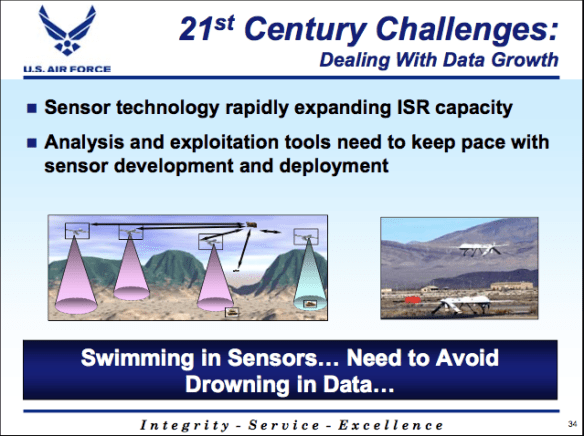

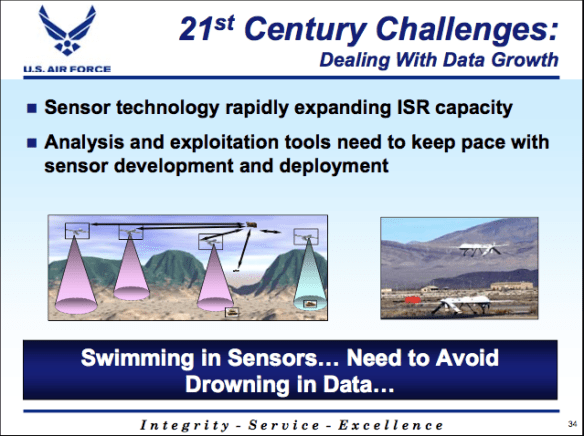

When he was the US Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) Lt Gen David Deptula frequently warned about the danger of ‘swimming in sensors and drowning in data‘. He was talking about crossing what he saw as the divide between ‘industrial age’ and ‘information age’ warfare, and specifically about the extraordinary volumes of data captured as full-motion video feeds from Predators and Reapers:

Dan Gettinger provides an excellent overview in ‘Drone geography: mapping a system of intelligence’ here. But there are other systems of intelligence involved in these strikes and other forms of what Deptula called ‘data crush’.

Operating in close concert with real-time ISR carried out from these remote platforms are other modes of digital data capture, not least the panoply of communications intercepts carried out by the National Security Agency. In many cases the targets Air Force crews are tasked to track and ultimately to kill by the CIA or the US military have been identified through SIGINT (signals intelligence) derived from ‘harvesting’ e-mails, text messages and cell phone calls.

These have become increasingly important in today’s wars where the targets are often mobile. E-mails can provide a vector of likely locations to be watched from the air, while call and messaging data reveal general vectors of movement:

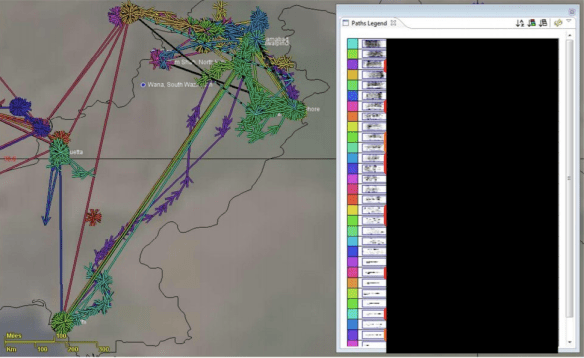

(The tracks above are taken from an NSA report on ‘SKYNET: Courier detection by machine learning’ released by The Intercept).

But it’s important not to misrepresent this as system of total surveillance: as Grégoire Chamayou insists, ‘it matters less to the NSA to actively monitor the entire world than to endow itself with the powers to target anyone – or, rather, whomever it wishes’ (what he calls ‘programmatic surveillance’).

It’s programmatic in several senses beyond the legal-political armatures that Chamayou initially emphasizes: it also implies, crucially, algorithmic executions. The software programs used by the NSA and associated agencies to tunnel into this data and extract signals from the noise are myriad – see for example this NSA white paper on ‘co-traveller analytics‘ – but even armed with these deadly algorithms (see also here) there is a concern about data crunch.

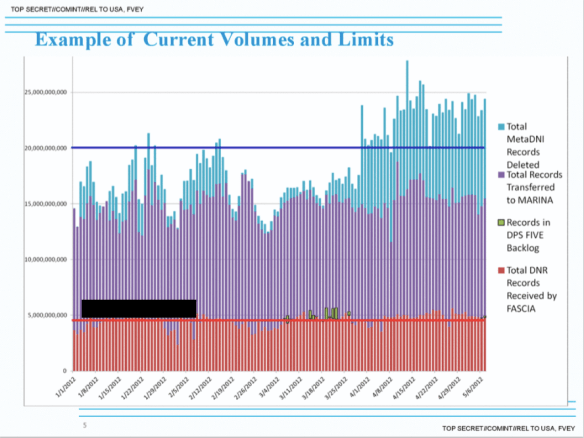

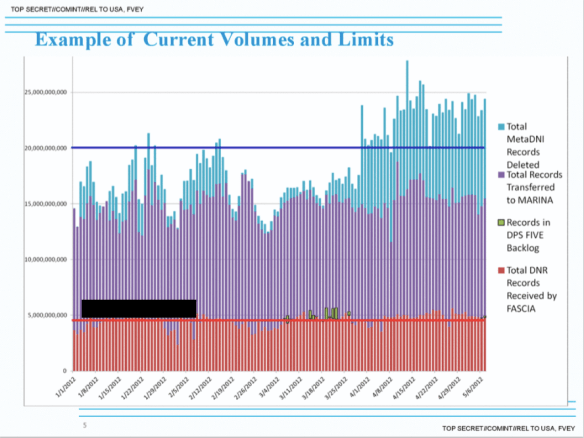

Writing in the Washington Post Ashkan Soltani and Barton Gellman reported that in 2012 FASCIA, the NSA’s databank, was ingesting almost 5 billion records a day:

Hence, as Peter Maass reports in The Intercept, the NSA’s own officers have become alarmed at rising metadata levels. In 2011, for example, a deputy director in the Signals Intelligence Directorate was asked about ‘analytic modernization’ at the agency

“We live in an Information Age when we have massive reserves of information and don’t have the capability to exploit it… I was told that there are 2 petabytes of data in the SIGINT System at any given time. How much is that? That’s equal to 20 million 4-drawer filing cabinets. How many cabinets per analyst is that? By the end of this year, we’ll have 1 terabyte of data per second coming in. You can’t crank that through the existing processes and be effective.”

I’m working my way through these files as part of my ‘Deadly dancing’ essay on targeted killing in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas. I’m particularly interested in the ways in which these two systems of digital capture – signals intercepts and video-feeds – intersect. On occasion, the two systems even become one: for example, the NSA’s GILGAMESH program relies on sensors attached to a Predator to track a cell phone to within 30 feet of its location while SHENANIGANS similarly ‘vacuums up massive amounts of data from any wireless routers, computers, smart phones or other electronic devices that are within range’.

In any event these two, closely connected systems of digital capture are also often the harbingers of a physical kill. As Michel Hayden, former director of the NSA and the CIA, admitted to David Cole last year: ‘We kill people based on metadata.’

And the reliance on algorithms and the expert systems they animate ensures, as Louise Amoore insists, that ‘there is then nothing exceptional about the exception; they are derogated to and derive from “expert knowledges”.’

As Louise’s comment implies, all of this speaks directly to the FATA as a space of exception, and the first section of my essay treats its production in detail (you can find early sketches here and here); but in the second section I connect this to the FATA as a space of execution. Formally, I suppose this and its derivative expert knowledges parallel Stuart Elden‘s suggestion that territory be treated as a political technology, but the space of execution (like the space of exception) has a paradoxical topology since here and elsewhere its calculus enables the United States to enact an extra-territorial claim over the territory of another sovereign state.

Drone strikes in the FATA then appear as the deadly tip of an extended spear, the product of a dense network of collaboration and calculation between the CIA (which directs the strikes), the NSA and its associated agencies (which provide the geospatial intelligence), and the US Air Force (which executes them).

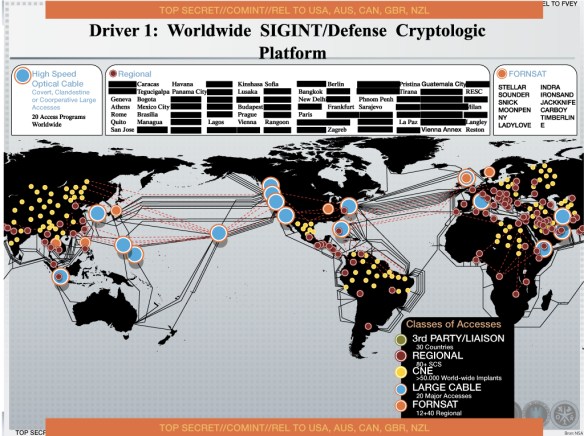

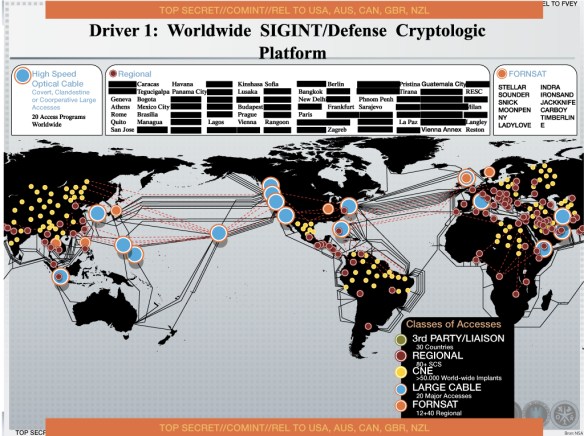

The intelligence component of the network is transnational. There is a long history of often fraught collaboration between the CIA and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, and the NSA also derives what it calls ‘locational intelligence’ from its Five Eyes partners – the UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand – and its Tier II partners which are contracted for specific projects and paid for their services: an NSA document for 2013 in the Snowden cache shows that this includes Pakistan, but it is impossible to know when this contractual relationship started and whether it has been discontinued.

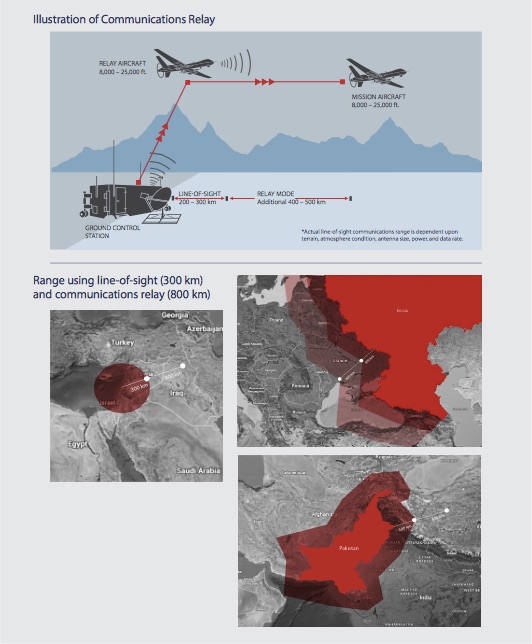

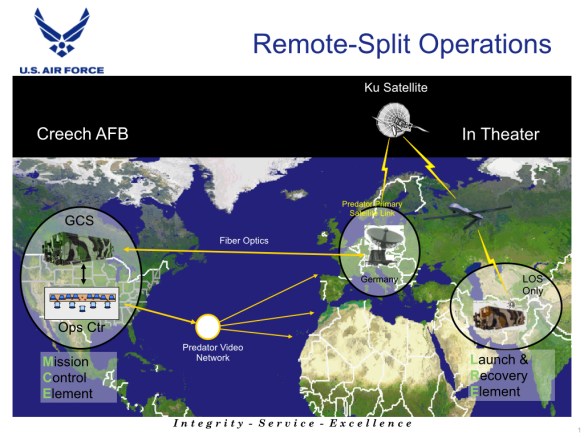

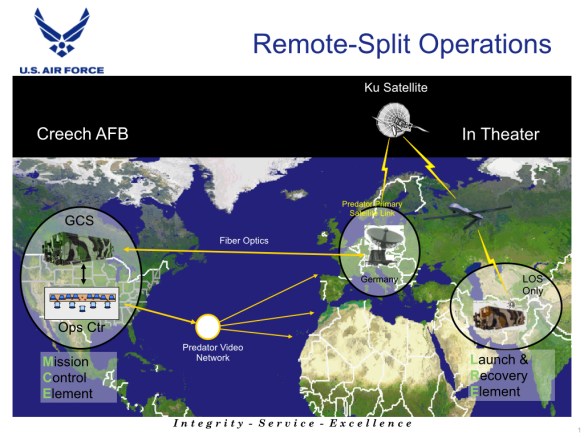

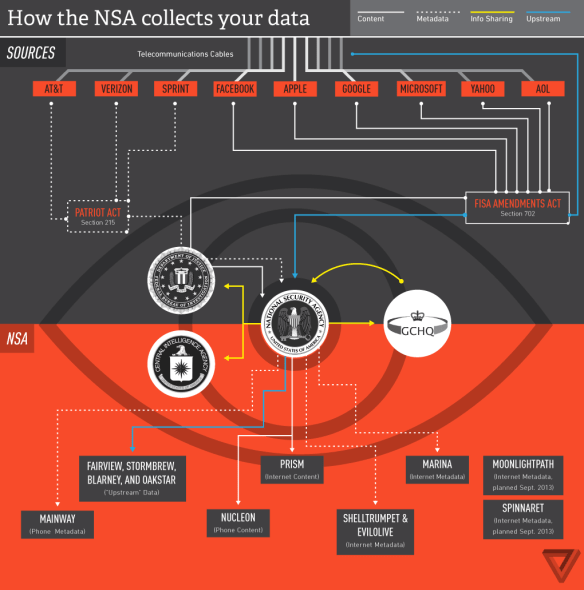

The NSA also conducts a version of ‘remote split’ operations. Just as Predators and Reapers are controlled from the United States via satellite link and fiber-optic cable (once forward deployed crews have handled the take-off) – see the slide above – so much of the NSA’s interception and analysis of global communications takes place in the United States, harvesting data through two overarching systems:

1 Intercepts of foreign communications from submarine fiber-optic cables, the physical channels of the web; these are UPSTREAM intercepts conducted ‘as data flows past’ under legal authorizations that flow from Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA: passed under Bush and extended under Obama and permits the monitoring of electronic communications of foreigners abroad); some take place at more than a dozen switching stations within the US, exploiting its pole position within the web, while the rest take place overseas, often in conjunction with other intelligence services (FVEY and Tier II ‘Third Parties’); multiple software programs [FAIRVIEW, BLARNEY, STORMBREW, OAKSTAR] are used to harvest the data, which together amount to c. 9 per cent of Internet traffic collected under S702.

You can also find a stunning interactive map that attempts to annotate the submarine cable intercepts based on the Snowden cache here.

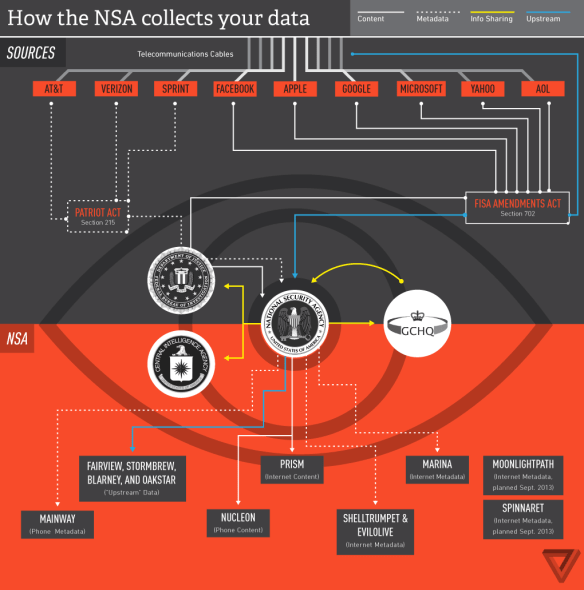

2 Direct collection of data from servers of major Internet companies and corporations (Google, Microsoft, AOL, Skype etc) in response to demands under S702 that requires ISP to turn over any data matching court-approved search terms; these are DOWNSTREAM intercepts because the data has already been collected by the companies (un)concerned; the data include e-mails and social network activity, and together these intercepts are the major source of raw intelligence, accounting for 91 per cent of Internet traffic collected under S702. The chart below from The Verge refers to the NSA collecting ‘your’ data but the ‘you’ is a global collective. PRISM – ‘the code name for a data-collection effort known officially by the SIGAD US-984XN…. that collects stored Internet communications based on demands made to [US] Internet companies’ started in 2007; this too exploits what the NSA calls the US’s position as ‘the world’s telecommunications backbone.’

1 and 2 provide DNI data [Digital Network Intelligence]; but 1 also allows the harvesting of DNR data [Dialed Number Recognition] and, according to a PRISM briefing slide dated April 2013, is ‘coming soon’ to 2 (PRISM).

According to Boundless Informant, an NSA collection visualisation tool, during a 3-day period ending in March 2013 DNI intercepts from Pakistan accounted for 13.9 per cent of global DNI intercepts (#2 after Iran, which accounted for 14.5 per cent) and 11.1 per cent of global DNR intercepts (#2 after Afghanistan, which accounted for 17.6 per cent). Aggregating the two – shown on the map below – Pakistan was the state subject to the most intense interception during that period (12.3 per cent of all global DNI and DNR intercepts).

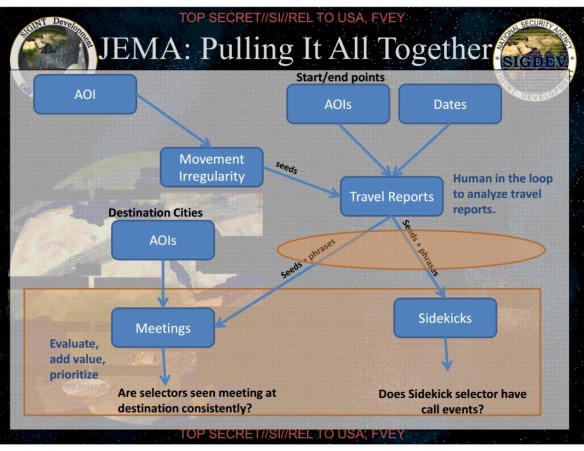

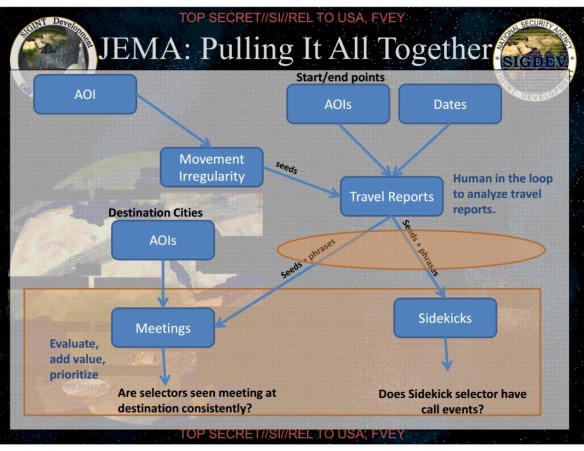

DNR is vital for drone strikes, since these so often depend on tracking cell-phones to identify the target in motion — see my post here — and for this reason the NSA has also forward deployed tactical cells working in close concert with military SIGINT units at (for example) Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. In short, its operations are not only ‘remote’ and are clearly ‘split’. These intercepts are often of direct and immediate utility, but bulk collections of call data records from (for example) Pakistan Telecom providers are also mined via SKYNET to identify suspects and convert them into targets via ‘Joint Enterprise Modelling and Analytics’ (JEMA) [AOI in the slide below refers to Area/Actor of Interest].

It is this combination of the transnational and the local – which parallels the network in which those flying the Predators and Reapers are embedded – that characterises what Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge call code/space:

‘Given that many of these code/spaces are the product of coded infrastructure, their production is stretched out across extended network architectures, making them simultaneously local and global, grounded … in certain locations, but accessible from anywhere across the network, and linked together into chains that stretch across space and time to connect start and end nodes into complex webs of interactions and transactions. Any space that has the latent capacity to be transducted by code constitutes a code/space at the moment of that transduction.’

‘Given that many of these code/spaces are the product of coded infrastructure, their production is stretched out across extended network architectures, making them simultaneously local and global, grounded … in certain locations, but accessible from anywhere across the network, and linked together into chains that stretch across space and time to connect start and end nodes into complex webs of interactions and transactions. Any space that has the latent capacity to be transducted by code constitutes a code/space at the moment of that transduction.’

As you can see from the subtitle, their primary interest is everyday life. But in the cases that most concern me, the conversion of everyday life into code/space is a precursor to everyday death.

In the FATA and elsewhere code/space is clearly a highly asymmetric field, as it is intended to be, but those who are summoned into presence within the space of execution – a process that Louise Amoore calls ‘the appearance of an emergent subject’, of ‘pixelated people’ that emerge on screens scanning databanks but who also appear in the crosshairs of a video display – are not wholly ignorant of what is taking place, of the ‘coding’ of their space. It is of course the case that crews can see without being seen, and Grégoire Chamayou has argued that ‘the fact that the killer and his victim are not inscribed in “reciprocal perceptual fields” facilitates the administration of violence’ because it ruptures what psychologist Stanley Milgram in his experiments on Obedience to authority called ‘the experienced unity of the act.’ And yet those who are living under drones have developed their own apprehensions; they have learned, in some small measure, how to counter their digital capture and to reduce their physical vulnerability.

On 7 July 2014, in an apparent response to the murder of three teenagers, Israel launched a major offensive against the Gaza Strip, lasting 51 days, killing 2145 Palestinians (578 of them children), injuring over 11,000, and demolishing 17,200 homes.