I’ve been working on my essay on ‘Woundscapes of the Western Front, 1914-1918’. What follows is the section dealing with the act of being wounded, drawn from a series of diaries, letters and memoirs; it’s followed by a section fleshing out the concept of a woundscape which I’ll post in due course [for a preliminary sketch, see here].

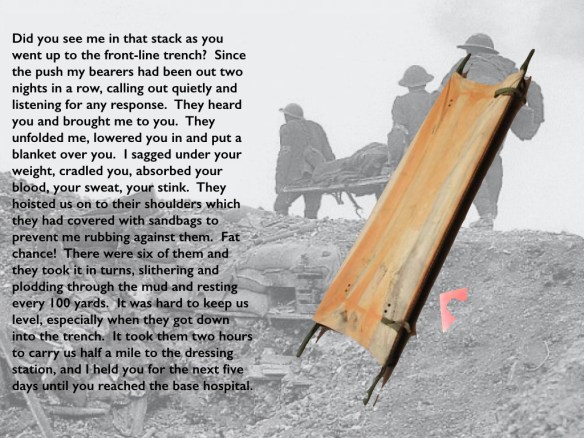

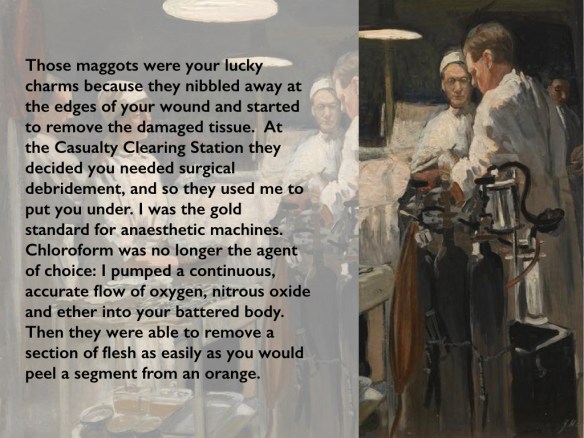

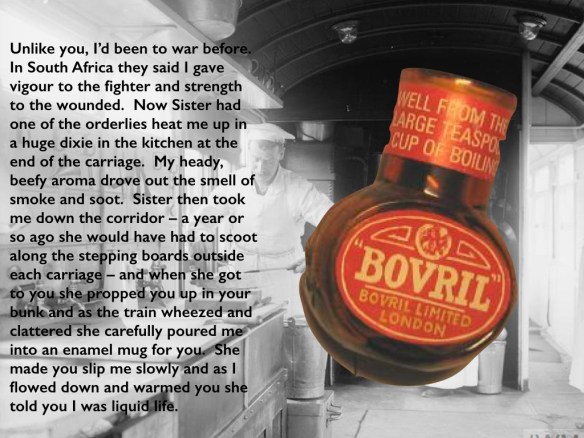

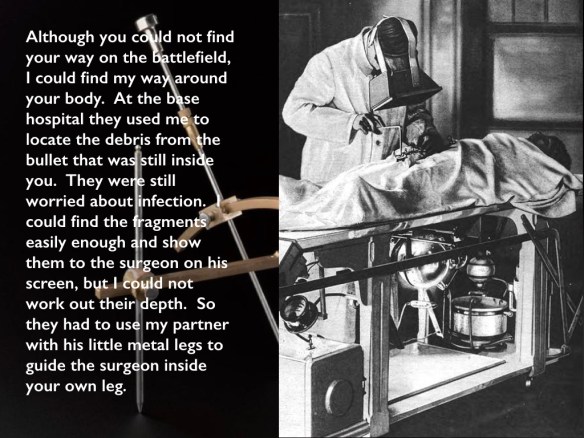

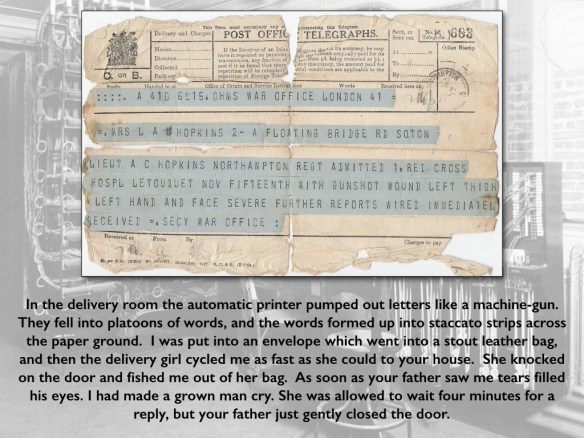

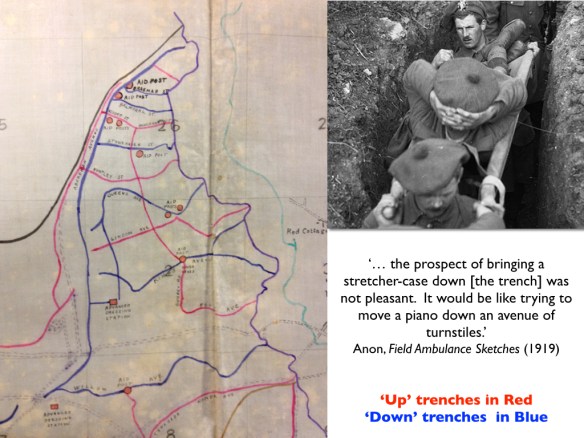

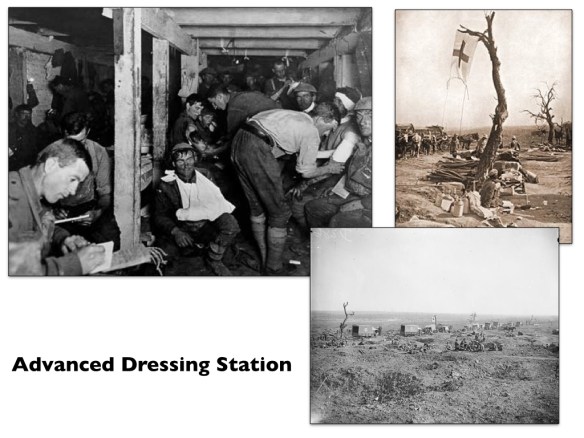

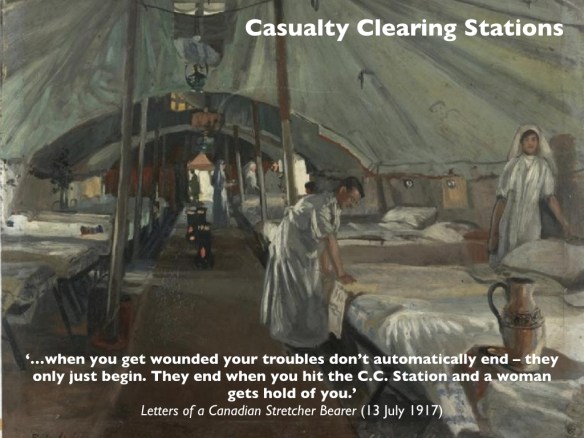

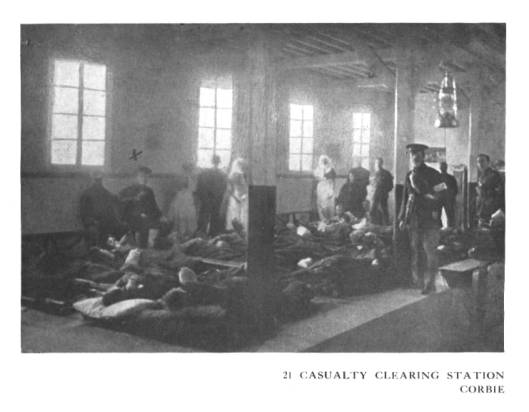

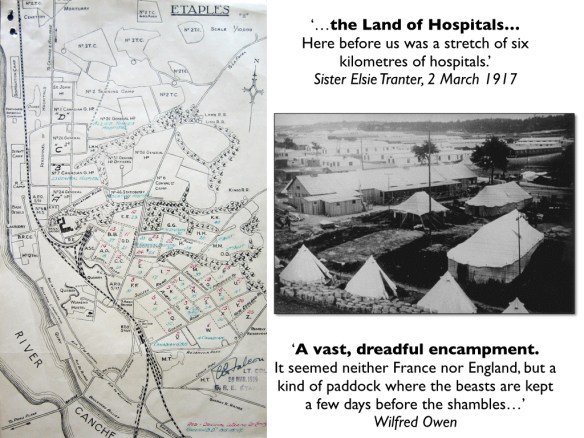

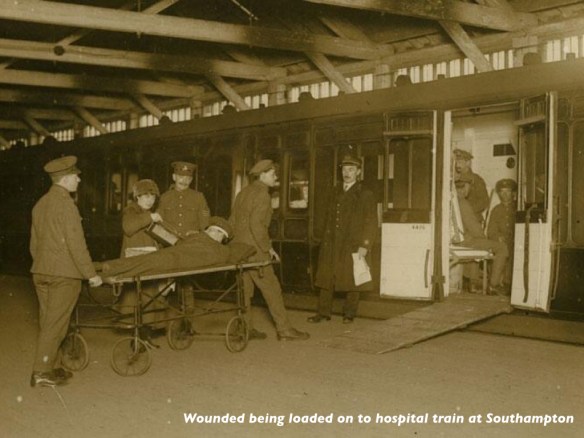

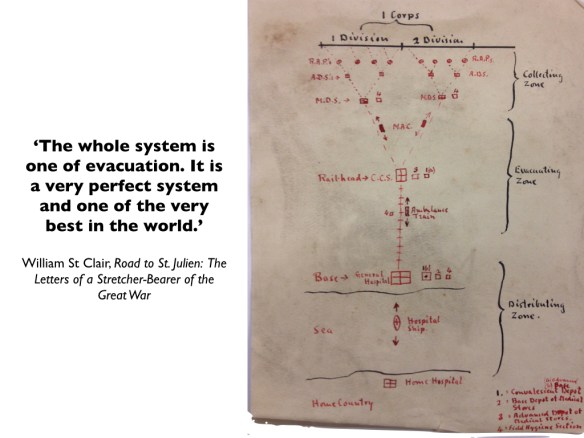

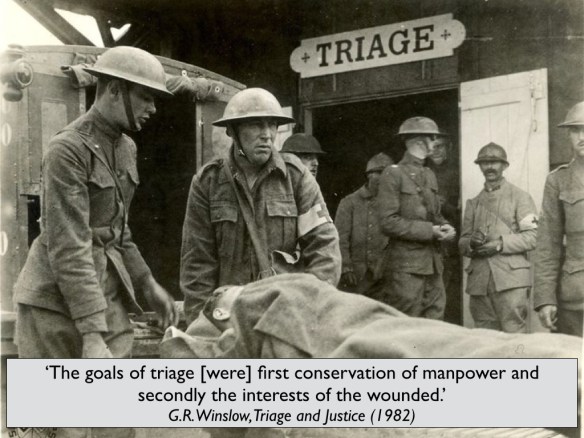

Subsequent sections reconstruct the precarious journey of casualties from the point of injury through the aid posts, dressing stations and casualty clearing stations to the base hospitals on the French coast and beyond (for a quick sketch, see here, and for an experimental version inspired by Harry Parker‘s Anatomy of a soldier, see here).

This is very much a working version, so please read it as such – and as always I’d welcome any comments or suggestions. I’ve added some links and images (most of them from my presentations), though those included in the final version are likely to be different.

I should add that this is one part of a much larger project that also considers medical care and casualty evacuation in other war zones: the Western Desert in the Second World War, Vietnam, and Afghanistan and Syria today.

***

John Keegan once remarked that in military histories the wounded seem to ‘dematerialize as soon as they are struck down’. [1] This matters for more than historical reasons, however, because the wounded serve as a testament to what Elaine Scarry insists is ‘the main purpose and outcome of war’, which is to say injuring. This ugly fact, she argues, can be ‘made to disappear from view along many separate paths.’ [2] In order to bring it back, I attempt to have the wounded reappear on – and through – the paths they followed after they were injured. Most of what I have to say is confined to the British Army and its colonial and imperial counterparts from Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand and South Africa on the Western Front. [3] The details differ in other militaries and other theatres, but the elemental geography of casualty evacuation was a general one. My focus is confined to the effects of physical injury and I do not directly address what was eventually diagnosed as ‘shell shock’, but it will soon become clear that the trauma of being wounded was far from a purely physical affair and that it was suffused with emotional reactions that played a vital role in rescue and recovery. [4]

Trauma typically ruptures ordinary language – another of Scarry’s astute insights – and it is scarcely surprising that many witnesses to the broken bodies trailing across the battlefields should have turned to metaphor to convey the enormity of the toll.[5] On 1 July 1916, the first day of the battle of the Somme [above], a British officer found his trench ‘blocked with wounded men who were trying to make their way back to the dressing station’, and as Capt Radclyffe Dugmore surveyed the scene he was struck by the mechanical nature of both military violence and military medicine.

‘Here was this line of men, who little more than an hour ago were normal men in the finest of health and strength, and now maimed, and with every degree of injury, they painfully made their way back to the human repair department. The well men were rapidly moving eastward in countless numbers, going forward to the assistance of their comrades, while the injured so laboriously dragged their way back, two human streams, the sound and the unsound. Before us, all energies were devoted to destruction; behind us, all human power and skill tried to repair the damage.’ [6]

.The language of ‘wrecks’ was commonplace. To Sister Kate Luard ‘the wards [were] like battlefields, with battered wrecks in every bed.’ The task of casualty evacuation, explained one medical orderly, was ‘to move these helpless pieces of wreckage, as rapidly and comfortably as may be, to the place where they will in due course be repaired.’ [7] The language of ‘repair’ was a common one too, and I will return to its significance shortly.

Three weeks after Dugmore’s observation, and not far from his position, a wounded Australian soldier making his way from aid post to dressing station described the same awful scene but in a different, animate register:

‘Ahead of us and behind us as far as the eye could see, a long column of walking wounded slowly made their way through the valley and across the ridges. From a distance the khaki column resembled a huge brown snake crawling across the country.’ [8]

Hartnett’s pained allusion was evidently not to a serpent entwined around a staff, the classical symbol for medicine; the intended effect was altogether more venomous. [9] Still more sinister was the common imagery of the shambles and the slaughterhouse. Wilfred Owen described the infantry training camp on the French coast at Étaples as ‘neither France nor England, but a kind of paddock where the beasts are kept a few days before the shambles.’ In the sixteenth century a shambles was an open-air slaughterhouse, and the term was readily extended to the modern battlefield. Watching the stretcher-bearers file past after the Battle of Festubert with their burden of bloodied bodies one Guards officer recoiled in horror: ‘fine upstanding fellows only a few hours before’, they had become ‘nauseatingly repulsive’, ‘hideously injured carcases.’ Doctors sometimes had the same reaction and resorted to the same imagery. ‘Although but a middleman,’ confessed Capt Lawrence Gameson at a dressing station on the Somme, ‘one gets sick of blood’s smell and of the endless everlasting procession of red raw human meat passing through our hands.’If the injured survived they were consigned to a Casualty Clearing Station, what one senior medical officer – one of many, as it turns out – called his ‘Butcher’s Shop’, wherein Philip Gibb was nauseated by the ‘great carving of human flesh’. One chaplain remembered a surgeon who had been working 24 hours without a break: ‘In the middle of it all he turned away from one table and looked up as another one was being carried in, and he shook his head. He was covered in blood – we all were – and he said, “This isn’t a hospital, it’s a butchery.”’ [10]

Those two imaginaries, the mechanical and the animate, collided most explosively and intimately in the act of being wounded. Those who wrote about it often expressed their surprise, even disbelief that it had happened to them – pain came later – or registered the immediate sensation of a tremendous blow. On the first day of the Somme it never occurred to Lt Edward Liveing that he had been wounded:

‘Suddenly I cursed. I had been scalded in the left hip. A shell, I thought, had blown up in a water-logged crump-hole and sprayed me with boiling water. Letting go of my rifle, I dropped forward full length on the ground. My hip began to smart unpleasantly, and I felt a curious warmth stealing down my left leg. I thought it was the boiling water that had scalded me. Certainly my breeches looked as if they were saturated with water. I did not know that they were saturated with blood.’ [11]

But when Sgt R.H. Tawney was hit later the same day he had no doubt he had been hurt:

‘I felt … that I had been hit by a tremendous iron hammer, swung by a giant of inconceivable strength, and then twisted with a sickening sort of wrench so that my head and back banged on the ground, and my feet struggled as though they didn’t belong to me. For a second or two my breath wouldn’t come. I thought – if that’s the right word – “This is death”, and hoped it wouldn’t take long. By-and-by, as nothing happened, it seemed I couldn’t be dying. When I felt the ground beside me, my fingers closed on the nose-cap of a shell. It was still hot, and I thought absurdly, in a muddled way, “this is what has got me”. I tried to turn on my side, but the pain, when I moved, was like a knife, and stopped me dead. There was nothing to do but lie on my back.’ [12]

Three weeks later, still on the Somme, Lt Robert Graves had a similar sensation when he was seriously wounded. ‘An eight-inch shell burst three paces behind me,’ he recalled.

‘I heard the explosion, and felt as though I had been punched rather hard between the shoulder blades, but without any pain. I took the punch merely for the shock of the explosion; but blood trickled into my eye and, turning faint, I called to Moodie [his company commander]: “I’ve been hit.” Then I fell…’ [13]

His friend Lt Siegfried Sassoon’s reaction to being wounded during the Battle of Arras the following year)was much the same. He too knew at once that he had been hurt, even if he was not sure how. ‘No sooner had I popped my silly head out of the sap,’ he wrote much later, ‘than I felt a stupendous blow in the back between my shoulders. My first notion was that a bomb [grenade] had hit me from behind, but what had really happened was that I had been sniped from in front…To my surprise I discovered that I wasn’t dead.’ [14]

As these accounts indicate, for many wounded soldiers the proximity of death was palpable: space sensibly contracted to their wound, their body and its immediate surroundings. ‘A man badly knocked out feels as though the world had spun him off into a desert of unpeopled space,’ Tawney admitted: a feeling heightened by the standing order forbidding troops from stopping to aid the wounded during an advance. ‘Combined with pain and helplessness,’ he continued, ‘the sense of abandonment goes near to break his heart.’ [15] When Pte David Jones was shot in the leg on the Somme shortly after midnight on 11 June 1916, and left barely able to crawl, a corporal hoisted him on his back until a major saw what he was doing and told him:

‘“Drop the bugger here” for stretcher-bearers to find. If every wounded man were to be carried back, their firepower would be cut in half. “Don’t you know there’s a sod of a war on?”’ [16]

Many of the seriously wounded stumbled or crawled into shell-holes to wait for their rescuers; some lay out for days. On the first day of the Somme Pte A. Matthews was escorting German prisoners back across No Man’s Land, that narrow strip between the opposing lines of trenches, when he was shot in the thigh. An officer dragged him into a disused trench and bound up his wound as best he could before rejoining the advance. While the trench sheltered Matthews from direct fire (‘shells were bursting all around me’), he realised that unfortunately it also concealed him from the view of any rescuers. Later that day a company runner chanced to see him and left his water-bottle, but Matthews was unable to move – ‘I might as well have been chained to the ground’ – and as night fell all he could do was shout for help. Nobody came. He eked out his iron rations and water, but by the third day it was all gone. The next night a group of wounded men making their way back found Matthews, and shared the iron rations they had scavenged from the dead. They could do no more for him, but promised to get help. An hour or two later they returned, disoriented, and set off in a different direction. The next night they came back again, ‘in a terrible state’, one of them crawling on his hands and knees. They shared some biscuits and water before setting out once more; Matthews never saw them again. The next morning a shell-burst buried the biscuits and pierced his water-bottle, and he was reduced to catching rain in his helmet and drinking from pools of water in the trench. He drifted in and out of consciousness until, ten days later, an officer on patrol found him – ‘nearly treading on me’ – and dug him out before getting him onto a stretcher. When he reached the Advanced Dressing Station at Sailly he was ‘a mere skeleton’: he had been lying out in No Man’s Land for 14 days. [17] This was something of a record; Matthews’s experience combines bad luck and good luck in equal measure, and it is impossible to know how many others succumbed to their injuries while waiting or, perhaps like the party of wounded men who stumbled back to his trench time and time again, never made it to safety.

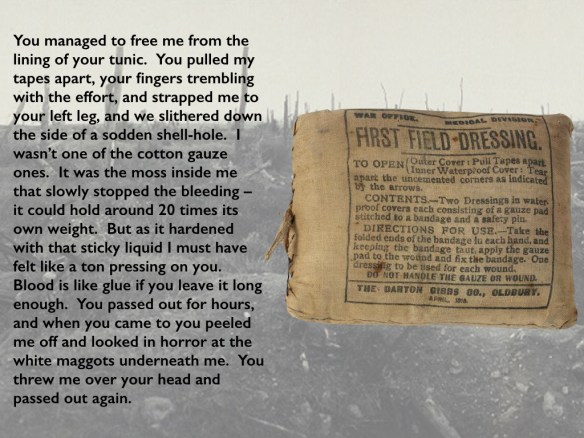

If they were fortunate the wounded would have others for comfort and company while they waited, but all any of them had for first aid was a field dressing and an ampoule of iodine. Capt Harold McGill reckoned that ‘the obsessing fear of the men was death from hemorrhage’ – understandably so in the absence of effective blood transfusion until late in the war – and the field dressing was the first vital response to bring bleeding under control. [18] One soldier explained:

‘The first field dressing which each man carries sewn in the lining of his tunic has saved many lives. Comprising as it does two pads of gauze and cotton-wool and a bandage, it can be ripped out of its case and clapped on to the wound, and so save the injured man, who may have to lie out hours before he can be taken back to a dressing-station, many risks from loss of blood or outside infection.’ [19]

Of course, the utility of the dressing depended on the nature of the wound. The same man recalled a lecture from his Medical Officer, who had explained that a field dressing could be used to stop bleeding from an arm or a leg, but ‘if the man was hit in the body or head – well, the doctor shrugged his shoulders in a way that made us think.’ [20]If they were not alone the wounded might also be able to improvise a tourniquet or even a splint with their bayonet or rifle, and if the iodine bottle had not smashed – unlikely, McGill thought: ‘The men reported to me that during the action they had nearly always found their pocket ampoules of iodine tincture broken when the time came to use them’ [21]– they could make a rudimentary attempt at cleaning the wound.

Given the cascading combination of immediacy, difficulty and uncertainty it is scarcely surprising that the space of the wounded should have contracted so drastically. And yet at the same time that space expanded, partly through what had become the taxing task of traversing even a short distance to relative safety, and partly through the tantalizing prospect of a ‘Blighty’, a wound judged sufficiently serious to require evacuation to Britain (and perhaps beyond for troops who came from elsewhere in the Empire). [22]

Arthur Empey came round from surgery at a Casualty Clearing Station to find rows of soldiers lying on stretchers: ‘The main topic of their conversation was Blighty. Nearly all had a grin on their faces.’ [23] One medical orderly explained that ‘a wound, even when serious, is the messenger of freedom’ – and he had never met a wounded man who wanted to return to the trenches. [24]Another had ‘only heard of one who said that he was anxious to return there, and he was subsequently transferred to No. 2 General Hospital in Le Havre, where the huge numbers of mental cases were cared for.’ [25]

Even so, the extended space of evacuation was a fraught and dangerous one. Many of the wounded fell in No Man’s Land, in the front-line trenches themselves, or in broken land during the fluctuating tides of advance and retreat in the opening and closing phases of the war. They were injured in major offensives (‘pushes’), in small raids (‘stunts’) and by routine, almost ritualized shelling and firing (‘the morning hate’). These were the most immediate danger zones in space and in time, extending back towards the reserve trenches and the small towns and villages in the rear. The wounded were supposed to move within a legal envelope that protected them from further attack. The Hague Regulations stipulated that ‘all necessary steps must be taken to spare’ – as far as possible – ‘places where the sick and wounded are collected.’ But that possibility was none the less limited. Firing and shelling were often notoriously inaccurate, casualty clearing stations were routinely located close to batteries and railheads, and it was not always easy to make out the red cross symbol that was supposed to guarantee protection. In the final months of the war even base hospitals on the French coast were bombed, while hospital ships crossing the Channel ran the gauntlet of mines and torpedoes. [26] If the wounded imagined travelling through an extended space towards safety, then it was a safety rendered conditional by the continued risk of attack. And the journey itself always exacted its own, sometimes deadly toll on the wounded body, which prompted Patrick MacGill to write of being ‘a passenger on the Highway of Pain that stretched from Lens to Victoria Station’. [27]

My purpose is to reconstruct that highway and the relationship between wounded bodies and the journeys they undertook. Many of those planning for war had a remarkably sanitized view of both. When one hard-pressed volunteer with the British Red Cross Society, working at a field hospital in Belgium in September 1914, described her pre-war training she recalled

‘the drill and the white-capped stretcher-bearers at home, and the little messenger boys with their innocuous wounds, which were so neatly and laboriously dressed.

The messenger boys’ wounds were always conveniently placed, and they never screamed and writhed or prayed for morphia when they were being bandaged. And shoulders were not shot away, nor eyes blinded, nor men’s faces – well, not much good ever came of talking of the things one has seen, and they are best left undescribed. “These are not wounds, they are mush,” I heard one surgeon say; and then I thought of the little messenger boys and their convenient fractures.’ [28]

The wounds were not the stylised, artfully coloured images of the text book and when G.H. Makins suggested that a survey of them ‘forcibly reminds the observer of the water-colour drawings made by Sir Charles Bell’ he was referring to Bell’s extraordinary ability to convey the horrific damage wrought by musket balls and shrapnel during the Peninsular War. Bell was a military surgeon and his sketches were no less remarkable for their rendering of the agony, despair and sheer terror of the wounded: a far cry, as he noted, from the text-books. [29]

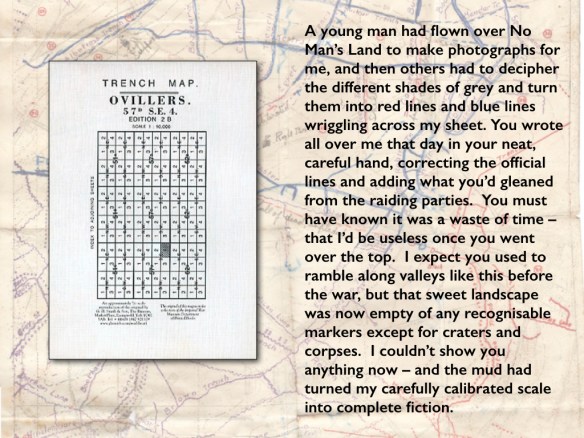

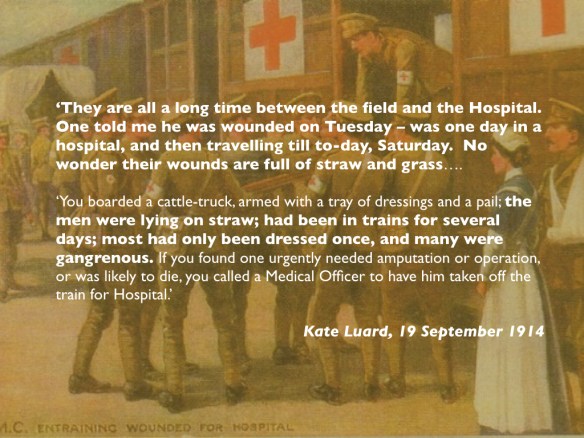

Similarly, schemes for medical evacuation typically displayed an elegant linear geometry, an abstract grid of transmission lines that resembled what Fiona Reid called ‘a modernist dream’ with no catastrophic breaks or nightmare tangles (Figure 3). [30] This highly imaginative geography of an evacuation machine, carefully oiled and smoothly running, intersected with debates around a politics of speed. [31] [For much more, and a detailed case study, see my post on ‘The Leaden Hours’ here]. In the first months of the war there were complaints that it was taking far too long for the wounded to be brought from the firing zone to hospitals on the French coast. These reports provoked sufficient public unease for Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, to send Col Arthur Lee to France to investigate. In a series of private communications Lee conceded that ‘in surveying the scene from London, or studying it upon a map, questions of transport present no very serious difficulties’, whereas once in France it quickly became obvious that getting the wounded to railheads was complicated by intense enemy shelling, and that the railways were under enormous pressure – ‘the wounded must of course give way to food, ammunition and reinforcements for the fighting forces’ – and with many bridges destroyed and signalling systems dislocated the hastily improvised ambulance trains, often little more than cattle trucks filled with straw, had ‘to slowly explore their own way back towards [the hospitals at] the Base.’ [32] Two years later the politics of speed had reversed; the concern now was that the RAMC had become so fixated on rapid evacuation that the injured were suffering needlessly. The debate reached its climax when Sir Almroth Wright, Consultant Physician to the British Expeditionary Force, criticized what he saw as the preoccupation with rapid evacuation, ‘hustling the wounded from hospital to hospital’ he called it, and the overwhelming importance attached to ‘the fact that a [Casualty Clearing Station] has passed so many thousands or tens of thousands of wounded through the wards, evacuating these in a minimum of time so as to be at disposal for reception of more patients.’ He claimed that as soon as a new convoy arrived at a base hospital, and as a direct result of ‘the catastrophes which are associated with long journeys’ from the Casualty Clearing Station, ‘amputations and other operations in large numbers have to be performed upon men who had been judged fit to travel’ (my emphasis). Wright’s complaints were summarily – and angrily – dismissed as ignorant and even ‘stupid’ in what was a bitter personal dispute, and the official response doubled down on the machine-like efficiency of the evacuation system.

What flickers in the fissures of these exchanges is the stubbornly, viscerally bio-physical: injured bodies did not present themselves as pristine plates in a medical atlas and their precarious journeys were not inscribed on the paper trails of an evacuation plan. The relations between the two were not only intimate; they were also reciprocal. The nature of the wound materially affected evacuation. Treatment times and pathways for ‘walking wounded’ and stretcher-cases were different, for example, and the worst cases were often the last to reach a Casualty Clearing Station and – if they survived – they travelled much further down the line and ultimately back to Britain. Those journeys in turn affected the wound: rescuing casualties from No Man’s Land was almost always at the risk of further injuries from enemy fire, for example, and as bearers struggled to carry stretchers over shell-shattered ground and through waterlogged trenches, as ambulances bumped and skidded over muddy tracks and torn-up roads, and as ambulance trains clanked and wheezed their way to the coast, the spasmodic jolting greatly aggravated pain and increased the risk of haemorrhage.

To be continued

[1]John Keegan, The Face of Battle(London: Pimlico, 2004), p. 40; Keegan was referring specifically to General Sir William Napier’s account of the battle of Albuera in 1811, but he was also sharpening a general point.

[2]Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: the making and unmaking of the world (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985) p. 64.

[3]Regiments were raised from other British colonies in the Caribbean and Africa too, and also in Newfoundland; in some cases colonial and imperial casualties were treated by their own medical services, and in others by the RAMC, though they all worked in close concert with one another. For a general discussion, which extends to the French and German medical services, see Leo van Bergen, Before my helplesssSight: suffering, dying and military medicine on the Western Front, 1914–1918 (London: Routledge, 2016).

[4]On ‘shell shock’ and, of direct relevance to my discussion, what was known as ‘wound shock’, see Stefanos Geroulanos and Todd Myers, The human body in the age of catastrophe: brittleness, integration, science and the Great War(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018) especially Ch. 2.

[5]Casualty estimates are notoriously difficult, but on the Western Front more than five million from the Allied armies were wounded, most of them from France and the United Kingdom, and more than three million from the Central Powers, principally Germany and Austria-Hungary. There were also tens of thousands of civilian casualties, from towns and villages close to the front lines but also from long-distance shelling and air strikes much more distant from battlefields whose boundaries were already dissolving.

[6]Captain A. Radclyffe Dugmore, When the Somme ran red(New York: George H. Doran, 1918) pp. 201-2. Hence too Mark Harrison’s apt description of a ‘medical machine’ assembled on the Western Front: The Medical War: British Military medicine in the First World War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010). The imagery of two streams was a common one too, and so was its mechanical rendering. ‘One of the most stabbing things in this war,’ wrote Sister Kate Luard, ‘is seeing the lines of empty motor ambulances going up to bring down the wrecks who at this moment are sound and fit, and absolutely ready to be turned into wrecks’: John Stevens (ed) Unknown warriors: the letters of Kate Luard1914-1918(Stroud, UK: History Press, 2014) 8 May 1915.

[7]Stevens, Unknown warriors, 10 April 1917; Ward Muir, ‘An intake of wounded’, in Happy though wounded: the book of the 3rdLondon General Hospital(London: Country Life, 1917) p. 64.

[8]H.G. Hartnett, Over the top(Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2009) p. 60; Hartnett wrote his memoir in the early 1920s from diaries he had kept during the war.

[9]His own journey was a long and painful one. ‘After tramping five or six miles in search of medical attention,’ Hartnett continued, he and his mates ‘finally reached Albert, where the confusion was even worse if that was possible. Long lines of wounded men along the footpaths and roadways were waiting their turn to get attention from doctors and their assistants, stationed at intervals along the roads, out in the open’ (p. 61). From Albert he was taken by lorry and light railway to a casualty clearing station and, after his wound had been dressed, by ambulance train to Rouen; then it was on to Le Havre and a hospital ship bound for Southampton.

[10]Wilfred Owen, Collected Letters(ed. Harold Owen and John Bell) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967) 31 December 1917; ‘An O.E.’ [G.P.A. Fildes], Iron times with the Guards(London: John Murray, 1918) pp. 74-5; Lawrence Gameson, Private Papers, IWM Doc 612; Philip Gibbs, Now it can be told(New York: Harper, 1920) p. 374; Capt Leonard Pearson, in Lyn MacDonald, The Roses of No Man’s Land(London: Penguin, 1993) p. 187.

[11]Edward G.D. Living, Attack: An Infantry Subaltern’s Impression of July 1st, 1916 (New York: Macmillan, 1918) pp. 69-70. He managed to walk out after one of his men applied iodine and a field dressing to his wound, but walking became steadily more painful; eventually, weak from loss of blood, he was placed on a stretcher and wheeled to an advanced dressing station, and from there he was taken by ambulance to a Casualty Clearing Station.

[12]R.H. Tawney, ‘The attack’, Westminster Gazette, 24-5 October 1916.

[13]Graves confessed that his memory of what happened next was ‘vague’. He was not expected to survive, and was taken to a dressing station where he remained unconscious; when his commanding officer went down and saw him lying in a corner ‘they told him I was done for.’But the next morning an ambulance took Graves to a Casualty Clearing Station, where he remained until 24 July when he was put on an ambulance train for a Base Hospital on the coast and was eventually repatriated to Britain. Meanwhile his commanding officer had written to his mother tendering his condolences at the loss of her son. Robert Graves, Goodbye to all that (London: Penguin, 2000; first published in 1929) pp. 180-2.

[14]Siegfried Sassoon, Memoirs of an infantry officer(London: Faber, 1930). This is a fictionalised account of Sassoon’s experience on 16 April 1917; he recorded his more immediate reactions in his journal but said virtually nothing about the initial shock of being hit. He left the trench as ‘walking wounded’ and, after his wound was dressed at an aid post, was driven to a Casualty Clearing Station: Sassoon Journal, Cambridge University Library MS Add. 9852/1/10.h

[16] Jones resumed his crawl and was eventually found by a bearer party: Thomas Dilworth, David Jones and the Great War (London: Enitharmon Press, 2012) p. 117. Tiplady, Soul of the soldier, p. 131 explained the logic behind the injunction: ‘When a man falls his neighbor cannot stay with him. He must press on to the objective, otherwise, if the unwounded stayed to succor the wounded, there would be none to continue the attack.’ This was of course emotionally hard. ‘The grimmest order to me was that no fighting soldier was to stop to help the wounded,’ one sergeant confessed. ‘The CO was very emphatic about this. It seemed such a heartless order to come from our CO who was … looked upon as a religious man. I thought bringing in the wounded was the way Victoria Crosses were won. But I realized that this would be an order to the CO as well as us from the General and that the whole of the attack could be held up if there were many wounded and we stopped to help them’: Sgt Charles Moss, in Richard van Emden, The Somme(Barnsley UK: Pen and Sword, 2016) p. 00.

[17]A. Matthews, ‘I was fourteen days in No Man’s Land’, I Was There!pp. 688-691; Capt A.W. French, War Diary (Liddle Collection), 14 July 1916. For another vivid account of a survivor, see the memoir written after the war by John Stafford describing his wounding on the Somme on 8 August 1916:https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/record/2020601/contributions_3155.html?q=%22John+Stafford%22.

[18]McGill, Medicine and Duty, pp. 118-9.

[19]Arthur Mills, Hospital Days(London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1916) p. 14.

[21]McGill, Medicine and Duty, p. 157.

[22]‘Blighty’, a corruption of the Urdu vilayati(‘foreign’ or ‘European’) was first used by Indian soldiers to refer to Britain in the Boer War; its use became widespread in the First World War.

[23]Arthur Empey, Over the top(New York: G.P. Putnam, 1917) p. 00.

[24]Christopher Arnander (ed), Private Lord Crawford’s Great War Diaries(Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword, 2013) 30 September 1915. ‘To these men,’ Crawford added, ‘the relief of leaving the front honourably wounded is inconceivable after months of killing, anxiety and fatigue.’ David Lindsay, the Earl of Crawford, enlisted in the RAMC as a private in April 1915 at the age of 43; in July 1916 he returned to the UK as a member of the coalition government.

[25]M.R. Werner, Orderly!(New York: Jonathan Cape & Harrison Smith, 1930) p. 76.

[26]Stephen McGreal, The war on hospital ships, 1914-1918(Barnsley UK: Pen and Sword, 2009).

[27]Patrick MacGill, The Great Push: an episode of the Great War(New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1916) p. 254. This was a memoir lightly disguised as fiction; MacGill was wounded at Loos on 28 September 1915, and in the preface wrote that he had ‘tried to give, as far as I am allowed, an account of an attack in which I took part’ (p. 7).

[28]Sarah Macnaughtan, A woman’s diary of the war(London: Nelson, 1916) p. 23. Similar make-believe drills took place behind the front lines, where they were met with a healthy cynicism by ‘wounded’ and stretcher bearers alike. ‘After heavy losses we would get reinforcements and this would be followed by a Field Day to break in the newcomers’, explained one orderly with a Field Ambulance. ‘Men with labels describing their supposed injuries were hidden in unlikely spots and had to be found and dealt with as if actually wounded’: Edwin Ware, Diary,p. 94 [WL:RAMC/PE/1/707]. One private recalled a rehearsal for a ‘special stunt’ in which he played a casualty: ‘My wounds were not too painful to prevent my enjoyment of the spectacle while waiting for the stretcher bearers, who did not seem in a great hurry. Casualties here had their own choice of wounds, and they all seemed to prefer some wound which made it impossible to walk a step, much to the disgust of the stretcher bearers.After some argument with the stretcher bearers who came at last to attend to me, I was bundled unceremoniously on to a stretcher with my mess tin making itself unpleasant in the middle of my back, despite the fact that both my legs had been shattered (in theory)’: Doreen Priddey (ed.), A Tommy at Ypres: Walter’s War(Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2011) 5-9 December 1916.

[29]G.H. Makins, ‘A note upon the wounds of the present campaign’, The Lancet, 10 October 1914 (p. 905); M.K. H. Crump and P. Starling, A surgical artist at war: the paintings and sketches of Sir Charles Bell 1807-1815 (Edinburgh: Royal College of Surgeons, 2005). Bell uncannily prefigured the horrors for which his successors were equally ill-prepared one hundred years later. ‘The cases I have had under my care,’ he wrote in his Dissertation on gunshot wounds(1814), ‘have proved to me that the books we possess upon the subject of field-practice do not even hint at the nature of the difficulties the surgeon has to encounter there.’

[30]Fiona Reid, Medicine in First World War Europe: Soldiers, Medics, Pacifists (London: Bloomsbury, 2017) p. 19.

[31]Derek Gregory, ‘The politics of speed and casualty evacuation on the Western Front, 1914-1918’, forthcoming.