Just as I started to think about the Annual Lecture I have to give at the Kent Interdisciplinary Centre for Spatial Studies (KISS) next month, on the spaces of modern war, I stumbled across a splendidly angry and wonderfully perceptive new essay from Achille Mbembe on ‘Deglobalization‘ at Esprit (via Eurozine), 18 February 2019:

Just as I started to think about the Annual Lecture I have to give at the Kent Interdisciplinary Centre for Spatial Studies (KISS) next month, on the spaces of modern war, I stumbled across a splendidly angry and wonderfully perceptive new essay from Achille Mbembe on ‘Deglobalization‘ at Esprit (via Eurozine), 18 February 2019:

The spare abstract doesn’t begin to do it justice:

Digital computation is engendering a new common world and new configurations of reality and power. But this ubiquitous, instantaneous world is confronted by the old world of bodies and distances. Technology is mobilized in order to create an omnipresent border that sequesters those with rights from those without them.

The essay opens with some characteristically perceptive insights into digital computation (which Achille understands in three distinct but related ways) and its world-creating and world-dividing capacities, but given my KISS Lecture, I was much taken with this passage describing what Achille calls ‘borderization‘:

What is borderization if not the process by which world powers permanently transform certain spaces into places that are impassable to certain classes of people? What is borderization if not the deliberate multiplication of spaces of loss and grief, where so many people, deemed undesirable, see their lives shatter into pieces?

What is it, if not a way to wage war against enemies whose living environments and chances of survival have already been devastated? The use of uranium armour-piercing ammunition and prohibited weapons like white phosphorus; the high-altitude bombardment of basic infrastructure; the cocktail of carcinogenic and radioactive chemical products deposited in the soil and filling the air; the toxic dust raised by the ruins of obliterated towns; the pollution emitted by hydrocarbon fires?

And what about the bombs? Is there any type of bomb that has not been dropped on civilian populations since the last quarter of the twentieth century? Classic dumb bombs repurposed with tail-mounted inertial measurement units; cruise missiles with infrared seekers; microwave bombs designed to paralyze the enemy’s electronic nerve centres; other microwave bombs that do not kill but burn skin; bombs that detonate in cities releasing energy beams like bolts of lightning; thermobaric bombs that unleash walls of fire, suck the oxygen out of more or less confined spaces, send out deadly shockwaves and suffocate anything that breathes; cluster bombs that explode above the ground and scatter small shells, designed to detonate on contact, indiscriminately over a wide area, with devastating consequences for civilian populations; all sorts of bomb, a reductio ad absurdum demonstration of unprecedented destructive power – in short, ecocide.

Under these circumstances, how can we be surprised when those who can, those who have survived living hell, try to escape and seek refuge in any and every corner of Earth where they might be able to live safely?

This form of calculated, programmed war, this war of stupefaction with its new methods, is a war against the very ideas of mobility, circulation and speed, despite the fact that we live in an age of velocity, acceleration and ever more abstraction, ever more algorithms.

Its targets, moreover, are not singular bodies; they are entire human masses who are dismissed as contemptible and superfluous, but whose organs must each suffer their own specific form of incapacitation, with consequences that last for generations – eyes, nose, mouth, ears, tongue, skin, bones, lungs, gut, blood, hands, legs, all the cripples, paralytics, survivors, all the pulmonary diseases like pneumoconiosis, all the traces of uranium found in hair, the thousands of cancers, miscarriages, birth defects, congenital deformities, wrecked thoraxes, nervous system disorders – utter devastation.

All these things, it bears repeating, are connected to contemporary practices of borderization being carried out remotely, far away from us, in the name of our freedom and security. This conflict against specific bodies of abjection, mounds of human flesh, unfolds on a planetary scale. It is poised to become the defining conflict of our time.

Achille then connects this to Grégoire Chamayou‘s arguments about ‘manhunts’ (see my discussion of ‘the individuation of warfare’ here – though, like Achille, I’d now insist that ‘individuation’ is only one modality of later modern war and that, as I’ve suggested here, aerial violence and siege warfare both continue to target ‘the social’, those ‘entire human masses’):

This conflict often precedes, accompanies or supplements the other conflict being waged in our midst or at our doors: the hunt for bodies that have been foolish enough to move (movement being the essential property of the human body); bodies judged to have forced their way into places and spaces where they have no business being, places they clog up by simply existing, and from which they must be expelled.

As the philosopher Elsa Dorlin remarks, this form of violence is directed towards prey. It resembles the great hunts of the past – tracking and pursuing, laying traps and beating, and finally surrounding, capturing or slaughtering the quarry with the help of pack hounds and bloodhounds. It fits into a long history of manhunts. Grégoire Chamayou studies their various manifestations in Manhunts: A Philosophical History. They always involve the same sort of quarry – slaves, aborigines, dark skins, Jews, the stateless, the poor and, closer to home, the undocumented. They target animate, moving bodies that, marked out and ostracized, are seen as entirely different from our own bodies despite being endowed with attractive force, intensity, the capacity to move and flee. These hunts are taking place at a time when technologies of acceleration are proliferating endlessly and creating a segmented, multi-speed planet.

And finally this:

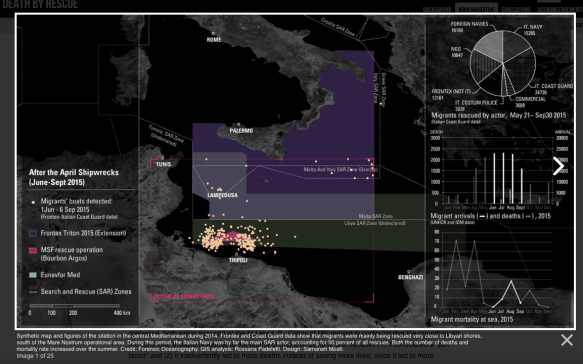

What is the deadliest destination for migrants in an increasingly balkanized and isolated world? Europe. Where lie the most skeletons at sea, where is the biggest marine graveyard at the beginning of this century? Europe. Where are the largest number of territorial and international waters, sounds, islands, straits, enclaves, canals, rivers, ports and airports transformed into technological iron curtains? Europe. And to crown it all, in this era of permanent escalation, the camps. The return of camps. A Europe of camps. Samos, Chios, Lesbos, Idomeni, Lampedusa, Ventimiglia, Sicily, Subotica – a garland of camps…. [I’ve taken the map below from ‘Camps in Europe’ here].

It bears repeating that this war (which takes the form of hunting, capturing, rounding up, sorting, separating and deporting) has one aim. It is not about cutting Europe off from the world or turning it into an impenetrable fortress. It is about arrogating to Europeans alone the rights of possession of and free movement around a planet that rightfully belongs to all of us.

I’m not sure about all of this, not least because that precious right of ‘free movement’ within Europe is precisely what is being called into question by the resurgent right across Europe. But there is much to think about here, and I urge you to read the whole, brilliant essay.