This is the second in a series of posts on East Ghouta (Damascus); the first, providing essential background, is here.

The logic of the siege warfare pursued by Syria and its allies has been to cordon off areas under rebel control; to restrict, disrupt and ultimately prevent movement across the siege lines (including food, fuel and medical supplies); to subject the besieged population to sustained and intensifying military violence from aircraft, ground ordnance (artillery, missiles and mortars) and sniper fire; and to outlaw the provision of medical aid to those inside the besieged areas and limit the evacuation of the sick and wounded.

You can find more on the reincarnation of siege warfare as a tactic of counterinsurgency in later modern war here, here, here and here.

Precarious lines and precarious lives

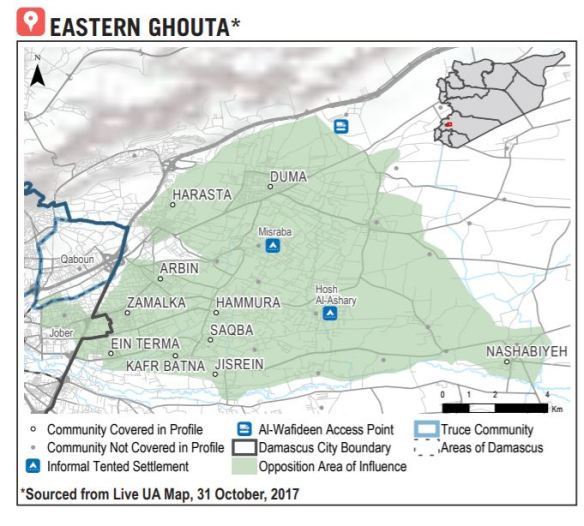

In this post I examine the siege economies that emerged in East Ghouta from 2012 and their transformation over the next six years (to March 2018).

The restrictions on movement imposed on the besieged population varied in time and space. This map from the New York Times plots incidents between the Syrian Arab Army and various rebel groups from September to November 2012:

As the clashes intensified the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) and its allies established a series of checkpoints in November-December to regulate the movement of people and supplies between Damascus and East Ghouta, though Amnesty International reported that anyone crossing ‘ran the risk of being detained or shot by government snipers’ and there were also reports of goods being confiscated or pilfered. Access to those crossing points was also controlled from within the besieged area by armed opposition groups whose actions affected both entrance and exit.

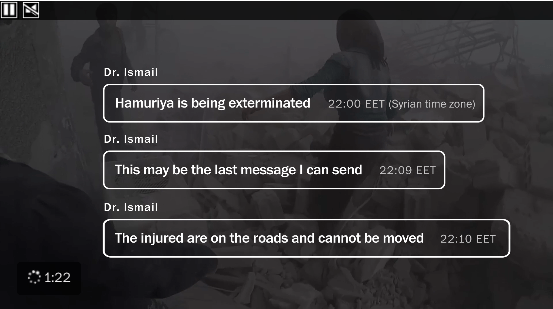

The restrictions increased, along with the dangers, until in August 2013 the two crossing points at al-Mleha and Douma were closed by the SAA. One woman recalled how she ‘didn’t understand’ what was happening when the road out of Ghouta was first blocked::

What did it mean that we were trapped? Then stores’ shelves gradually went empty. Food, fuel, the most basic essentials … everything began to vanish.

But some trucks were still allowed through a third crossing point at al-Wafideen, and the ensuing geography of closure was intricate.

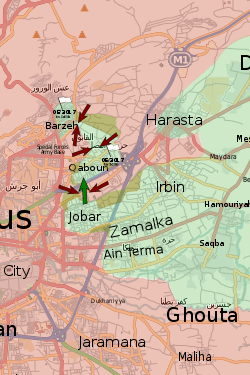

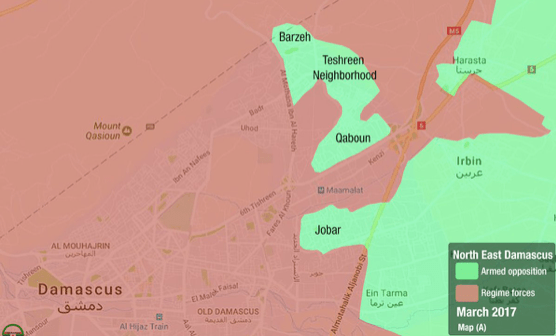

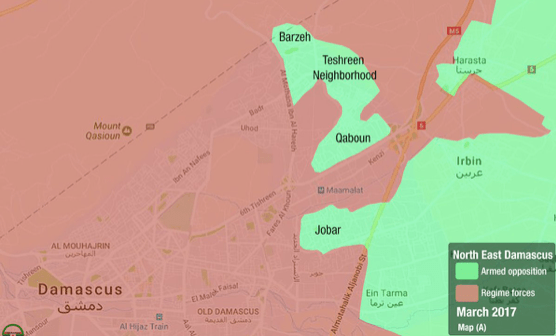

A series of semi-clandestine routes was established between East Ghouta and the suburban towns of al-Qaboun and Barzeh on the other side of the Damascus-Homs highway; an uneasy truce was concluded with rebels in those two towns in January and February 2014, and these routes became vital conduits for smuggling goods into East Ghouta.

People in al-Qaboun and Barzeh relied on conditional access to regime-controlled neighbourhoods beyond the checkpoints. ‘The residents of al-Qaboun and Barzeh live as though they are trapped in a limbo,’ wrote Rafia Salameh, ‘at the mercy of checkpoints.’

The ʻmoodʼ of these checkpoints is measured in the distance between the guards’ pockets – as they are hungry and poor – and their strict application of the law within the presence of superior officers, punishing those who try to smuggle past them simple materials for survival…

Lighters, batteries, light bulbs and any other electrical devices are forbidden. Salt and citric acid, which may be used in the manufacture of explosives, are also forbidden. Gas, milk bottles, and diapers are allowed through if the family carries around the proper documentation in which checkpoint transits are recorded by date, to prove they are not smugglers. However, all these regulations frequently fell silent by paying a bribe at the Barzeh checkpoint.

Salim, a 13-year-old young merchant of sugar says: “They beat us and chase us when the main officer is present.” He went on to explain how his sales decisions are driven by what he can or cannot afford to pay at the checkpoint. His profit per kilogram of sugar is 100 Syrian pounds (SYP), or $0.20 on the black market. He can carry eight kilograms of sugar, and he dips into his profits to purchase a pack of cigarettes for the security officers to allow him through their inspection. The cigarette pack costs 300 SYP, or $0.60. That means he ends the day with less than 500 SYP of profit, which amounts to one US dollar.

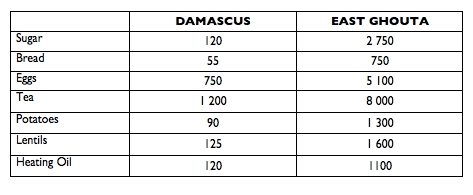

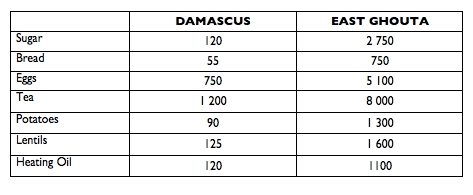

Some of these goods ultimately found their way through the tunnels into East Ghouta, but the price differentials between Damascus (which was not without economic problems of its own) and the Ghouta were stark. Aron Lund posted this chart for March 2015 (prices are all in Syrian Pounds):

On 17 February 2017 the Syrian Arab Army backed by the Russian Air Force opened a new offensive against al-Qaboun (below) and Barzeh and eventually sealed them off from the Ghouta.

The only route that remained open was the al-Wafideen crossing; it had been subjected to intermittent, temporary closures, but on 21 March 2017 it too was finally sealed. The siege of East Ghouta immediately became absolute until the cordon was breached by the renewed SAA offensive in February 2018 and, the following month, by evacuation corridors for the besieged population.

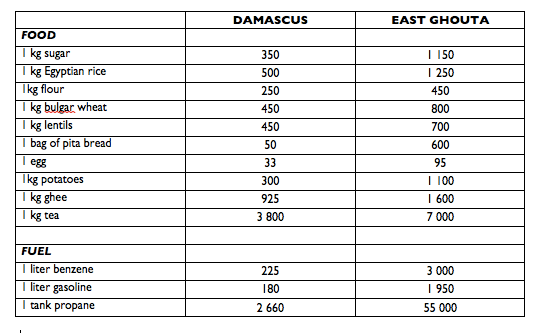

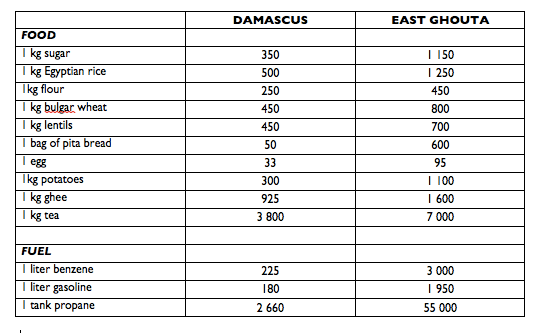

The closure of al-Wafideen had a catastrophic effect. Here is a second price comparison, this time for May 2017 (when the exchange rate was 500 SYP to $1):

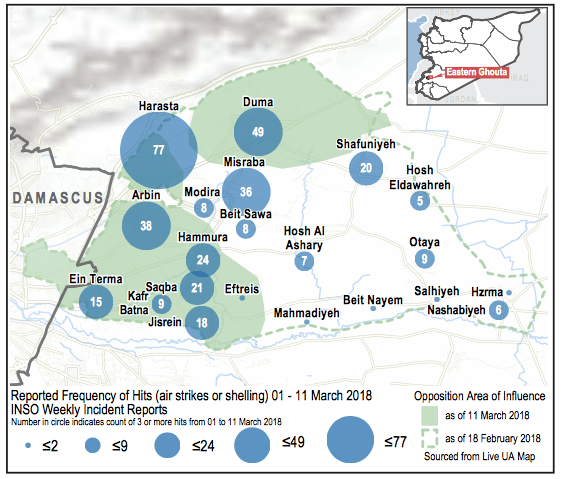

Such price comparisons are inevitably difficult and shot through with all sorts of difficulties, but similar data on food security from the World Food Programme makes it clear that price inflation on this scale made life immensely precarious for those inside the besieged areas – lives then made even more precarious by the escalation of military and paramilitary violence (my next post) and the disruption of medical provision (my final post in this series). According to the WFP in October 2017:

Since the Al-Wafideen crossing closed in September, all food supply routes to eastern Ghouta have been completely closed. Food prices have soared as a consequence, with particularly grave consequences for the poorest and most vulnerable people. During the WFP market assessment conducted in Kafr Batna (in eastern Ghouta) at the end of October, the remaining food stock was found to be very limited, with severe shortages of staple foods such as rice, pulses, sugar and oil.

Based on the market assessment data, the cost of the standard food basket in October 2017 reached SYP327,000, which is 204 percent higher than in September and more than five times higher than in August 2017 (before the crossing closed). The eastern Ghouta food basket currently is almost ten times more expensive than the national average.

According to key informants, the only available cooking fuel in eastern Ghouta is liquid melted plastic, which costs SYP 3,500/litre – ten times more than the national average price of diesel. Some households also reported burning animal remains and even used diapers to boil vegetables.

A bundle of bread in Kafr Batna is being sold at SYP2,000, which is more than 35 times the average price in accessible markets.

Food security is likely to deteriorate rapidly in the coming weeks if the siege continues. It is estimated that food stocks will be totally depleted by end November 2017.

Local resources and improvisations

Faced with the shortages and high prices imposed by the siege, the people of East Ghouta had limited resources to fall back on (see my previous post here), and these contracted sharply after the Syrian Arab Army finally seized control of the rich agricultural lands in the south of the Ghouta (the Marj) in May 2016, near the start of the harvest season. People throughout the besieged area were forced to improvise and to devise ever more exacting economies.

The survival strategies listed by the WFP included reducing the number of meals, reducing portion size and limiting adult consumption, but once the siege became absolute – crossings closed, tunnels blown – many were reduced to far worse than those. The designation of East Ghouta as one of four ‘de-escalation zones’ during the summer of 2017 only opened what Reuters called ‘the doors of starvation’:

‘When people in the Ghouta learned of the deal and thought it would bring relief, many began using up their food reserves at home, said Khalil Aybour, head of the local council in the town of Douma. “After they saw it was all rumors,” he said, “the misery grew immensely.”

Here is a report from November 2017:

The sight of a woman weeping as she drags her malnourished children into a clinic is not rare in eastern Ghouta…. But when one mother told Abdel Hamid, a doctor, that she had fed her four starving children newspaper cutouts softened with water to stop them from screaming into the night, even he was stunned. “I could try to describe to you how terrible the conditions are in which we are living, but the reality would still be worse,” [he] said.

Another young widow described how she rationed food between her three young daughters:

My girls take turns eating now. We barely have any food so each one eats one meal every three days. It breaks my heart because they go to bed hungry and wake up with no energy.

Stories like these are what lie behind the distanced prose of an interagency assessment of food security conducted for the World Food Programme that same month, which reported:

Due to the lack of available food and the high food needs, a food basket meant to support a five member household for a month [supplied by the UN] is being shared among six different households (approximately 30 people).

Due to lack of staple food commodities and severe shortfall of cooking fuel (firewood, diesel and gas) in addition to their high prices, residents have been reduced to subsist on raw vegetables such as maize corn, cabbage and cauliflower with no more than one meal per day. In many households with multiple mouths to feed, priority is given to children with adults often skipping entire days without eating. Some households are even resorting to rotation strategies whereby the children who ate yesterday would not eat today and vice-versa.

Cases of severe acute malnutrition among children were identified by the UNICEF team…

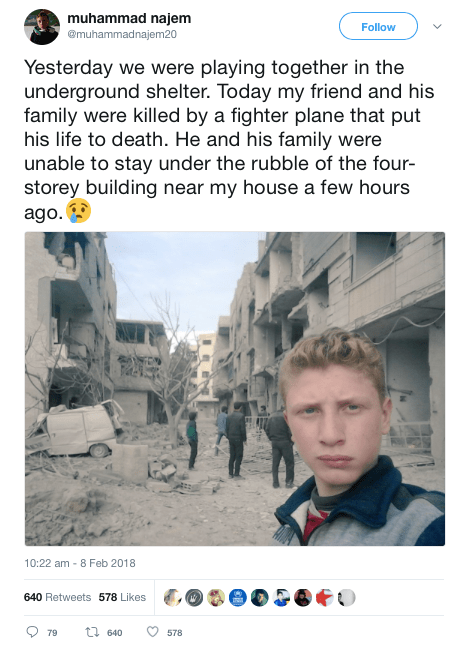

Three months later, once the offensive started in deadly earnest, the situation deteriorated still further. By March 2018, when thousands of people were huddled in basements and cellars sheltering from the incessant bombing and artillery fire, some of those that could find food were reluctant to eat in front of other people in the face of such widespread hunger. Others shared what little they had.

In fact food was the central concern throughout the siege. In the beginning some residents started to grow vegetables on their roofs to supplement local production and avoid the soaring prices in local markets:

“The blockade has forced us to find alternatives, especially in towns like al-Buwaidah, hijjera, and al-Sbeneh, where all the surrounding farming lands were destroyed, and many farmers were killed,” said Ahmad Abu Farouq, a 19-year-old who lives in Ghouta with his family of nine.

Ahmad said he and his family have turned their 1,600-square-foot (150 sq meter) rooftop into a year-round farm, planting zucchini and pumpkin in the winter, and lettuce and parsley in the summer [see the image below]. “I throw in a mix of eggplant, peppers and cucumbers when I can,” he added.

Eastern Ghouta is frequently and heavily hit by government airstrikes. To protect themselves and their crops, according to Ahmad, most people who have chosen to take up alternative farming find ways to hide their box planters so as not to make them entirely visible from up above.

This proved to be a short-term solution: when the Assad regime cut electricity supply to the Ghouta it had serious spill-over effects, and ‘on rooftops, as in the agricultural fields, the [consequent] lack of an irrigation system providing clean water caused the end of this semi-autonomous way of surviving the siege.’

This proved to be a short-term solution: when the Assad regime cut electricity supply to the Ghouta it had serious spill-over effects, and ‘on rooftops, as in the agricultural fields, the [consequent] lack of an irrigation system providing clean water caused the end of this semi-autonomous way of surviving the siege.’

So fuel was a second major concern, but there too there were improvisations. Mark Hanrahan and Bhassam Khabieh described an elaborate scheme in Douma to convert plastic waste into fuel. Using methods he learned from YouTube videos, Abu Kassem and his family collected plastic bottles, rubble from damaged buildings, plastic cooking utensils, even plastic water and sewage pipes; they burned them all in a makeshift refinery, and sold the gas for domestic and commercial use or condensed the gas and refined the liquid into fuel for generators and vehicles.

At its height the workshop was running 15 hours a day six days a week; on an average day it burned 800 – 1,000 kg of plastic waste to produce around 850 litres of fuel. This was a dangerous, noxious business:

“Working here is very tiring, but we feel that we are providing a great service to people. I have been working here for a short time and have begun to adapt to the atmosphere here,” said Abu Ahmed, 28, [one] of the workers.

And the products were snapped up:

“When the siege began on eastern Ghouta at the end of 2013 fuel prices rose madly and we were no longer able to water crops as in the past,” Abu Firas, 33, an agricultural worker in the district told Reuters. “When we started producing local fuel, and water engines could be powered by this fuel, … life returned to agricultural land.”

Abu Talal had the same idea:

“We get plastic materials from areas and buildings that are deserted after being shelled by the regime forces. We collect all the plastic we find, such as water tanks and drainage pipes.”

After Talal and his team gather the plastic, they cut it into smaller pieces and put 50 kilograms in each barrel, along with 20 meters of piping to cool the water that runs in and out of the barrel. They contain narrower tubes, which contain the fumes that come from the burned plastic. Then they light a fire.

“It takes two to three hours to extract as much as possible from one batch of plastic,” he says. “In the last stage, we get the temperature to 100 to 115 degrees to extract a kind of diesel. The temperature must be accurate for the diesel to come out and for it to burn well, so it can be used in cars and motorcycles.”

Ammar al-Bushy described a similar operation at Erbin here. ‘People are aware that the fuel extracted from burning plastic [is of a lower] quality than that extracted from oil,’ he reported, and it ’causes long-term problems for engines, but it meets the purpose for people living in a dire situation, in addition to the lower cost than fuel extracted from oil.’

The economics of the operation were explained by Abu Hassan:

The economics of the operation were explained by Abu Hassan:

“Gasoline reached the price of 4000-4200 Syrian Pounds ($20-$21), and the amounts available were minimal. However, we found a substitute by heating plastic and extracting methane, gasoline, and diesel.

“The price of diesel was 3200-3500 Syrian Pounds ($16-$18.50) per liter, which is considered very expensiv. So people were no longer able to purchase it, but after we started operating on plastic and started extracting diesel from it, the price decreased to 1200-1500 SP and it became more available.”

There were other manufactories too: there is a remarkably detailed analysis of the manufacture of weapons by Jaish al-Islam here, including improvised mortars, rockets, grenades and rifles.

But my focus here is on those resources basic to civilian survival in the besieged area. There were all sorts of other substitution strategies in East Ghouta – I’ll deal with the improvisation of medical supplies and anaesthetics in the final post in this series – but the two examples I’ve provided show concerted attempts to devise solutions to the supply shortages and high prices that were the immediate products of the tightening siege.

Those economic conditions were also affected by cross-cordon transactions: by merchants who were allowed to bring goods in through the al-Wafideen checkpoint, and by smugglers who (until the offensives against Barzeh and al-Qaboun) operated a series of clandestine tunnels that gave access to markets on the suburban fringe. I’ll consider each in turn, but in both cases there was an elaborate administration of precarity: an apparatus of permissions and permits, exactions and kick-backs, through which the local economy was manipulated and political and (para)military relations were managed.

There was another set of cross-border transactions: these were non-commercial flows of humanitarian aid. The Syrian government put in place an intensely bureaucratic system to regulate aid convoys which was also part of the administration of precarity. It proved to be (and was intended to be) so restrictive that these flows had precious little sustained impact on economic conditions in Ghouta. But, as I’ll show, these transactions were entangled in a wider and intrinsically partisan geography of precarity that magnified the marginality of Ghouta and effectively enlarged the power of the regime to dictate the terms of its ‘surrender or starve‘ strategy.

Merchants and the Million Checkpoint

One of Amnesty International‘s informants described how the importation of food into East Ghouta was slowly restricted:

By April 2013, you were not allowed to take any food into Eastern Ghouta. Security forces would beat women and men when they found bread or vegetables hidden in the boot of the car or under clothes. As I passed by a checkpoint, I remember seeing food piled up and people being beaten up or humiliated. The Syrian authorities did not allow any bread, vegetables, fruits, pasta, sugar or eggs to enter.

By April 2013, you were not allowed to take any food into Eastern Ghouta. Security forces would beat women and men when they found bread or vegetables hidden in the boot of the car or under clothes. As I passed by a checkpoint, I remember seeing food piled up and people being beaten up or humiliated. The Syrian authorities did not allow any bread, vegetables, fruits, pasta, sugar or eggs to enter.

As individual transactions were banned, so selected merchants were allowed to organise much larger shipments. The al-Wafideen crossing became the most important external source of food and fuel for East Ghouta – often described as the ‘lung’ through which the Ghouta breathed – and the central figure in commercial transactions through the checkpoint was Mohyeddin al-Manfoush (‘Abu Ayman’), one of what the Economist called ‘Syria’s new war millionaires’: the ‘dairy godfather’.

Before the war Manfoush lived in Mesraba near Douma, where he owned a small herd of cows and a cheese factory, and traded as al-Marai al-Dimashqiya (Damascus Pastures). Once the siege began he quickly struck a deal with the Syrian government. The Economist again:

He began to bring cheap milk from rebel territory in Eastern Ghouta to regime-held Damascus, where he could sell it for double the price. The regime received a cut of the profit. Mr Manfoush reinvested his share. He snapped up the region’s best cows and dairy machinery from farmers and businessmen whose livelihoods had been hammered by the siege. As the business evolved, the trucks that left Ghouta with milk and cheese came back laden with the barley and wheat he needed to feed his growing dairy herd there and run the bakeries he bought.

It was immensely profitable; with a captive market of 400,000 people and runaway prices Manfoush not only expanded his business (under the umbrella Manfoush Trading Company) but also moved to a new house in Damascus and even established his own private militia.

Others profited too. The security forces controlling the crossing (above, in February 2018) received ‘extra payments’ from Manfoush; there have been reports that they charged 200-300 Syrian pounds ($1 – $1.40) and sometimes as much as 750 Syrian pounds for each kilogram of goods passing through the checkpoint. Local people came to refer to al-Wafideen as ‘the Million Crossing’ because it supposedly generated one million Syrian pounds per hour in bribes for its soldiers and security officers. In March 2015 researchers were told a fee of one million Syrian pounds allowed a vehicle to pass through the checkpoint. And Manfoush dispatched convoys not single trucks:

But the kickbacks almost certainly went much higher than those operating the checkpoint. Roger Asfar has claimed that Manfoush’s web of companies is linked to the business empire of President Assad’s brother, Maher al-Assad (who also usefully heads the Republican Guard). Be that as it may, the regime had more than a commercial interest in Manfoush’s transactions because it was able to leverage its control over al-Wafideen and ‘exploit its ability to turn trade on and off in order to sow enmity among [different] rebel [groups].’

The state’s ability to goad its enemies in this way depended not only on the rivalries between different rebel groups, however, but also on those groups’ own stakes in the siege economy. These derived, in part, from the revenues generated through their ancillary checkpoints. Many informants testified that another set of ‘fees’ were exacted there, though what eventually became the major rebel group in Douma, Jaish al-Islam [JAI], denied having any stake in Manfoush’s operations at al-Wafideen:

“Manfoush does not serve the Islam Army [JAI], he serves the Ghouta in its entirety,” said the Islam Army official Mohammed Bayraqdar. “Our interests are in harmony with the interests of the people and our relationship is merely that of facilitating his services. If there were another person [who performed the same function], we would provide the same services to him in return for his services to the people of the Ghouta.”

Those ‘facilitations’ and ‘services’ involved granting Manfoush’s convoys safe passage into East Ghouta, and it seems highly unlikely that this was a purely philanthropic gesture. In June 2015 one of Amnesty International‘s informants explained:

Since the end of 2014, the Army of Islam [JAI] has controlled the supply route from al- Wafedine camp and Ajnad al-Sham, the underground tunnels in Harasta. The Army of Islam is responsible for regulating the prices. During the winter, the Army of Islam collects most of the food supplies from the market, increasing the prices threefold. You sleep one night and wake up the next day to find there is no food and prices are high. The Army of Islam in collaboration with suppliers store food and non-food items in [its] warehouses.

Siege Watch was even more blunt in its assessment for May-July 2017: ‘the corrupt trading monopoly run by al-Manfoush at the al-Wafideen checkpoint lined the pockets of the Syrian miilltary and JAI’.

There is no doubt that Jamash al-Islam’s provision of ‘services’, whether corrupt or not, was far from disinterested: facilitating the importation of food, fuel and other supplies gave it leverage over the besieged population. It was able to extend its control over the local labour market in Douma – determining which shops were allowed to open, for example – and gave those on its payroll privileged access to imported goods from its own warehouses. JAI was not the only group to take advantage of the siege economy. In Harasta, Fajr al-Umma reportedly ‘gave away free food and a tank of propane … in [an] attempt to strengthen its popularity in the area.’ In short, food and fuel became vital currencies not only for the counterinsurgency but also for the insurgency. ‘Joining one of the armed groups can provide a monthly salary of an average of USD 50,’ Rim Turkmani and her collaborators in the LSE’s ‘Security in Transition’ programme (including Mary Kaldor) found, ‘in addition to food parcels.’ And at times, they continued, ‘fighters are only paid in food.’

Putting all this together, Rim produced this diagram which traces the journey of a loaf of bread from Damascus into East Ghouta and shows how extensive was the system of exchange whose fulcrum was al-Wafideen:

Underground economies

In his detailed analysis of the tunnels excavated and operated by the armed opposition groups in the Ghouta, Aron Lund explains:

Apart from the Wafideen Crossing, the Eastern Ghouta has been supplied through a system of secret tunnels and semi-informal frontline crossings. While the crossings can bring in a far greater volume of trade, the tunnels serve to import goods that are restricted or banned by the government (including fuel, medical supplies, and arms), to move people in and out of the enclave, and to challenge and undercut food prices set by the Wafideen monopolists.

Digging the tunnels was difficult and dangerous work – but in a place where the economy was collapsing, where there were so few jobs to be had, and where some rebel groups resorted to more directly coercive methods of recruitment the work proceeded apace:

Men of Douma work in three shifts a day to finish their job, using primitive tools. “Each worker has one meal – either breakfast with an egg and a piece of bread, or lunch with rice and bread. The digging never stops. When we hit a large rock or anything like it, we turn on the generator and use a jackhammer,” said Abdullah, a tunnel digger. When asked about the reason that men take this job and whether it pays well, Abdullah said: “Many have lost their job because of the ongoing war, so we have no means to earn money to buy food. Prices are also very high because of the prolonged siege. They pay around 1,000 Syrian pounds per worker, which covers the price of a kilo of flour….”

“When we first started digging tunnels, we faced many difficulties; however, we found solutions and continued the operation. For example, we pumped oxygen at certain points inside the tunnels, which is very important for the workers. We also set up pillars inside the tunnel to prevent them from collapsing over the workers, which had happened often earlier, and killed and trapped many workers for many hours before we could rescue them,” said Abu Mahmoud.

There were five main tunnels (I’ve taken most of these details and the maps from a report by Enab Baladi‘s Investigative Unit on ‘The economic map of Ghouta‘).

The first (the Zahteh or Central Tunnel) ran 800 metres from Harasta under the Damascus–Homs highway to Qaboun; construction was started by Fajr al-Umma towards the end of 2013, and the tunnel opened the following summer. It soon emerged as ‘the primary [clandestine] artery for the Eastern Ghouta’s siege economy’.

In January 2015 Jaish al-Umma opened a second, parallel tunnel, but Fajr al-Umma soon controlled this route too:

In May 2015 two other rebel groups, Failaq al-Rahman and al-Liwan al-Awwal, dug the so-called ‘Mercy Tunnel’ from Arbin to Qaboun; this was much longer than the previous two (2,800 metres) and wide enough to allow the passage of cars and even Kia 2400 trucks.

In June 2015 Jaish al-Islam constructed a 3km tunnel from Arbin and Zamalka to Qaboun; it too was wide enough to accommodate small trucks.

In September 2015 Falaq al-Rahman joined with Jabhat al-Nusra in Qaboun to establish a third tunnel under its control, the ‘Nour [Light] Tunnel’, from Arbin to Qaboun for foot traffic only.

These were the main tunnels, but several smaller tunnels were dug between the Ghouta and Jobar, and others were dug primarily for (para)military purposes to move personnel, ammunition and armaments. Other tunnels were dug within the Ghouta as defences against air strikes; they served multiple purposes, not least connecting the dispersed facilities of underground field hospitals (more on this in a later post). One SAA informant described to Robert Fisk what he saw when he entered Douma in March 2018:

I have never seen so many tunnels. They had built tunnels everywhere. They were deep and they ran beneath shops and mosques and hospitals and homes and apartment blocks and roads and fields. I went into one with full electric lighting, the lamps strung out for hundreds of yards. I walked half a mile through it. They were safe there. So were the civilians who hid in the same tunnels.

The main cross-line tunnels were used for multiple purposes too: but commercial traffic was always an important consideration.

I describe this as commercial not only because the goods were sold at stores inside Ghouta but also because the tunnels provided the groups that controlled them (often through nominally civilian front organisations or ‘foundations’) with income and resources. This caused considerable jockeying between them; Aron Lund provides a superbly detailed analysis of the rivalries, deals and counter-deals that ensued.

The tunnels were considerable undertakings. The director of the organisation set up to operate the Mercy Tunnel told Enab Baladi that it cost 30,000,000 Syrian Pounds each month to cover ‘the expenses of nine Kia 2400 trucks that work between 3 p.m. and 6 a.m. and the salaries of 450 employees, including drivers, workers, administrators, officials and custodians, in addition to security officials.’

There were three streams of commercial transactions. The first involved the passage of civilians and, like all movement through the tunnels, was closely controlled by the rebel groups. One of Enab Baladi‘s informants outlined the rules:

Those passing through the tunnels must be born before 1970, since the factions are in need of young fighters.

The person passing must provide clearance from the Unified Judiciary, to prove that there are no cases outstanding against him or her, and a clearance from the Housing Bureau.

Fighters must provide an official permit (below) from their faction.

All documents must be submitted to the Crossing Office, which will assign the person a date to pass.

Medical emergencies are exempted from the waiting period, but must provide a report from the Unified Medical Bureau.

Under no circumstances are weapons allowed to leave Ghouta.

No goods other than clothes and basic supplies are allowed (not to exceed two bags).

Abu Ali described how he and his family made their escape:

The process of applying to use the tunnel, he said, was strangely bureaucratic for such a risky method of escape: He submitted an official request at a Jaish al-Islam office and was informed two weeks later that it had been granted… [He] and three other families granted access to the tunnel started their journey on a bus from the city of Hamouriyya.

“The bus took us to the city of Arbin. In Arbin, the bus took side streets, so that we wouldn’t be noticed. We finally arrived at a house where our identification cards were checked, and our luggage was searched. We were told that we had to be very careful, so no one would discover where the tunnel was,” he said.

The tunnel “was very tight – there was barely enough room for two people to walk side by side and it was about two meters in height. In addition to lights, the tunnel had turbines for ventilation purposes.”

These rules were never set in stone, still less once the co-operation implied by the ‘Unified Medical Bureau’ and the ‘Unified Judiciary’ [established in the summer of 2014] broke down and in-fighting between the groups controlling the tunnels became commonplace. Despite the age restrictions, some of them were willing to allow young people to pay for a permit: the cost varied between 100,000 and 200,000 Syrian pounds. If they wished to escape Qaboun or Barzeh, they would then pay further bribes to the soldiers and security officers controlling the regime’s checkpoints into Damascus.

There was one constant: the rules allowed for the evacuation of medical emergencies but no medical staff – doctors, nurses, pharmacists – were permitted to leave. In fact it seems unlikely that many serious medical cases were evacuated through the tunnels either. They would not have found better treatment in Barzeh or Qaboun, but during the early stages of the truce some patients were allowed to cross from those besieged districts into Damascus. Dr Immad al-Kabbani testified that ‘for a period beginning in September 2014 we were able to evacuate a minimum of 20 patients and their families each week’ through the tunnels (and even ‘to send biopsies from cancer patients to cooperative labs in Damascus for diagnosis’) but by March 2016 the clandestine system was already failing. One cancer patient was allowed to leave for radiation therapy which was unavailable at the Dar al-Rahma Center for Cancer in Ghouta, but her journey turned out to be fruitless:

I received no care at hospitals [in Damascus] so I relapsed and the tumour returned to its previous status. I decided to go back to Eastern Ghouta through the same tunnels to have the chemical doses.

That same month patients were travelling in the opposite direction. A doctor from the Syrian-American Medical Society testified:

Now, as access to Damascus has been cut off, the 35,000 civilians inside Barzeh have extremely limited access to healthcare, and must travel to East Ghouta to obtain treatment. Even the dialysis patients in Barzeh are traveling to East Ghouta [via the tunnels] to obtain treatment with the extremely limited supplies.

For a time the tunnels were a two-way street of sorts for cancer patients: those who needed chemotherapy were treated at the Dar al-Rahma Center in Ghouta, using medical supplies smuggled through the tunnels [below], while those needing radiotherapy were taken through the tunnels to al-Nawawi hospital in Damascus. According to the director of the Dar al-Rahma, ‘after the closure of the tunnels, there is no possibility of providing either of the treatments.’

By the time the tunnels were closed in February 2017 the UN estimated that around 80 patients out of 700 estimated to be in need of urgent treatment had been evacuated from East Ghouta through the tunnels. Some were transferred because there were no specialists available inside the besieged area, others because clinics there had been denied the medicines and equipment needed to treat them. But the numbers were small when set against the extensive record of seriously injured or ill patients being placed on evacuation lists from the Ghouta only to have their doctors’ requests refused or ignored by the Syrian government. Once the tunnels were closed ‘all movement of patients was halted.’

The second stream of traffic involved everyday supplies of all kinds, including food and fuel. Some rebel groups limited their dealings to particular merchants but in every case a tunnel ‘tax’ was levied. The usual fee seems to have been 10 per cent but there were times when 25 per cent and even 45 per cent of the value of the goods was levied. The ‘tax’ was paid in cash or in kind: the different factions maintained their own warehouses and usually gave their own fighters and supporters privileged access to the supplies they skimmed from the shipments. During the first two months that the Mercy Tunnel was in operation, for example, Falaq al-Rahman allegedly ‘filled its warehouses with more than 12 tons of goods, claiming that it had to secure its fighters first.’ As this implies, the totals involved were small – they paled into insignificance alongside the commercial shipments through al-Wafideen – but they provided the armed opposition groups with significant financial gains. Enab Baladi again, citing one of the directors of the Mercy Foundation:

“Everyone finds in the tunnel the perfect opportunity to make money. Since the very first tunnel was completed, Fajr al-Umma, the faction that had dug the tunnel, took control of all incoming goods and sold them for extremely high prices. In 2014, for example, 1kg of sugar was sold for 60-70 Syrian pounds [around 30 cents] in Damascus, but Fajr al-Umma sold it for 3, 500 Syrian pounds [more than $16] within Ghouta.”

These exactions – and the subterranean monopolies that underwrote them – prompted endless negotiations (and worse) between the groups over shared access. Kholoud al-Shami suggested that Jabhat al-Nusra planned the Nour Tunnel explicitly to undercut its rivals, bring prices down, and so boost its support among the besieged population. One local resident told her:

It appears that Nusra’s goal is to reduce the suffering of the besieged residents, who had begun cursing the revolution and the rebels because of Falaq al-Rahman and Fajar al-Umma keeping prices high. All factions want to build up their popular support, which is what Nusra is doing… Local residents have viewed the drastic drop in prices positively and stood in solidarity with Jabhat a-Nusra when Falaq al-Rahman prevented them from selling gasoline at reduced prices when they were still sharing a tunnel.

Similarly, Jaish al-Islam apparently pressured Fajar al-Ummah to lower its prices. It was an intricate and constantly changing story, but running through all these deals was the imbrication of the political with the economic. The attempts to lower prices were all about more than the high-minded desire to ‘reduce suffering’: they were also aimed at boosting support for one faction over another.

The third stream of traffic consisted of medical supplies. I have separated these from other supplies because they were categorically barred from the al-Wafidden crossing; even UN convoys with the appropriate authorisations had them removed at the checkpoint. Yet they were vital. Inside Ghouta doctors were struggling with often catastrophic injuries from shelling and bombing, and doing their best to treat seriously ill patients with chronic conditions (how often we forget that people still get sick in war zones). With no provision possible through the overland crossings, doctors had to use the tunnels. A team from the Union of Free Syrian Doctors worked around the clock in Barzeh to obtain vital medical supplies for hospitals and clinics in Ghouta, but by the time they had paid Syrian Arab Army soldiers controlling checkpoints on the highway and then the tunnel tax – medicines were not exempt but were charged ‘only’ 5 per cent – the costs of even routine medications had soared. Students from the Columbia School of Journalism reported:

By the time all the fees are paid, the price of medical supplies in Eastern Ghouta “is three times higher, sometimes as much as five times, than what’s in the north or south of Syria,” said [Mahmoud] al-Sheikh [director of the Unified Revolutionary Medical Bureau in Eastern Ghouta]. A liter of serum, which is used to help the body replenish lost blood, goes for about $1 in regime-controlled areas (one liter is about one fluid quart). But health workers say they’ve paid anywhere from $3.50 to $10 for one liter of serum brought in from Barzeh.

[Osama] Abu Zayd [a medical equipment engineer with the Union of Free Syrian Doctors] estimates that Ghouta, with its many neighborhoods, needs about 10,000 liters (more than 2,600 gallons) of serum per month.

Whatever came through the tunnels, it was never enough, and all three traffic streams came to a juddering halt as the offensive against Barzeh and Qaboun was renewed. During the winter of 2016-17 the regime sought to amend the terms of the truce, stipulating that the smuggling trade had to stop; then in February 2017 it peremptorily closed the checkpoints so that supplies from Damascus dried up, and within days nothing was moving through the tunnels to Ghouta.

The fighting that followed was protracted and bloody, and thousands fled through the tunnels to find refuge in East Ghouta. But by the end of February the Syrian Arab Army occupied the warehouse concealing the portal to the Zahteh Tunnel, and by the middle of May, when the remaining opposition fighters in Barzeh and Qaboun had surrendered and the population was forcibly evacuated, all the major tunnels had been breached.

State media published videos showing the army cutting the tunnels and carrying out controlled explosions. The ultimate objective was not only to take down Barzeh and Qaboun but ‘to strangle the Ghouta … by closing off the crossings and tunnels,’ a spokesman for Jaish al-Islam explained. ‘Trade through the tunnels has completely stopped.’

The loss of the tunnels triggered panic buying in Ghouta, driving prices still higher, and triggered a new round of fighting between the two major blocs of rebel fighters (Jaish al-Islam based in Douma and Falaq al-Rahman in fractious and as it turned out temporary alliance with Hay’at Tahrir a-Sham, which later became Jabhat al-Nusra, which were based in the so-called ‘Central Section’ to the south and the west).

Residents of the Ghouta demonstrated against the infighting – and, in a displaced and horrifying repetition of the tactics employed by regime’s security forces, Jaish al-Islam opened fire on the crowd – and the deepening tension served only to aggravate the economic crisis. In July 2017 Alaa Nassar reported:

Dozens of recently erected checkpoints and berms split the suburbs [of East Ghouta] in half. For residents trapped inside the Central Section, this means a lack of access to the Wafideen crossing and, therefore, to outside resources.

By September 2017 the Syrian-American Medical Society‘s report on the siege of East Ghouta described a truly dreadful predicament:

In a report for the Middle East Institute, ‘Sieges in Syria: Profiteering from misery‘ (2016) Will Todman summarises the two sets of cross-cordon transactions I’ve described so far – overt commercial transactions through al-Wafideen and clandestine transactions through the tunnels – like this:

It’s an effective summary but, as I now need to show, the bottom line (sic), in which UN convoys are described as ‘an effective means to get goods to civilians at a lower price,’ is problematic.

Aid convoys

Like the commercial convoys of merchandise that were allowed in to East Ghouta, humanitarian aid came in through al-Wafideen (above). Unlike the commercial flows, however, humanitarian aid was rigorously policed, strictly limited and utterly spasmodic. In Douma, for example, which had been under siege since 2013, the first UN interagency aid convoy did not arrive until 10 June 2016 (below). Its 36 trucks provided emergency food, wheat flour, and nutrition supplies for only 17 per cent of the population. Those stocks were supposed to last for one month, but the next convoy did not arrive until 19 October 2016, with 44 trucks carrying food supplies for 24 per cent of the population (baby milk had been removed at the checkpoint). Those supplies were also intended to last for one month, and a third convoy duly arrived at al-Wafideen with supplies for 49 per cent of the population on 17 November 2016. But the mission was aborted because ‘it lacked specific approval needed to proceed without dog searches and unsealing of the trucks.’ The next UN convoy arrived on 30 October 2017.

I have extracted most of these details from a report prepared by Elise Baker for Physicians for Human Rights with the dismally appropriate title Access Denied. The report describes a system of deliberate obstruction of humanitarian aid by the Assad regime that imposed – by design, remember – ‘slow, painful death by starvation’ on populations in areas besieged by its forces: what the report also calls ‘murder by siege’.

There have been two main modalities of obstruction. The first has involved a byzantine process through which UN agencies have been required to obtain formal permission from the government to deliver humanitarian aid. Following the establishment of a joint working group to facilitate (sic) the process in 2014, it was agreed that each convoy would need approval from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and ‘facilitation letters’ from the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Syrian Arab Crescent and (in the case of medical supplies) the Ministry of Health. The process was described by the UN Humanitarian Coordinator as ‘extremely complex and time-consuming’, and matters were not improved by the introduction of additional clearance requirements from the High Relief Committee and the National Security Office.

There have been two main modalities of obstruction. The first has involved a byzantine process through which UN agencies have been required to obtain formal permission from the government to deliver humanitarian aid. Following the establishment of a joint working group to facilitate (sic) the process in 2014, it was agreed that each convoy would need approval from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and ‘facilitation letters’ from the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Syrian Arab Crescent and (in the case of medical supplies) the Ministry of Health. The process was described by the UN Humanitarian Coordinator as ‘extremely complex and time-consuming’, and matters were not improved by the introduction of additional clearance requirements from the High Relief Committee and the National Security Office.

After repeated protests from the UN the Syrian government finally agreed to ‘simplified procedures for the approval of interagency convoys across conflict lines‘ in March 2016, that should have reduced an eight-step process to a two-step process, with all approvals (or refusals) being issued within seven working days. In practice, the two-step became a ten– or even eleven-step process. In January 2017 the UN Security Council was advised of ‘subsequent administrative delays on the part of the government, including in the approval of facilitation letters, approval by local governors and security committees, as well as broader restrictions by all parties [that] continue to hamper our efforts’ to deliver humanitarian aid to besieged populations. Even with approvals from the authorities in Damascus, protocols were routinely violated at checkpoints. Stephen O’Brien elaborated:

We continue to be blocked at every turn, by lack of approvals at central and local levels, disagreements on access routes, and by the violation of agreed procedures at checkpoints by parties to the conflict. Are these important? Yes. We can’t – and if I may quote – “just plough on” or “just get on with it” as I’ve heard one member sitting around this say table to me. Because if one brave aid worker drives through the checkpoint without the facilitation letter and the command transmitted down the line, the check-point guard or their sniper takes the shot.

In a statement two months later he bluntly declared: ‘The current bureaucratic architecture is at best excessive and at its worst, deliberately intended to prevent convoys from proceeding.’

The second modality of obstruction was to withhold permission altogether. The chart below was compiled for PHR’s Access denied; notice the substantial differences between the populations for whom the UN requested access and the populations for whom access was approved, a difference that was the product of both outright rejection and a calculated failure to respond.

Notice too the still smaller population eventually reached by the aid convoys:

From May through December 2016, on average, Syrian authorities authorized UN interagency convoys to deliver aid to approximately two thirds of the besieged and hard-to-reach populations that UN authorities requested access to each month – a figure which, in itself, represents a fraction of the entire besieged and hard-to-reach population. However, UN convoys only reached 38 percent of that smaller approved population, due to additional approval procedures and other delays imposed overwhelmingly by government officials… At worst, this pattern reflects an effort by Syrian authorities to appear cooperative while still ensuring that access to besieged areas remained blocked.

The approval process allowed the authorities not only to veto the populations permitted to receive humanitarian aid but also to restrict the amount and composition of that aid. In November 2017, for example, a UN convoy of 24 trucks was allowed in to Douma – the first since August – with food for an estimated 21,500 people (the original request had been for supplies for 107,500); medical supplies had been removed from the convoy. In March 2018 another, much delayed convoy reached Douma with food for 27,500 people (below); deliveries were interrupted by renewed shelling and 10 of the 46 trucks were forced to return with their loads. Marwa Awad, who accompanied the convoy with the World Food Programme, described what she found:

Volunteers gathered to help offload the aid from the trucks, including WFP’s wheat flour which the men were offloading into underground cellars. Speaking with the local council, we learned that there were more than 200,000 people in Douma, many of them displaced from nearby villages and other areas within Eastern Ghouta, and all of them needing food and medicine….

Leaving the devastation above, we took a long and narrow staircase deep into Douma’s underworld: a network of basements that has become fertile ground for disease and infection. Many residents are forced to live underground, crammed together in packed spaces to avoid airstrikes…

There we met Mustafa, a man in his twenties.

“The food aid trickles in very slowly, drop by drop. Many families here are struggling. I hope whoever is hungry gets help,” he said. Because of the increasing demand for food and limited quantities allowed inside, residents of Douma have had to split the food assistance WFP delivered during an earlier convoy in order to reach as many people as possible.

The convoy took place at the height of the final military offensive against the Ghouta: yet the World Health Organisation said that Syrian government officials had ordered the removal of 70 percent of the medical supplies it had prepared for the convoy, including all trauma kits, surgical supplies, dialysis equipment and insulin.

The control exercised by the Assad regime over humanitarian aid derived not only from formal procedures, or the subsequent ‘deletions’ and on occasion, even contamination of supplies at checkpoints; it also depended on the system of clandestine intelligence built in to the architecture of the authoritarian state. The head of one UN agency working out of Damascus told one US/UK investigation team:

We were spied on, followed, our computer traffic was monitored, our notebooks stolen, they knew what we were doing. I’m not sure anyone appreciates how hard all of this was . . . the daily grind of getting a tiny concession of access or movements of goods. The SARC [Syrian Arab Red Crescent] were used as a proxy to control and spy on us and contain us.

So many controls. And yet UN Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014) and 2258 (2015) authorized the unconditional delivery of humanitarian assistance, including medical assistance, to besieged and hard-to-reach communities countrywide. The emphasis is mine; the wording is the UN’s. But the Assad regime clearly called the shots and imposed the most exacting conditions on the delivery of humanitarian aid to besieged areas like the Ghouta. The UN even deferred to the Syrian government over the identification of what constituted a siege; its mappings of besieged and ‘hard-to-reach’ areas were far more restrictive than those conducted by Siege Watch or the Syrian-American Medical Society. Its in-country contracts had to be approved by the government, and not surprisingly many of them – individually worth tens of millions of dollars for accommodation, trucks, fuel, and cellphone service – were with businesses closely tied to the Assad regime. As Reinoud Leenders put it, ‘the Syrian regime’s aggressive assertions of state sovereignty have locked UN aid agencies into a disturbingly submissive role.’

So many controls. And yet UN Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014) and 2258 (2015) authorized the unconditional delivery of humanitarian assistance, including medical assistance, to besieged and hard-to-reach communities countrywide. The emphasis is mine; the wording is the UN’s. But the Assad regime clearly called the shots and imposed the most exacting conditions on the delivery of humanitarian aid to besieged areas like the Ghouta. The UN even deferred to the Syrian government over the identification of what constituted a siege; its mappings of besieged and ‘hard-to-reach’ areas were far more restrictive than those conducted by Siege Watch or the Syrian-American Medical Society. Its in-country contracts had to be approved by the government, and not surprisingly many of them – individually worth tens of millions of dollars for accommodation, trucks, fuel, and cellphone service – were with businesses closely tied to the Assad regime. As Reinoud Leenders put it, ‘the Syrian regime’s aggressive assertions of state sovereignty have locked UN aid agencies into a disturbingly submissive role.’

A report from the Syria Campaign – Taking Sides – found that humanitarian aid delivered under the auspices of the UN was disproportionately directed towards areas under the direct control of the Assad regime. Here is the distribution of aid through the World Food Programme – the largest UN agency handling food aid – shortly after the passage of UNSC 2139, revealing what John Hudson described as ‘Assad’s starvation campaign’:

The following month (April 2014) 75 per cent of food aid delivered from inside Syria went into government-controlled areas. Two years later (April 2016) 88 per cent of food aid delivered from inside Syria went into government-controlled territory; once cross-border deliveries from Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey were taken into account – now authorised by further UN Security Council resolutions – the (dis)proportion going into government-controlled territories fell to 72 per cent. But by April 2017 it had increased to 82 per cent.

Still, these raw figures conceal as much as they reveal; humanitarian aid for government-controlled areas has not been subject to the same restrictions, deletions and delays as aid for areas outside the regime’s direct control. Convoys were far more frequent, loads were larger, and medical supplies were not removed. The Assad regime frequently represented aid to areas under its control as both a gift from the government (through granting access to international agencies) and a gift of the government: at its highest levels, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (a central and compulsory actor in these deliveries) is a de facto arm of the state. There was and continues to be an undoubted need for aid throughout Syria, but according to the UN’s own figures 54 per cent of the population in need lived in government-controlled areas in 2016. Accordingly, Taking Sides argues that

The effective subsidy of government areas releases resources that are likely used by the government in its war effort. The UN has enabled one side in the conflict to shift more of its resources away from providing for the needs of its people and into its military campaign.

The official position was always that the UN had to comply with the Assad regime’s predilections and stipulations as a necessary price for access to the besieged areas, but David Miliband (President of the International Rescue Committee) countered that ‘the Assad regime can’t afford to kick the UN out of Damascus [because] the UN is feeding so many of [Assad’s] own people.’

Conversely, the carefully calibrated restrictions placed by the regime on flows of goods through al-Wafideen into the Ghouta amounted to an assertion of continued control over the besieged population. Esther Meinghaus [‘Humanitarianism in intra-state conflict: aid inequality and local governance in government and opposition-controlled areas in the Syrian war’, Third World Quarterly 37 (8) (2016) 1454-82] argues that in those areas where the regime was not able to maintain military control it exercised effective ‘humanitarian control’ by continuing to dictate the parameters within which the population lived (and died). In consequence, like Esther, José Ciro Martinez and Brett Eng [‘The unintended consequences of emergency food aid: neutrality, sovereignty and politics in the Syrian civil war, 2012-15’, International Affairs 92 (1) (2016) 153-73; also available here] describe besieged areas like the Ghouta as spaces of exception. They reveal a persistent attempt by the Assad regime to separate those ‘included in a juridical order and those stripped of juridical-political protections – a separation between life that is politically qualified and one that is “bare” or naked.’ But as José and Brett emphasise, actors inside the Ghouta (and outside) have repeatedly called into question the actions of the Syrian government and its allies and sought to confound them. The political salience of those counter-strategies is itself compromised, they insist, by treating humanitarian aid as a ‘neutral’ and essentially technical matter of alleviating physical distress and deprivation – the register within which UN agencies conceive their interventions – because that is to become complicit in the reduction of besieged populations to ‘bare life’: ‘Those receiving assistance are valued strictly in terms of their biological life not their political voice’ (p. 165).

The administration of precarity

Throughout this essay I’ve written about ‘the administration of precarity’ because – following David Nally‘s wonderful example – the siege economy was administered by multiple actors whose regulations and restrictions made them responsible for delivering precarity to the besieged population. That the Assad regime and its allies had a direct interest in doing so followed directly from their strategy of ‘surrender or starve’, and there was an elaborate web of exactions and extortions reaching from the highest levels of the state down to the foot soldiers who controlled the checkpoints and crossings. The rebel groups were involved too, but they had a more direct interest in the subterranean smuggling economy, levying fees in cash or in kind on flows through the tunnels to boost their coffers and secure their own supporters. But the United Nations and its agencies were also culpable in acceding to the demands of the Assad regime, allowing it to funnel most humanitarian aid to areas under its control and condemning the civilian populations in besieged areas to half-chance lives of ever increasing precarity.

Yet precarity does not mean passivity, and a ‘siege economy’ is always more than a political economy: it is also and always what E.P. Thompson would have called a moral economy. The rebel groups in the Ghouta were chronically incapable (or uninterested) in finding common ground, and their support amongst the besieged population was uneven and variable. As the siege wore on, protests against their exactions and impositions – and the infighting amongst them – multiplied. For all that, many (and probably most) civilians remained opposed to the Assad regime, and we should remember too that the war emerged out of the violent response of the state to peaceful protests by ordinary people in the Ghouta and elsewhere calling for democratic reforms. This matters because as I worked on this essay – watching the videos, reading the reports, unearthing the testimonies – I became aware of an extraordinary resilience and communal solidarity forged within the population. I think of the ingenuity of the rooftop farmers, the fuel distillers, and the makers of gauze and medicines; the dedication of the doctors, nurses, ambulance drivers and rescue workers faced with so many grievously wounded and seriously ill people; the courage of mothers sharing blankets and what little food they had and singing songs and sharing stories as they huddled with their children in the crowded basements sheltering from the bombs and missiles (see here).

I wrote those words last night; this morning I read this moving letter from the Syria Campaign on ‘Leaving Ghouta‘:

Over the past five years, Ghouta has faced terrible violence including the sarin gas chemical attack that took the lives of hundreds in their sleep. And despite it all they have taught the world a lesson in courage and resilience. When the regime lost control of Ghouta its people built new forms of local governance and held free elections for the first time in Syria’s history. When the bombs started falling on neighbourhoods its teachers and doctors took schools and hospitals underground and ordinary residents put on white helmets and rushed to rescue their friends and neighbours. The people of Ghouta launched inspiring civil society projects, often women-led. They created new media platforms and produced award-winning photojournalism. They created alternative energy resources and introduced new farming techniques.

But after this latest, relentless onslaught, people were truly left with no choice. If they remained in Ghouta they risked being detained and tortured as the Syrian regime closed in, particularly the ones who decided to teach, treat the wounded, or post updates to Facebook. So now many are leaving behind everything they’ve ever known to go to a place that isn’t that much safer. The province of Idlib, home to more than two million, is also being struck from the air by the Syrian regime and its Russian ally.

If only the ‘international community’ had been even half the community created by these brave men and women.

To be continued

An excellent new edition of Middle East Report (290) on The New Landscape of Intervention; full download details here.

An excellent new edition of Middle East Report (290) on The New Landscape of Intervention; full download details here.