In another lifetime, or so it seems, I wrote a short essay on ‘The death of the civilian’ (DOWNLOADS tab), and I seem to have spent much of the intervening years developing those early ideas. So I’m thrilled to see an important new paper from Nicola Perugini and Neve Gordon, ‘Distinction and the Ethics of Violence: on the legal construction of liminal subjects and spaces’, available online now at Antipode:

This paper interrogates the relationship among visibility, distinction, international humanitarian law and ethics in contemporary theatres of violence. After introducing the notions of “civilianization of armed conflict” and “battlespaces”, we briefly discuss the evisceration of one of international humanitarian law’s axiomatic figures: the civilian. We show how liberal militaries have created an apparatus of distinction that expands that which is perceptible by subjecting big data to algorithmic analysis, combining the traditional humanist lens with a post-humanist one. The apparatus functions before, during, and after the fray not only as an operational technology that directs the fighting or as a discursive mechanism responsible for producing the legal and ethical interpretation of hostilities, but also as a force that produces liminal subjects. Focusing on two legal figures—“enemies killed in action” and “human shields”—we show how the apparatus helps justify killing civilians and targeting civilian spaces during war.

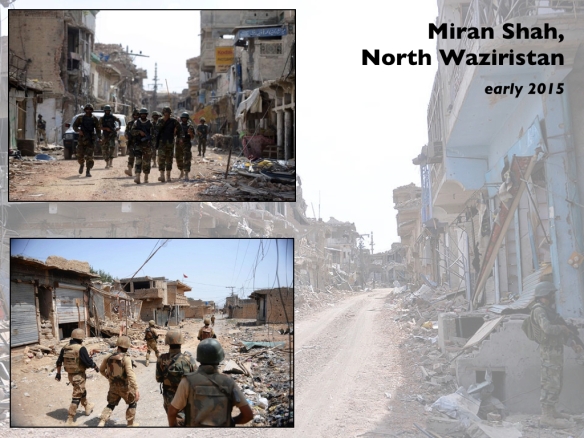

Their two case studies focus on US drone attacks in Pakistan and the use of human shields in Gaza (the image below, taken from the article, shows the Israeli Defence Force’s ‘Laboratory of Discrimination’ (sic)).

You can watch a video where Nicola and Neve discuss their ideas on the Antipode website here, which also provides a less formal gloss:

[Their paper] examines how militaries actually make distinctions in the battlefield, given that today most fighting takes place in urban settings where distinguishing between combatant and civilian is becoming increasingly difficult.

Their paper shows how liberal militaries are utilizing new technologies that aim to expand that which is perceptible within the fray. Combining the more traditional forms of making distinctions such as binoculars and cameras with cutting edge hi-tech, militaries subject big data to algorithmic analysis aimed at identifying certain behavioral patterns. The technologies of distinction function before, during, and after the fray not only in order to direct the fighting and to help produce the legal and ethical interpretation of hostilities, but also as a mechanism that identifies and at times creates new legal figures.

Focusing on two legal figures—“enemies killed in action” and “human shields”—Nicola and Neve show how technologies of distinction help justify killing civilians and targeting civilian spaces during war. Ultimately, they maintain that distinction, which is meant to guarantee the protection of civilians in the midst of armed conflict, actually helps hollow the notion of civilian through the production of new liminal legal figures that can be legitimately killed.

For more on the intersections between international law, military protocols and the (in)visibility of the civilian, I also recommend the insightful work of Christiane Wilke (see ‘Seeing Civilians (or not)’ here).