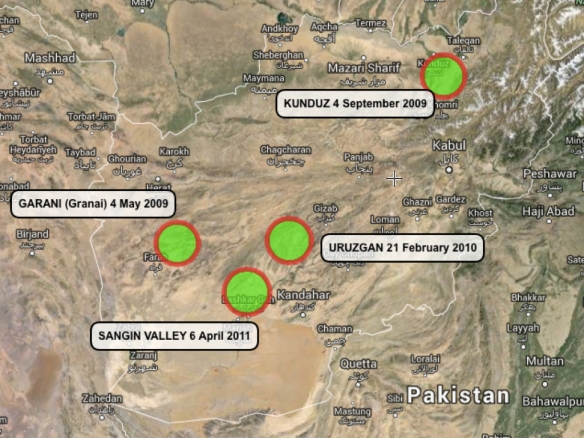

Here is the third installment of my essay on an airstrike on three vehicles in Uruzgan, Afghanistan on 21 February 2010 that has become one of the central examples in critical discussions of remote warfare. The first installment is here and the second is here. The background to the essay is here. And to be clear: many of the images I’ve used in this and the previous posts are taken from my conference presentation; some relate directly to this incident but others (as I hope will be obvious) are intended to be illustrative and do not portray the engagement under analysis.

***

0530

At 0531 the commander of the AC-130 warned that ‘we are right at the outer limit of our fuel’ and could only remain on station for another five minutes at most without a fire mission – and, like the JTAC, he plainly wanted one [101] – but the GFC decided that the distance was still too great so they would have to wait and ‘let things unfold.’ ‘We really need PID,’ the JTAC emphasised, ‘to start dropping.’

At 0534 the AC-130 reluctantly signed off. ‘We knew that as soon as we left they would be in greater danger,’ the commander told McHale (p. 1420). ‘Stay safe,’ he radioed the JTAC, and ‘we will try to send one of ours back out here for you tomorrow night.’ It was now down to the Predator. ‘All right,’ the pilot told his crew, ‘so it’s us.’

By then, alarm bells were also ringing at the Special Operations Wing at Hurlburt Field in Florida where the screeners had been following the vehicles. The Mission Operations Commander there ‘started beefing up the crew’ and ‘doubled up every position’ (p. 588). To increase the number of screeners was unusual, his commanding officer explained, but tracking two and eventually three vehicles and dozens of people needed ‘more eyes on the mission’ (p. 1412). It was a wise move, but it could do nothing to increase their chronically narrow field of view.

As the situation developed, it gained interpretive momentum, shaded by increasingly ominous exchanges between the Predator crew and the JTAC. These were reinforced by comments from the Afghan forces who accompanied the US Special Forces in Khod. ‘If the Afghans see something that I don’t see because some of them had [local] knowledge,’ the ODA’s second-in-command told McHale, ‘they’ll let me know’, and as soon as his interpreter translated it he would put it out over the inter-team net to keep everyone in the loop. ‘They were like nobody comes down from there at night with lights on,’ he explained, ‘announcing their presence. They told us that [the vehicles] were coming in to reinforce here because they had seen in the past stuff like that.’ The upshot was that ‘we just felt like they were coming for us’, and as the night wore on that impression ‘kept on building, and building, and building’ (p. 1569).

At Creech the sensor operator had zoomed in to focus the Predator’s infra-red camera on the passengers travelling in the back of the pick-up, and commented that it was ‘weird how they all have a cold spot on their chest.’ ‘It’s what they’ve been doing here lately,’ the pilot told him, ‘they wrap their [shit] up in their man dresses so you can’t PID it.’ The slur about traditional Afghan attire, the shalwar kameez, should not distract from the implication that the failure to identify weapons was suspicious in itself, not an indication of innocence at all but evidence of a deliberate strategy to conceal weapons from their surveillant eye. [102] So far the Predator crew had identified the people in their field of view as ‘individuals’, ‘passengers’ and ‘guys’, but their vocabulary became overtly prejudicial as they routinely referred to them as ‘MAMS’: ‘Military-Age Males’. [103] The term is redolent of what Jamie Allinson identified as a necropolitical logic which mandates that all those assigned to this category ‘pose a lethal threat to be met with equally lethal violence.’ [104]

The switch to ‘MAMs’ was triggered at 0534 when the pilot and the sensor operator both thought they saw one of the men carrying a rifle and the sensor operator read out a mIRC message from the screeners calling ‘a possible weapon on the MAM mounted in the back of the truck.’ The pilot lost no time in sharing the sighting with the commander of the AC-130, who was about to sign off, and with the JTAC: ‘From our DGS, the MAM that just mounted the back of the Hilux had a possible weapon, read back possible rifle.’

But almost immediately the search for weapons and the age of the people collided as the screeners sent a stream of mIRC messages that were less well received by the Predator crew. At 0536 they called ‘at least one child near [the] SUV’, and at 0537 they reported that ‘the child was assisting the MAMs loading the SUV’ (p. 1154). When the MC read out these calls there was immediate pushback. ‘Bull[shit],’ the sensor operator exclaimed, ‘where?’ ‘I don’t think they have kids out at this hour’, he continued, ‘I know they’re shady, but come on…’ The pilot looked over at the mIRC window and reinforced their presumptive ‘shadiness’: ‘[Assisting] the MAM, uh, that means he’s guilty.’ This was an open invitation to revise the age of the child upwards. ‘Maybe a teenager,’ the sensor operator grudgingly conceded, ‘but I haven’t seen anything that looked that short.’ The MC reported the screeners were reviewing. ‘Yeah, review that [shit]’,’ the pilot replied. ‘Why didn’t he say possible child?’ he fumed. ‘Why are they so quick to call [fucking] kids but not to call a [fucking] rifle?’ The next mIRC message did nothing to settle him; at 0538 the screeners reported not one but ‘two children are at the red SUV… Don’t see any children at the pick-up’ (p. 1154). Reading out their message the MC added his own rider: ‘I haven’t seen two children.’ Still, the pilot passed the call to the JTAC at 0538: ‘Our DGS is calling possible rifle in the Hilux and two possible children in the SUV.’ He seemed to have granted his own wish and turned ‘children’ into ‘possible children’. [105] (He later told McHale that ‘if the screener calls something and we are not sure we would tell the JTAC we had a possible….’ (p. 908)). The JTAC acknowledged the pilot’s relay and repeated that ‘[the] Ground Force Commander’s intent is to monitor the situation, to keep tracking them and bring them in as close as we can [to Khod] until we also have CCA [Close Combat Attack] up and we want to take out the whole lot of them.’ The sensor operator was still grumbling about the screeners – ‘I really doubt that children call,’ he muttered, ‘I really fucking hate that’ [106] – when at 0539 the MC said he had been told to remind him ‘in case they do get a clear hostile, and they’re children, to remove our metadata so they can get a snap of it.’ [107] Then he added, ‘But I haven’t seen a kid yet, so…’ At 0540 the screeners came back to report ‘One man assisted child into the rear of the SUV’ (p. 1154), which prompted the MC to ask: ‘Is this the child entering the rear of the SUV?’ As they watched their screens the occupants were all getting back into the vehicles, when they detected what they took to be a scuffle in the back of the Hilux. It is impossible to know whether this was a (re)interpretation of the previous message, but they evidently saw it as an altercation rather than ‘assistance’. ‘They just threw somebody in the back of that truck,’ the pilot claimed, while to the sensor operator it looked as though ’those two dudes [were] wrestling,’ and without consulting the screeners the pilot radioed the JTAC at 0541 to say that they had witnessed the ‘potential use of human shields’. [108]

All of these calls were at best circumstantial, and the evidential basis for most of them was exceptionally thin, but it was enough for the GFC to take pre-emptive action and initiate the call for more air support: and he wanted Close Combat Attack (CCA). The Predator had only one AGM-114 Hellfire laser-guided missile left in its rack – the other had been fired earlier in its flight – and that would not be enough firepower to engage all three vehicles. ‘I don’t think he’s gonna let us shoot,’ the pilot observed, ‘cause they wanna get all these guys – but still…’ The sensor operator wondered ‘who the next available CCA is gonna be’, because they might be able co-ordinate with them: ‘We’re gonna take this vehicle…’ While they were talking the GFC contacted SOTF-South’s Operations Center at Kandahar Air Field by satellite phone and asked for an ‘AirTIC’ to be declared. TIC stood for ‘Troops in Contact’ and immediately triggered aircraft to come to the aid of ground forces who were exchanging fire with the Taliban; the average response time in Afghanistan then was around 8-10 minutes. But an AirTIC was a purely precautionary measure intended to bring aircraft on station in anticipation of an engagement; it had no official status and was not part of established military doctrine but had become standard operating procedure for Special Forces. [109]

At 0545 the JTAC told the Predator pilot ‘we’ve opened an [AirTIC] and we’re going to get additional air assets on scene’. As expected, the GFC requested Close Combat Attack – helicopters – and not Close Air Support, and the Fires Officer at SOTF-South immediately contacted the Air Support Operations Center (ASOC) at Kabul, an Air Force unit attached to the Army to coordinate tactical air support (both CAS and CCA), which informed him that ‘the only thing they could get off the ground in a timely manner was a Scout Weapons Team’ (SWT) (p. 721). This consisted of two OH-58 Kiowa helicopters tasked for armed reconnaissance. [110] When the GFC called back to chase progress on his request, the Fires Officer told him the SWT would be coming, but added that it might be possible to bring in A-10 ‘Warthogs’ too, heavily armed gunships built around a high-speed 30mm rotary cannon that were often called on to support troops in contact because they had a long loiter time (compared to helicopters) and enhanced visibility of the ground (compared to other strike aircraft). The ASOC had already referred SOTF-South’s request for CCA back to Regional Command–South at Kandahar Air Field, and at 0541 its Duty Officer contacted the 82nd Combat Aviation Brigade (also at Kandahar Air Field) and authorised its Task Force Wolfpack – Alpha Troop from the 1st Squadron, 17th Cavalry Regiment – at FOB Ripley outside Tarin Kowt to launch two of its OH-58 helicopters to provide CCA in support of ‘a TIC’ 35 miles northwest of their base (p. 394); ‘AirTIC’ does not appear in the duty officer’s log.

Despite the live streaming of the FMV feed from the Predator onto a giant screen in SOTF-South’s Operations Center, the departure of the AC-130 leaving coalition forces exposed to Taliban attack, and the GFC’s declaration of an AirTIC to obtain additional air cover, the mission log at SOTF-South had fallen silent at 0536 with the transcription of a SALT report: ‘2-3 vehicles… [GFC] reports ISR [Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance: the Predator’s FMV feed] PID of 43-55 pax [people] in two groups carrying weapons’ (p. 1991). No further entries would be made for another two hours.

The responsibility for maintaining the log fell upon the officer designated as Night Battle Captain. [111] He usually monitored eight to ten operations at any one time, but Operation Noble Justice was the main mission that night. Ordinarily the role would have been filled by a major, but he had been seconded to assist with planning Operation Moshtarak in Helmand (p. 999). The captain who took his place had only been in post for three weeks, had received little training and was described by his own commanding officer as ‘barely adequate’ (p. 1103). [112] Yet all three remaining field-grade officers at SOTF-South were asleep, even though the night was the time of highest risk (pp. 1006-7), and apart from the Fires Officer – who arranged the additional air cover requested by the GFC – McHale noted that all the posts on the night shift ‘were filled by personnel who were significantly less experienced than the day shift counterparts’ (p. 51). While it was true that Operation Noble Justice could not be executed until dawn, the coalition forces were exposed to attack during the three hours they had to wait for first light. The GFC had made it clear that he thought the danger to them was increasing, but the green young battle captain merely monitored the stream of SALT reports through the small hours, acknowledging each one with a terse ‘Roger, Copy’ (p. 938), occasionally watching the Predator feed and periodically logging on to the mIRC chat: what McHale called ‘a pretty passive kind of watching’ (p. 1014). ‘I just monitored and saw what happened,’ the Night Battle Captain told him (p. 1549). [113] Although the major who was Director of the Operations Center conceded that the most active period was between 0200 and 0600 – the period with the ‘highest density of risk and threat’ – he insisted there were ‘wake-up criteria’ in place that were met in this instance and should have had him called into the Operations Center (p. 993). But he wasn’t. The Night Battle Captain said he ‘didn’t feel at that point it was necessary to wake anyone’ (p. 1549), and even as the situation deteriorated he still saw no reason to wake his senior officers or to reach down to the GFC. [114] A series of immensely consequential decisions would have to be taken by the GFC alone. [115]

The vehicles were now trying to ford a river, making several attempts to find a safe crossing. Their every move was being watched back in the United States and at 0551, when the water rose to the doors, the Predator pilot exclaimed: ‘I hope they fucking drown them out, man. Drown your [shit] out and wait to get shot.’ ‘I hope they get out and dry off,’ the MC added, ‘and show us all their weapons.’ The Predator crew was now anticipating an airstrike with relish, and they had a brief discussion about the legal envelope within which it would take place. The pilot wondered how the presence of ‘potential children and potential [human] shields’ would affect the application of the Rules of Engagement, and the sensor operator told him the GFC was assessing (or would have to assess: the basis for his comment is unclear) ‘proportionality and distinction’. That is confusing too – or perhaps just confused – since those are considerations required by International Humanitarian Law rather than the ROE. They forbid military force to be used against civilian targets or to cause ‘excessive civilian harm’. ‘Is that part of CDE [Collateral Damage Estimation]?’ the pilot asked, adding that he was ‘not worried from our standpoint so much’ – since that was not their responsibility – but that it was asking a lot of the GFC to make such a determination. The sensor operator thought he would have to wait ‘until they start firing, cause then it essentially puts any possible civilian casualties on the enemy.’ ‘If we’ve got friendlies taking effective fire,’ he said, ‘then we’ve gotta do what we’ve gotta do.’ Should that happen before the SWT arrived, the pilot decided, ‘we can take a shoot … get as many as we can that are hostile, hopefully track them still in the open’ – and then, presumably, talk the helicopters onto the target once they arrived.

The Predator crew clearly had no pre-strike guidance from a military lawyer from the Judge Advocate-General’s Corps (known as a JAG). By 2005 JAGs were part of the US Air Force’s ‘kill-chain’, stationed on the operations floor of CENTCOM’s Combined Air Operations Centre (CAOC) at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar to advise on targeting. [116] They were also forward deployed in Afghanistan, but the Safety Observer at Creech Air Force Base, who was called in shortly before the engagement and whose responsibilities included ‘making sure the ROE had been met’, confirmed that there was no JAG ‘on site to consult during these engagements’ (p. 1459). [117] In any case, the leading strike aircraft in this instance would be the OH-58 helicopters. As the Predator crew had realised, the onus was on the GFC, who had to decide whether the vehicles constituted a legitimate military target whose execution fell within the ROE and the Tactical Directive, and then order the JTAC to issue a ‘nine-line’ brief and clear the aircraft to engage. [118]

The Safety Observer explained that ‘the only other way’ a strike could be authorised would involve the identification of a High-Value Individual (HVI) whose execution would require an additional level of clearance through ‘a joint targeting message from the CAOC’ (p. 1457). [119] The GFC knew that – ‘an HVI was above my authority’ (p. 953) – and so did the JTAC, who said he would have had to refusd any order from the GFC to clear the helicopters to engage an HVI without higher approval (p. 1495). The JTAC told McHale that the GFC was still convinced that the convoy was carrying at least one HVI (p. 1491) – the ‘high-level Taliban commander’ and his security detail inferred at the start of the pursuit – but that he had also decided it posed an ‘imminent threat’ to coalition forces at Khod, which the JTAC was satisfied constituted sufficient grounds to engage (p. 1495).

It is impossible to adjudicate the issue: the GFC claimed that he had discounted the presence of an HVI (above, p. 00), and since the CAOC was not involved in cases of self-defence and imminent threat – the presumptive triggers in this instance – the only sources of legal advice available to the GFC were JAGs at the two Special Forces Operations Centers at Kandahar and Bagram Air Fields. Throughout the night neither was contacted by the battle captains.

0600

At 0601 Task Force Wolfpack’s Duty Officer at FOB Ripley logged the request sent via Regional Command–South ‘for aircraft coverage for [a] TIC’ (p. 402). McHale characterised this as a ‘911 call’ (p. 1438) which – whether he intended to or not – was a tacit acknowledgement that the narrative had been transformed and a precautionary measure had become an emergency response. This was exactly how the message was received by the helicopter crews, and in fact throughout the stream of communications that resulted in the Scout Weapons Team being scrambled the situation was consistently described not as an AirTIC but as a TIC: a live incident. Those charged with providing air support, as Air Force Lt Gen Stephen Hoog explained, ‘are not in the business of determining whether a TIC is “real” or not.’ [120]

Within ten minutes of the call being received at FOB Ripley the Predator crew knew that two OH-58 helicopters would be scrambled. All they could do for the moment was watch the vehicles on their screens and wait as their drivers made heavy weather of it (Figure 4). The dirt roads and uneven ground meant they rarely exceeded 10 m.p.h., and there were several stops for people to get off to help the vehicles make it up a steep incline. There were other stops, sometimes to let an overheated engine cool down and at others for punctures or repairs to the wheels (fortunately for them – though not for him – they had a mechanic with them). ‘When something breaks in Afghanistan it probably breaks pretty good,’ the MC observed, ‘with all the rough terrain and everything.’

From here on virtually everything the Predator crew described, in conjunction with the pilot’s exchanges with the JTAC, contributed to the continued collaborative construction of an imaginative geography of an impending Taliban attack. The fact that there were vehicles out there at all attracted suspicion. In such a poor area, the JTAC told McHale, ‘from my experience those with vehicles are well-off and supported by the Taliban or Taliban themselves’ (p. 1487). Soon the vehicles had become ‘technical trucks’ – a standard term for pick-up trucks with improvised mounts for crew-served weapons [121] – and when they were joined by a third at 0602 (dubbed ’guilt by association’) this was seen as a ‘grouping of forces’ and now they constituted a ‘convoy’. At 0617, after they had finally crossed the river and stopped for people to get out and pray – the Fajr that was a normal start to the day for any devout Muslim – this was seized upon as a Taliban signifier: ‘They’re praying, they’re praying,’ the sensor operator declared, ‘I mean, seriously, that’s what they [the Taliban] do.’ The MC agreed: ‘They’re gonna do something nefarious.’ [122] This was the moment when the passengers in the vehicles first became aware of an aircraft:

‘There is a rest area on the way where we stopped to pray,’ explained one of the women. ‘We got out of our cars, men and women. After our prayer, we left. That’s when we heard the sound of a plane. But we couldn’t see it.’ [123]

But it could see them, and a couple of minutes later the MC directed the crew’s attention to ‘that [infra-red] spot in the back of that truck.’ ‘It’s all their guns,’ the sensor operator told him. This too was a leap of (bad) faith, followed by yet another. When the MC passed the screeners’ identification of an adolescent near the rear of the SUV, the sensor operator responded with ‘teenagers can fight’, which the MC amplified: ‘Pick up a weapon and you’re a combatant, that’s how it works’ (it isn’t). Once the screeners identified an additional weapon, the pilot was evidently satisfied that they were now on the same page as him and his crew: ‘I’ll make a radio call,’ he said on the intercom, ‘and I’ll look over [at mIRC] and they will have said the same thing…’ This was not the screeners’ view – to the contrary –but it served to enrol them in the crew’s elaboration of their narrative. It also reversed the inferential order, since the role of the screeners was to pass expert calls to the Predator crew for transmission to the GFC rather than act as secondary confirmation.

In the midst of this cascade of mutually reinforcing interpretations, the GFC continued to exhibit what – following McChrystal’s guidance – McHale praised as ’tactical patience’. When the vehicles stopped for the dawn prayer they were six or seven km (four miles) from the nearest coalition forces, and at 0627 the JTAC explained that the GFC still planned ‘to let the situation develop, permit the enemy to close [on coalition forces at Khod], and we’ll engage them closer, once they’ve all consolidated.’

By then the helicopters were on their way. The two aircrews that made up Scout Weapons Team 1 (SWT1) had reported for duty at FOB Ripley at 0600 and anticipated carrying out routine armed reconnaissance along what coalition forces called Route Bear, the dirt highway that wound 160 miles south from Tarin Kowt to Kandahar. Ordinarily they would have been airborne between 0700 and 0800, but the lieutenant in command of the team explained that as soon as they arrived for their overnight intelligence (ONI) briefing they were ‘notified that the ground force operating north of Cobra [FB Tinsley] had declared a TIC’ (p. 776), and the pilot flying trail said that they ‘got freaked’ and scrambled more or less immediately at 0615 (p. 1438). The OH-58s did not have to be readied, and one journalist who visited Ripley saw them sitting ‘in their concrete blast bunkers on the dispersal ramp, fully fuelled and armed and ready to go 24 hours a day.’[124]

The two pilots flying that day rushed to complete the paperwork and ran up the engines, while their co-pilots (the ‘left-seaters’) stayed to receive detailed information. As he waited for the lieutenant to join him, the pilot flying lead contacted the JTAC who ‘painted a very broad picture for me’ (pp. 513-4). Shortly after take-off at 0630 the lieutenant (call sign BAMBAM41) radioed that they were en route

‘responding to a TIC [redacted] reporting 2-3 technical trucks with heavy weapons, 35-50 Taliban maneuvering on their positions. [ICOM] suggests the Taliban think they can overrun friendly forces…’ (p. 336). [125]

The helicopters at Ripley frequently responded to TICs but the familiarity did nothing to diminish the sense of urgency. The lieutenant testified that it was ‘the norm rather than the exception’ for the Special Forces at FB Tinsley ‘to get into TICs when they go outside the wire’ (p. 777). The aircrews had worked with ODA 3124 before and knew them ‘very well’, and the pilot flying lead believed that they were ‘about to get rolled, and I wanted to go and help them out… There was a 12-man team out here plus whatever [unintelligible] they had that were about to get a whole lot [of] guys in their faces’ (p. 516). Yet again there was no indication that their mission was a precautionary measure; to the contrary. [126]

As they approached their holding position south of FB Tinsley – they would subsequently land at Tinsley to conserve fuel, fly back to Tarin Kowt to refuel and then return to Tinsley and flat pitch (pp. 408-9) – the crews attempted to familiarise themselves with the situation. Like ODA 3124 they had an unambiguous sense of the area as a threat landscape. The map from their ONI briefing was peppered with ‘IED hotspots’ and ‘IED cells’, ‘insurgent spotter locations’ and ‘insurgent spotter networks’, ‘insurgent fighting positions’ and ‘insurgent activity’ which, according to the summary, had increased markedly over the past month (p. 372) (Figure 5). [127]

This was another, intensely visual modality of areal essentialism (above, p. 00), which must have been reinforced by the crews’ experience of providing support to ground forces (‘we respond to a lot of TICs’: p. 777). As they flew towards the firebase they picked up radio communications between the JTAC and other aircraft, including the Predator, which helped to animate their map, and while they had no access to the Predator’s FMV feed they were able to plot the progress of the vehicles and put the operational picture together.

The JTAC warned the helicopter crews not to ‘burn the target’ – alert the occupants of the vehicles – but to hold south of their position ‘out of earshot’ to give them time to ‘consolidate on our location’ before moving in to strike, at which point he said the GFC’s intent was ‘to destroy those vehicles and all the personnel with them’ (p. 336). At 0641 the Predator pilot relayed a message to the JTAC from SOTF-South advising him that, as promised, other aircraft were ‘being pushed to this as well’ (call sign DUDE). When the Fires Officer had told the GFC that A-10s might be coming too, he had been asked to have them hold south of the grid – like the helicopters – so that the occupants of the vehicles would have no warning of an attack, and the Predator pilot now relayed that DUDE was currently holding south of FB Tinsley and could be on station in four minutes. At 0645 the MC noted that the information about the TIC had finally appeared in the ASOC chat room (‘TIC A01’), and at 0649 the pilot was asked to bring the Predator down to 13,000 feet to de-conflict the airspace: ‘Have DUDE above you in support of TIC A01.’

But this was not the keenly anticipated A-10s. Instead two F-15Es roared overhead. The F-15 was originally designed for aerial combat, not CAS and still less CCA. Although the F-15E had been modified to conduct bombing missions, it flew at speeds that could exceed Mach 2.5 (around 3,000 km/hr) and so its pilots were wholly dependent on its sensors for target identification and laser designation. This was noisy, split-second stuff, and the GFC was furious. He immediately made another satellite phone call to the Night Battle Captain at SOTF-South: ‘I was very adamant. I have fast-movers over my station, my desire is to have rotary wing aircraft’ because ‘they can PID any type of individual much better than some[one] flying at 15,000 feet dropping a bomb’ (p. 940). [128] The advantage of the helicopter – the capacity to come in low and slow – was supposed to be compounded by the persistent presence of the Predator. The commander of the 432ndAir Expeditionary Wing boasted that his Predators ‘don’t show up on the battlespace and have 15 minutes of hold time to build our situational awareness. We have a high capacity to make sure that we have the exact, right target in our crosshairs…. Time is not our enemy. We own time.’ [129]

In this case, even though the Predator was on station for more than three hours before the engagement, they didn’t. And it was a matter of space as well as time. The GFC believed that the roar of the jets overhead had burned the target, because as soon as the F-15s made their pass the three vehicles changed direction; instead of heading south they were now driving along a ridge to the west (Figure 6). [130] At 0655 the JTAC told the Predator pilot that when the F-15s appeared ‘everyone started talking [on ICOM] about stopping movement.’ The occupants of the vehicles were now caught in a trap: all the time they were heading towards Khod they were seen as posing a direct threat, but as soon as they turned away many of those following their progress assumed they were executing a flanking manoeuvre.

That possibility was raised by the JTAC at 0708 – ‘it appears that they’re either trying to flank us or they’re continuing to the west to avoid contact,’ he told the Predator pilot, and asked to be warned ‘if those vehicles turn south’ (his emphasis) – and the Predator pilot replied that his crew ‘can’t tell yet if they’re flanking or just trying to get out of the area.’ The sensor operator thought ‘they’d go back home if they were trying to get out’, and during his interview with McHale’s team the JTAC said much the same. Asked ‘Is there anything this convoy could have done that would have prevented this engagement?’ he shot back: ‘travelled north’ (pp. 1496-7).

‘Flanking’ was a loaded term – one of the key lessons learned from this incident and incorporated into the Army’s guidance was that language like ‘”flanking” can lead to assumptions regarding hostile intent that may be unfounded’ [131] – but the die was soon cast. For the next hour or more the Predator crew considered every possible route the vehicles could take to bring them down to Khod. At 0708 the MC thought they were ‘trying to go around this ridge’, and the sensor operator pointed to ‘some low ground here, like a valley that goes straight to the village, it looks like…’ He added that he ‘wouldn’t be surprised if they started heading south-east at some point’ (towards Khod).

Watching from Hurlburt Field, the screeners doubted the flanking call and did their best to close it down. The primary screener had been following the FMV feed and, with her geospatial analyst, tracking the vehicles on Falcon View, a digital mapping system. At 0710 she discussed their movement with one of her FMV analysts: their assessment was that ‘rather than moving south [they] appeared to be moving west out of the area’ (p. 1407). She had no direct communication with the JTAC but she immediately sent a message to the Predator crew via mIRC saying it ‘looks like they are evading the area’. In reply, the MC told her they ‘may be flanking, too soon to tell right now.’ She was still convinced the vehicles had ‘continued past all of the roads that they could have turned and been about to flank blue [coalition] forces’, so she sent a second, urgent mIRC message: ‘too far away from blue forces to be flanking.’ The response from the MC was dismissive – ‘They were spooked earlier from [the F-15s]’ (p. 1392) – and the same FMV analyst complained to McHale that the Predator crew ‘were very quick to disregard our assessments…. The MC comes up and tries to convince us that this is hostile forces. Their desire to engage targets gets in the way on their assessments’ (p. 1408).

The Predator pilot had a different interpretation of what took place. In his eyes pursuing the possibility that the vehicles were flanking was ‘the most conservative call’. One of McHale’s team raised his eyebrows at that; as a former brigade commander he took ‘conservative’ to mean ‘I don’t fire’. But the pilot stuck to his guns. To him a conservative call was about ‘keeping our guys on the ground safe’, and he was unwilling to make ‘any hasty calls’ about the vehicles evading the area. He elected to make what he believed were ‘the safest calls for our guys on the ground’ (p. 915).

Perhaps for that reason, the primary screener’s interpretation was never passed to the JTAC (p. 22). [132] Her immediate superior, the Mission Operation Commander at Hurlburt Field, told McHale that ‘the biggest wild card is what these guys [the Predator crew] are telling the dudes on the ground’ (p. 594) – and what they were not [133]– and the screeners had no access to that information. Their only points of contact were via mIRC with the MC at Creech and with the Operations Center at SOTF–South.

The Predator crew remained alert for every possible route that would take the vehicles down to Khod. At 0716 the JTAC asked for an update on their position and direction of travel, and – following the sensor operator’s suggestion – the pilot told him ‘we’re coming up on a valley here, so we’ll be able to tell if they’re turning south towards you…’ A few minutes later he told the crew: ‘Does kinda look like he’s turning south here, huh, maybe? No? (Expletive) I can’t tell!’ Throughout these and subsequent exchanges the will of the Predator crew to have the vehicles turn south was almost palpable, which would (in their eyes) have validated the strike to which they were now committed: ‘Still a sweet fucking target,’ exclaimed the sensor operator.

At 0719 the MC raised the possibility that the vehicles were leaving the area, though only on the crew intercom and without mentioning that this was the screeners’ assessment – ‘They could[‘ve] got spooked earlier and called it off’ – only to discard it as soon as the pilot again asked: ‘They are turning south, huh?’ The MC immediately agreed, pointing to a road, and the pilot radioed the JTAC: ‘It looks like the road we are following currently trending to the south, so back to the south at this time…’ He estimated the vehicles were now around six nautical miles (11 km) from the nearest coalition forces at Khod. And yet doubts continued to surface; this was a difficult landscape to read from 14,000 feet. ‘I really don’t know, man,’ the pilot confessed at 0722. Would they ‘take this valley to the south and run? Or if they’re going to go back towards our guys, or what?’ A few minutes later the sensor reassured him. In a mile or so ‘they might have a chance to turn east. I think there’s a road that cuts through these ridges…’

They had to wait for confirmation because all three vehicles juddered to a halt for more repairs. At first it appeared to be just another puncture, but as the delay dragged on it seemed to be more serious. One of the men appeared to have crawled under the Hilux to work on its suspension, so the Predator crew concluded they had hit something when they forded the river. ‘You gotta pretty much know how to fix a vehicle if you live in Afghanistan,’ the MC would observe later on. ‘When something breaks in Afghanistan, it probably breaks pretty good.’

0730

While the vehicles were at a standstill – they would not be able to resume their journey for another half hour or more – the screeners were asked about the demographic composition of the occupants, and this time the pilot did pass their assessment to the JTAC: ’21 MAMs, no females, two possible children.’ ‘When we say children,’ the JTAC asked, ‘are we talking teenagers or toddlers?’ Without consulting the screeners the sensor operator advised the pilot they looked to be about 12, ‘more adolescents or teens’, and he agreed: ‘We’re thinking early teens,’ he told the JTAC. The screeners confirmed but then updated their call. ‘Only one adolescent,’ the pilot radioed the JTAC, who replied that ‘12-13 years old with a weapon is just as dangerous.’ McHale was repeatedly told that age had a different meaning in Afghanistan. The GFC explained that the Afghan forces with whom they worked included fighters as young as 12 – ‘if they can carry a gun, they will fight’ – and that the definitions of adolescent ‘for Americans versus Afghans are completely different’ (p. 943). To the JTAC an adolescent was ‘someone that is 15 years old, a young adult. We have [Afghan National Army], [Afghan National Police] and [Afghan Security Guards] that work with us, and they are teenagers. They are not 15 years old by American standards. I’ve seen them be fairly cold-blooded on the battlefield and I know that the insurgent forces have a lot of young men working for them, supporting the Taliban’ (p. 1484). In his view a ‘military-age male’ could even be ‘as young as 13 years old’ (p. 1485). These are instructive glosses because they accentuate the differences between Afghan and American culture – one of the mistakes of the cultural turn described by US counterinsurgency doctrine was its failure to acknowledge co-incident similarities between American and other cultures, which I suspect made empathy all the more difficult to achieve – and because the key differences are those that can be read as prejudicial and ultimately hostile.

By now the Predator crew had become so convinced by the subtitles they had been adding to the silent movie playing on their screens that they were turning negatives into positives. The absence of rifles when the passengers got out was explained away – ‘They probably mostly left their weapons in the vehicles’ – and when the JTAC told them he was looking for more than AK-47s, ‘something like a mortar, or something large and fairly obvious’, the pilot promised ‘we’ll keep our eyes open but we haven’t seen it yet.’ That dangling ‘yet’ was pregnant with meaning, and a few minutes later the Predator crew speculated that there could be a dismantled mortar in the back of one of the SUVs and that the passengers might be sitting on the mortar tubes or they could be concealed ‘anywhere in [the] base plate.’ It is a truism that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence – but it is certainly not evidence of presence.

As they attempted to obtain a clearer view, with the sensor operator adjusting the focus of the cameras and then switching from infra-red to full colour imagery as the sun came up, they looked forward to the airstrike they were convinced was coming. They knew the helicopters would be responsible for attacking the vehicles so the pilot explained they would have to ‘play squirter patrol’ and go after those who escaped from the wreckage. ‘I imagine they’ll run like hell all over the place,’ the sensor operator reflected, and if that happened the pilot told him to ‘follow whoever gives you the best shot and ends with us shooting.’

Meanwhile, in addition to evaluating ICOM and the reports from the Predator crew via the JTAC, the GFC continued to direct ground operations at Khod. As soon as dawn broke his teams had been good to go, and they had been busy carrying out searches, busting locks with bolt-cutters – an electronics store was of particular interest because it was the suspected source of components used for making radio-controlled IEDs – interrogating suspects and taking biometrics (p. 948). In two hours they had detained 70 men for questioning (p. 1356).

As these operations in the air and on the ground continued, Creech and Khod both alive with activity, SOTF-South’s Operation Center at Kandahar Air Field came to life too. It was arranged in tiers of half-moon seats, the lights dimmed, all eyes focused on the displays at their individual workstations, those on duty glancing from time to time at three 10 X 12 screens above their heads showing the FMV feed from the Predator and the route of the convoy on Google Earth and Falcon View. At the very top and centre – ‘the centre of gravity’, as Petit described it to me – sat the battle captain who had been monitoring events throughout the night. At 0735 the shift changed, and when the Day Battle Captain arrived he found the Night Battle Captain, his operations NCO and the Fires Officer all ‘fixated on … the big screen, watching our Predator feed’ (p. 1224). He was quickly briefed on the developing situation by the Night Battle Captain, who gave him transcripts of the SALT reports, reviewed the route of the three vehicles and explained that they were ‘potentially responding to [an] enemy commander’s call to muster forces and maneuvering to attack’ (p. 2107). He also told him about the reported sightings of children (‘one or two kids’) and weapons (p. 1226).

It took the Day Battle Captain 15-20 minutes to get up to speed. He was a former ODA commander, and although he had only deployed with SOTF-South the previous month he had been trained for his role since September and was both more experienced and more assured than his predecessor. He knew ODA 3124 and the area in which they were operating – ‘They have a very good idea of situational awareness… they know the terrain and they know the enemy’ (p. 1225) – and he had no hesitation in accepting that the occupants of the vehicles were probably hostile and that the GFC had good reason to think the Taliban were gathering for an attack on his position. He also knew that the Scout Weapons Team had been scrambled in response to the AirTIC, but – in his eyes and those of his colleagues at SOTF-South – this remained a precautionary measure and, unlike a TIC, did not trigger any battle drill in the Operations Center.[134] He knew too that the OH-58s were currently off station refuelling, and he also understood that the GFC wanted to wait in order ‘to allow the enemy to come in’ close to Khod (p. 1233). All told, he had no reason to suppose an airstrike was going to happen any time soon. But neither did he think a ground attack was imminent. Like the screeners he could see from the Predator feed and from the digital map displays that the vehicles had changed direction and were now moving away from Khod. He opened his folder containing the Tactical Directive to work out ‘at what point, if those forces needed to, they could … potentially call fire from any of those assets [aircraft] that were on station.’ He was unsure – he had never seen an airstrike called in such a situation before (p. 1241) – and so he went to get SOTF-South’s JAG (‘someone who was extremely smart with the Tactical Directive’) to ‘help us to review what we are seeing and to put it into his own eyes’ (p. 1228) so they could advise the GFC ‘the next time we were in contact’ (p. 1254). This in itself was unusual: the military lawyer was ordinarily called only once a battle drill had been initiated – following the declaration of a TIC, for example – and where ‘there [were] civilian casualties as a result from [a] kinetic strike’ (p. 1227). But in this case only an AirTIC had been declared and no battle drill had been initiated.

The JAG, Capt Brad Cowan, was new to Afghanistan – he had deployed in January fresh from the 1st Special Forces home base at Fort Lewis near Tacoma – and also new to his role at SOTF-South. His previous front-line tour of duty had been with the US Army Trial Defense Service in Iraq in 2006-7, where his primary responsibility had been to represent soldiers at courts martial, boards and criminal investigations. The application of International Humanitarian Law, the ROE and the Tactical Directive required different skill sets. At Kandahar Cowan conducted legal scrutiny of all CONOPS, and although his targeting experience was limited – and he had been involved in only one incident involving civilian casualties, just two weeks earlier, the result not of an airstrike but of a combat patrol returning fire from a residential compound – he was commonly called to the Operations Center to advise on the use of air support and so he knew that there was little lead time for dynamic targeting. [135] One of the NCOs ran over to give him the mIRC printouts, which he read as he hurried to the Operations Center, and when he arrived shortly after 0800 he scanned the SALT reports, watched the Predator feed on one of the giant screens and jotted down notes on the Rules of Engagement and the Tactical Directive (p. 608).

Meanwhile Colonel Gus Benton, the commander of Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force – Afghanistan (CJSOTF-A) at Bagram Air Field, the link above Kandahar in the Special Forces chain of command, was heading over to his Operations Center. This was his fourth tour of duty in Afghanistan, and like all field-grade officers he had wake-up criteria but his staff had never had occasion to disturb him before (or perhaps never dared to). But early on that Sunday morning his Night Operations Chief had phoned to alert him to the developing situation with ODA 3124. ‘I was told we had [a] TIC’ (p. 527), he recalled, though he couldn’t remember ‘specifically what he told me, I just said “Roger, okay, got it”’ (p. 542). He got up and monitored radio traffic on his desktop receiver until he decided to dress and go over to the Operations Center. He did not wait for a briefing, he told McHale: ‘I just walked in and said “Have we dropped?”’ (p. 543). It was a characteristically blunt question but it did not elicit the answer he expected. CJSOTF-A’s JAG had not been called (he never was), but Benton’s deputy did his best to justify the GFC’s tactical patience. He was a former ODB commander who had served in Tarin Kowt in 2005-6 and had experience of similar situations, and he told Benton he thought the GFC was right to wait until the vehicles were within sight of Khod. ‘I said that is what we did, we let them come to us so we can get eyes on them,’ he told McHale. ‘During my time I never let my guys [in the ODAs] engage with [Close Air Support] if they couldn’t see [the target]. I said that is great and Colonel [Benton] said “that is not fucking great” and left the room’ (p. 758).

The two men had a fractious relationship, and his deputy was worried that Benton was going to call down to Kandahar and order a strike. True to form, at 0820 Benton contacted SOTF-South and demanded that its commanding officer be brought to the phone. The Day Battle Captain immediately went to fetch Petit. When he was woken up – he too had wake-up criteria but nobody had alerted him to what was happening – Petit was taken aback at the peremptory summons and frankly ‘ticked off’ that he had been brought in ‘so late in the game’ (p. 1085). The Day Battle Captain did his best to explain the bare bones of the situation as they hurried back to the Operations Center, but it took less than a minute and Petit was hardly well prepared when he picked up the phone. During their short and no doubt terse conversation Benton did not issue a direct order to strike the vehicles but to Petit his meaning and intent were unmistakeable: ‘his guidance was to put lethal fires on them’ (p. 1094) because he was convinced ‘this was a target that was right for an engagement’ (p. 1112).

In his own evidence, Benton said that he told Petit he wanted ‘to make sure we minimise collateral damage’:

‘Let’s not wait until those forces get on top of our guys to take it out. What I saw on the screen was vehicles, empty roads as the element [vehicles] moved, no villages or compounds in the direct vicinity. I thought as if I were pulling the trigger; a pattern like this maneuver, this JPEL moving along this road, no significant collateral damage. The conditions were right based on what I understood for an effective target’ (p. 530). [136]

The first part made sense. The Tactical Directive limited attacks against residential compounds in order to minimise civilian casualties, and by then the vehicles were in open country (‘empty roads, no villages or compounds’) heading through a wadi that the GFC described as a ‘rat-line’, a supply route used by the Taliban (p. 1360).

But the second part was more problematic. Benton endorsed the GFC’s early belief that a ‘High Value Individual’ (HVI) on the JPEL target list was among the passengers, though he later admitted he had no direct knowledge of one at all. In any case, he had other, more urgent reasons to want a strike. He was convinced that the vehicles and their occupants displayed a suspicious ‘pattern of life’ (a phrase he repeated several times) – that the vehicles were maneuvering tactically (’that pattern of maneuver’) – and that there was no time to waste.

Benton said he thought time was running out because coalition forces were ‘still prosecuting objective Khod’ and ‘the Pred feed [showed] vehicles moving to reinforce… getting closer….’ There was nothing complicated about it; unlike the Predator crew, and eventually the JTAC and the GFC, he did not debate whether the vehicles were evading or flanking because he was convinced they were still heading directly to Khod. When his Night Operations Chief woke him up he may have been told the distance from the convoy to coalition forces, he wasn’t sure, but given the time between that wake-up call and his arrival in the Operations Center Benton concluded that ‘obviously they have gotten closer, in my head they have gotten closer’ (p. 552). He made the same assertion multiple times (‘vehicles moving towards objective Khod’) until an exasperated colonel on McHale’s team pressed him on how he knew. Benton admitted he never consulted a map, but looking up at the Predator feed on the wall and ‘seeing the vehicles move towards the objective’ he decided he ‘needed to make the call to Lt Col [Petit].’ When he was asked to confirm the vehicles were still heading south, Benton blustered: ‘There [was] no way for me, Pred feed, vehicle moving on the road, to make that discernment, whether we are talking south or north…’ The colonel pointed out an icon in the lower left corner of the FMV feed that showed the direction of tracked movement. The vehicles were moving southwest not south. ‘Okay,’ Benton responded, ‘well I missed that’ (pp. 546-7).

But the colonel had not finished with him:

‘Now here’s why we are asking. If you go back over here [indicating the map], objective Khod, vehicles first identified and then throughout the morning, as you can see, initially moving in that direction. But then they are tracked all the way over here – there’s the objective. And then they continue off to the southwest, so we were a little surprised when you mentioned vehicles moving towards objective Khod… If that helps paint the picture’ (pp. 547-8).

‘I will take a hit on that,’ Benton responded – a remarkably insensitive choice of words in the circumstances – before rallying and defiantly asserting that distance did not matter to him: ‘I would have pulled the trigger on a dynamic target thousands of kilometres away…’ (p. 551). A Predator pilot might well do that – Creech was more than 11,000 km away – but not a commander on the ground. For one of McHale’s legal advisers reminded Benton that the Tactical Directive madedistance matter because it had a direct bearing on whether a target posed an immediate or imminent threat (p. 550).

Benton was not alone in his casual attitude towards geo-location. His Night Operations Chief told McHale that from the time they woke Benton until he walked into the Operations Center ‘nothing changed’ and they briefed him accordingly. And he too insisted that when the vehicles were hit they were closer to Khod than when they were first spotted. ‘It’s hard for me to stay in my seat,’ exclaimed one exasperated member of McHale’s team (maybe the same one). ‘It’s about 5½ kilometers when they start in the north and 15 kilometers [nine miles] when they got struck.’ ‘What’, he wanted to know, is ‘the responsibility of the Ops Director with situational awareness and understanding?’ (p. 1472).

It was a good question, because the calibration of distance involved more than reading the Predator feed correctly. As soon as Cowan arrived in the Operations Center at SOTF-South he had asked for ‘a straight-line distance between the team and the convoy’ precisely because he wanted to know whether the vehicles posed an imminent threat to coalition forces (p. 611). One of the NCOs measured it on a Google map overlay as 12.8 km (eight miles) (p. 604), but observers at different locations had different ideas about how that translated into time. The lieutenant commanding SWT1 thought it would have taken the vehicles ‘at least a couple of hours’ to reach Khod – which prompted one of McHale’s team to ask him ‘so what is “imminent threat” again?’ (p. 783) – while the pilot flying trail reckoned it would have taken them ‘three hours, give or take’ (p. 1441). But they had latterly picked up speed – at 0708 the Predator pilot reported they were ‘hauling pretty good’ and by 0717 they were travelling ‘faster than the past hour, fastest yet’ – and perhaps for this reason the Fires Officer at SOTF-South thought ‘it would have taken 35-45 minutes [for them] to get back to where the team was’ (p. 723), while the GFC believed they ‘would be on me in fifteen to twenty minutes’ (p. 980). Cowan provided no estimate of his own but given the distance he did not believe the vehicles constituted an immediate threat – though in the course of a protracted discussion with the senior legal adviser on McHale’s team he tied himself in knots, arguing that they did pose an ‘imminent threat’ before adding ‘imminent to me means immediate’ (p. 614) – and testified that in his view ‘at all times’ the vehicles met ‘the definition of imminent threat’ (p. 653).

Distance was also a key factor for others in the Operations Center at SOTF-South because – unlike Benton – they realised that the vehicles were now much further from Khod than when they had first been spotted. At the very least – again, in contrast to Benton’s harried urgency – they believed this bought them time. When Petit finished his call with Benton (he had simply listened to his superior and promised to call back after he had been briefed) he admitted he was in a state of ‘near panic’ (p. 1112). But he relaxed when he heard the vehicles were still so far from Khod: he told McHale ‘we felt like we had time’ to decide a course of action (p. 1113). The JAG stepped forward and gave Petit his legal opinion: there were insufficient grounds for an airstrike. Not only were the vehicles increasing their distance from coalition forces – moving away rather than closing – but also, and more importantly, they did not constitute a legitimate military target: ‘I didn’t see anything in that video feed that would indicate a hostile act or hostile intent’ (p. 610). [137] The likely presence of children also gave him pause. The resolution of the Predator feed was ‘fairly poor’, he said, so that ‘if someone was being identified [by the screeners] as a child through that view, then he must be fairly young… It must have been obvious that they weren’t a fighting-age male’ (p. 607). he absence of heavy weapons was another concern. He required evidence of ‘something more than just AK-47s,’ he explained, ‘which are not an indication of hostile intent. Everybody has a weapon in this country. Something bigger, something crew-served, some mortar system, a larger number of weapons, more than just a few ‘ (p. 613). [138] In sum, Cowan believed that in the circumstances ‘some sort of show of force or potential escalation of force’ (p. 604) would achieve the ‘same effect as engaging the target’ (p. 615) and unlike an airstrike would be consistent with the Tactical Directive. [139]

Almost immediately after Petit hung up, another secure phone rang. It was a major that Petit knew from Task Force–South, a Ranger-led Special Operations unit also based at Kandahar Air Field, whose unit carried out HVI targeting and relied heavily on remote platforms for ISR. [140] They had also been watching the Predator feed, and he told Petit this situation was ‘along the lines of their mission set.’ He offered to send an Attack Weapons Team – AH-64 Apache helicopters – to conduct an Aerial Vehicle Interdiction (AVI) in which the vehicles would be forced to halt, ideally without opening fire, so they could be searched and the occupants questioned (p. 725). This was in accordance with standard US military doctrine – which stipulates that ‘missions attacking targets not in close proximity to friendly forces … should be conducted using air interdiction (AI) procedures’(my emphasis) [141] – so that if the occupants proved to be hostile they could be engaged in full knowledge of their intent. This chimed with Cowan’s recommendation, and the Day Battle Captain agreed that an escalation of force was the right response in the circumstances (‘the best bet’: p. 1230). The Fires Officer was also cautious, but preferred a different course of action. In his view, the vehicles had changed ‘from tactical maneuvering to just travelling,’ as one of McHale’s team put it (p. 724), and he suggested that ‘we continue to follow with the Predator and watch to see where they go.’ This had been the GFC’s original intention too. ‘I thought we could get better intelligence by watching to see where they go and who they link up with,’ the Fires Officer told Petit, ‘rather than interdicting them.’ But Petit had evidently absorbed enough of Benton’s argument – and the requirements of the Tactical Directive – to make him reluctant to wait and see what developed. If they failed to act, the vehicles might end up ‘somewhere we couldn’t stop them at that point, like a compound’ (pp. 725-6). And so it was agreed to arrange an AVI.

The GFC was wholly unaware of these developments at SOTF-South and while all the discussions were taking place at Kandahar he had decided that his situation at Khod had become much more precarious. At 0744 the JTAC had told the Predator pilot that:

‘We just had [ICOM] traffic saying that all mujahedeen needs to start moving and come together. We currently have two groups that are talking to each other. I suspect that one of them is the group in the vehicle[s], and another [is the] group to the south of us.’ [142]

The GFC and the JTAC had no way to confirm their suspicions – presumably they had nothing from the NSA cell – but the GFC was also receiving radio reports from the outer checkpoints of his cordon to the north and the south that women and children were leaving their villages and ‘pushing to open ground’ – ‘which is normal when an attack is about to happen’ (p. 1356): ‘a direct reflection of an impending attack’ (p. 947) – and he could also hear a checkpoint manned by Afghan Security Guards much further to the south, outside his immediate area of operation, exchanging fire with insurgents who were using heavy machine guns abandoned by the Red Army when they withdrew from Afghanistan in 1988-9 (p. 947). [143]

By now the possibility that the three vehicles could be anything other than a threat had been abandoned by the GFC and the JTAC. At 0806 the JTAC radioed the Predator pilot: ‘Need to know as soon as they turn eastbound and come back to the green zone towards the direction of Khod.’ The pilot replied: ‘As soon as they break off to the east we will let you know’ (my emphases). No longer ‘if’ but ‘when’: the conditional had become the imminent because the JTAC had told the pilot that they had received ‘special intelligence that the [northern] group is trying to link up with another fighting force out of [Pay Kotal: a village to the south] that is moving up to Khod to engage our positions.’ [144] Calling those moving up from the south another fighting force sealed the fate of the occupants of the three vehicles travelling from the north. The possibility of encirclement had been preying on the GFC’s mind since the first reports of Taliban fighters converging on Khod from the south and the north at 0450 (above, p. 00), and at 0607 he had received another report that ‘insurgents state they have enough bodies to fight’ and ‘we won’t be able to leave the area’ (p. 937). The ICOM chatter at 0744 had made this seem all the more likely, and the ‘special intelligence’ delivered final confirmation. Putting all this together, the GFC was now convinced that the three vehicles were a Taliban convoy executing a flanking manoeuvre to complete the encirclement of his forces: ‘to close off the envelopment’ (pp. 946). The JTAC had concerns of his own. He was worried that bad weather forecast for that night and the next 48 hours would prevent the Chinooks returning to ferry them back to FB Tinsley. The contingency plan was to head south and link up with ‘a Commando mission’ that was supposed to come out the next day, but if they were encircled their escape route would be blocked and they would be trapped (p. 1357).

The GFC duly told SOTF-South that his forces were being ‘enveloped’ (p. 1358), but there was no requirement for him to inform them that in consequence he was about to clear the helicopters to engage the target. There had been circumstances in the past when ODAs taking fire from a compound had requested permission from the SOTF-South commander for an airstrike; sometimes he had agreed and at other times he had not (p. 1261). But the Tactical Directive specifically advised caution in striking residential compounds – hence the need to seek permission – whereas in this case the GFC deliberately chose to have the helicopters attack once the vehicles were in open country so the circumstances were different. [145] The GFC was prepared to bring the Predator in too, and at 0818 the JTAC issued the promissory note its crew had been hoping for. ‘At Ground Force Commander’s discretion,’ he radioed, ‘we may have [the OH-58s] come up, action those targets and let you use your Hellfire for clean-up shot.’

All of this was within the authority of the GFC. The Fires Officer at SOTF-South was primarily responsible for arranging air cover, both ISR and strike capability, but he explained they routinely established a decentralized ROZ (Restricted Operating Zone) so that once the aircraft were on station they were under the control of the JTAC acting for the GFC (p. 728). [146] This maximised the GFC’s freedom of manoeuvre, but it also recognised that the JTAC was in direct communication with the supporting aircraft so he and the GFC could have additional intelligence that was not immediately available to SOTF-South. An ROZ typically had a radius of 10 km or less – which would have placed the three vehicles outside its perimeter – but the Fires Officer was unconcerned because he believed the OH-58s were ‘not for the vehicles’ but for ‘what we thought was going to be a large TIC on the objective.’ He was emphatic about that, echoing the GFC’s original plan to allow the vehicles to close on Khod: ‘The [Scout] Weapons Team that was pushed forward to his location was not for the vehicles, it was for the possibility of a large TIC on the objective [Khod] based on the ICOM chatter that we had’ (pp. 734-5).[147]

But in the GFC’s eyes the situation was now very different, and even though he had no obligation to inform the Operations Center of his revised plan he was insistent that at ‘some time between 0820 and 0830’ he sent a SALT report to SOTF-South telling them he was going to clear the OH-58s to engage (p. 955) in response to an ‘imminent threat’ to coalition forces (p. 1495). [148] Astonishingly, McHale’s team were unable to verify his testimony because the pre-strike transcripts of SALT reports available to them ended at 0650 (p. 948). [149] No explanation for their absence was forthcoming, but the Day Battle Captain was equally insistent that once SOTF-South had agreed on an AVI, had the GFC contacted the Operations Center ‘and said that the OH-58s are on station and this is their tasking and purpose, I am going to give authorization to engage this convoy, we would have stopped that’ (p. 1258). It would almost certainly have had to be that way round, because it was so simple matter for SOTF-South to reach down to the GFC. The Fires Officer explained that the batteries that power the ODA’s satellite communications ‘don’t last long, and it was a “remain over day” mission so I am sure they had it turned off.’ ‘If we had pertinent information that we need to push,’ he continued, ‘we tell them to contact us on iridium [satellite phone]’ (p. 724). This required SOTF-South to send a mIRC message to the Predator crew, the pilot to relay the message to the JTAC via radio, and the GFC then to power up the iridium phone. [150]

NOTES

[101]The testimony offered by the major in command of the AC-130 claimed a reluctance to strike that is not evident from the communications transcript.

‘Without the [Redacted: ICOM?] I would not have considered [the vehicles] a threat because they were so far from the friendly forces… They were not an obvious direct threat but enough [of a] threat that I wanted to keep the sensors there… I don’t remember us telling them [the JTAC and GFC] specifically that they were hostile and a target. I do remember the JTAC would say a lot of things that would lead up to a fire mission and then he would stop. Of course my crew was ready to go but we need[ed] a fire mission’ (p. 1419).

But he also claimed that the JTAC ‘had the same understanding that we did’ and that, had he been given a fire mission, he would have been comfortable executing it (p. 1420). The Predator pilot thought there was more to it than that. ‘Talk of tactical maneuver [see above, p. 00] started with the [AC-130],’ he insisted, and ‘before they departed they were actually looking to engage these targets before running out of [fuel]’ (p. 909).

[102] The sensor operator offered anecdotal evidence to support the pilot’s inference. ‘There was a shot a couple of weeks ago, they were on those guys for hours and never saw them, like, sling a rifle, but pictures we got of them blown up on the ground had all sorts of [shit]’. Even this was barbed: evidently there had been no sign of any weapons, yet they were still ‘blown up on the ground’.

[103] Over the objections of the senior officers from Special Forces who read his draft report, McHale recommended the term be banned: ‘I believe eliminating the term MAM better serves the counterinsurgency strategy as the term has come to presume hostility’ (p. 69), and McChrystal concurred. The report retained its central objection: the term ‘implies that all adult males are combatants and leads to a lack of discernment in target identification’ (p. 49). Yet Nick Turse found that the mindset and even the term remained active: ‘America’s lethal profiling of Afghan men’, The Nation, 18 September 2013; see also Sarah Shoker, ‘Military-Age Males in US counterinsurgency and drone warfare’, unpublished PhD thesis, McMaster University, April 2018.

[104] Allinson, ‘Necropolitics’ p. 123.

[105] At McHale’s invitation all the previous mIRC messages were read into the record from the mIRC printout by the senior NCO in charge of Intelligence at CJSOTF-A’s Operations Center at Bagram during the night shift. It is impossible to know whether these were verbatim, but if they were then all of these messages referred to children without qualification. The NCO in question subsequently maintained that ‘it was all possible before the engagement’: but none of his readings included that qualifier.

[106] He was not alone. At 0546 the MC read from mIRC that SOTF-South ‘called the little small guys midgets.’

[107] This was presumably an evidentiary precaution; the metadata would have included co-ordinates and other information not visible on the image itself. No action was recorded until 0616, when the occupants left their vehicles to pray, and the sensor operator announced: ‘Stand by on that zoom out and drop metadata. I just wanted to scan everybody, I’ll get them a picture. I’m going to freeze it here for about 10 seconds then I’m going back.’ But nothing seems to have been made of any of this by McHale’s team, unless it is buried in the redactions.

[108] The unsupported claim cut both ways. The commanding officer of the 15th Reconnaissance Squadron e-mailed McHale to suggest that the presence of ‘human shields’ would ‘make everyone (including the JTAC) be more cautious about shooting’ (p. 897), and the Predator crew subsequently wondered how that would affect the Rules of Engagement (below, p. 00). But the use of the term was freighted with the implication that the occupants of the vehicles were mostly Taliban.

[109] In the Kunduz incident (above, p. 00), the hijacked tankers had first been located by a B-1 bomber which had to withdraw in the early hours of the morning because it was running low on fuel; in order to ensure continued air support the ISAF commander relied on what Wilke, ‘Seeing’, p. 1035 calls the ‘enabling fiction’ of a ‘TIC’ even though the tankers were 8-10 km from his own position and he had no forces in the immediate area of the target. Noah Shachtman described ‘TIC’ as ‘the most abused phrase in the Afghanistan campaign. What started as a cry for help has now come to mean almost anything…’: ‘The phrase that’s screwing up the Afghan air war’, Wired, 12 September 2009. What is being described here, however, is a different enabling device; McHale described an AirTIC as an ‘improper declaration’ that put other troops at risk by ‘allocating air assets to a situation which does not require air support’ (p. 48). The appropriate term for a potential engagement was ‘priority immediate’, and the Director of the CJSOTF–A Operations Center at Bagram explained that a TIC number was assigned to those calls (too), which served to ‘alert us all that a unit may be getting involved in a TIC soon’ (p. 807). The practice was not confined to Special Forces; the ‘Afghan War Diaries’ include multiple instances of AirTICS being declared by regular forces: https://wardiaries.wikileaks.org.

[110] Hence ‘Scout’ Weapons Team flying OHs (‘Observation Helicopters’); an Attack Weapons Team would typically consist of two AH-64 Apache helicopters (where AH designates ‘Attack Helicopters’).

[111] A battle captain assists the battalion’s executive officer in orchestrating (supervising, synchronizing and coordinating) the running of a Tactical Operations Center; s/he is responsible for overseeing the flow of information – including the SALT reports sent up from units in the field – tracking ongoing operations, and arranging appropriate support. A battle captain follows standard operating procedures, including initiating ‘battle drills’ (a rapid sequence of pre-set actions) in specified circumstances. For a detailed discussion see pp. 1100-1. The battle captain is a central actor in the bureaucratic management of later modern war, but the situations with which s/he is confronted often require a more fluid responses than these programmatic systems imply: see Elizabeth Owen Bratt, Eric Domeshek, and Paula J. Durlach, ‘The first report is always wrong, and other ill-defined aspects of the Army Battle Captain domain’, Intelligent Tutoring Technologies for Ill-Defined Problems and Ill-Defined Domains (2010).

[112] The OPCENT director similarly described his skills as ‘rudimentary at best’ (p. 999).

[113] The GFC was only too well aware of the lack of support and what he characterized as a ‘huge communication breakdown’. ‘I never had these issues before,’ he explained: ‘If for some reason I was in this situation last rotation … [the battle captain] was smart enough to … say call me on the phone and we would walk through certain things. “This is what I am tracking, why don’t you concentrate on this, and if this develops I will push it to you’” (p. 983). He felt uneasy, he confessed, because ‘we are operating by ourselves, and not with direct support like we are supposed to have’ (p. 984). Part of the problem – perhaps – was that they were strangers to SOTF-South (see note 63) and, as the GFC admitted himself, ‘we never integrated our systems with them’ (p. 985).

[114] This was a serious failure, but McHale’s team faulted a battle rhythm in which all three field-grade officers were asleep at the same time. ‘I would have had an easier time if you said you had a field grade up at 0600 because we know the mission is kicking off at 0605,’ one of the investigating officers said. ‘But you don’t…’ (p. 1015).

[115] This was a central finding of McHale’s investigation, which concluded that the GFC was ‘overly tasked’ (pp. 34-5), as a direct result of the lack of input or support from the Special Forces command posts at Kandahar and Bagram Air Fields.

[116] See Craig Jones, The war lawyers(Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

[117] He was responding to a question about the presence of an ‘operational law attorney’, a JAG incorporated into the kill-chain and conversant with air targeting; there was a JAG present during McHale’s initial telephone interview with the Predator crew, but she was introduced as ‘the Creech AFB JAG’ who was representing ‘the Air Force interests’ and her expertise presumably lay outside ‘operational law’ (p. 902). The Safety Observer explained his own role as ‘basically a safety mechanism to ensure they are performing safely and to provide a sanity check [sic] before employing the missile’ (p. 1448).

[118] The 9-liner in this case is a standard Air Force targeting brief that specifies (1) the ‘initial point ‘, (2) heading (to target), (3) distance, (4) elevation, (5) target description, (6) target location, (7) target mark (laser designator &c), (8) friendly force location and (9) aircraft exit route.

[119] The commanding officer of the 15th Reconnaissance Squadron explained that ‘If it is an HVI [High-Value Individual] where there is no imminent hostile act or hostile intent, not only do we need the JTAC’s clearance on that, the GFC will go through the CAOC and get what is called the joint targeting method, so it is a kind of dual clearance’ (p. 887).

[120] Hoog, ‘Air power over Afghanistan’, p. 249. He explained that there was a distinction between a TIC, which he too described as ‘a 911 call for kinetic support’ and a ‘Priority’, which was ‘a 411 call’ for ISR (i.e. information and, by extension, overwatch).

[121] Jack Mulcaire, ‘The pickup truck era of warfare’, War on the Rocks, 11 February 2014 at https://warontherocks.com/2014/02/the-pickup-truck-era-of-warfare. The Toyota Hilux is a classic version of a technical truck – and the lead vehicle was identified as a Hilux.

[122] Only two witnesses offered any informed gloss on the hostile interpretation of the prayer. The Day Battle Captain suggested that it ‘possibly’ indicated ‘these are mujahedeentaking their last prayer prior to engaging forces’ (p. 1254), and the primary screener agreed: ‘To us that is very suspicious because we are taught that they do this before an attack’ (p. 1389).

[124] Alan Norris, ‘Flying with the Wolfpack’, Heliops International 65 (2010) 40-49. Each helicopter was armed with two Hellfire missiles and four folding-fin aerial rockets.

[125] The transcript of the Kiowas’ radio traffic (pp. 336-341) contains no times; wherever possible I have interpolated these transmissions with those between the JTAC and the Predator pilot, which was conducted on a different frequency.

The reference to ‘heavy weapons’ in this message is puzzling; the Predator crew had not succeeded in identifying any, and the only SALT report mentioning ‘heavy weapons’ was at 0330 and referred to Taliban forces moving up from the south before the vehicles moving down from the north had even been detected (p. 1889). The source of the transmission is unclear; most of the messages to the JTAC were from the lieutenant, but the pilot flying lead said that he ‘called to tell him [the JTAC] that we were on our way and that it would be about 30 minutes until we were in the area. He told me that it was roughly 30-50 MAMs to his north that we would be looking to engage’ (p. 514). But this exchange does not appear in the transcript in this form, though it obviously overlaps with the message I have cited here and attributed to the lieutenant in command of SWT1. The intended recipient is also unclear; the JTAC would have known (in fact, supplied) all this information, so it is possible that this was a confirmatory message either to TF Wolfpack’s Operations Center at Tarin Kowt or to the JTAC at FB Ripley who had been tasked with communicating with the helicopters until they were in range of the JTAC at Khod.

[126] The only qualification came from one of the crew in the trail helicopter: ‘Initially I thought we had a kinetic TIC, but it turned out not to be…. [We] got information it was more of elements maneuvering on [the ODA’s] position’ (p. 1438).

[127] McHale’s report included a map of SIGACTS (‘significant activities’) in Uruzgan which was redacted (p. 376), but raw data for Shahidi Hassas in the 12 months preceding the strike reported 73 SIGACTS, 25 of them involving direct fire, 8 indirect fire, and 7 small arms fire. I have taken these figures from the Afghanistan SIGACTS files kindly made available by Vincent Bauer at https://stanford.edu/~vbauer/data.html

[128] Many at SOTF-South were also taken aback: ‘We did not push fast movers to them,’ the Night Ops NCO at Kandahar told McHale: ‘The fast movers just came over the area without our knowledge’ (p. 1505). The Night Battle Captain asked how this could have happened and was told ‘when an AirTIC is opened everyone wants to get on it. When they hear AirTIC they think worst case scenario’ (p. 1545). But none of the available communications authorizing air cover referred to an AirTIC – this was, as far as the responding aircrews were concerned, a TIC – and at 0702 the MC referred to it as ‘an actual TIC.’ The Fires Officer at SOTF-South evidently realized that the F-15s had been sent instead of the A-10s that had been half-promised and told them to hold well to the south of the vehicles’ position and to contact the JTAC at FB Tinsley who would control them ‘until the actual TIC happens near the village of Khod’ at which point he would pass them off to the JTAC there (p. 721). After the GFC’s angry phone call they were sent off station.

[129] Col. Peter E. Gersten, quoted in Donna Miles, ‘Unmanned Aircraft crews strive to support warfighters. American Forces Press Service, 13 November 2009.

[130] One of the helicopter pilots heard the F-15s being ordered off, but in conjunction with the Predator pilot reporting his aircraft was descending to 13,000 feet (above) thought the F-15s had been cleared to engage ‘but due to low ceilings and conflicting altitudes with the Predator UAV they were pulled off target’ (p. 420). He was wrong, but the belief that the F-15s had been cleared to engage conceivably reinforced his own sense of the legitimacy of the target.

[131] Afghanistan Civilian Casualty Prevention: observations, insights and lessons (Fort Leavenworth KS: US Army Combined Arms Center/Center for Army Lessons Learned [CALL], June 2012) p. 30.