This is both an interruption of and a supplement to my series of essays on the siege of Ghouta in Syria (‘Mass Murder in Slow Motion’): you can find the first (‘East Ghouta’) and second (‘Siege Economies’) here and here, and there are two more to come. My focus here – and hence my title (in sixteenth-century Europe a masque was a theatrical entertainment staged to glorify the royal court) – is on two performances staged after the mass casualty attacks on Douma on 7 April 2018: the first by the United States, France and the United Kingdom when they launched air strikes on 14 April against three sites that they claimed were central to Syria’s chemical weapons programme, and the second by Syria, Russia and their proxies on the right and the left who insisted that the reports of the original attack were ‘chemical fabrications’. Both performances, I suggest, are deeply suspect.

I begin by setting the scene – the immediate preconditions to the attack – and then draw on testimony from witnesses on the ground to document what happened in Douma on the evening of 7 April. I then consider each performance in detail: the process through which the US and its allies decided that, on the balance of probabilities, the Assad regime had used chemical weapons in Douma, determined their military response, and justified their actions; and the mobilisation of what Bethania Palma called ‘disinformation machines’ by Syria, Russia and its proxies to proclaim ‘fake news’ and erect ‘false flags’.

Under the bombs

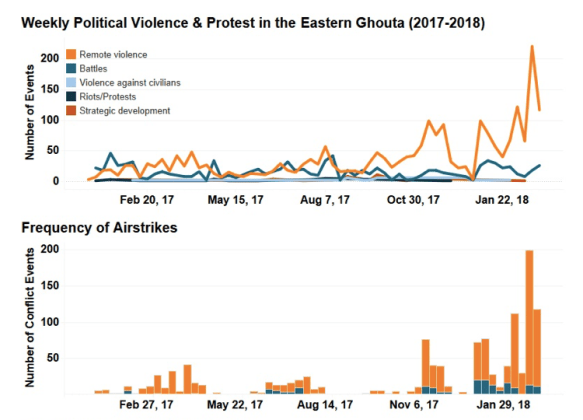

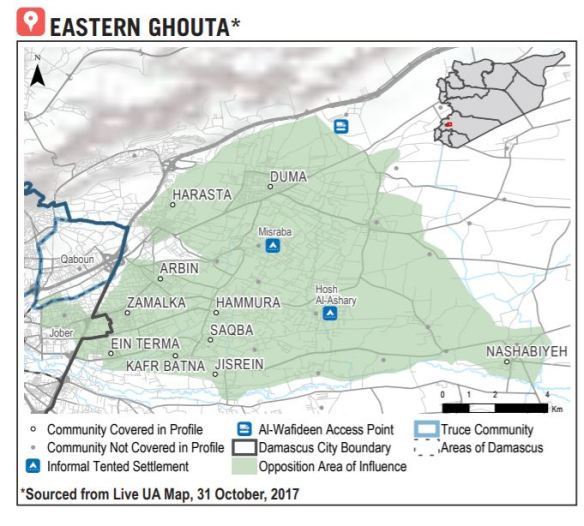

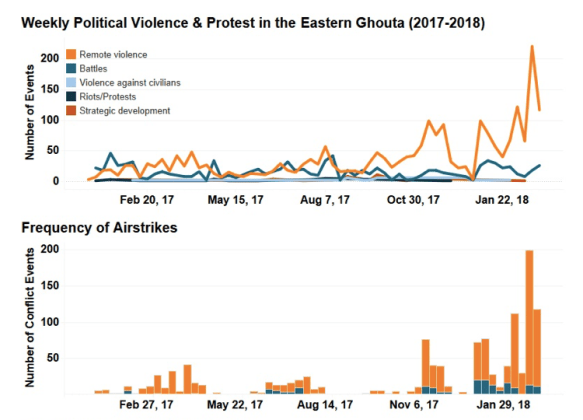

The joint military offensive against East Ghouta proved to be an extraordinarily violent campaign. Over the summer of 2017 the Ghouta had been designated a ‘de-escalation zone‘, but attacks by the Syrian Arab Army and its allies and proxies resumed during the autumn and intensified spectacularly from January 2018. Here’s a snapshot summary from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED):

The siege was now absolute; hospitals were repeatedly bombed, and hundreds of civilians killed during a devastating onslaught of bombs, shells and missiles. ‘It’s not a war, it’s called a massacre’, one doctor told the Guardian in February 2018:

“The bombing was hysterical,” said Ahmed al-Dbis, a security official at the Union of Medical and Relief Organisations (UOSSM), which runs dozens of hospitals in areas controlled by the opposition in Syria. “It is a humanitarian catastrophe in every sense of the word. The mass killing of people who do not have the most basic tenets of life.”

UNICEF issued a blank page as a statement to condemn the relentless assault – it had no words left to describe what was happening:

Sonia Khush, an official with Save the Children, described the situation as “absolutely abhorrent.” “The bombing has been relentless, and children are dying by the hour,” she said. “These families have nowhere left to run – they are boxed in and being pounded day and night.”

Many of them sought refuge in basements and improvised subterranean shelters. Here is a report on 21 February from Megan Specia and Hwaida Saad:

All of eastern Ghouta is underground. That is how one aid worker described the situation as thousands of people fled into basements and makeshift shelters in the rebel-held suburb of Damascus this week. Eastern Ghouta is under a brutal aerial assault by Syrian government forces that has left more than 200 people dead in recent days, including many children. As the war on the outskirts of the capital reached a new level of intensity, families huddle underground. For hours on end, they wait out the bombing, which shows no signs of slowing….

Many see the basements as the only haven in a hostile environment. They had little chance to evacuate, as the area has been blockaded for months. For Shadi Jad, a young father who has been in a basement since the beginning of the week, his shelter is a mixed blessing. “Honestly, I feel the shelter is a grave, but it’s the only available way for protection,” he said when reached on Tuesday. But Mr. Jad, who is hiding with his wife and eight other families, said that being in close quarters had also drawn his community together. “We share stories, try to keep the fear away by telling some jokes,” he said. “The shelter makes the relationships deeper”…

Hoda Khayti, 29, has lived in eastern Ghouta her whole life, and said her family, like most of their neighbors, had spent much of the week in a basement. Twelve other families joined them in one cramped space. They could hear planes constantly passing overhead. “The scariest moments are when rockets land, then silence follows,” Ms. Khayti said when reached Wednesday on a Facebook video call. “We feel our souls are leaving our bodies when the plane gets close, and we feel relieved after it goes away.” They fear the bombs outside, but like Mr. Jad, Ms. Khayti said the shelter has become a place for the community to come together. They share food, blankets and stories while they wait for the sounds of planes overhead to trail off….

Conditions rapidly deteriorated; the basements and shelters were hopelessly overcrowded, most with no heating or electricity, sanitation or running water. Listen to Neemat Mohsen in Saqba in early March:

“In our street, over 500 metres there are only three basements. They have to house all the families there. We feel the prison shrinking. We were first besieged in an enormous prison called eastern Ghouta, now we are trapped in shelters similar to tombs… We are living real terror 24 hours a day.”

By the middle of March the offensive had succeeded in dividing the enclave into three:

Russia brokered a series of evacuation deals and prisoner exchanges with the major rebel groups, first with Ahrar al-Sharm who agreed on 21 March that its fighters, their families and others would leave Harasta, and then with Faylaq ar-Rahman who agreed on 23 March to leave Ayn Tarma, Irbin, Jobar and Zamalka. Over the following days convoys of buses left for Idlib, while thousands of people fled on foot through so-called ‘humanitarian corridors’ to government camps on the outskirts of Damascus; still others elected to stay in their shattered neighbourhoods under the terms of a security deal to be enforced in the first instance by Russian military police.

That left Douma, where an uneasy truce lasted for ten days – broken by intermittent air strikes – while Jaish al-Islam (JAI) negotiated terms. These were complicated by divisions within JAI. Some of its members wanted to fight on, while others wanted to leave with their families but refused to go to Idlib – not only was the rebel-held area widely regarded as an elaborately constructed kill-box where the Syrian Arab Army would soon resume its offensive, but JAI had a ‘blood feud’ with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham which controlled much of the area.

Negotiations stalled and eventually broke down. JAI reportedly placed new conditions on evacuation and refused to release prisoners it had held captive for several years, and on the afternoon of Friday 6 April JAI shelled Damascus, killing four and wounding another 22. The assault by the Syrian Arab Army and its allies resumed with a vengeance. A ground offensive was launched under the cover of a sustained air and artillery bombardment broadcast live on state TV. There were 50 air raids during the afternoon and evening, and a medic inside one local hospital – desperately short of trained staff and supplies – described the chaos as the dead and wounded were brought in:

The hospital is in a state of panic… Dentists are carrying out emergency surgeries. Dead bodies are being brought in pieces and are unrecognisable.

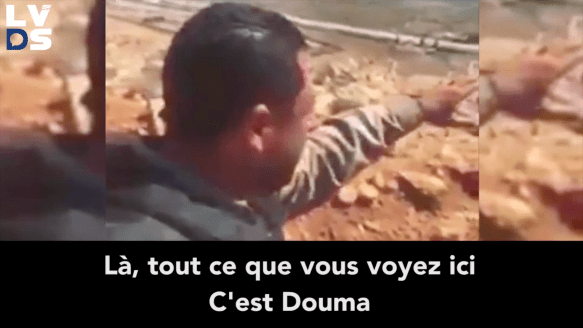

That afternoon Hosein Mortada (above), a reporter for Press TV and al-Alam and a vocal supporter of the Assad regime, released a video from Mount Qalamun where he was embedded with the artillery batteries that were pounding Douma, with columns of smoke towering into the sky behind him. His commentary:

These are appetizers… The story is bigger than a ground invasion. There is something they will see today if the story continues. They will feel something very strong.

It’s impossible to say whether Mortada knew what was coming – he certainly enjoyed close access to the Army – or whether he was merely continuing the gloating and goading style of ‘reporting’ that had become his signature. Or perhaps he was riffing on the terrifying warning issued in February by Brigadier-General Suheil al-Hassan, the officer commanding Syria’s elite Tiger Force which was now leading the assault on Douma:

I promise, I will teach them a lesson, in combat and in fire… You won’t find a rescuer. And if you do, you will be rescued with water like boiling oil. You’ll be rescued with blood.

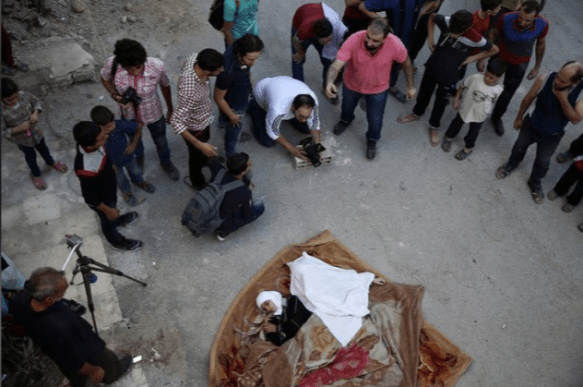

The air and ground assault intensified throughout the next day (above), and most people returned to or remained in the basements and shelters that had been their wretched homes for weeks that had dragged into months. Then, on Saturday night, there were suddenly multiple reports of mass casualties.

‘Gas! Gas!’

In a preliminary analysis the Violations Documentation Centre zeroed in on three strikes on 7 April involved in what it described as a ‘suspected chemical attack’.

The first, at 1200, targeted a Syrian Arab Red Crescent medical centre with guided missiles and barrel bombs; the centre was virtually destroyed along with its complement of ambulances (hospitals have long been a target of the Russian and Syrian Arab Air Forces: see here). Although the strike had a paralysing effect on the medical response to later strikes, I’m not sure why it was included; an early report from the Syrian-American Medical Society claimed that a ‘chlorine bomb’ had hit a Douma hospital but no time was given, and a subsequent joint statement from SAMS and the Syrian Civil Defence (‘White Helmets’) addressed the situation later that evening:

On Saturday, April 7th, at 7:45 PM local time, amidst continuous bombardment of residential neighborhoods in the city of Douma, more than 500 cases – the majority of whom are women and children – were brought to local medical centers with symptoms indicative of exposure to a chemical agent. Patients have shown signs of respiratory distress, central cyanosis, excessive oral foaming, corneal burns, and the emission of chlorine-like odor.

During clinical examination, medical staff observed bradycardia, wheezing and coarse bronchial sounds. One of the injured was declared dead on arrival. Other patients were treated with humidified oxygen and bronchodilators, after which their condition improved. In several cases involving more severe exposure to the chemical agents, medical staff put patients on a ventilator, including four children. Six casualties were reported at the center, one of whom was a woman who had convulsions and pinpoint pupils.

The casualty figures were subsequently revised upwards, but those cited here seem to have been victims of the other two strikes on the list, which were unambiguously attributed to ‘chemical weapons’.

The second, at 1600, targeted the Saada Bakery on May Ibn al-Khattab (bakeries have long been a staple of Russian-Syrian air strikes too as part of the ‘starve or surrender’ strategy of siege warfare).

The third, at 1930, targeted an apartment building near al-Shuhada Square near al-Numan Mosque.

The many eyewitness accounts are not easy to reconcile with the map: the experience of an air strike fragments both experience and language, and at first it was difficult for rescuers to pinpoint the sites that had been attacked (one rescuer told the VDC: ‘At the start of the chemical attacks, the smell of chlorine reached the center of the city of Douma. We could not determine the area where the chlorine rocket had fallen.)

Nevertheless a common narrative does emerged from multiple sources scattered across different locations inside Douma. Here are its main outlines.

A network of flight monitors – which warns people of impending attacks and which has also been used to identify the perpetrators of previous air strikes (see for example here) – tracked Syrian Mi-8 helicopters flying southwest from the Dumayr airbase towards Douma. I’m not sure how significant this is, and I haven’t been able to obtain more details; the intensity of the strikes suggests multiple aircraft were involved. But Syrians opposed to the Assad regime have become hideously accustomed to barrel bombs dropped from Syrian Arab Army helicopters (see above: Arbin, 20 February 2018), and one report claimed that the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Directorate was also intimately involved in targeting East Ghouta with chlorine gas dropped from its helicopters. That night several people in Douma reported hearing the whirring of helicopter blades overhead followed by the sound of objects falling from the sky. There were also witnesses who saw the projectiles descend; they described a ‘green gas emanating from the canisters falling from the sky’ and rushed down to the basements to warn those huddled in the shelters below to evacuate immediately.

As I read these accounts, I remember the words of Hoda Khayti that ended the report from Ghouta I cited above: ‘I don’t want to die in the basement.’ One rescuer underlined the urgency of escape:

There were basements in other buildings with people who didn’t see the gas in time. We entered those buildings and found bodies on the staircases and on the floor – they died while attempting to exit.

He made repeated forays to help people out:

By his third frantic dash down the stairs, with a wet piece of cloth over his mouth and a little girl in each arm, everything went dark for Khaled Abu Jaafar. “I lost consciousness. I couldn’t breathe any more; it was like my lungs were shutting down…”

Quick actions like these saved many people’s lives, but their escape was fraught with danger.

“Someone yelled chemical” Umm Nour recalls. “I felt my throat close, my body go limp as if I had just had everything sucked out of me.” She reenacts how her arms tensed up, how she could barely muster the strength to grab her daughters’ arms and claw her way up the stairs. They made it to the fourth floor when artillery rounds or rockets – she’s not sure what – slammed into the building, shaking it. “It was like we were between two deaths,” she says. “The chemical attack on the lower floors or the other strikes hitting the upper ones.”

But for some people in locations closer to the deadly canisters this proved to be the wrong choice:

Another canister landed on a bed on the upper floor of a damaged building and did not explode, according to a video shot by an activist who found it. A third canister was found on the roof of a crowded, four-storey apartment building near the city center, according to a video of the canister and an activist who visited the building the next day. Rescue workers … found dozens of men, women and children lying lifeless on the floor below… It appeared that when the smell entered the basement, some people had tried to go upstairs to get fresh air, unknowingly getting closer to the source.

Cellphone videos of the canisters and the aftermath of the attack on the apartment building near al-Shuhada square were uploaded to social media platforms, and you can find a preliminary but none the less detailed analysis of them – including geo-location (below) – from Eliot Higgins and his team at Bellingcat here.

For those working in makeshift clinics the scenes were no less horrifying:

“We were 12 people, and before the attack you can imagine, we had been working perhaps 30 hours or more without stopping,” said one paramedic who treated the victims. “Then you start getting a lot of people who are suffocating, and they smell of chlorine, and imagine after all that exhaustion you get this huge number of people, around 70, targeted while they were in bomb shelters.” He added: “We gave them whatever we had, which wasn’t much, just four oxygen generators and atropine ampoules so they could breathe … Most of them were going to die. You can imagine now our psychological state. It’s tragic. I’ve been working in this hospital for five years and those last two days, I haven’t seen anything like it.”

A local reporter described what he saw at one field hospital as apocalyptic:

I went to a medical point that is an underground hospital, and in the tunnels the dust was filling the area and there were women, children and men in the tunnels. When I arrived at the medical point it was like judgment day, people walking around in a daze, not knowing what to do, women weeping, everyone covering themselves with blankets, and the nurses running from victim to victim. There were entire families on the floor covered in blankets, and there were around 40 dead in shrouds lying between the families, their smell filling the place. The situation, the fear and the destruction are indescribable.

These first accounts are saturated – in image and in word – with the sensations of an attack by chemical weapons (CW). The people of Ghouta, and of rebel-held areas in Syria more generally, are no strangers to such attacks: they know their smells, their signs and their symptoms.

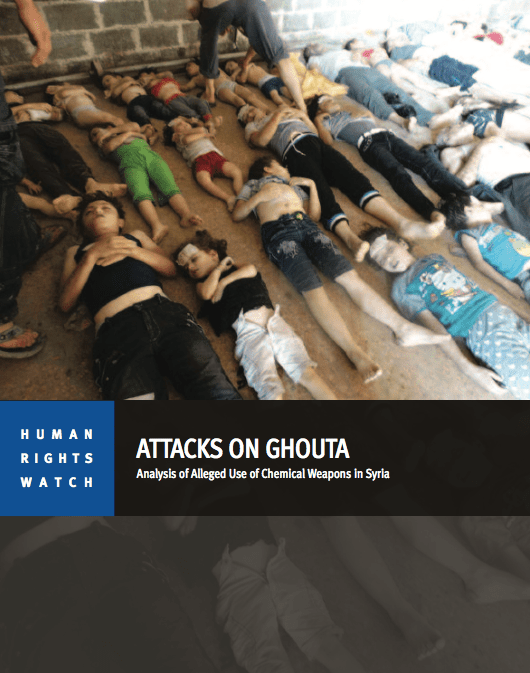

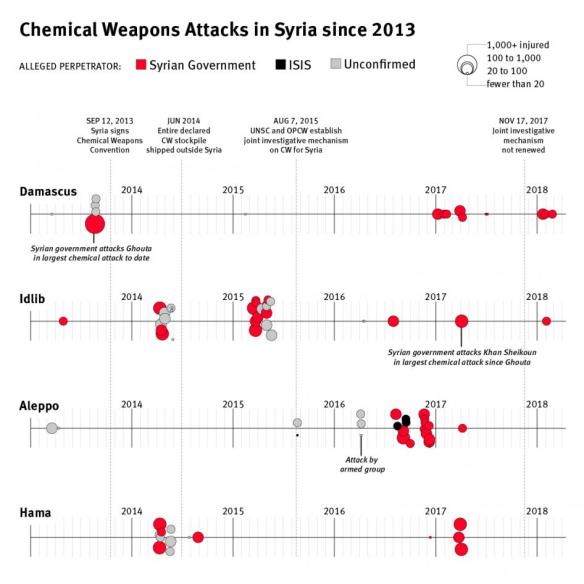

In fact on 4 April, just three days earlier, Human Rights Watch had followed up its previous forensic investigations of the use of chemical weapons against rebel-held neighbourhoods in West Ghouta and East Ghouta on 21 August 2013 – Attacks on Ghouta (2013; above) – and the ‘widespread and systematic’ use of CW by the Assad regime – Death by Chemicals (2017) – with an inventory of 85 confirmed CW attacks between 21 August 2013 and 25 February 2018:

HRW concluded:

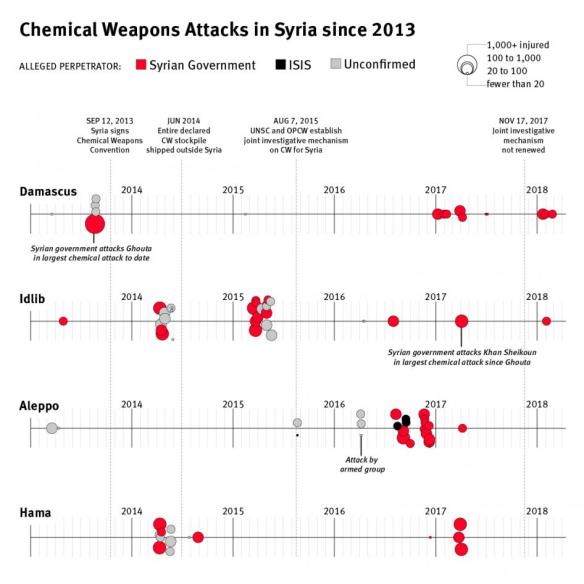

Of the 85 chemical weapon attacks analyzed … more than 50 were identified by the various sources as having been committed by Syrian government forces. Of these, 42 were documented to have used chlorine, while two used sarin. In seven of the attacks, the type of chemicals was unspecified.

The … Islamic State group (also known as ISIS) carried out three chemical weapon attacks using sulfur mustard. One attack was by non-state armed groups using chlorine. Those responsible for the remaining attacks in the data set are unknown or unconfirmed.

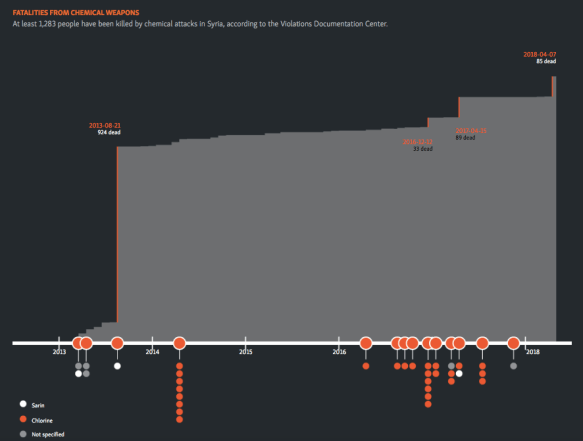

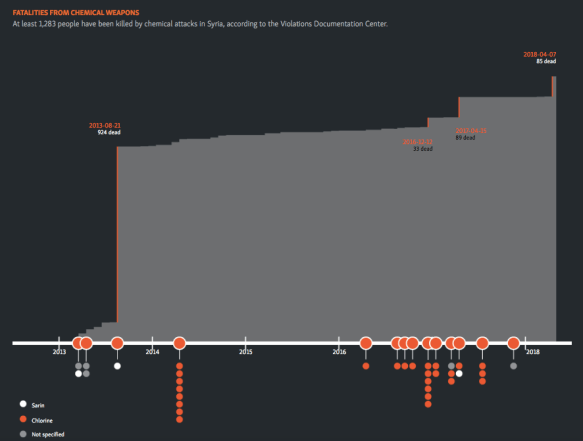

This graphic, based on the work of the Violations Documentation Centre, charts the cumulative number of deaths from suspected CW attacks in Syria:

Some of these previous investigations had attracted fierce controversy and criticism, but even so it’s difficult to make a credible case that those who observed the aftermath of the air strikes on 7 April 2018 would not have known what they were talking about.

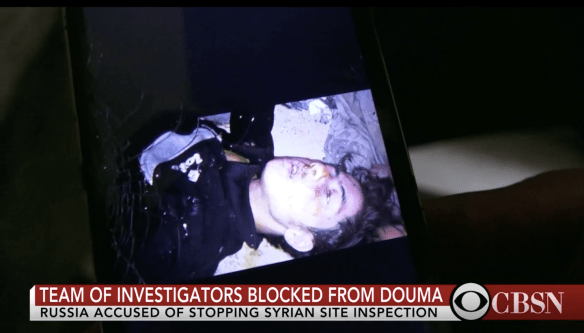

Their immediate impressions were supported by remote experts who subsequently examined the reports and the videos. Most concluded that the symptoms of the victims of the strike on the Saada Bakery and its vicinity were consistent with a chlorine gas attack, but the casualties from the strike on the apartment building exhibited even more troubling symptoms that suggested chlorine had been used in concert with a nerve agent like sarin.

Dr Raphael Pitti, a former military doctor and now professor of Emergency Medicine in War Zones at Nancy and a Board Member of UOSSM-France asked to be supplied with digital photographs and metadata to establish their provenance (date, time sequence and location), together with close-up images and video of the victims’ eyes. The casualties from the Saada area had trouble breathing, irritated eyes and other symptoms consistent with chlorine poisoning, he said, but those who died in the apartment building seemed to have been struck down with a speed that was totally inconsistent with even a high-concentration chlorine attack, and they exhibited convulsions and other symptoms usually associated with sarin or a similar nerve agent. In his view, it was likely that chlorine had been used in that attack too – but to mask the presence of another toxin.

Similarly, Dr Alastair Hay, professor of toxicology at Leeds, speaking to the Washington Post on 10 April after watching the videos on line:

“It’s just bodies piled up. That is so horrific… There’s a young child with foam at the nose and a boy with foam on its mouth. That’s much, much more consistent with a nerve-agent-type exposure than chlorine…. Chlorine victims usually manage to get out to somewhere they can get treatment… Nerve agent kills pretty instantly.”

Or again, from Martin Chulov‘s report in the Guardian on 12 April:

Jerry Smith, who led the [OPCW-UN] mission to supervise the withdrawal of the Syrian government’s stockpile of sarin in late 2013, said the symptoms displayed by patients could suggest exposure to an agent in addition to chlorine. “It’s worth elucidating the knowns,” he said. “Casualty rates, apparent speed of death and the shaking.” Organophosphate-based poison, including sarin, causes such symptoms. Pinpoint pupils and severe mouth foaming have been telltale signs in past attacks.

A guilty verdict

These were the stocks of knowledge in the public domain that most commentators and analysts in North America and Europe drew upon in the aftermath of the attacks on 7 April. The evidence, to many, was compelling – the Assad regime’s (criminal) record of CW use, first-hand testimonies and videos, and the submissions of expert witnesses – but it was still not conclusive.

Raphael Pitti emphasised that the only way to establish definitively what agents had been used was through laboratory examination, which was one of the central task’s of the investigation team from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). In an interview with France 24 Olivier Lepick, a researcher from the Fondation pour la recherche stratégique in Paris, explained:

“The inspectors will be able to do two things on the ground: they can get physiochemical samples from places affected by the attack – on the walls, on the ground – and they can take biological samples from victims, either wounded or dead, to look for metabolic evidence of a chemical agent in their fluids [urine and blood in particular].”

But time was of the essence; blood and urine samples will only show traces of chemical contamination for a week or so at most.

“Every day that passes makes the results of any investigation less clear, and in this case the relevant area is controlled by the main suspects, who will be tempted to cover up the evidence,” Lepick continued. The researcher said that “bleach-style” cleaning is enough to remove traces of toxic agents on the spot, while the evidence in biological samples from victims becomes increasingly hypothetical with time and can be removed by the Syrian army. That is why the OPCW’s policy is to send teams 24 to 48 hours after the incident.

The arrival of the OPCW team in Douma was repeatedly delayed; the reasons ranged from maladministration (the nine team members supposedly did not have the necessary clearances from the UN, an excuse flatly denied by the UN) to security concerns. The Russian and Syrian authorities who controlled access to the city did not permit the investigators to begin their ground inspection until 21 April, when they successfully obtained samples from one site which were sent to the OPCW laboratory at Rijswik in the Netherlands for onward transmission to designated independent labs for analysis (for details see here). There were fears that in the two weeks since the alleged attacks took place any chemical residues (especially chlorine) would have degraded, and allegations were also made that the sites had been compromised or sanitised – though at least one expert maintained that it would be extremely difficult to remove the signs of removal! – and that potential witnesses had been intimidated and coerced.

In anticipation of these obstacles efforts had already been made to fast-track the process of verification outside the OPCW. Here is Martin Chulov again on 12 April:

In Jordan, officials prepared to receive biological samples from some of the estimated 42 dead and the hundreds more who survived. Smuggling routes in and out of Damascus are well travelled, and makeshift crossings along the watertight Jordanian border can suddenly open whenever there’s a need. Getting samples, especially corpses, to laboratories has been a top priority this week as the US has tried to establish if the gas that was dropped contained more than chlorine.

Other reports claimed that activists had smuggled blood, urine and hair samples across Syria’s northern border into Turkey for analysis.

The route followed by the samples remains unknown, but in short order US officials announced the results of tests on blood and urine samples from victims of the Douma attacks: they had tested positive for chlorine gas and for a sarin-like nerve agent. No details of the chain of custody – or of the testing process – were released, but even if they had been established, as Raphael Pitti also emphasised, the problem of assigning culpability would remain. That used to be the task of the Joint Investigative Mechanism between the OPCW and the UN whose mandate had been terminated by a Russian veto in November 2017.

The United States – or at least its improbable, impossible president – had never entertained any doubt about culpability: the Assad regime was again guilty of a chemical weapons attack. One week after the attacks on Douma, a course of (military) action had been agreed between the US, France and the United Kingdom.

The timing was perplexing. Many critics argued that it was a rush to judgement; that all the relevant evidence had not been gathered and that there remained reasonable (to some, even considerable) doubt about what had happened and who was responsible. But others were surprised at what they saw as a stay of execution: a year earlier the US had decided on its military response to the chemical weapons attack on Khan Shikhoun within 48 hours. On the first count, there were questions about whether any further, untainted evidence would be forthcoming; and it is also significant that Trump, Macron and May were all beset by domestic political crises for which international action was almost always a useful distraction. On the second count, this was a multi-national mission that required consent and co-ordination, and all three states had serious concerns about escalating what was being described as a new Cold War with Russia.

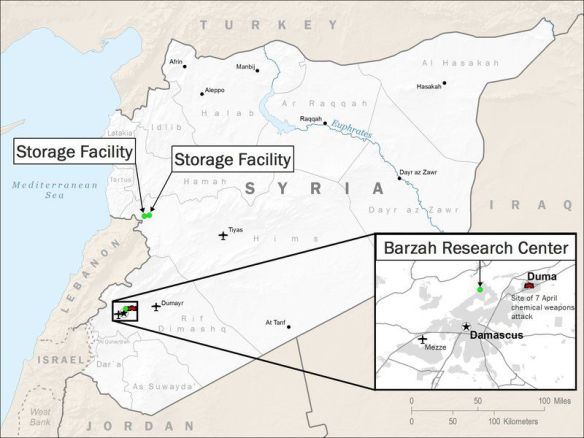

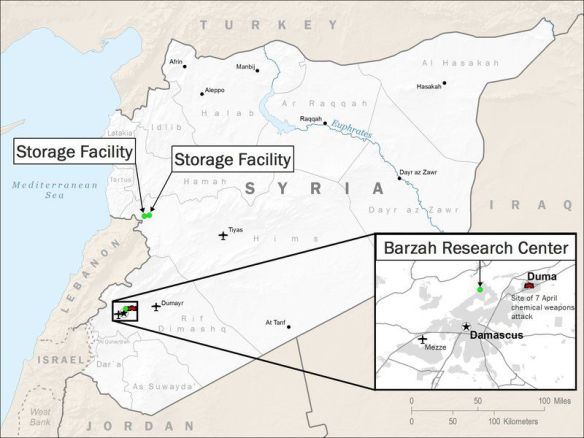

The three allies launched co-ordinated ‘precision’ strikes before dawn on 14 April against three targets. The closest to Douma was the Barzah Research and Development Centre, NE of Damascus, described by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as a military facility ‘for the research, development, production and testing of chemical and biological warfare technology’. The other two sites were west of Homs: the Him Shinshar Weapons Storage Site, ‘the primary location of Syrian sarin and precursor production equipment’, and 7 km away the Him Shinshar Chemical Weapons Bunker, ‘both a chemical weapons equipment storage facility and an important command post.’ The Pentagon issued this map of the three targets:

The primary roles were played by the US and France. Cruise missiles were launched from US warships and submarines in the Gulf and the Red Sea and from French warships in the Mediterranean, while US, French and British aircraft also launched missiles against the three sites: the central target was Barzah, followed by the Him Shinshar Weapons Storage Site. The origins and distribution of the ordnance used is captured in these two graphics:

The joint response raises a series of important questions about the effectiveness of the strikes; the humanitarian claims that were registered to legitimise them in the court of public opinion; and their propriety under international and domestic law. I’ll consider each in turn.

The interval between the attack on Douma and the strikes on the three sites was used not only to assess culpability but also to develop the target set. The last time the US had conducted a strike in response to a CW attack in Syria was on 7 April 2017 when Tomahawk cruise missiles were fired from destroyers in the eastern Mediterranean against Al Shayrat airbase where the attack had originated. At least six major airbases have been linked to Syria’s chemical weapons programme – including Dumayr from which the helicopters were tracked towards Douma – but none of them was on the list this time around. This is not surprising. The previous counter-strike had had precious little effect; the base was back in operation within 48 hours and the gesture had no discernible deterrent function. There were also concerns about the proximity of many of the bases to Russian forces – Moscow had issued a series of bleak warnings about the dangers of ‘provocation’, and there have been reports that the Russian military was consulted over its ‘red lines’ which were not violated by the targets selected. Major CW factories were also removed from the list, like the Scientific Studies Research Centre at Jamraya, just north of Damascus, which had been attacked by Israeli jets in February; ‘Factory 790’ at al Safira in Aleppo province (Syria’s largest weapons manufacturing plant and suspected to be a major source of sarin), and the Masyaf research and development centre in Homs province (another suspected location for sarin production, also previously attacked by Israeli jets).

According to the Washington Post,

While officials had been watching known Syrian chemical sites on and off for years, aerial surveillance time has been dedicated mostly to other areas of Syria, where the United States and allied local forces continue to battle the Islamic State. That meant the U.S. military needed to refresh its intelligence on the chemical facilities before targeteers could build the “target packages” that would guide the operation.

The delay was the product of more than intelligence gaps; concerns about the possibility of killing civilians were also said to be paramount, and at a Pentagon briefing Lt General Kenneth McKenzie conceded that while ‘we could have gone to other places and done other things’ the three selected targets ‘presented the best opportunity to minimize collateral damage’. But these claims sit uneasily with the US-led coalition’s record of air strikes in Syria more generally. Casualty estimates are fraught with difficulty, but Airwars estimates that between August 2014 and April 2018 a minimum of 6,259 to 9,604 civilians have been killed by coalition air strikes in Syria and Iraq; the breakdown of civilian casualties for Syria is shown graphically below (see also Craig Jones here):

McKenzie claimed that the strikes ‘significantly degraded’ Syria’s ability to use chemical weapons in the future and that Barzah – which ‘does not exist anymore’ – had been ‘the heart of the Syrian chemical weapons program’. Yet this remains an untested assertion. In elaborating on the Pentagon’s collateral damage estimation, McKenzie referred to ‘a variety of sophisticated models – plume analysis, other things, to calculate the possible effects of chemical or nerve agent [dispersion]’ after an attack. But it’s possible to turn this round. The very next morning Rim Haddad described the scene at Barzah for AFP; ‘plastic gloves and face masks lay scattered in the rubble’ and, hours after the strike, ‘plumes of smoke wafted lazily up from the building and a burning smell still hung in the air.’ This was clearly a report from the ground not one conducted over Skype, still less one that relied on satellite imagery. Said Said told Haddad that he worked at the site as an engineer and denied any involvement in the production of chemical weapons. You might find that unremarkable for various reasons, but Said then added this disturbing rider:

If there were chemical weapons, we would not be able to stand here. I’ve been here since 5:30 am in full health — I’m not coughing.

And he wasn’t alone; Syrian soldiers were inspecting the ruins too – as was the press crew.

In short, it’s not unreasonable to wonder, with David Sanger and Ben Hubbard at the New York Times, whether any of the three sites were still in use:

At this point, there are no known casualties at the sites, which suggests that either no one was there during the evening, or they had been previously abandoned. And there are no reports of chemical agent leakage from the sites, despite attacks by more than 100 sea- and air-launched missiles.

Yet perhaps this misses the point. For all Trump’s boasts about ‘Mission Accomplished’, the raids ‘so perfectly carried out, with such precision’, the effectiveness of the strikes rested on more than their destructive capacity. They were also supposed to be ‘constructive’, performative: to send an unambiguous message to Assad and his allies. But what exactly was the message?

The junior partner in the mission, British Prime Minister Theresa May, proclaimed that the joint military response was justified ‘because we cannot allow the erosion of the international norm that prevents the use of these [chemical] weapons.’ It’s more than an international norm, of course: it’s also a matter of international law. But what about the other international laws so routinely violated by the Assad regime and its allies? The prohibition against torture (though I concede that the United States, France and the United Kingdom all have exceedingly dirty laundry hidden in that particular closet)? The collective punishment of civilian populations through the siege tactic of ‘surrender or starve’ (see here and here)? The prohibition against attacking hospitals and denying medical care to the sick and the wounded in war zones (see here)?

Moustafa Bayoumi sharpens the point with magnificent anger (and ‘perfect precision’):

The fact that three of the world’s most powerful militaries have now been mobilized into action, even for a limited campaign such as this one, to prevent “the erosion of the international norm” of using chemical weapons is far from comforting. Since the war began, Assad’s regime has engaged in the repeated and dreadful use of barrel bombs and mass starvation, the systematic torture of thousands of citizens and the laying siege to multiple cities, the killing of hundreds of thousands of people and the displacement of more than half the population. Yet, all of this horror does not seem to “erode an international norm” and certainly has not motivated these western leaders to any meaningful action to end the war… Rather than limiting war, this latest bombing of Syria normalizes the war’s ongoing brutality.

Or, as Robin Wright reported in the New Yorker:

“So you strike. Then what?” Ryan Crocker, a former Ambassador to Syria (as well as Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Kuwait), told me. “If the rockets hit the targets they intended, you could say the mission was accomplished in a narrow sense. But, in reality, it accomplished nothing. It might have been better if we’d not struck at all. It’s sending a message that killing is O.K. any way but one way — with chemical weapons. How many have been killed in Eastern Ghouta during this whole Syrian campaign? Far more by non-chemical means. It’s obscene.”

In short, the military response did more than draw a ‘red line’ against the use of chemical weapons (if it even did that): it gave a green light to virtually any and every other form of killing.

The legal map on which the missile strikes were located was – like all maps – shot through with circuits of power (and for what follows I am indebted to Jonathan Horowitz‘s succinct cartography here and here). The legal ‘ground truth’ for the start of the US-led bombing missions in Syria in September 2014 was a request from Iraq for the United States to conduct air strikes against the Islamic State. Some of those sites – not only paramilitary bases but also oilfields used by IS as sources of revenue – were located across the border in Syria, and the claim for cross-border intervention was reinforced by appeals under Article 51 of the UN Charter to ‘self-defence’ of allied forces inside Iraq and of their populations outside the region threatened by terrorist attacks from Islamic State. This joint effort was buttressed by a UN Security Council Resolution in November 2015 describing IS as ‘a global and unprecedented threat to international peace and security’ and calling on states to take ‘all necessary measures’ against IS, Al-Qaida and allied groups. These co-ordinates explain the pattern of civilian casualties displayed on the map above: these were primarily the result of strikes in IS-held territory. Some of the states involved also cited Syria’s ‘inability’ to prevent IS attacks as a further legal predicate. Although this clearly did not imply any invitation from Syria to intervene, it certainly suited the Assad regime to have other militaries pursue IS while its own forces fought rebel groups in other regions of Syria.

But these arguments cannot be extended to air strikes in response to chemical weapons attacks (unless presumably they were carried out by IS; it has been blamed for at least three previous attacks, but nobody has suggested it was responsible for the attack on Douma).

The case for the strikes as a humanitarian intervention failed to convince most jurists: of the three states involved, only the UK invoked humanitarianism as a legal justification. In 2015 Arabella Lang provided the House of Commons with a briefing on the legal case for UK intervention in Syria. The relevant discussion of humanitarian intervention reads as follows:

The UN Security Council can authorise military intervention for humanitarian purposes provided that it has determined that situation is a threat to international peace and security. But can states intervene in other states to deal with extreme human distress, without Security Council authorisation?

Some unauthorised humanitarian interventions have subsequently been commended by the Council, or at least condoned. But their legal basis remains controversial. There is also an argument that Article 2(4) of the UN Charter allows force to be used as long as it is consistent with the purposes of the UN (which include the promotion of human rights and the solving of humanitarian problems – Article 1(3)). Others suggest that even if humanitarian intervention without Security Council authorisation is unlawful under international law, it can still be legitimate – for instance the NATO intervention in Kosovo in 1999.

Some unauthorised humanitarian interventions have subsequently been commended by the Council, or at least condoned. But their legal basis remains controversial. There is also an argument that Article 2(4) of the UN Charter allows force to be used as long as it is consistent with the purposes of the UN (which include the promotion of human rights and the solving of humanitarian problems – Article 1(3)). Others suggest that even if humanitarian intervention without Security Council authorisation is unlawful under international law, it can still be legitimate – for instance the NATO intervention in Kosovo in 1999.

The ‘responsibility to protect’, as embodied in the 2005 World Summit Outcome (which is not legally binding), allows collective action against genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, where the state concerned has been unable to protect its citizens. However, the World Summit Outcome states that this must be done through the Security Council, so is not in that respect a development of the law on the use of force.

The UK is keen to develop the international law on humanitarian intervention. When putting the case for military intervention in Syria in 2013, it argued that intervention without authorisation from the UN Security Council is permitted under international law if three conditions are met:

• strong evidence of extreme and large-scale humanitarian distress;

• no practicable alternative to the use of force; and

• the proposed use of force is necessary, proportionate, and the minimum necessary.

Building on these arguments, the British government released its legal case on 14 April 2018. A military response to the alleged chemical attacks in Douma was ‘an exceptional measure’ but it was lawful ‘on grounds of overwhelming humanitarian necessity’:

- The ‘repeated lethal use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime constitutes a war crime’ and it was ‘highly likely the regime would seek to use’ such weapons again

- Other attempts to ‘alleviate the humanitarian suffering caused by the use of chemical weapons’ had been blocked and there was ‘no practicable alternative’ to the strikes

- The action was ‘carefully considered’ and the ‘minimum judged necessary for that purpose.’

Many legal scholars in the UK and elsewhere in Europe were unconvinced. A legal opinion prepared for the opposition Labour Party by Professor Dipo Akande of Oxford University’s Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict insisted that the government had to comply with international law as it was and not as they wished it to be (notice that reference in the earlier briefing to the government’s desire to ‘develop’ international law):

International law does not permit individual states to use force on the territory of other states in order to pursue humanitarian ends determined by those states.

A legal analysis conducted by the Bundestag’s research service reached substantially the same conclusion, and on the other side of the Atlantic even a passionate defender of humanitarian intervention like Harold Hongju Koh was not satisfied that the bar had been met (see also also Anders Henrikesen here).

These contrary opinions reinforced the central legal objection raised by most critics: that the US and its allies had responded to an alleged violation of international law by breaking it themselves. Jack Goldsmith and Oona Hathaway explain this with concision and clarity. The problem with claiming that Syria had breached the Chemical Weapons Convention (1997) – the central legal instrument in the case – is that the Convention ‘provides an enforcement system that the three powers involved in [the] airstrikes entirely bypassed’:

The Convention provides, first, for investigation by the experts from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons….

Then, in situations of “particular gravity,” the Conference of the States Parties may bring a matter to the attention of the U.N. General Assembly and Security Council. Nowhere does the Convention provide for unilateral uses of force in response to a breach of the Convention.

This is the formal, legal version of the ‘rush to judgement’ objection (above), and it has considerable force.

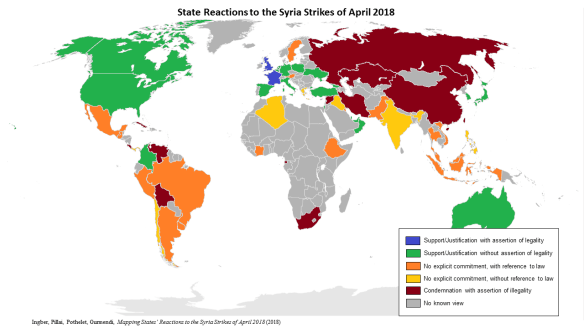

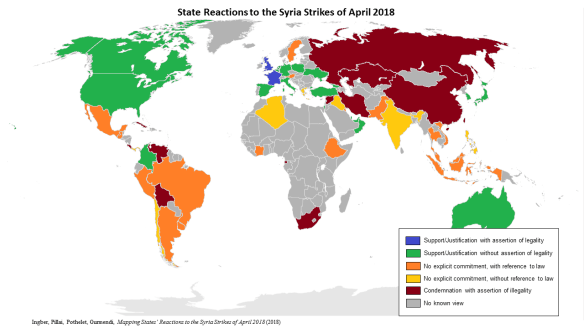

And yet the legal envelope governing military violence has often been extended through military violence (as Eyal Weizman puts it, ‘in modern war, violence legislates’), and Jan Lemnitzer has suggested that by virtue (sic) of these missile strikes – and the legal armature that yokes the humanitarian protection of civilians to the prohibition on the use of chemical weapons – we may be witnessing ‘the emergence of a new norm (customary international law) that justifies the use of force to counter the deployment of chemical weapons against civilians’ (for a more detailed discussion see Michael Schmitt and Chris Ford commenting on the 6 April 2017 missile strikes here). If this is the case – or if the UK’s wish to ‘develop’ international law on humanitarian intervention is in the process of being fulfilled – then this map of international state reaction to the strikes will be extremely important:

‘Fake news’ and ‘false flags’

Before and after the attacks on Douma, officials in Russia and Syria together with their proxies have been busily running all sorts of interference. These activities spin far beyond the the circles of presidents, ministers, ambassadors and their direct agents and even beyond the grey zone of disinformation sites and bot farms; there is also an army of one-trick academics, self-styled journalists and commentators populating a metastasizing archipelago of misinformation that reaches from the alt.right round to the alt.left. To set out my case in these non-neutral terms is not to endorse the statements and actions of the US, the UK and their allies. But objecting to the air wars conducted by this alliance does not mean suspending critical judgement about the actions of their opponents either. In the particular case of Syria, it means not turning a blind eye to the authoritarian constitution of the Assad regime and to the extraordinary, criminal violence it has visited on hundreds of thousands of innocent Syrians. As Mehdi Hasan asks, in another appropriately angry commentary I urge you to read, even if you doubt in all conscience that the Assad regime did launch a chemical weapons attack on Douma on 7 April, why minimize its other crimes and abuses? More here and here.

Those who have sought to defend the Assad regime against the charge of using chemical weapons in Douma have followed two main avenues.

A first response has been simply to dismiss the reports as ‘chemical fabrications’ and ‘deceitful speculations’: to insist that there was no evidence of a chemical weapons attack. On 8 April, for example, Ben Hubbard reported:

The Russian Foreign Ministry dismissed the reports as fake. “The spread of bogus stories about the use of chlorine and other poisonous substances by government forces continues,” the ministry said in a statement. “The aim of such deceitful speculation, lacking any kind of grounding, is to shield terrorists,” it added, “and to attempt to justify possible external uses of force.”

As the videos and testimonies I cited earlier circulated, the outright denials were replaced by an altogether more sensational scenario. Russian and Syrian officials claimed that the attack had been staged by Jaish al-Islam in concert with the Syrian Civil Defence (‘White Helmets’) and, by implication, the Syrian-American Medical Society and other NGOs:

(Particular opprobrium seems to be visited on any NGO providing medical help to the sick and injured in rebel-held areas, even though this is explicitly sanctioned by international law; it has also been consistently withheld and obstructed by the Syrian government).

The indictment eventually swelled to include the United Kingdom (which had claimed Russia was responsible for the nerve-agent attack on the former British spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter in Salisbury on 4 March); Reuters reported on 13 April:

“We have… evidence that proves Britain was directly involved in organizing this provocation,” [Russian] Defense Ministry spokesman Igor Konashenkov said. Konashenkov said that Russia knew “for sure” that between April 3-6, the White Helmets – a group which helps civilians in opposition-held territory in Syria – were “under severe pressure specifically from London to produce as quickly as possible this pre-planned provocation.”

The ‘evidence’ was never produced – nor were the British Special Forces soldiers allegedly captured as part of the operation paraded before the cameras either.

Instead, the disinformation campaign relied on two manoeuvres. The first was a counter-argument in the form of a question: what advantage could the Assad regime conceivably hope to gain by using chemical weapons when its forces were on the brink of defeating JAI and bringing all of East Ghouta under their control? This is a familiar tactic. When questioned about the targeting of hospitals in rebel-held areas Assad disingenuously asked: ‘… the very simple question is: why do we attack hospitals and civilians?’ There are sound answers to that – see my account of ‘The Death of the Clinic‘ – and there are to this version too. Remember that in the closing stages of the Syrian-Russian offensive against Douma negotiations with JAI had collapsed. Now here is Juan Cole:

On Saturday [7 April], the Russian press reported that Army of Islam spokesmen boasted that the [Syrian Arab Army] special operations Panther Forces (Quwwat al-Nimr) [this is a special unit of Tiger Force: see here] that had been committed against Ghouta militias were taking high numbers of casualties from Army of Islam snipers as they tried to advance into Douma. The regime has suffered a military collapse over the past seven years, with most Sunni Arabs deserting or defecting. Alawi Shiite troops are for the most part loyal to the regime, but there may be only 35,000 or 50,000 of them left (the Syrian Arab Army had 300,000 troops in 2010).

The long and the short of it is that strongman Bashar al-Assad cannot afford to lose highly trained and highly valuable Panther Forces troops in large numbers.

Chemical weapons are used by desperate regimes that are either outnumbered by the enemy or are reluctant to take casualties in their militaries… It might be asked why the regime would take this chance, given that Trump bombed the Shuaryat Air Force base last year this time in response to regime use of chemical weaponry at Khan Shikhoun. The answer is that the regime is more worried about disaffection in the ranks of its Special Forces than it is about Trump.

An investigation by Christian Esch and others for Der Spiegel added other plausible motivations:

Why would the Syrian regime deploy chemical weapons when it is already on the verge of victory? One motive could have been the desire to speed up the withdrawal of the hated rebels from the city. Douma was the last enclave remaining under rebel control. Or was it revenge? The Army of Islam, the Islamist group which controlled Douma, was relatively strong and regularly fired shells at nearby Damascus.

The Islamists long held a trump card in their hand: They were thought to be holding several thousand regime loyalists prisoner. That, however, was an exaggeration with which the Syrian regime sought to mislead its followers, a glimmer of hope that many troops long believed to be dead might still be alive after all. When it became clear that a large number of the presumed prisoners were in fact dead, it came as a painful blow and the thirst for revenge was correspondingly high. The rebels, meanwhile, had lost their trump card.

None of this settles matters, I realise, so let me turn the question around: what possible advantage could JAI conceivably hope to gain by staging a fake chemical weapons attack? If its leaders believed they could provoke a rapid military intervention (by whom?) to snatch them from the jaws of defeat – the Islamic equivalent of a Hail Mary pass – then it was a supremely stupid miscalculation: the immediate consequence of the attack, within a matter of hours, was the capitulation of Jaish al-Islam.

The second manoeuvre involved in the attempted indictment of JAI and others opposed to the Assad regime has been to substitute alternative evidence to counter the prosecutorial force of the videos, first-hand observations and expert testimony I detailed earlier. I’ll discuss three exhibits.

First, JAI’s ‘chemical weapons factories’. As the envelope of occupation in East Ghouta was extended, Syrian Arab Army officers escorted international journalists to several sites which they claimed were artisanal weapons factories. Eliot Higgins and the Bellingcat team already showed that Jaish al-Islam was indeed capable of producing makeshift weapons, including improvised mortars, rockets, grenades and rifles. But chemical weapons? In March Syrian TV broadcast video of what it described as a chemical weapons laboratory-cum-manufactory-cum-warehouse at al Shifuniya filled with industrial equipment:

The discovery was amplified by RT and other Russian news media before the attack on Douma:

The narrative was resurrected by dependent journalist Vanessa Beeley the day after the Douma attack. She cited the discovery of a ‘chemical weapons laboratory’ in the Douma Farms area between al Shifuniyeh and Douma, and then recounted a ‘similar experience’ – on the day before the attack – during ‘a foreign media trip to the liberated sectors of Eastern Ghouta with the Syrian Arab Army’. At Irbin she was shown ‘a bomb making factory and a chemical weapons facility’, including ‘chemical ingredients and rockets’ and a barrel containing what looked like tar (a significant discovery since she was under the impression that the Douma attack involved napalm, which was, as she explained at length, ‘an American invention’):

An expert who was with us said it was a mix of oil, soap and other ingredients that are used to coat the missile to ensure the chemical package sticks to its target more effectively. This was a factory of death… where the terrorist factions had designed some of the most sadistic weaponry possible to be used against civilian targets.

Several days later Adam Rawnsley asked Cheryl Rofer – a chemist who used to work at Los Alamos National Laboratory – and Clyde Davies, a former research chemist, to examine the videos of the buildings at al Shifuniyeh. They both agreed that whatever the facility had been used for it was highly unlikely to have been the production of chorine gas or sarin. Here are the key paragraphs from Adam’s investigation into what he concluded was a ‘chemical weapons lie’:

Asked if the equipment in the videos of Al-Shifuniya could be used to produce chlorine gas, Cheryl Rofer … said “no.” Chlorine is typically produced with electrolysis cells using either large amounts of salt or hydrochloric acid as feedstock and lots of electricity to produce and recover the gas. “Chlorine is a gas at room temperature and pressure,” explains Clyde Davies… “Its ‘critical point,’ below which it can be liquefied, is about 144 C, but it needs high pressure to do this, which is why it is stored and shipped in gas cylinders. Just like the ones that were dropped on Douma.”

The process can be dangerous and requires special equipment, according to the UN Joint Investigative Mechanism. “In the light of its corrosive and toxic nature, expertise and specialized equipment are required for its safe handling. For example, to transfer chlorine from a 1 ton container to smaller containers, a specialized filling station is required.” And this facility isn’t anywhere near “the scale needed for the attacks that have been observed,” Rofer wrote in an email. “All of the equipment, except for the boilers, is at laboratory scale. But the more fundamental problem is that none of the equipment is what is needed to produce chlorine and compress it into the cylinders that Bellingcat has documented” in Douma.

Nor could the facility be used to produce nerve agents. “For sarin production, all of this would have to be much more contained than it is,” Rofer writes. The ramshackle construction in the facility would’ve put anyone nearby at high risk of exposure, which can cause harm at very low concentrations.

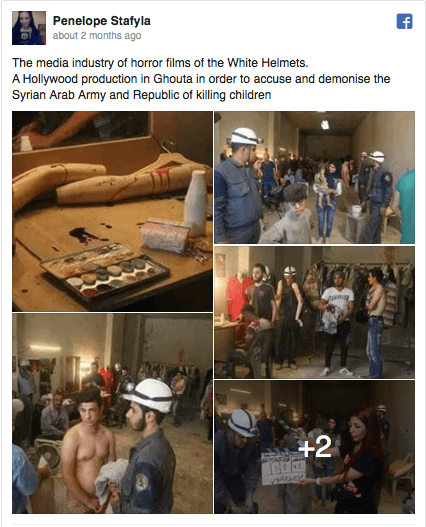

A second series of exhibits focused on the elaborate mise-en-scène of a staged chemical weapons attack. In order to discount the videos of the casualties in Douma – shot at multiple locations by different people – claims circulated that the video record (in its dispersed entirety) was faked. This too is a shop-worn tactic; the alt.right in the United States and elsewhere has consistently peddled a meretricious conspiracy fantasy of ‘crisis actors’ pretending to have survived supposedly non-existent incidents like the mass shootings at Sandy Hook or Parkland. Many of the same websites responsible for those repugnant claims have also stoked the fires of fantasy about Douma, like Alex Jones‘s ‘Infowars’ (see below, and the critical discussion by Bethania Palma and Scott Lucas here):

In the Douma case, however, photographs have been adduced as evidence for the artful staging of a chemical attack. Soon afterwards images showing actors being made up, covered in dust, and the cameras rolling were shown on Russian TV’s news programme Vesti, and they have circulated widely on the web. The first screenshot (‘The White Helmets unmasked by photographs’) is from the French-language site of globalresearch.ca and the second is from the source for the story, Pénélope Stafyla:

It was in this very studio, so these commentators claimed, that the Syrian Civil Defence – the White Helmets – fabricated ‘proof of war crimes committed by the Assad regime in East Ghouta’.

The photographs are not fakes; the performance was real. But an investigation by AFP’s fact-checking blog Factuel and Bellingcat discovered that these are all stills from a film, “Revolution Man“, which was shot in Damascus and funded by Assad’s own Ministry of Culture. Here is the film’s Facebook page:

And here is the film company’s synopsis of the project:

The film revolves around a journalist who enters Syria illegally in order to take pictures and videos of the war in Syria in search of fame and international prizes, and after failing to reach his goal, he resorts to helping the terrorists to fabricate an incident using chemical materials, with the aim of turning his photos into a global event.

In the Alice-in-Wonderland world of the fantasists, there was one more spin to the story: Vesti claimed that the film was shot by the White Helmets on a set standing in for the real set in which Revolution Man was shot… You can’t make it up — except, of course, you can. More here and here, and a discussion by Christian Chaise of AFP’s remarkable fact-checking protocols here.

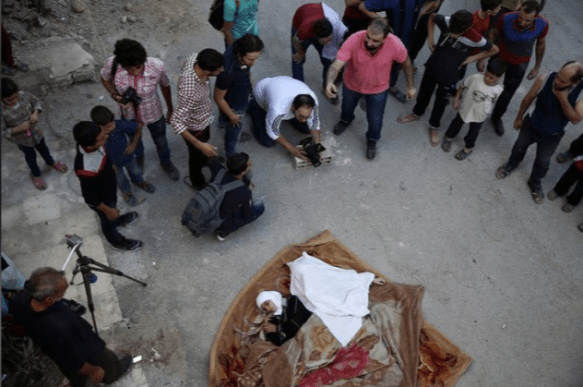

Another film, another fake. On 22 April Russia’s two main TV channels showed a series of still photographs from a film set as ‘obvious evidence’ that videos of the Douma attack had been staged and that the victims were were ‘crisis actors’. Faris Mohammed Mayasa, a production assistant who was by then in the custody of Syrian forces, confirmed that ‘We put people on the ground and sprayed them with water, so they looked as if they had suffered.’ Again, the photographs are genuine; they were taken on a film set; and, still more disturbing, the film was produced in the Ghouta (it was shot in Zamalka and edited in Douma):

But, as Marc Bennetts reported, the film was Humam Husari‘s Chemical, made in 2016 to tell the story of the sarin gas attack on the Ghouta in 2013. Husari had witnessed the effects of the attack himself – ‘I wasn’t filming because I am a cameraman, I was filming because this is the only thing I could do for the victims’ – and his short film was an attempt to explore how ordinary people had been drawn to the struggle against the Assad regime. Here is Lisa Barrington reporting for Reuters in October 2016:

Humam Husari’s self-financed short film explores the chemical attack near Damascus through the eyes of a rebel fighter who lost his wife and child but was denied time to bury them. Instead, he is called to defend his town from a government offensive. The story is based on real-life events, he said.

“We need to understand how people were pushed into this war and to be part of it,” said Husari, 30. “I am talking about a story that I lived with. They are real characters.”

Making the film was an emotional but necessary experience for Husari and his performers, who were witnesses to and victims of the attack, and not trained actors.

“The most difficult thing was the casting and auditions,” said Husari, who took about two months to write, produce and direct the 15-minute film and is currently editing it.

“A 70-year-old man said to me: I want to be part of this movie because I lost 13 of my family … I want the world to know what we’ve been through. And all I wanted from him is just to be a dead body,” he said.

The final series of exhibits has involved the substitution of other witnesses who vehemently deny that a chemical attack took place in Douma. Both Russia and Syria claim to have discovered witnesses whose testimony contradicts those I cited earlier. Most deny that any chemical weapons attack occurred, but a recent report by Robert Fisk for the Independent offers a particularly revealing example. While the OPCW team was prevented from starting its work in Douma by Syrian concerns about the security situation, the regime nevertheless arranged a tour of the shattered city for selected journalists. I should say at once that I have long admired Fisk’s reporting of Israel/Palestine; but this account is a sly, innuendo-ridden affair. Fisk says he wandered away from his minders:

It was a short walk to Dr Rahaibani. From the door of his subterranean clinic – “Point 200”, it is called, in the weird geology of this partly-underground city – is a corridor leading downhill where he showed me his lowly hospital and the few beds where a small girl was crying as nurses treated a cut above her eye. “I was with my family in the basement of my home three hundred metres from here on the night but all the doctors know what happened. There was a lot of shelling [by government forces] and aircraft were always over Douma at night – but on this night, there was wind and huge dust clouds began to come into the basements and cellars where people lived. People began to arrive here suffering from hypoxia, oxygen loss. Then someone at the door, a “White Helmet”, shouted “Gas!”, and a panic began. People started throwing water over each other. Yes, the video was filmed here, it is genuine, but what you see are people suffering from hypoxia – not gas poisoning.”

Ever since the combined bomber offensive of the Second World War we have known that many victims of air raids die of asphyxiation rather than blast injury, so suppose for a moment that Fisk’s doctor was not only sincere but also correct. In that case – since Jaish al-Islam has never had an air force – then dozens of civilians would have been killed and injured in a Russian or Syrian air raid. Yet Fisk doesn’t mention that; in fact he doesn’t dwell on the victims at all, who are rapidly airbrushed from the scene.

Instead the doctor’s testimony has been cited by commentators on social media to trump the claims of multiple other witnesses as singular ‘proof’ that no CW attack took place. Fisk doesn’t quite say that, and Jonathan Cook insists he doesn’t have to:

Fisk does not need to prove that his account is definitively true – just like a defendant in the dock does not need to prove their innocence. He has to show only that he reported accurately and honestly, and that the testimony he recounted was plausible and consistent with what he saw.

‘This is not the only story in Douma,’ Fisk concedes, before immediately adding:

There are the many people I talked to amid the ruins of the town who said they had “never believed in” gas stories – which were usually put about, they claimed, by the armed Islamist groups.

None of them is quoted, and apparently nobody else was available. ‘By bad luck, too, the doctors who were on duty that night on 7 April were all in Damascus giving evidence to a chemical weapons enquiry’: you could be forgiven for thinking that it was more than just the failure of the stars to align that prompted the Syrian and Russian authorities to arrange the press tour for the very day they also spirited the doctors away to Damascus. And while it was important to hear the White Helmets’ side of the story, Fisk continued, ‘a woman told us that every member of the White Helmets in Douma abandoned their main headquarters and chose to take the government-organised and Russian-protected buses to the rebel province of Idlib with the armed groups when the final truce was agreed.’ That is a remarkable sentence the more you chew on it: the bravery of the White Helmets in rescuing victims is ignored; instead they are artfully transformed into cowards running for cover at the first opportunity (‘abandoned their headquarters’); their fellow-travellers (sic) were the armed groups; and yet they were given sanctuary on ‘government-organised and Russian-protected buses’. Such generosity.

But that’s simply a drive-by smear. The main work is done by Fisk’s doctor, whose words are seemingly sufficient to rubbish or, if you prefer, cast doubt on all those other testimonies. He was not even was in the clinic when the casualties were brought in (‘I was with my family in the basement of my home three hundred metres from here on the night’, and Fisk himself admits that the doctors who were on duty that night were all in Damascus).

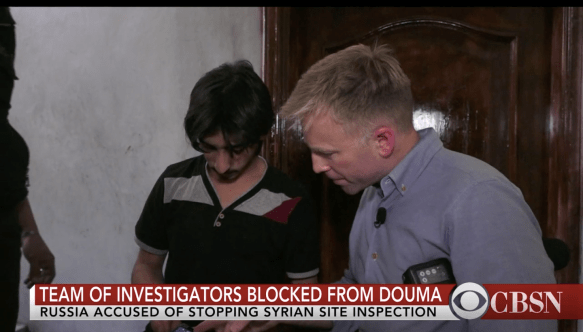

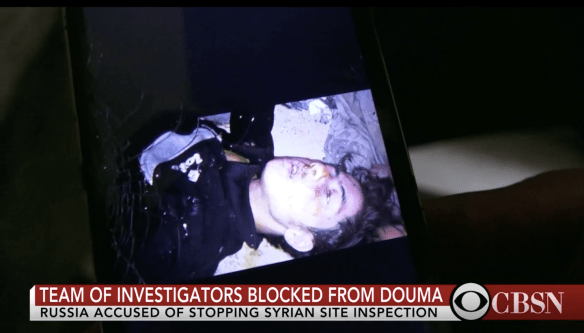

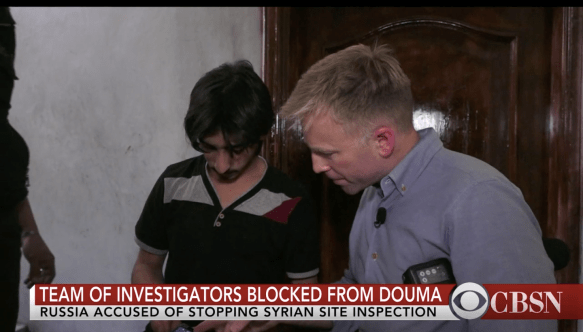

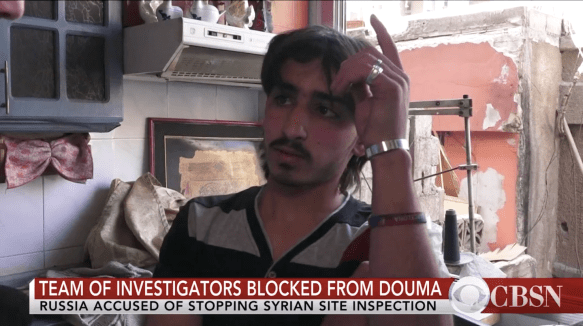

Yet, remarkably, other journalists on the same escorted tour somehow found other people whose accounts contradicted Fisk’s doctor and jibed with those other testimonies. Whether they were also ‘a short walk away’ I don’t know; but here are two of them speaking to Seth Doane of CBS News:

Today we made it to that very house where that suspected chemical attack took place. “All of a sudden some gas spread around us,” this neighbour [below] recounted. “We couldn’t breathe. It smelled like chlorine” …

Nasser Hanen‘s brother Hamzeh is seen in that activist video, lifeless and foaming at the mouth.

In the kitchen he told us how his brother tried to wash off the chemicals. [Asked how the chemicals got there], “The missile up there,” he pointed, “on the roof.”

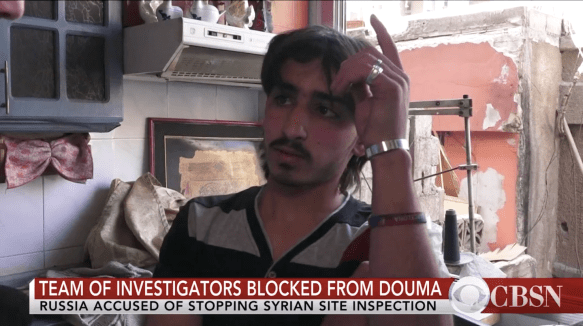

A Swedish journalist, Sven Borg, also recorded his interview with Nasser Hanen (I’ve taken this from Scott Lucas‘s account here – the translation is by Hugo Kaaman):

We were sitting in the basement when it happened. The [missile] hit the house at 7 pm. We ran out while the women and children ran inside. They didn’t know the house had been struck from above and was totally filled with gas. Those who ran inside died immediately. I ran out completely dizzy….

Everybody died. My wife, my brothers, my mother. Everybody died. Women and children sat in here, and boys and men sat there. Suddenly there was a sound as if the valve of a gas tube was opened. It’s very difficult to explain. I can’t explain. I don’t know what I should say. The situation makes me cry. Children and toddlers, around 25 children.

It should be obvious that none of this adds up – that these concerted manoeuvres conspicuously fail to produce a coherent narrative – but, as Jonathan Cooke might say, it doesn’t have to. All it has to do is sow doubt and spread confusion. In an astute attempt to track the interlocking yet contradictory false-flag operations supposedly in play after the Douma attack, Uri Friedman cites Peter Pomerantsev, who explained that the larger (in his case, Russian) project

doesn’t just deal in the petty disinformation, forgeries, lies, leaks, and cyber-sabotage usually associated with information warfare. It reinvents reality, creating mass hallucinations that then translate into political action. … We’re rendered stunned, spun, and flummoxed by the Kremlin’s weaponization of absurdity and unreality.

‘If nothing is true,’ Pomerantsev warned, ‘then anything is possible.’

Perhaps the ultimate horror is that this strategy is not confined to Putin, Assad and their proxies. It also describes the view of an American president who treats the world as a stage for reality TV.

The bottom line

You will draw your own conclusions from all this, but for my part I am persuaded that hundreds of people were killed or injured by chemical weapons in Douma and that there are compelling reasons for suspecting that the Syrian Arab Army was the culprit.

And yet the military response by the US, France and the United Kingdom has a strong whiff of the theatrical about it. Its legitimacy was undercut by the decision to short-circuit the formal, forensic investigation by the OPCW (though I concede that this faced – and continues to face – considerable obstacles, that it is prohibited from assigning responsibility, and that these considerations diminish the reach of the investigation). The effectiveness of the tripartite response is also highly questionable – whether as sanction or deterrent – and the appeals by the allies to humanitarianism and civilian injury ring spectacularly hollow in the face of their indifference to every other form of violence inflicted on populations inside Syria and to the plight of Syrian refugees who have fled the killing fields.

I also believe that the frenzied efforts by so many to defend Syria and its allies from every criticism, to blind themselves to the repressive and violent constitution of the Syrian state, and to close their ears to the cries of its victims is utterly reprehensible. There is the stench of the theatrical about this too – not of greasepaint but of sulphur. How many chemical weapons ‘manufactories’ have to be discovered, how many film stills unearthed, how many contrary witnesses stumbled upon before those using this ‘evidence’ ask serious questions about its provenance, probity and meaning? To find an utter disregard for truth on the far right is no surprise; to find it on the left is a source of shame. There are questions to ask about the Douma attack and the response by the US and its allies, as I have sought to show, but the mental and moral gymnastics some of these commentators perform simply astound me. Their controlling assumption seems to be that it is impossible to object to the actions of the US and its allies and also to the actions of Russia, Syria and their allies. This really is what Leila al Shami calls ‘the anti-imperialism of idiots‘.

It’s still a long way off, but I can’t wait to share the news of a new book from Joseph Pugliese: Biopolitics of the More-Than-Human: forensic ecologies of violence (Duke University Press, due in November).

It’s still a long way off, but I can’t wait to share the news of a new book from Joseph Pugliese: Biopolitics of the More-Than-Human: forensic ecologies of violence (Duke University Press, due in November). Many readers of this blog will know Joseph’s State violence and the execution of law: Biopolitical caesurae of torture, black sites, drones (2013), also one of my favourites, but this is a radical extension and even transformation of those arguments.

Many readers of this blog will know Joseph’s State violence and the execution of law: Biopolitical caesurae of torture, black sites, drones (2013), also one of my favourites, but this is a radical extension and even transformation of those arguments.