It’s strange how things sometimes come together…. News of the online publication of Stuart Elden‘s paper, ‘Secure the volume: vertical geopolitics and the depth of power‘, coincides with a short post from Jasper Humphreys at the Marjan Centre, ‘Shape shifting in Flanders‘, which describes the war on the Western Front as the first 3-D war. What Jasper has in mind is the combination of aerial reconnaissance (and artillery spotting) with the elaborate tunnelling under enemy lines to detonate huge explosions. But if we extend the terrain beyond the Western Front then the claim becomes a more general and I think an even more powerful one, with the bombing of civilian targets far beyond the front lines by airships and aircraft and the unrestricted use of that ‘ungentlemanly weapon’, the submarine. (Stuart cites Paul Virilio‘s Bunker Archaeology, which identifies the emergence of ‘volumetric’, deep three-dimensional warfare with the Second World War, but the genealogy is clearly older than that).

It’s the underground war – the tunnellers’ war – that captures Jasper’s attention. He focuses on the mining of Messines Ridge in June 1917, which (as he notes) appears in Sebastian Faulkes‘s Birdsong, but the tactic was a general one that not only scarred the landscape but also left an indelible impression on everyone who witnessed it, even by proxy: the detonation of the mine beneath Hawthorn Ridge in July 1916 was filmed by Geoffrey Malins for The Battle of the Somme (below).

It’s the underground war – the tunnellers’ war – that captures Jasper’s attention. He focuses on the mining of Messines Ridge in June 1917, which (as he notes) appears in Sebastian Faulkes‘s Birdsong, but the tactic was a general one that not only scarred the landscape but also left an indelible impression on everyone who witnessed it, even by proxy: the detonation of the mine beneath Hawthorn Ridge in July 1916 was filmed by Geoffrey Malins for The Battle of the Somme (below).

Mining had started with the onset of trench warfare, and was dominated by the Germans during 1914 and 1915: ‘Although Germany had rejected military mining by 1914,’ Simon Jones notes, ‘it was nevertheless able quickly to revive its capability through the availability of fortress troops which could be attached ot its field army. There seemed no alternative but to mine on the Western Front as a means of breaking the strong field defences.’ For the British and their allies mining evolved, if that’s the right verb, into three main phases: the Somme in 1916, Arras in April 1917 and – though its efficacy was by then undermined by the German strategy of defence-in-depth – Messines in June 1917.

Hill 60 on the Messines Ridge had been mined in 1915, but the re-mining in June 1917 – as part of ‘the largest mining attack in the history of warfare’ (Jones) – was hugely spectacular:

‘The artillery preparations which for days had been intense had died down and the night was comparatively quiet… Suddenly, all hell broke loose. It was indescribable. In the pale light it appeared as if the whole enemy line had begun to dance, then, one after another, huge tongues of flame shot hundreds of feet into the air, followed by dense columns of smoke which flattened out at the top like gigantic mushrooms. From some craters were discharged tremendous showers of sparks, rivalling everything ever conceived in the way of fireworks.’

I’ve taken this from an essay by Roy MacLeod, ‘Phantom soldiers’, which provides an excellent discussion of Australian tunnellers in the underground war and emphasizes that theirs was a profoundly scientific campaign that involved knowledge of geology, engineering and – crucial for counter-mining – acoustics. If it was science, it was doubly hellish science, both for the conditions endured by the tunnellers and for the consequences on the surface. In Underground warfare Simon Jones includes this report from a British artillery officer:

‘At exactly 3.10 a.m. Armageddon began. The timing of all the batteries in the area was so wonderful and to a second every gun roared in one awful salvo. At the same moment the two greatest mines in history were blown up… First there was a double shock that shook the earth here 15,000 yards away like a gigantic earthquake. I was nearly flung off my feet. Then an immense wall of fire that seemed to go half-way up to heaven. The whole country was lit with a red light like a photographic dark-room… The noise surpasses even the Somme; it is terrific, magnificent, overwhelming. It makes one almost drunk with exhilaration…’

Barely two months later photographer Frank Hurley peered down at the huge crater in horror:

‘After, we climbed to the crest of hill 60, where we had an awesome view over the battlefield to the German lines. What an awful scene of desolation! Everything has been swept away: only stumps of trees stick up here & there & the whole field has the appearance of having been recently ploughed. Hill 60 long delayed our infantry advance, owing to its commanding position & the almost impregnable concrete emplacements & shelters constructed by the Bosch. We eventually won it by tunnelling underground, & then exploding three enormous mines, which practically blew the whole hill away & killed all the enemy on it. It’s the most awful & appalling sight I have ever seen. The exaggerated machinations of hell are here typified. Everywhere the ground is littered with bits of guns, bayonets, shells & men. Way down in one of these mine craters was an awful sight. There lay three hideous, almost skeleton decomposed fragments of corpses of German gunners. Oh the frightfulness of it all. To think that these fragments were once sweethearts, may be, husbands or loved sons, & this was the end. Almost back again to their native element but terrible. Until my dying day I shall never forget this haunting glimpse down into the mine crater on hill 60, – & this is but one tragedy of similar thousands…’

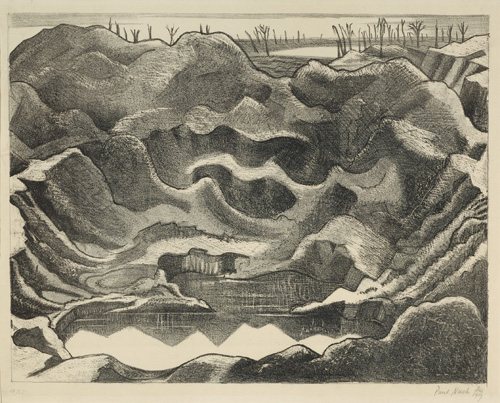

The nightmare scene was also the subject of Paul Nash‘s famous sketch, completed in November:

The BBC has a gallery of images of the underground war, which includes two maps of trenches and tunnels, here, and there’s a fascinating report of contemporary archaeological excavations of the same site here. There are also helpful discussions and diagrams here. But the most comprehensive discussion is undoubtedly Simon Jones‘s Underground warfare 1914-1918 (2010), which includes compelling first-hand accounts from the tunnellers and countless others.

The BBC has a gallery of images of the underground war, which includes two maps of trenches and tunnels, here, and there’s a fascinating report of contemporary archaeological excavations of the same site here. There are also helpful discussions and diagrams here. But the most comprehensive discussion is undoubtedly Simon Jones‘s Underground warfare 1914-1918 (2010), which includes compelling first-hand accounts from the tunnellers and countless others.

In the course of his own discussion, Jasper makes two other observations that also intersect with some of my current preoccupations. The first is about the familiarization of the landscape of war by the first artists despatched to the front, though I’m less interested in the pastoral aesthetic than in subsequent, thoroughly modernist attempts to capture the ‘anti-landscape’ of the war.

The second is about the earthy, material medium through which the war was fought:

‘No war in history has combined such a vast theatre of operations fought in such proximity to the forces of Nature: firstly the elements of wind, rain, storms and snow created the all-pervasive mud and water – sometimes referred to metaphorically as ‘slime’ – along with the horses, mules, dogs and canaries, as well as rats and mice, all sharing the hell of the trenches with humans. Secondly, the geography and topography dominated the fighting: every small hill, river or indentation that would provide even a tiny advantage was a battle-ground.’

I’ve posted about these ‘slimescapes‘ before, and they loom large in my presentation on ‘Gabriel’s map’, but earlier this year I agreed to give a new public presentation this May (at the Vancouver Aquarium – where else?) on ‘The natures of war’ in which I develop the argument in more – er – depth. I won’t be confining myself to the First World War, though I expect to have much to say about trench and tunnel warfare, and in particular I want to think through ‘nature’ less as the arena over which conflicts are fought (‘conflict commodities’, ‘resource wars’, and the rest) and more about nature as the medium through which conflict is conducted. I’m assuming we can all agree that ‘nature’ is just as complex as Raymond Williams said it is, and that here it’s just a shorthand that will need very careful unpacking – or perhaps excavating. More soon…

Pingback: The Anthropocene Project « geographical imaginations

Pingback: From Above « rhulgeopolitics

Reblogged this on rhulgeopolitics and commented:

Very exciting developments at geographical imaginations on 3-D war