I’ve had several inquiries about my recent posts on bombing in the First World War (here and here), all of which want to know why I’ve gone back so far. Isn’t it all so remote? they ask. I’d hoped I’d started to answer that in my previous posts, but Tami Davis Biddle – the author of Rhetoric and reality in air warfare (Princeton University Press, 2004) – provides a succinct answer in her ‘Learning in real time: the development and implementation of air power in the First World War’ (in Sebstian Cox and Peter Gray, eds., Air power history: turning points from Kitty Hawk to Kosovo):

I’ve had several inquiries about my recent posts on bombing in the First World War (here and here), all of which want to know why I’ve gone back so far. Isn’t it all so remote? they ask. I’d hoped I’d started to answer that in my previous posts, but Tami Davis Biddle – the author of Rhetoric and reality in air warfare (Princeton University Press, 2004) – provides a succinct answer in her ‘Learning in real time: the development and implementation of air power in the First World War’ (in Sebstian Cox and Peter Gray, eds., Air power history: turning points from Kitty Hawk to Kosovo):

‘Virtually every important manifestation of twentieth-century air power was envisioned and worked out in at least rudimentary form between 1914 and 1918.’

She has in mind many of the practices I’ve described in my previous posts – and there’s more to come – but I’ve just stumbled upon one that neither of us anticipated. And, yes, it is ‘remote’…

Gary Warne has a remarkable post, ‘The Predator’s ancestors: UAVs in the Great War’, in which he describes Captain Archibald Low’s Aerial Target project. The codename was a deliberate distraction, Warne explains, because the plan was to develop a pilotless aircraft as a flying bomb, guided by wireless from an accompanying manned aircraft to attack Zeppelins and ground targets. The fullest discussion of Low’s work that I’ve been able to find is by Paul Hare here; some of the back-story is provided by Hugh Driver in The birth of military aviation 1903-1914 (Boydell and Brewer, 1997) and there’s a wider historical discussion in Chapter 2 of Denis Larm‘s thesis here.

When the war started ‘Professor’ Low, as he styled himself, was already at work on artillery range-finding and, newly commissioned, was soon at the forefront of the Royal Flying Corps’s Experimental Works (below; Low is in the centre of the front row), supervising a team of 30, including jewellers, carpenters and engineers first at a Chiswick garage and later at Brooklands.

The noise of the aircraft engine interfered with the wireless transmissions, and the first demonstration flight of the Aerial Target was a disaster. According to Steven Shaker and Alan Wise in War without Men: robots on the future battlefield (Pergamon-Brassey, 1988), ‘during a test flight for a gathering of important Allied dignitaries, the AT went astray and dove upon the guests, who scattered in every direction.’ All together six prototypes were constructed in 1917, but none of them saw combat.

The noise of the aircraft engine interfered with the wireless transmissions, and the first demonstration flight of the Aerial Target was a disaster. According to Steven Shaker and Alan Wise in War without Men: robots on the future battlefield (Pergamon-Brassey, 1988), ‘during a test flight for a gathering of important Allied dignitaries, the AT went astray and dove upon the guests, who scattered in every direction.’ All together six prototypes were constructed in 1917, but none of them saw combat.

That last verb is spot on, however, because in March 1914 Low had successfully demonstrated what he called TeleVista, an early version of television, and the Times reported that ‘if all goes well with this invention, we shall soon be able, it seems, to see people at a distance’ – a capability that, over 50 years later, would be integral to the USAF’s experiments with reconnaissance drones over North Vietnam (see ‘Lines of descent’, DOWNLOADS tab) and, of course, to today’s Predators and Reapers. As the Times continued, it was an open question ‘whether Dr Low will be regarded as a benefactor, or the opposite.’

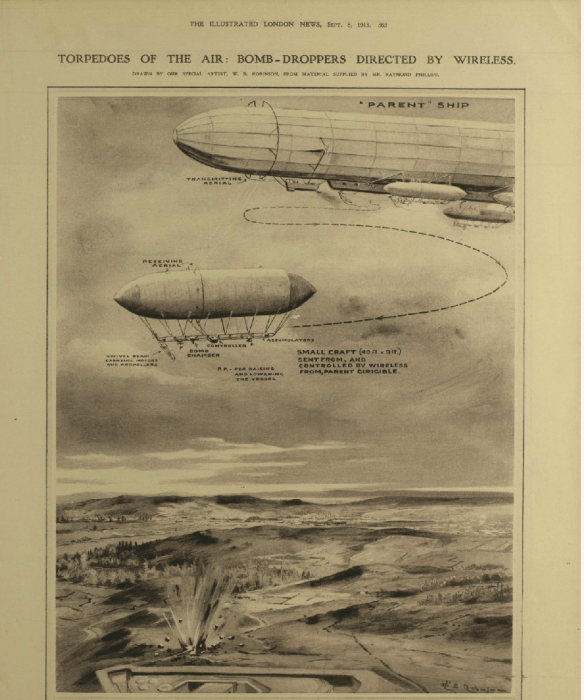

Low never linked his two projects, but in fact the prospect of seeing a distant target had been mooted before the war. In 1910 Raymond Phillips used a twenty-foot model Zeppelin to demonstrate his wireless-controlled ‘aerial torpedo’ before an entranced crowd at the London Hippodrome. According to the New York Times (22 May 1910):

Low never linked his two projects, but in fact the prospect of seeing a distant target had been mooted before the war. In 1910 Raymond Phillips used a twenty-foot model Zeppelin to demonstrate his wireless-controlled ‘aerial torpedo’ before an entranced crowd at the London Hippodrome. According to the New York Times (22 May 1910):

‘He claims to be able, sitting at a transmitter in London, to send a dirigible balloon through the air at any height and almost any distance. He can load his balloon with dynamite bombs, he claims, and without leaving his office can send it over a city and wipe the city out.’

He told his audience:

‘I don’t want to brag, but I feel sure that if England purchases my aerial torpedo she will make short work of the enemy’s fleets and cities in any future war. Why, I can sit in an armchair in London and drop bombs in Manchester or Paris or Berlin.’

Given the first city on his list it’s scarcely surprising that there should have been questions about navigation. Asked how he would know that his airship was over ‘the town you purpose to destroy’, Phillips replied that he might work with a large-scale map or a ‘telephotographic lens’. ‘I think it will do away altogether with existing methods of warfare,’ he predicted. Much more here (scroll down).

But one of his rivals in the audience had spotted a weakness in the system. ‘I believe that it would be possible for another operator to interfere with Mr Raymond Phillips’ control,’ speculated Harry Grindell Matthews, using what one newspaper called ‘hostile electric currents’, and he predicted that he could, ‘by manipulating an instrument of my own, compel it [the airship] to turn round and return to the place from which it was sent.’ The two men agreed to a duel between their devices, but I’ve been unable to find any record of the outcome – though the spectre that Matthews raised remains a concern for today’s remotely piloted operations. Incidentally, Matthews would later claim to have invented a ‘death ray’…. More on him here and here.

But one of his rivals in the audience had spotted a weakness in the system. ‘I believe that it would be possible for another operator to interfere with Mr Raymond Phillips’ control,’ speculated Harry Grindell Matthews, using what one newspaper called ‘hostile electric currents’, and he predicted that he could, ‘by manipulating an instrument of my own, compel it [the airship] to turn round and return to the place from which it was sent.’ The two men agreed to a duel between their devices, but I’ve been unable to find any record of the outcome – though the spectre that Matthews raised remains a concern for today’s remotely piloted operations. Incidentally, Matthews would later claim to have invented a ‘death ray’…. More on him here and here.

The theatricalization of these early projects, with Phillips’s airship nosing its way around the Hippodrome – which was originally designed as a circus and had only been remodelled the previous year – and releasing its load of paper birds forty feet above the stalls, is all of a piece with the ‘bombing competitions‘ and the air displays of the pre-war years.

Here is Flight magazine on 7 May 1910:

‘There is no accounting for popular taste in the matter of public entertainment, but we must confess one could scarcely expect to witness the spectacle of a fairly big model dirigible sailing about the auditorium of the London Hippodrome, where at the moment it constitutes one of the star turns….

‘As an indication of a phase of aeronautics that is quite likely, indeed, we might as well say quite certain, to figure in the future, this display at the Hippodrome is a thoroughly interesting and instructive turn, and brings before many hundreds of people a visual demonstration of a scientific subject that in the ordinary course of events they would only be likely to read about at the best.’

Yet another instance of the theatre of war.

Phillips persisted with his dream, and in September 1913 the Illustrated London News devoted a whole page to ‘torpedoes of the air’ – what it called ‘bomb-droppers directed by wireless’ – and Robinson’s drawing was based on ‘materials provided by Mr Raymond Phillips.’