The Transnational Institute has published a glossy version of a chapter from Steve Graham‘s Vertical – called Drone: Robot Imperium, you can download it here (open access). Not sure about either of the terms in the subtitle, but it’s a good read and richly illustrated.

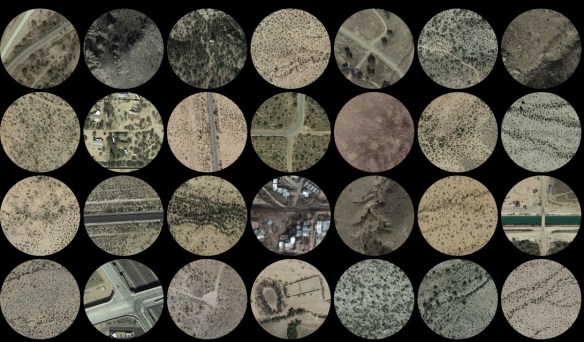

Steve includes a discussion of the use of drones to patrol the US-Mexico border, and Josh Begley has published a suggestive account of the role of drones but also other ‘seeing machines’ in visualizing the border.

One way the border is performed — particularly the southern border of the United States — can be understood through the lens of data collection. In the border region, along the Rio Grande and westward through the desert Southwest, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) deploys radar blimps, drones, fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, seismic sensors, ground radar, face recognition software, license-plate readers, and high-definition infrared video cameras. Increasingly, they all feed data back into something called “The Big Pipe.”

Josh downloaded 20,000 satellite images of the border, stitched them together, and then worked with Laura Poitras and her team at Field of Vision to produce a short film – Best of Luck with the Wall – that traverses the entire length of the border (1, 954 miles) in six minutes:

The southern border is a space that has been almost entirely reduced to metaphor. It is not even a geography. Part of my intention with this film is to insist on that geography.

By focusing on the physical landscape, I hope viewers might gain a sense of the enormity of it all, and perhaps imagine what it would mean to be a political subject of that terrain.

If you too wonder about that last sentence and its latent bio-physicality – and there is of course a rich stream of work on the bodies that seek to cross that border – then you might visit another of Josh’s projects, Fatal Migrations, 2011-2016 (see above and below).

There’s an interview with Josh that, among other things, links these projects with his previous work.

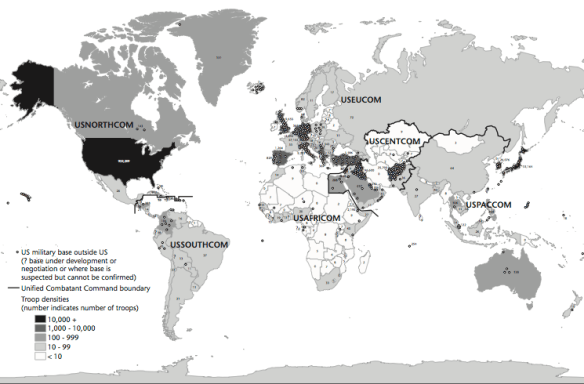

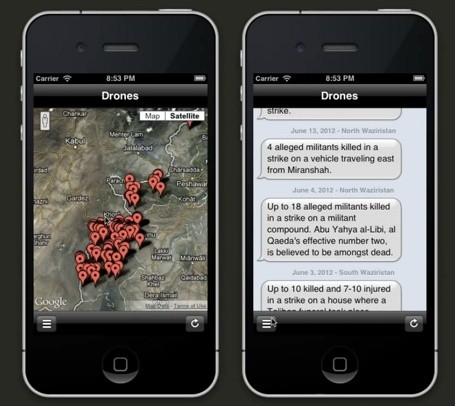

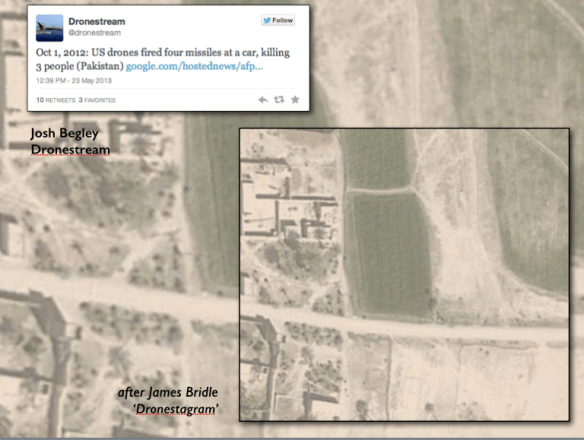

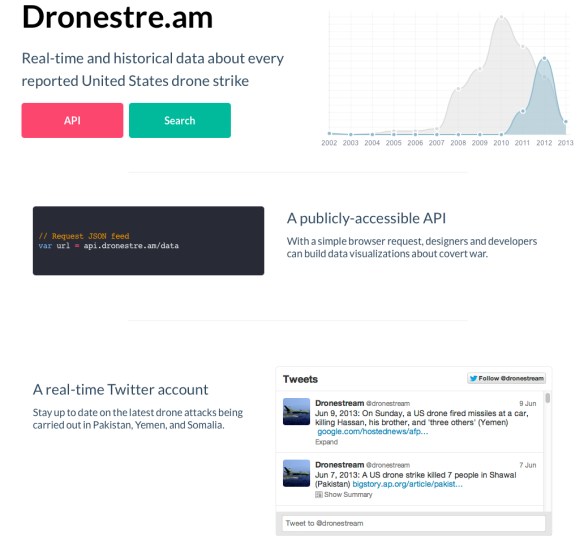

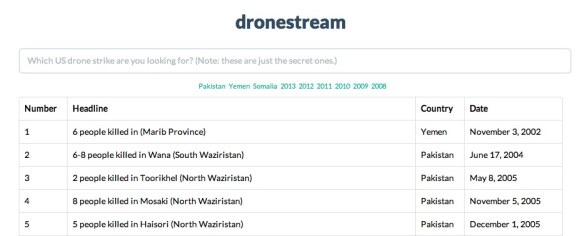

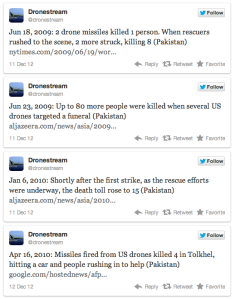

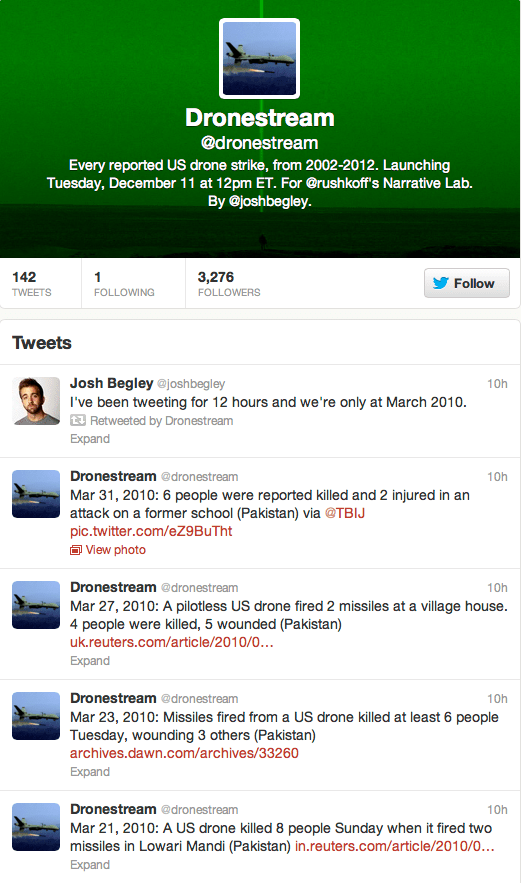

I have a couple of projects that are smartphone centered. One of them is about mapping the geography of places around the world where the CIA carries out drone strikes—mostly in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. Another was about looking at the geography of incarceration in the United States—there are more than 5,000 prisons—and trying to map all of them and see them through satellites. I currently have an app that is looking at the geography of police violence in the United States. Most of these apps are about creating a relationship between data and the body, where you can receive a notification every time something unsettling happens. What does that mean for the rest of your day? How do you live with that data—data about people? In some cases the work grows out of these questions, but in other cases the work really is about landscape….

There’s just so much you can never know from looking at satellite imagery. By definition it flattens and distorts things. A lot of folks who fly drones, for instance, think they know a space just from looking at it from above. I firmly reject that idea. The bird’s eye view is never what it means to be on the ground somewhere, or what it means to have meaningful relationships with people on the ground. I feel like I can understand the landscape from 30,000 feet, but it is not the same as spending time in a space.

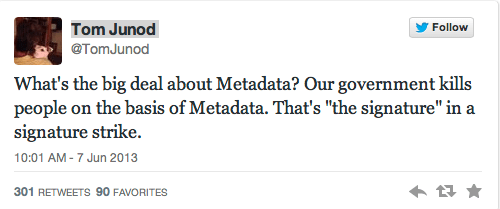

Anjali Nath has also provided a new commentary on one of Josh’s earlier projects, Metadata, that he cites in that interview – ‘Touched from below: on drones, screens and navigation’, Visual Anthropology 29 (3) (2016) 315-30.

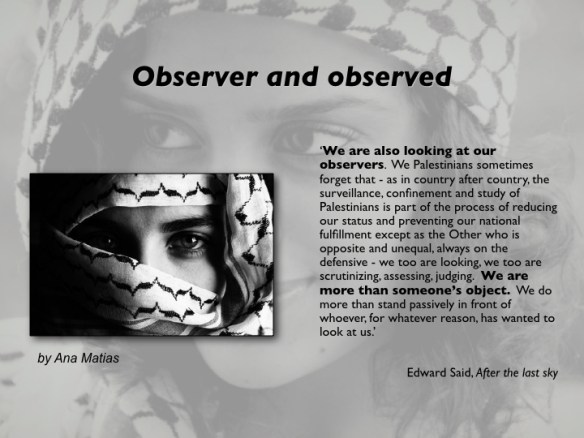

It’s part of a special issue on ‘Visual Revolutions in the Middle East’, and as I explore the visual interventions I’ve included in this post I find myself once again thinking of a vital remark by Edward Said:

That’s part of the message behind the #NotaBugSplat image on the cover of Steve’s essay: but what might Said’s remark mean more generally today, faced with the proliferation of these seeing machines?