ring Road was damaged and dangerous. The Taliban had attacked not only traffic on the highway (notably military supply convoys) but also bridges, causeways and culverts, forcing drivers to detour on to dirt tracks, and once back on the road they had to run the gauntlet of checkpoints manned by insurgents and criminal gangs who exacted ‘tolls’ for their passage. [8] But this first stage through the mountains was perilous too. The ground was rough, the tracks were in poor condition and several rivers had to be forded. More unsettling, all the adults in the vehicles knew that they were travelling through the heart of Taliban country. But none of them expected the danger to come from the sky. Nasim, a car mechanic travelling in one of the SUVs, explained: ‘We weren’t worried when we set out. We were a little scared of the Taliban, but not of government forces… Why would they attack us?’[9] In fact, several of the US military observers watching the live video feed from an MQ-1 Predator drone that had been tracking the vehicles for hours and who saw the strike go down were at first convinced that they had hit an IED (improvised explosive device) planted by the Taliban.

It is still not clear how many victims of the airstrike there were, but the US Army made 23 compensation payments (solatia) to the families of those who were killed, and 12 survivors were airlifted to military hospitals where they received emergency treatment for what, in several cases, were life-changing injuries. [10]

The Uruzgan attack was but one of many air strikes in Afghanistan that caused multiple civilian casualties (Figure 1).

Afghanistan was the focus of US drone strikes during this period – other target areas were Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Somalia and Yemen – but drone strikes in Afghanistan were far outweighed by conventional bombing. US Central Command (CENTCOM) reported that coalition aircraft released 4,163 weapons – bombs and missiles – in Afghanistan in 2009, of which 255 (6.1 per cent) were from remote platforms; 5,102 in 2010, of which 278 (5.4 per cent) were from remote platforms; and 5,409 in 2011, of which 294 (5.4 per cent) were from remote platforms. [11] These (dis)proportions are undoubtedly important – critics need to widen their focus to address aerial violence in all its forms – and yet these raw figures fail to capture the wider significance of remote platforms. Even when their own weapons were not fired, drones were routinely used to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) for air strikes from conventional platforms. And when they did release their own bombs or missiles, one study using SIGACT data from Afghanistan in 2010-11 found that drones were ten times more likely to cause civilian casualties than conventional strike aircraft. [12] These considerations help to explain concern about remote warfare, but the Uruzgan attack attracted widespread attention for three more particular reasons.

First, it flew in the face of significant operational changes introduced the previous year by General Stanley McChrystal, commander of both US Forces–Afghanistan and the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), that were expressly designed to prevent incidents like it. His intervention was the most recent in a series of attempts to limit civilian casualties caused by coalition forces. On 27 and 29 April 2007 US Special Forces conducting counterinsurgency operations in the Zerkoh valley in Herat province in northwest Afghanistan had called in repeated airstrikes from US Air Force AC-130 gunships and other aircraft. ISAF announced that scores of suspected Taliban had been killed with no civilian casualties, but later reports claimed that between 40 and 60 civilians had been killed, dozens more injured and hundreds of homes damaged. [13] In response, ISAF’s commander General Dan McNeill issued a first Tactical Directive in June 2007 requiring advance estimates of likely civilian casualties (‘collateral damage estimates’) before planned strikes and stipulating that air power should only be used as a last resort ‘when forces are taking fire from [a residential] compound or there is an imminent threat from the compound, and when there are no other options available.’The effects of the initial Tactical Directive were limited – not for nothing was its architect known as ‘Bomber’ McNeill – and the civilian toll continued to mount. Then, on 22 August 2008, airstrikes by a US Air Force AC-130 gunship and an MQ-9 Reaper in support of ground operations led by US Special Forces in the village of Azizabad in the same region of Herat province killed as many as 92 civilians. McNeill’s successor General David McKiernan issued a second Tactical Directive on 2 September 2008 that emphasised the importance of a graduated escalation of force and imposed additional constraints on airstrikes that risked causing civilian casualties. McKiernan also established a Civilian Casualty Tracking Cell, required all allegations of civilian casualties to be reported and investigated promptly, and emphasized the connection between minimizing civilian casualties and securing the cooperation of the local population.[14]

This was widely seen as a turning point in the air war in Afghanistan, yet what Bob Dreyfuss described as the ‘steady drum-beat of mass casualty incidents’ did not let up. [15] The next pivotal incident occurred on 4 May 2009, when repeated airstrikes near the village of Granai in Farah province, carried out by US Air Force F-18 fighter jets and a B-1 bomber in support of ground operations by Afghan forces and US Marines, killed at least 26 and perhaps as many as 147 civilians. The catastrophe prompted the newly appointed McChrystal to tighten the Rules of Engagement (ROE) – classified theatre-specific orders issued by senior military commanders that delineate the circumstances and limitations under which lethal force may be used (within the parameters of International Humanitarian Law) – and to issue a third Tactical Directive on 2 July 2009 that enjoined ‘commanders at all levels to scrutinize and limit the use of force like Close Air Support (CAS) against residential compounds and other locations likely to produce civilian casualties.’ Although McChrystal made it clear that his intention was not to prevent commanders opening fire in self-defence when there were no other options available, he was no less adamant that ‘the use of air-to-ground munitions and indirect fires is only authorised under very limited and prescribed conditions’ (which remained classified). [16]

McChrystal’s intervention attracted fierce criticism from the hawks circling the Pentagon – just three days before the Uruzgan attack an op-ed in the New York Times complained that ‘the pendulum has swung too far in favour of avoiding the deaths of innocents at all costs’ [17] – but although the new policy enjoyed more success than its predecessors it also suffered major setbacks. [18] In the early hours of 4 September 2009, two months after the revised Tactical Directive was issued, a German ISAF commander in Kunduz ordered two US Air Force F-15 fighter jets to attack two fuel tankers that had been hijacked by the Taliban. The vehicles had become stranded on a sandbank as they tried to ford the shallow Kunduz river, and the Taliban asked local villagers to siphon off the fuel so the tankers would be light enough to drive off. When the pilots saw the crowds of people on their screens they were reluctant to strike and instead proposed a show of force to scatter the villagers. But their objections were overruled by the Bundeswehr commander, who declared a ‘TIC’, meaning ‘Troops in Contact’ – even though his garrison at Fort Kunduz was 10 km away and there were no other coalition forces in the vicinity – and cleared the pilots to engage purportedly in self-defence. [19] Estimates of civilians killed varied from 60 to more than 140. McChrystal was furious. It was a matter of what he called ‘insurgent math’: for every innocent person killed, 10 new enemies were created. [20] ‘For a while,’ according to one US official, ‘the most dangerous place to be in Afghanistan was in front of McChrystal after a CIVCAS [civilian casualty] incident.’ [21] This was more than a clever remark. CENTCOM’s Deputy Combined Force Air Component Commander at the time argued that McChrystal’s efforts to minimise civilian casualties ‘were based not just in changes to written guidance, but in the day-to-day forceful interaction between McChrystal and his commanders.’ In his view, the third Tactical Directive was not a marked departure from its predecessors; what made the difference was McChrystal’s ‘emphasis on “tactical patience” and daily accountability’. [22] After the Kunduz debacle, McChrystal ordered an immediate investigation and emphasised to his commanders that ‘we need to know what we are hitting.’ [23]

Second, the Uruzgan attack – which came less than six months later – was carried out not by conventional strike aircraft but by two US Army helicopters, a tactic known as Close Combat Attack (CCA) that had been developed ostensibly to enable a more refined use of force than the Close Air Support (CAS) deployed in the Granai and Kunduz incidents. [24] CCA can be traced back to the Korean war, and was in part a contrivance – an attempt to agree the boundaries between the mission sets of the US Air Force and US Army aviation [25] – but many of those who directed ground operations in Afghanistan (including the Ground Force Commander at Khod) believed that the use of armed helicopters, coming in ‘low and slow’, allowed for a more discriminating use of airpower in the vicinity of friendly forces – whose safety was the main consideration – than the Air Force’s high-flying ‘fast movers’.

Whatever the merits of the distinction, it must seem strange to make an attack carried out by helicopters a test case for remote warfare. But the airstrike in Uruzgan was orchestrated through an MQ-1 Predator that had been launched from Kandahar Air Field by a forward-deployed flight crew and then handed off to a mission crew from the 15th Air Reconnaissance Squadron at Creech Air Force Base located 35 miles outside Las Vegas. [26] The Predator’s on-board systems were accessed via a C-band line-of-sight data link for launch and recovery at Kandahar, and then a Ku-band satellite data link, a portal at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, and a fibre-optic cable under the Atlantic and across the continent to the Ground Control Station at Creech.

The aircraft was equipped with a Multi-Spectral Targeting System controlled by a sensor operator (a technical sergeant) sitting on the right of the pilot (a captain) in the Ground Control Station. [27] It transmitted full-motion video (FMV) in infra-red (IR) or colour in near real-time to the flight crew and across multiple military networks in Afghanistan and the United States, including video analysts (‘screeners’) from the 11th Intelligence Squadron of the 1st Special Operations Wing at Hurlburt Field in the Florida Panhandle. [28] The FMV feed was supposed to allow a more accurate targeting process than the lower resolution screens that were standard on conventional strike aircraft: in other words – McChrystal’s words – to enable those involved ‘to know what they were hitting.’ Indeed, a senior US military lawyer had predicted that the digital technologies used on these remote platforms – their capacity to represent the battlespace with unrivalled clarity and to record cascades of events for subsequent review – would give ‘unprecedented traction, transparency, and relevance’ to legal protocols and operational procedures designed to protect civilians. [29] That claim – a version of what Donna Haraway called more generally ‘the God-trick’ – has properly been a central object of critical attention, and part of my purpose is to show that this critique needs to be supplemented by the recognition of a dispersed and distributed geography of militarized vision. [30]

But the Uruzgan attack became the diagnostic case for critics of remote warfare for a third reason through which the pivotal role of the Predator was brought into unusually sharp focus. Coalition headquarters in Kabul did not become aware of the presence of civilian casualties until the early evening of 21 February, but within hours of being briefed McChrystal ordered a full investigation into the incident (p. 1189-90). This was defined as an ‘Informal Investigation’ governed by US Army Regulation 15(6), and Major-General Timothy McHale was appointed as investigating officer. McChrystal’s charge to the investigation ran to three pages and consisted of 20 detailed, numbered questions and procedural instructions.McHale was assisted by five senior officers, who joined him for interviews with the witnesses and provided expert advice on ground combat, aviation, special operations and ground liaison. He was also assisted by five legal advisers and paralegals. The two senior legal advisers were also involved in the interviews, and their presence underscored that this was a quasi-juridical process. Witnesses had to make sworn statements, and McHale’s findings had to be ‘supported by a preponderance of the evidence’ and his recommendations had to be ‘legally consistent with the findings’ (pp. 15-16). The team flew from Kabul to Kandahar Air Field on 22 February, which was their base for the next several weeks; they conducted multiple interviews there, some by phone with witnesses in the United States and others in person at other locations in Afghanistan. It was a wide-ranging investigation, ‘informal’ only in the sense that it was a fact-finding exercise rather than a hearing against a named respondent, which meant that it was not subject to the strict rules of evidence or to the standard of proof applicable in criminal proceedings. [31] In practice it was rigorous, detailed and forensic, and McHale made major findings of fault and recommended reprimands or admonishments for three Army commanders and three staff officers (pp. 65-6).

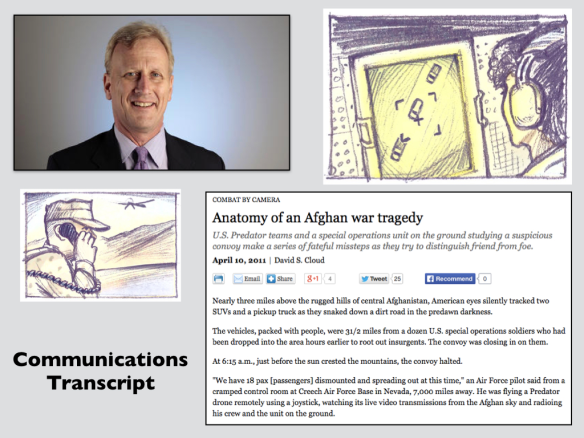

McHale submitted his final report on 18 April 2010, McChrystal approved its findings on 21 May, and a redacted version of the Executive Summary was published one week later and widely reported. A key document in the investigation was the communications transcript of intercom exchanges between the members of the Predator crew in the United States and radio exchanges between the Predator pilot and the forward air controller – the Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) – on the ground with the Special Forces in Afghanistan. The Los Angeles Times obtained a 65-page redacted version of the transcript – the original ran to 75 pages – and published it on 10 April 2011 as part of a detailed reconstruction of the attack by journalist David Cloud. The dramatic and at times chilling exchanges recorded in the communications transcript opened a rare window into the conduct of remote warfare and provided the optic through which virtually all critics have viewed the attack. [32]

That window has since been closed because the public release of information on drone strikes has been severely restricted, especially by the Trump administration. In consequence, even though the Uruzgan attack was carried out in circumstances that no longer apply – ISAF’s combat mission ended in December 2014 and was replaced by the limited (still NATO-led) Operation Resolute Support, a ‘train, advise and assist’ mission, and the United States currently has less than 10,000 ground troops in Afghanistan [33] – and it was co-ordinated by a remote platform no longer in active service – production of the Predator ended in 2011 and the US Air Force retired the remaining aircraft in March 2018 – the incident retains a unique importance for the critical analysis of remote operations.

In relying on the communications transcript critics have inevitably focused on the conduct of the Predator crew and followed their tracking of the three vehicles up to the moment of impact and its immediate aftermath. This has led them to endorse and elaborate one of the main findings of the Army investigation, albeit in different terms, and to attribute central (sometimes even sole) responsibility to the Predator crew.

The commanding officer of the 15th Air Reconnaissance Squadron at Creech had done his very best to forestall that verdict. After his crew had completed their telephone interviews, he called McHale’s team to express his (and their) concern that ‘you guys … [think] they were out to employ weapons no matter what’ (p. 879). One of the investigators took him through the communications transcript, suggesting that the Predator crew displayed a clear and chronic disinclination to believe the vehicles ‘could be anything other than a threat formation’ (p. 887). He identified 19 passages where there appeared to be ‘a predisposition or proclivity to make sure this was confirmed as a good target’ and 13 where the Predator crew modified the assessments from the screeners accordingly. ‘Every time there is a representation of something other than a target,’ he argued, ‘until after the strike there is pushback’ (p. 882). Their commanding officer protested that this was confined to intercom exchanges amongst the crew – which he said was the product of their collective experience and their frustration at the screeners’ reluctance to make definitive calls [34] – and that the pilot never allowed it to cloud his radio communications with the JTAC (pp. 880-1). He followed up with two e-mails within four hours of each other, arguing that even if his crew had been ‘leaning forward’ – in favour of a strike – this had been started by the JTAC who ‘was already leaning extremely far forward’. ‘Upon arrival on the scene,’ he wrote, ‘there were numerous indications passed to the crew by [the JTAC] that implied an imminent kinetic event’ and that it was his transmissions – not theirs – that most clearly revealed ‘a predisposition to shoot’ (p. 898). McHale was unconvinced. ‘A pervasive theme throughout several interviews’, his report concluded, ‘and seen through the internal crew dialogue, was the desire to go kinetic’ (to use lethal force) (p. 33). This propensity – which McHale suggested derived from a pervasive ‘Top Gunmentality’ amongst the Predator crews at Creech [35] – ‘skewed their reports’ to such a degree that they were at once inaccurate and unprofessional and materially distorted the decision field of the Ground Force Commander who cleared the helicopters to strike (p. 61). This was strong language, but McHale’s ability to censure the Predator crew was limited because this was an Army investigation and as such he could fault its conduct but make no disciplinary recommendations. The most he could do (and did) was call for the Air Force to carry out its own investigation. [36]

On my reading, the assessments of the commanding officer at Creech and McHale’s team both had merit. As I will detail in what follows, the Predator crew was drawn into a pre-existing interpretive matrix constructed by other actors, on the ground and in the air, in which the imperative to strike the vehicles had already been established and accepted. But the Predator crew clearly (and enthusiastically) joined in the continued elaboration of the vehicles as a threat formation and they did nothing to challenge that perception; on the contrary, they heightened it.

Most critics go beyond these matters of individual and collective responsibility to address what they see as structural features of remote warfare. McHale’s ability to do so was circumscribed because, even as he drew conclusions and made recommendations to guide future operations, he had to conform to the protocol that prevents informal investigations from considering other, comparable incidents. But what McHale did do was connect aerial violence – the cardinal medium of remote warfare – to the conduct of ground operations. It bears repeating that all the incidents that prompted the three Tactical Directives involved airstrikes in support of ground forces(‘troops in contact’). [37] Although ground operations are often close-in and visceral, they too have their remote dimensions because they are embedded in extended networks of command and control that, while they increasingly draw on FMV feeds from remote platforms, are not circumscribed by them. McHale had much to say about the inadequacies of those networks, and the failings of the actors located within them, so that to recover the deadly interaction between air and ground – to understand what happened to the occupants of those three vehicles on that early February morning – requires a close reading of his full report and its indictment of the failings of other actors outside Creech Air Base. It simply cannot be closed around the communications transcript.

The record of the Army investigation remained classified until it was released by CENTCOM in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request from the American Civil Liberties Union; the Pentagon initially refused to release the file, but after a court challenge it did so on 20 May 2011. [38] Although the consolidated file has been redacted it is sufficiently detailed to widen the analytical scope to address the other, no less important causes of the incident identified by McHale. The larger set of files consists of more than 2,000 pages, including a differently redacted version of the communications transcript.[39] It makes the interpretive field considerably richer but also more complicated. A central issue is the co-existence of multiple temporalities within the written record. The communications transcript is limited to 21 February, whereas the subsequent interviews (which include many more actors and the victims themselves) took place between 22 February and 8 March 2010.

The resulting file is a composite record of transactions conducted at various times – of conversations, negotiations, interviews and re-examinations – and presents multiple narratives from different points of view and different locations, virtually all of them shaped by the post-strike knowledge of civilian casualties and its implications. As one member of McHale’s team recognised, he (and everyone else) had the ‘unfortunate privilege of 20/20 vision’ and got to watch ‘this movie from the end back’ (pp. 880-1). This matters – the reason for his qualifying adjective – because the challenge for the investigators (and now the rest of us) was to set hindsight aside, as far as possible, and reconstruct what was known (or should have been known) as the situation developed through the early hours of 21 February. [40] The task was made even more difficult because the testimony they elicited was shot through with observation, explanation, speculation, misapprehension, forgetfulness (real or feigned), evasion, and – inevitably – hindsight, all inflected by rank and the loyalty intrinsic to the military chain of command and military culture.

The story that emerges is, unsurprisingly, not a consistent one. Witnesses contradicted one another, and on occasion themselves (several were formally warned that they were suspected of giving false testimony), and there is no grand narrative within which the individual accounts can be reconciled. There are also strategic absences. McHale’s team interviewed the pilot of the Predator, and the senior pilot who was called in as Safety Observer at Creech during the closing minutes of the engagement, but testimony from the sensor operator and his relief is missing from the file.[41] Whether this is the result of a failure to interview the two of them or a poorly collated response to the FOIA request is unclear. [42] The commanding officer of the 15th Reconnaissance Squadron had the whole Predator crew present in his office for the initial telephone interview with McHale’s team, and emphasised the importance of the sensor operators, but the transcript of what segued into the first interview (with the pilot) ends abruptly with no closing formularies, no redactions and no explanation (p. 918). Whatever the reason, this is a highly significant omission. [43] The pilot was the flight commander and conducted virtually all the radio communications with the JTAC assigned to the Special Forces on the ground, but the sensor operator was not only responsible for controlling the Multi-Spectral Targeting System. S/he also assisted the pilot with ‘altitude de-confliction, ROES, SPINS [Special Instructions]’ (p. 903), and participated in the collective production of a running commentary on the video feed and on the likely course of (lethal) action that was focal to the construction of the three vehicles as an imminent threat to coalition forces.

Other gaps in the file are the result of redactions. The final report, the communications transcript and most of the interviews have passages redacted, and there are at least 400 other pages that have been withheld from release for security reasons, but the silences go beyond these blank spaces. McHale’s team viewed the FMV feed from the Predator and the video from the helicopter gun cameras, but neither has been released. All the redacted file provides are two screen captures of a Hellfire missile striking the lead vehicle and its immediate aftermath (p. 8), and a series of still photographs of the destroyed vehicles and their dead occupants (pp. 1755-1762), so that it is impossible to scrutinise the all important imagery that was transmitted before the strike. The communications transcript is also incomplete, because it is confined to intercom exchanges among the Predator crew and radio transmissions between the pilots and the JTAC on the ground, and there is no public record of textual communications via the military’s Internet Relay Chat (mIRC) (apart from scattered references in the subsequent interviews). These constituted far more than small talk. The US military makes extensive tactical use of online messaging through its secure networks because it is usually more reliable than voice communication and allows for the concurrent conversations necessary in multi-actor operations (the Ground Control Station at Creech Air Force Base and the Special Forces Operations Centers at Bagram and Kandahar Air Fields all had multiple chat windows open); it also preserves a text record of observations, decisions and actions for after action review. In addition, it is ideal for distributed, intermittent, low bandwidth environments like Afghanistan where it can be accessed outside the wire on ruggedized laptops and data-enabled satellite phones. In short, mIRC is many ways the raw medium – the textual nuts and bolts – of many military operations, and its absence from public view imposes a significant silence. [44] Where other textual records are available – the transcripts of radio communications (including a separate transcript of radio traffic to and from the helicopters) and the interviews with witnesses – they are written versions of oral exchanges and cannot convey the intonation, emphases or hesitations of the original (though in places these can reasonably be inferred), still less the body language that accompanied them. These are all serious limitations, yet for all the interpretive problems the consolidated file opens a wider view and longer perspective that can considerably enlarge and enhance our understanding of remote warfare. [45]

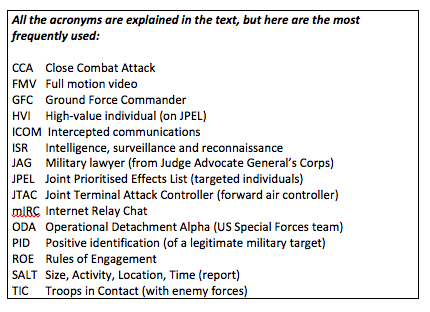

The account that follows is based on a close reading of that file, and is necessarily condensed: McHale’s team reconstructed a time-line that extended for 66 feet round the walls of a hangar. [46] It will also seem as remote as the warfare it describes, at least in the first instance, because much of it is conveyed in the standardised vocabulary of military reason and the military imaginary, with its endless acronyms (see Table 1) (which even the Predator crew forgot on occasion), its abbreviations and its formularies. I gloss these wherever possible – redaction sometimes makes that difficult – but I retain the remote, technical language because abstraction is intrinsic to the execution of calculated forms of military violence and its distancing effect helps to explain how the Uruzgan attack took place. ‘I was an English major in college,’ the Predator pilot testified, ‘so I think semantics can make a big difference’ (p. 913). So it does (and did); yet the language used by him and the other crew members frequently ruptured the dispassionate recitation of military formulae. This was not confined to the aircrew, and I hope it will become clear that the exchanges on 21 February and the days that followed were also animated by affect: by boredom, apprehension, glee, excitement, fear, panic and ultimately horror. The members of McHale’s team were not immune from these emotions either, and at times their exasperation at the responses of some of the officers they interviewed broke the surface of their otherwise impeccably calm, courteous and professional questioning.

NOTES

[1] This is an Afghan landay, a traditional 22-syllable couplet, which I’ve taken from Eliza Griswold, I am the beggar of the world: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014) p. 23; it appears there in the section headed ‘Love’ not ‘War’, but many Afghans compare the buzzing of drones to bees and wasps – and their ‘eyes’ sting too.

[2] In Afghanistan the Taliban has had no air power since its regime was toppled by the US invasion in 2001, and its capacity for a successful ground-to-air strike is limited; in Syria the US routinely de-conflicted the air space with Russia in order to launch airstrikes against Islamic State (IS) positions; and US drone strikes in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan entailed close, covert co-operation between Washington and Islamabad.

[3] In 2020 the US Air Force’s inventory of remote platforms plateaued at six per cent of its total aircraft capacity, as concern was (re)directed towards conflict against major state actors, notably China and Russia, and the ‘non-permissive’ (‘anti-access/area denial’) environments that would entail: Mark Cancian, US Military Forces in FY2020(Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 2019).

[4] Christopher Wyatt and David Dunn, ‘Seeing things differently: Nang, Tura, Zolmand other cultural factors in Taliban attitudes to drones’, Ethnopolitics18 (2019) 201-17. The Pakistan Taliban are likely to have a different view given the role of drones in the execution of the US programme of targeted killing in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas: see Derek Gregory, ‘Dirty dancing: drones and death in the biorderlands, in Caren Kaplan and Lisa Parks (eds) Life in the age of drones (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2017) pp. 25-58 [and DOWNLOADS tab].

[5] Lisa Parks, ‘Drones, vertical mediation and the targeted class’, Feminist Studies42 (1) (2016)227-35: 231.

[6] The incident is almost universally geo-located to Uruzgan, but the Afghan National Army commander who accompanied the US Special Forces insisted that the strike site was just across the border in Daikundi (p. 505), a province created in 2004 from the northern districts of Uruzgan. A researcher who interviewed survivors several years after the attack also located the strike in Kijran District, Daikundi, but when the US Army’s investigation team interviewed them in hospital two days after the strike they said came from three villages in Kijran (p. 1037): Alex Edney-Brown, ‘“I saw pieces of bodies”: Afghan civilians describe terrorization by US drones’, Truthout, 1 July 2017. For the source of otherwise unattributed page references here and elsewhere, see note 38 below.

[7] The Hazaras are Shia and the Pashtun Sunni Muslims. The Hazaras were brutally uprooted from Uruzgan in the nineteenth century by the majority Pashtun, and after mass killings and forcible removals many of them settled in Daikundi. They were marginalized by successive regimes in Kabul, but the rise of the Taliban (a Sunni Islamicist movement) in the 1990s made their position steadily more precarious, and the Taliban carried out mass murders of Hazaras in 1998, 2000 and 2001. But the Hazaras were by no means passive; they were a natural recruiting ground for local anti-Taliban militias. In parts of Uruzgan the militias gained a reputation for exacting revenge on Sunni villages, and in 2010 many of them were recruited into the ‘Afghan Local Police’, who were trained and supported by US Special Forces: May Jeong, ‘The US-trained warlords committing atrocities in Afghanistan’, In these times, 19 September 2017.

[8] Saeed Shah, ‘Dangerous Afghan highway threatens NATO supply flow,’ McClatchy Newspapers, 29 June 2010; On Afghanistan’s roads: extortion and abuse against drivers (Kabul: Integrity Watch Afghanistan, 2013).

[9] David Cloud, ‘Anatomy of an Afghan war tragedy’, Los Angeles Times, 10 April 2011.

[10] The families of those killed each received $5,000; the families of those injured received $3,000. Initial reports also claimed there were three women and three children who were uninjured.

[11] Combined Forces Air Component Commander, 2007-2012 Airpower statistics (AFCENT (CAOC) Public Affairs, 31 December 2012). By 2012 the proportion of strikes carried out from remote platforms in Afghanistan had increased to 10 per cent of weapons released. No detailed breakdown is available after that, but the proportion probably continued to increase (especially during the drawdown of coalition forces). In 2015 coalition aircraft released 947 weapons, a dramatic decline from the height of the air campaign, but 530 (56 per cent) of those bombs and missiles were from remote platforms: Josh Smith, ‘Afghan drone war – data show unmanned flights dominate air campaign’, Reuters, 20 April 2016.

[12] Larry Lewis, Drone Strikes: Civilian Casualty Considerations (Joint Coalition and Operational Analysis, 2013). SIGACTS are ‘significant activities’: violent activities of military significance.

[13] Carlotta Gall and David Sanger, ‘Civilian deaths undermine Allies’ war on Taliban’, New York Times, 13 May 2007.

[14] Civilian harm tracking: analysis of ISAF efforts in Afghanistan (Center for Civilians in Conflict, 2014).

[15] Bob Dreyfuss, ‘Mass casualty-attacks in the Afghan war’, The Nation, 19 September 2017.

[16 ] I have taken these statements from the unclassified version of the Tactical Directive released by ISAF on 6 July 2009. McChrystal prefaced his instructions by emphasizing that ‘We must avoid the trap of winning tactical victories – but suffering strategic defeat – by causing civilian casualties or excessive damage and thus alienating the people.’ See also Dexter Filkins, ‘US tightens airstrike policy in Afghanistan’, New York Times, 21 June 2009. McChrystal’s was neither the last nor the most radical directive; General John Allen issued a fourth revision of the Tactical Directive on 30 November 2011 that was intended ‘to eliminate ISAF-caused civilian casualties across Afghanistan’ and instructed commanders to presume ‘every Afghan is a civilian unless otherwise apparent.’

[17] Lara Dadkhah, ‘Empty skies over Afghanistan’, New York Times,18 February 2010.

[18] In the twelve months after McChrystal’s Tactical Directive was issued, civilian casualties attributed to US and allied forces fell by 28 per cent, and deaths from airstrikes fell by more than 33 per cent: Joseph H. Felter and Jacob B. Shapiro, ‘Limiting civilian casualties as part of a winning strategy: the case of courageous restraint’, Daedalus14 (1) (2017) 44-58.

[19] The declaration of ‘Troops in Contact’ finessed the existing Rules of Engagement, which would have prevented the tankers from being bombed, by ‘manufacturing hostile intent’: E.L. Gaston, When Looks Could Kill: Emerging state practice on self-defence and hostile intent (Global Public Policy Institute, 2017) p. 23. According to two commentators, the Kunduz incident ‘led to the redefining of the term “Troops in Contact” to prevent self-defense criteria from being applied inappropriately’: Sarah Sewall and Larry Lewis, Reducing and Mitigating Civilian Casualties(Joint Civilian Casualty Study, 2011). The Uruzgan attack raised serious questions about the effectiveness of that revision.

[20] ‘From a conventional standpoint, the killing of two insurgents in a group of ten leaves eight remaining… From the insurgent standpoint, those two killed were likely related to many others who will want vengeance’: ISAF Commander’s Counterinsurgency Guidance, 26 August 2009.

[21] Michael Hastings, ‘The runaway General’, Rolling Stone, 8 July 2010.

[22] Lt Gen Stephen Hoog, ‘Airpower over Afghanistan: Observation and Adaptation for the COIN Fight’, in Dag Henriksen (ed), Airpower in Afghanistan: the Air Commanders’ perspectives(Air University Press, Maxwell AFB: 2014) pp. 235-257: 243.

[23] Derek Gregory, ‘Kunduz and “seeing like a military”’, http://www.geographicalimaginations.com, 2 January 2014; Christiane Wilke, ‘Seeing and unmaking civilians in Afghanistan: visual technologies and contested professional visions’, Science, technology and human values 42 (2017) 1031-66.

[24] The US military defines Close Air Support (CAS) as ‘air action by fixed-wing or rotary-wing aircraft against hostile targets that are in close proximity to friendly forces and which require detailed integration of each air mission with the fire and movement of those forces.’ How close? ‘The word “close” does not imply a specific distance; rather it is situational’: Close Air Support, Joint Publication 3-09.3 (8 July 2009; revised 25 November 2014). As the definition makes clear, attack helicopters may be used for CAS but they are preferred for Close Combat Attack (CCA) because they are more flexible than fixed-wing aircraft, slower than those ‘fast movers’ so they can more readily attack difficult targets, and their smaller munitions allow them to fire closer to friendly forces: Maj Patrick Wylde, ‘Close Air Support versus Close Combat Attack’, School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, 2012.

[25] The term CCA was abandoned in the revised edition of US Army Field Manual FM 3.04, Army Aviation (2015).

[26] Redesignated the 15th Attack Squadron on 15 May 2016, the squadron was part of the 432nd Air Expeditionary Wing, which was the first in the US Air Force to be wholly dedicated to the operation of remotely-piloted aircraft (in May 2007).

[27] The Multi-Spectral Targeting System integrated an infra-red sensor, a colour/monochrome daylight TV camera, an image-intensified TV camera, a laser target designator and a laser illuminator into a single sensor package.

[28] Strictly speaking ‘FMV analyst’ is an entry-level position and ‘screener’ is a promoted position; for convenience I refer to all the image analysts as ‘screeners’ (as did the Predator crew). Most missions would have 2 FMV analysts, a screener and a geospatial analyst assigned to support them (p. 1389). The Predator crew also referred to the screeners collectively as ‘DGS’ (Distributed Ground System). The US Air Force’s Distributed Common Ground System (DCGS) is a secure network dedicated to the collection, processing, exploitation and analysis of product from its Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) platforms around the world; its nodes include Distributed Ground Systems (DGS), like the 11thIntelligence Squadron which is part of Air Force Special Operations Command, and more limited Distributed Mission Sites (DMS).

[29] Jack M. Beard, ‘Law and war in the virtual era’, American Journal of International Law103 (2009) 409-45; Beard served as Lieutenant Colonel in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps and as Associate Deputy General Counsel (International Affairs) in the Department of Defense. The protocols and procedures to which Beard referred included International Humanitarian Law and the ROE, but they were conditional: none of them provided absolute protection for civilians in war zones. And Beard’s primary argument concerned the visibility of military actions and the possibility of sanctions if those protocols and procedures were breached – not the visibility of the battlespace: Derek Gregory, ‘From a view to a kill: drones and late modern war’, Theory, culture & society 28 (2011) 188-215: 200.

[30] This would be no surprise to her: see Donna Haraway, ‘Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective,’ Feminist studies 14 (1988) 575-99. On ‘drone vision’ and the God-trick, see Roger Stahl, ‘What the drone saw: the cultural optics of the unmanned war’, Australian journal of international affairs 67 (2013) 659-74; Lauren Wilcox, ‘Embodying algorithmic war: Gender, race, and the posthuman in drone warfare’, Security dialogue 48 (1) (2017) 11-28.

[31] AR 15 (6) Investigating Officer’s Guide (US Army Combined Arms Center, Fort Leavenworth KS); Alon Margalit, ‘The duty to investigate civilian casualties during armed conflict and its implementation in practice’, Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law15 (2012) 155-86: 176. Since 2014 AR 15 (6) investigations have become less common and in their place the less formalized, faster Civilian Casualty Assessment Report (CCAR) has become widely used: for a comparison between the two, see In search of answers: US military investigations and civilian harm (Human Rights Institute, Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict, 2020) pp. 34-5, 39.

[32] Cloud, ‘Anatomy of an Afghan war tragedy’; the transcript is available at http://documents.latimes.com/transcript-of-drone-attack. Extracts from the communications transcript open Grégoire Chamayou, Theory of the drone (New York: New Press, 2015) pp. 1-9 and Andrew Cockburn, Kill Chain: the rise of the high-tech assassins (New York: Holt & Co., 2015) pp. 1-16 (though Cockburn is one of the few to refer to the report as a whole). The most detailed analysis of the Uruzgan incident to date relies entirely on the Times transcript – see Jamie Allinson, ‘The necropolitics of drones’, International political sociology9 (2015) 113-27 – and the transcript also provided the base for the reconstruction of the strike in Sonia Kennebeck’s documentary National Bird (Ten Forward Films, 2016).

[33] Towards the end of 2017 the US Air Force refocused on Afghanistan (from Iraq and Syria) and in October 2017 carried out 653 airstrikes there, the highest number since November 2010; In 2018 US aircraft released 7,362 weapons there and in 2019 they released 4,723; no breakdown is available between conventional and remote platforms.

[34] There were at least two reasons for the screeners’ reluctance. The primary screener was a contractor employed by SCRC, and she explained that the commercial relationship obliged her to err on the side of caution: ‘If I suggest or make an assessment, I have to make sure that I am 100 per cent OK with that decision’ (p. 1391). If the Air Force were to complain about her performance to her employer, she said, ‘that is something that they would take it on themselves to correct’ (p. 1396). For a desperate attempt to shift responsibility to the primary screener, see Maj Keric Clanahan, ‘Wielding a very long, people-intensive spear: inherently governmental functions and the role of contractors in U.S. Department of Defense Unmanned Aircraft Systems missions,’ Air Force Law Review 70 (2013) 119-202, who claims (erroneously) that the decision to strike the three vehicles ‘was largely based upon intelligence analysis conducted and reported by a civilian contractor’ (p. 178). There are many problems with the use of private contractors in military operations, but this was not one of them. Her caution – which Clanahan passes over in silence – was also dictated by the shortcomings of the video feed: ‘With the tools we are given,’ the primary screener told McHale, ‘there is only so much analysis we can do’ (p. 1396). I return to these limitations below.

[35] Six months earlier Time had featured an online report by Mark Thompson on Predator operations at Creech headlined ‘A new kind of Top Gunfor a new kind of war’: 5 October 2009; the reference was to the 1986 film starring Tom Cruise as a US Navy fighter pilot. But McHale’s claim was prompted by a statement from the Safety Observer, a senior pilot at Creech called in during the closing minutes of the engagement, who testified that ‘everyone around here, it’s like Top Gun, everyone has the desire to … employ weapons against the enemy’ (p. 1456).

[36] McHale’s recommendation to McChrystal did trigger a second (more limited) USAF investigation convened by the commander of the 432nd Air Expeditionary Wing and carried out by Brig Gen Robert Otto: ‘Commander-Directed Operational Assessment on Remotely Piloted Aircraft and Distributed Common Ground System Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures arising from Uruzgan province CIVCAS, 21 February 2010’, (10 July 2010); only 5 of its 38 pages (identified as Otto’s ‘Statement of Opinion’) were authorized for public release. The table of contents shows that 16 (wholly redacted) pages were devoted to ‘Predator mission conduct’, which was determined to be ‘a factor’ in the incident. But Otto’s summary statement challenged McHale’s criticism of the Predator crew. He dismissed the Top Gun jibe and found ‘no resemblance to a “Top Gun” mentality’ (p. 35). Otto conceded that the Predator crew’s ‘faulty communications clouded the picture’ but insisted that their actions were otherwise entirely professional and emphatically did not display ‘an inappropriate bias to go kinetic’ (p. 35).

[37] Human Rights Watch,‘Troops in Contact’: Airstrikes and civilian deaths in Afghanistan (2008).

[38] The files are available online at US Central Command’s FOIA Library at https://www3.centcom.mil/foia_rr/foia_rr.asp (under <5 USC 552(a)(2)(D)Records>); at ACLU’s website: https://www.aclu.org/drone-foia-department-defense-uruzgan-investigation-documents; and via archive.org. All my unattributed page references are to these files.

[39] The 65-page transcript in the Los Angeles Times starts at 0453 local time, but the transcript contained in the consolidated files of the investigation released under the FOIA does not start until 0714 and runs to only 36 pages (pp. 1951-1986); the preceding pages presumably remained classified, although 25 pages are duplicated so the omission may be the result of poor collation rather than redaction. Where the two transcripts overlap, they have been redacted differently. The reasons for the differences are obscure, but the transcript was evidently released in two versions. The provenance of the Times transcript (labelled ‘Tab E’) remains unclear; the newspaper credited the US Air Force, but US Central Command (which released the redacted version to the ACLU) told me that they had not released that version, the Air Force confirmed that it had not released it either, and its FOIA Library records only David Cloud’s request for the USAF (not US Army) investigation, which was closed out on 18 March 2011 – one month after the Times published his main article. Yet the transcript on which Cloud relied for his report, and which was published in the Times, has been redacted so – even if the attribution to the USAF was designed to protect a source – that version presumably was cleared for release at some stage. Unless otherwise noted, all timed observations in my text are from the Times transcript.

[40] One press report described the shock of officers at ISAF headquarters in Kabul who subsequently viewed the video feed from the Predator: ‘It was clear from the tape that civilians were about to be rocketed. “You look at the tape, you see the people getting in and out of the vehicles, and there’s really not a lot of ambiguity that you’re seeing women and probably children,” one officer said. “You’re not looking at men with weapons”’: Alan Cullison and Matthew Rosenberg, ‘Afghan deaths spur US reprimands’, Wall Street Journal, 31 May 2010. I wonder about this claim. On the evening of 21 February McChrystal showed the video to Brig Gen Edward Reeder (the commander of Combined Forces Special Operations Component Command) in Kabul – he had already seen at least part of it himself – and Reeder watched 40 minutes of the feed with Rear Adm Greg Smith (ISAF’s Director of Communications): ‘On the post-strike monitoring,’ Reeder testified, ‘I saw burqas and children…’ (pp. 1189-90; my emphasis). The weight of evidence from other observers in the hours before the engagement makes it clear how difficult it was to detect women from the video feed, but if that press report is correct the presumptive clarity – the lack of ambiguity – of those officers’ identification must have derived at least in part from the fact that they already knewthat women and children had been injured in the strike.

[41] The sensor operator who was on shift for most of the night and into the early morning had a scheduled break from 0830 to 0930 – a period which included the strike on the vehicles – and s/he was relieved by another sensor operator.

[42] That said, the former is far more likely: both sensor operators were USAF technical sergeants, and the two anonymised lists of interviewees included in the consolidated file show only one technical sergeant (the JTAC) (p. 1063; cf. pp. 490-1).

[43] It may be that McHale simply ran out of time. He asked McChrystal for an extension from 8 March to 24 March to enable his team to draft summaries of all the witness statements (more than 53 of them) and ‘to interview at least one other witness’ (p. 17), but the file records only one re-interview (p. 130) and interviews with the ‘Predator Piloting Team’ were completed by 5 March (p. 68). The sensor operators were on the original list of interviewees agreed with the commanding officer of the 15th Reconnaissance Squadron but on 4 March he raised a number of scheduling difficulties in making them available. They were ‘scattered over a couple of shifts’ and McHale was told it would take 48 hours to arrange cover (p. 894). McHale’s team did not interview the third member of the Predator crew either, the Mission Intelligence Coordinator (MC) who was responsible for online text messaging (mIRC) and for liaising with SOTF-South at Kandahar and with the screeners in Florida. S/he sat in the Operations Center outside the Ground Control Station at Creech but was an integral member of the crew and participated fully in the mission.

[44] The Fires Officer at SOTF-South explained that ‘the majority of our co-ordinations are done on the phone or on mIRC chat’ (p. 720); see also US Army FM 6-02.73, Tactical Chat (July 2009); ‘Tactical chat: how the US military uses IRC to wage war’, Public Intelligence, 22 January 2013. The importance of mIRC to the US military can also be judged by the ‘Afghan War Diaries’ released by Wikileaks, which included over 35,000 pages of mIRC transcripts: https://wardiaries.wikileaks.org.

[45] Ben Emmerson QC, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Counter-terrorism, praised the McHale report as ‘a model of accountability and transparency’: Report, 10 March 2014: 10 (A/HRC/25/59). It was a marked departure from the investigation into the Azizabad attack, which was widely criticised as inadequate – Human Rights Watch described Brig Gen Michael Callan’s report as ‘deeply flawed’ : Report, 15 January 2009 – and the release of the consolidated file a complete contrast to the investigation into the Kunduz attack, where the details remained classified – despite promises to the contrary – and ISAF even refused to cooperate with the Bundestag’s official investigation into the incident.

[46] Cockburn, Kill Chain, p. 14. To complicate the time-line still further, Creech Air Force Base is in the US military’s Uniform time zone, 8 hours behind its Zulu time (GMT/UTC) – the time recorded in the communications transcripts – and Afghanistan is in its Delta time zone, 4 hours ahead of Zulu; local time in Afghanistan is 4 ½ hours ahead of GMT/UTC. In order to fix the narrative I have converted all times to local time in Afghanistan. I have also corrected a number of the report’s phonetic transcriptions, and done my best to work around the redactions (some redacted passages appear elsewhere in the consolidated files en clair).

Pingback: Under Afghan Skies (3) | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Under Afghan Skies (2) | geographical imaginations

Pingback: Derek Gregory, Under Afghan Skies – Prologue and Part I | Progressive Geographies