This is the third in a series of posts on siege warfare and East Ghouta (Damascus); the first is here and the second here. It’s also an extension to my post on the chemical weapons attacks on Douma here.

Slow violence and siege warfare

In an earlier essay in this series I described the slow violence intrinsic to siege warfare: the malnutrition and misery set in train once food becomes a weapon.

But there is another slow violence inscribed into the calculus of siege warfare: the subjection of the trapped population to multiple forms of military and paramilitary violence from which there is little or no escape. I’ve written about the slow violence of bombing – the dread anticipation of the next strike, even when death from the skies has become normalized, and the long drawn-out aftermath: the search for survivors in the rubble, the rescue and often prolonged treatment of casualties, the salvage, clearance and rehousing operations, and the enduring grief and traumatic flashbacks of the survivors.

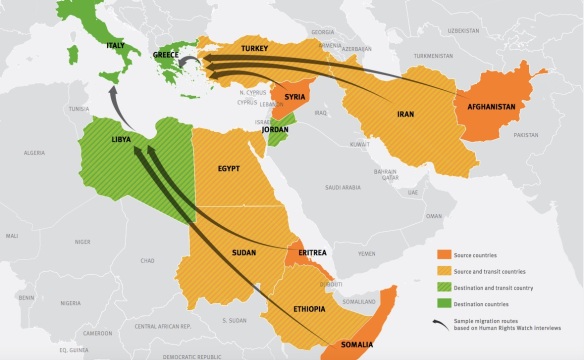

All of this was multiplied in East Ghouta, which was under siege by the Syrian Arab Army and its proxies and allies from the winter of 2012 until the spring of 2018 (‘April is the cruellest month…’). The parameters of this slow violence were exacerbated and extended in multiple ways: by the systematic targeting of hospitals and clinics and the withholding of medical supplies; by the forcible displacement of those who surrendered to a series of what critics have described as elaborately constructed killboxes elsewhere in Syria, where the violence will surely follow them; by the confiscation of their homes and property under new ‘absentee’ laws; and for those who chose to remain, by the abuses, humiliations and assaults (and for some, detentions) involved in the regime’s ‘reconciliation agreements’ and screening and resettlement operations.

Here I focus on direct military and paramilitary violence; in the next post in the series I’ll deal with medical care under fire, and in the final post I’ll address the bruising aftermath: the displacements, property confiscations, resettlements and more.

It’s important to remember throughout my discussion that the two modalities of siege warfare – the denial of food, other resources and medical supplies and the direct violence of air and ground attack – worked like scissors. Sometimes one was dominant, sometimes the other, and sometimes they cut into the lives of the besieged population together. But they have always depended on each other: interdicting movement across the siege lines required military and paramilitary cordons, while military and paramilitary offensives were predicated on degrading the ordnance and resources of the armed groups and weakening the resolve of the besieged population. It’s also necessary to recognise that direct violence has been inflicted on the people of the Ghouta not only from outside – by aircraft, helicopters and artillery, and eventually by ground assault – but also from inside through the summary executions, detentions and repressions carried out by the armed opposition and the infighting between its different constituencies.

In the early stages of the siege the situation was fluid. There were times when the armed opposition groups beat back the Syrian Arab Army and its supporting militias and advanced deeper into Damascus; at others they were forced to retreat to their bases in the Ghouta from where they continued to launch guerrilla raids and mortar attacks on the capital and its perimeter. In the course of the war, pro-government forces launched three major offensives that successively transformed the terms of military engagement with East Ghouta and I’ll consider them in turn.

Offensive I: Operation Capital Shield

In the early months of 2013 pro-government forces stormed several towns to the south of Damascus, and there were allegations that chemical weapons had been used in the course of capturing al-Otaybeh on the southern fringe of East Ghouta in March and April (and at least two other districts outside the Ghouta). The loss of al-Otaybeh was a major blow to the rebels – it cut a major supply line from the south – and by June 2013 it was clear that pro-government forces were moving to secure the perimeter of the capital, supported by Iranian troops and militias and by Hezbollah fighters. Precisely because the situation was so fluid it’s impossible to be definitive, and the sources are fragmentary and open to competing interpretations; here is how the Institute for the Study of War summarised the state of play on 9 August 2013:

This preliminary report was written by Elizabeth O’Bagy – who may well have exaggerated the reach of the rebels (for an alternative reading of the situation on the ground see here) – but her analysis was subsequently supported by a detailed security report written for ISW by Valerie Szybala. Their combined narrative suggests that rebel forces had launched a major co-ordinated counter-offensive on 24 July 2013 from Irbeen, Zamalka and Ain Tarma in the Ghouta, pushing across the M5 highway into Jobar, al-Qaboun and Barzeh, and then using those neighbourhoods as springboards to launch attacks on pro-government forces designed to bring them within striking distance of central Damascus:

[The first map is from the ISW security report, the second from information supplied by reporter Mohammed Salaheddine and used by Hisham Ashkar here].

There were also reports that rebel groups had captured an ammunition depot and had used radar-guided surface-to-air missiles to bring down a Syrian Arab Army helicopter and two fighter jets. Emboldened, the rebels warned the government that any of its aircraft flying over East Ghouta would be shot down. This was no doubt bravado, but these threats were straws in the wind to a regime building a bigger haystack. Szybala argues that rebel advances and their use of increasingly sophisticated weapons systems, combined with a mortar attack on Assad’s convoy on 8 August (probably from Jobar) and the heightened fear of increased international support for opposition groups like the Free Syrian Army, meant that the regime ‘felt increasingly threatened in Damascus and believed itself to be at unprecedented risk.’

On 21 August 2013 the Syrian military launched Operation Capital Shield focused on West and East Ghouta, ‘their largest-ever Damascus offensive, aimed at decisively ending the deadlock in key contested terrain around the city.’

At 0245 reports began to flood in about a chemical weapons attack on Ain Tarma and Zamalka in East Ghouta; these were followed by reports of a third attack on Moaddamiya in West Ghouta at 0500 (see map above). Dexter Filkins spoke with Mohammed Salaheddine by telephone soon afterwards:

When Salaheddine arrived [in East Ghouta], he saw four big pits, where trucks were carrying bodies of the dead. He estimated that he saw about four hundred corpses. Salaheddine said that he went to the central hospital in a town called Zamalka, where, he told me, there were so many Syrians suffering symptoms of poison gas that the doctors could not treat them all.

“There were so many people I could not count them,’’ Salaheddine said of the hospital. Many of the people, he said, were weak and couldn’t breathe; the doctors were trying to give injections of atropine, an antidote, to as many of the victims as they could, and administer oxygen to others. “People were unable to breathe,’’ Salaheddine said. “They were asphyxiating. The doctors had really limited resources. We were trying to help, but we didn’t have enough.

“People were panicking,” he went on. “They were saying, Am I dead or am I alive?”

The worst moment, Salaheddine said, came when he found three women huddled together in the hospital; a young woman, her mother, and her grandmother. All were suffering the symptoms of poison gas, he said, and each was trying to comfort the others. “I was trying to rescue the grandmother,” Salaheddine said. “She was dying. I was trying to give her oxygen. She kept saying to me, ‘My son—my heart, my heart.’ She was gasping for air. She was in agony. She died in my arms.”

And here is a doctor who helped to treat the casualties:

I was sleeping in the doctor’s house in one of the basements beside the operati[ng] room. At about 2:30 am, we got a call from the central ER. The physicians who were on staff that night informed me that it was a chemical attack. I arrived and in the next 10 minutes, it was like a nightmare. One of the medics entered and said gas had fallen in Zamalka and all the people died. Then I realized that it was a huge chemical attack. All of the hospitals from Zamalka to Douma were filled. I asked some people to go to the mosque and use the speakers to request that everyone who had a car go to Zamalka and help. I don’t know if it was a wise decision or not. But there were so many heroes that night. Our local culture says that we would die to save others.

The numbers became over all capacity. I asked to our staff to do medical work in two schools and mosques, where there are water tanks. If there is no water, you don’t have a hospital. There was just one person who could classify the patients— me. I was the only one who studied it. I had to decide quick response for bad cases and delay medium and moderate cases. After 30 minutes, there were hundreds. We didn’t realize how many, but we knew there were hundreds.

I put two medics on the door of the ER. I said that every patient who is unconscious or shaking, take him down to the ER. All kids or seniors, or anyone shouting loudly, put him in the second ER. All others should go in the third medical point. We could not do anything in the second or third medical points—we could not provide them with any medicine. From the first hour, I gave all staff their mission so that they know what to do. I told them not to ask, just to give atropine to all…

After 90 minutes, one of my medical staff fell down. The symptoms began to appear on medical staff themselves, and we had to change our strategy. I chose to see the patients one by one, and check vital signs to see if there was a misunderstanding. I spent 5 seconds for every patient, and did not do any medical procedures myself – I just made decisions. The staff did a great job here.

At 11 am, the bombs and shelling began… I called my friend Majed and he was crying as we prepared the first report for media. The number in Douma was 630 patients and 65 victims. We could realize some symptoms we never saw before.

The Syrian-American Medical Society estimated that more than 1,300 people were killed in the attacks – 97 per cent of them civilians – and 10,000 others were affected. Their symptoms, described by eyewitnesses and confirmed by multiple videos and digital images, were consistent with exposure to a nerve-agent. A month later hundreds still suffered from respiratory problems, nausea, weakness and blurred vision that were sufficiently serious to require medical attention (though this was compromised by the continued siege and the consequent difficulty of obtaining medical supplies, including oxygen).

Other sources provided other casualty figures, but that’s not surprising. As Human Rights Watch explained in its analysis,

Because the August 21 attacks took place in two separate areas of Ghouta, and owing to the chaos resulting from the large number of casualties, it is difficult to establish a precise death toll. The areas affected do not have any large hospitals, and rely on several small, badly supplied underground clinics to provide medical assistance. According to the doctors interviewed by Human Rights Watch, these small medical clinics were overwhelmed by the number of victims, and many of the dead were never brought to the clinics and thus not registered. According to Médecins Sans Frontières, at least 3,600 persons were treated for symptoms consistent with exposure to neurotoxic agents at three hospitals it supports in the area in the first three hours following the attacks.

Whatever the numbers, these were clearly mass-casualty events: and for that very reason, the victims too often remained not only faceless but nameless. That same month (August 2013) Hisham Ashkar provided an important corrective to the de-humanising anonymity of the statistical shrouds (and the photographic record):

(The original photograph was taken at al-Ihsan Hospital in Hammouriya; the victims all had numbers fixed to their foreheads).

This was vital work, but even the anonymity of the victims was eclipsed by the almost immediate desire to identify those responsible for the attacks. This too is exceptionally important, but Hisham is right to remind us of what is lost in all the maps and calculations of missile trajectories.

A team of UN weapons inspectors led by Professor Ake Sellström was already in Damascus to investigate previous allegations of chemical weapons use, and after several days (and an attack by unidentified snipers) the investigators were allowed to visit the three Ghouta sites during a temporary ceasefire, where they took samples and interviewed 36 survivors (with ‘severe clinical presentations’ since they would have had ‘significant exposure to the chemical agent’) along with doctors, first responders and other witnesses. Their report was delivered on 13 September and concluded that ‘the environmental, chemical and medical samples we have collected provide clear and convincing evidence that surface-to-surface rockets containing the nerve agent sarin’ had been used in the attacks.

The authors were not permitted to assign responsibility, but two dossiers published before the UN investigation delivered its report to the Secretary-General claimed to have identified the likely culprits. On 30 August the Obama administration published an unclassified summary of what it called a ‘government assessment’ based on multiple streams of intelligence (‘human, signals, and geospatial intelligence’) as well as open source reporting. It concluded ‘with high confidence’ that the Syrian government was responsible for the attacks. Intercepts revealed preparations for the attacks three days before they were launched, and satellites had identified ‘rocket launches from regime-controlled territory early in the morning, approximately 90 minutes before the first report of a chemical attack appeared in social media.’ The assessment linked the attacks to Operation Capital Shield:

The Syrian regime has initiated an effort to rid the Damascus suburbs of opposition forces using the area as a base to stage attacks against regime targets in the capital. The regime has failed to clear dozens of Damascus neighborhoods of opposition elements, including neighborhoods targeted on August 21, despite employing nearly all of its conventional weapons systems. We assess that the regime’s frustration with its inability to secure large portions of Damascus may have contributed to its decision to use chemical weapons on August 21…

On the afternoon of August 21, we have intelligence that Syrian chemical weapons personnel were directed to cease operations. At the same time, the regime intensified the artillery barrage targeting many of the neighborhoods where chemical attacks occurred. In the 24 hour period after the attack, we detected indications of artillery and rocket fire at a rate approximately four times higher than the ten preceding days.

This was a rapid response and the accompanying map of areas affected by the attacks turned out to be inaccurate: as a note on the map conceded:

Reports of chemical attacks originating from some locations may reflect the movement of patients exposed in one neighborhood to field hospitals and medical facilities in the surrounding area. They may also reflect confusion and panic triggered by the ongoing artillery and rocket barrage, and reports of chemical use in other neighborhoods.

For critics this was far from the only inaccuracy, but on 10 September, just three days before the UN investigation delivered its report, Human Rights Watch also concluded that the evidence its analysts had examined ‘strongly suggests that the August 21 chemical weapon attacks on Eastern and Western Ghouta were carried out by government forces.’

They based their preliminary conclusions on the large scale of the attacks, the Syrian military’s documented possession of the types of rocket retrieved from the affected sites, and the state’s ability to prepare or obtain and deliver nerve-agents in sufficient quantity.

Once the UN report had been published, HRW used the detailed specifications of the rockets tabulated in an appendix to calculate possible trajectories:

The two attack locations are located 16 kilometers apart, but when mapping these trajectories, the presumed flight paths of the rockets converge on a well-known military base of the Republican Guard 104th Brigade, situated only a few kilometers north of downtown Damascus and within firing range of the neighborhoods attacked by chemical weapons.

According to declassified reference guides, the 140mm artillery rocket used on impact site number 1 (Moadamiya) has a minimum range of 3.8 kilometers and a maximum range of 9.8 kilometers. The Republican Guard 104th Brigade is approximately 9.5 km from the base. While we don’t know the firing range for the 330mm rocket that hit impact site number 4, the area is only 9.6km away from the base, well within range of most rocket systems.

HRW conceded that its results were not conclusive, but the balance of probabilities from these dossiers was used by many commentators to indict the Assad regime. Similarly, on 17 September the New York Times tracked the co-ordinates of the rocket trajectories given in the UN report and concluded that they pointed back to ‘the center of gravity of the regime’ on Mount Qasioun.

The geometry of culpability was complicated by other assessments – I am leaving on one (far) side the vindictive delusions of a distant nun (who, among other lunacies, demanded to know where all the victims shown in the photographs and videos had come from since the Ghouta was ’empty’, ‘a ghost town’, and insisted that the dead and injured were ‘women and child abductees’; and also the anonymously sourced speculations of Seymour Hersh that Turkey had supplied Jabhat al-Nusra with the sarin to carry out an attack that would draw the United States across Obama’s ‘red line’ to intervene directly in the conflict (for critical comments, see here and here) – to focus on the calculations made by Richard Lloyd and Professor Theodore Postol (which also reappear in the debate surrounding Hersh’s conjectures: see here). They claimed that the munitions used in the attacks were ‘improvised’ and that, when the aerodynamic drag exerted on the rockets by their heavy payload is factored in, their range contracts to around 2 km. Superimposing the new radii on the map previously published by the Obama administration identified launch locations far from ‘the center of gravity’ of the regime:

Accordingly Lloyd and Postol concluded that the US government assessments had to have been based on faulty intelligence and that they were almost certainly wrong. That may well be so, but it does not follow that these new geometries reassign culpability to the opposition. The large volume of sarin factored in to the heavy payload of the rockets makes the involvement of a state actor far more likely than a non-state actor (see Dan Kaszeta‘s analysis here) and the ring around East Ghouta that appears on the revised map follows the cordon lines through which the siege was being so actively contested in the days and weeks before the attacks: a situation plotted inaccurately on the assessment map in both its versions but shown on Hisham Ashkar‘s map I reproduced earlier (see Eliot Higgins‘s analysis here and also here). In short, the reduced range does not militate against the use of mobile rocket-launchers from territory held by pro-government forces (however precariously).

I’m not the person to adjudicate between these competing views, though I do believe that the weight of evidence makes it far more likely that the Assad regime carried out the attacks than any opposition group. Instead I want to emphasise two other conclusions.

First, these chemical weapons attacks were designed to inflict maximum possible harm on civilians. Those are not my words; they come from Theodor Postol himself:

-

This attack was designed to cause the maximum possible harm to civilians with the technology that was available to the attacker.

-

The attack was executed at a time of day that would maximize the density of nerve agent near the ground where the civilians reside.

-

The pancake geometry of spreading nerve agent at that time of day greatly increased the area on the ground, causing the maximum number of people possible to be exposed to an organophosphorous nerve agent.

-

If soldiers with proper equipment had been attacked in this manner, casualties would have almost certainly been very low.

Second, the result of Operation Capital Shield was a stalemate, and it is clear that civilians in the Ghouta continued to be caught between the overwhelming fire power of the Assad regime and its allies and the brutalities of the armed opposition. As Linah Alsaafin explained eighteen months later:

The residents of Eastern Ghouta [are] trapped between a rock and a hard place, facing down constant shelling by Syrian government forces on the one hand, while on the other living through the ongoing rebel struggle for control.

“People are tired from all the factions,” [Nuran al-]Na’ib said. “They don’t care so much about the protests and who is in power. Their only concern is to find food for themselves and their families.”

Abu Ahmad agreed: “Most people in Ghouta do not want Assad to stay in power, but at the same time there is a high number of complaints against the course the revolution has taken. There is no love lost for Jaysh al-Islam. The ethical superiority we witnessed at the beginning of the protests … has all degenerated in the face of the crimes these armed groups are committing against civilians in Damascus and elsewhere.

A rock and a hard place

The background throb of daily violence continued as the front lines were consolidated in the wake of the initial offensive and response. In January and February 2014 uneasy truces were negotiated with armed groups in al-Qaboun and Barzeh that allowed the continuation of crucial, quasi-clandestine supply lines into East Ghouta (see my extended discussion here). The stalemate materially assisted the Assad regime by opening time-space windows of opportunity for pro-government forces, which had been weakened by defections and casualties from opposition offensives, and enabled a renewed focus on the besieged cities of Homs and Aleppo.

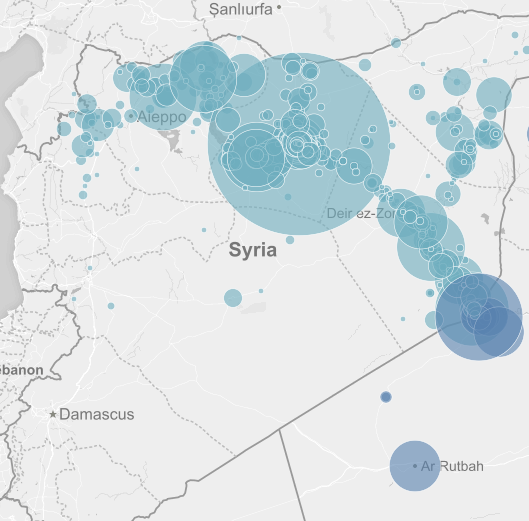

During those two northern campaigns air and artillery strikes on the Ghouta were not suspended. Syrian forces had deployed cluster munitions and ‘parachute bombs’ against the towns of the Ghouta since 2013, and they continued to use them without regard for the civilian population. Both weapons are notoriously indiscriminate; the former disperse clusters of bomblets over a wide area to detonate on contact, thus delivering ‘maximum destruction with minimum accuracy’, while the slow descent of the unguided fuel-air bomb by parachute is terminated by an explosion metres above its impact site that releases an aerosol cloud which ignites to destroy everything within a 25 metre radius. In those years the use of equally indiscriminate ‘barrel bombs’ – aerial IEDs – dropped by Syrian helicopters was more common in Aleppo, but their use became more widespread against the Ghouta from the summer of 2015. Amnesty International, citing the Violations Documentation Center, reported:

Syrian government air strikes killed 2,826 civilians in Damascus suburbs between 14 January 2012 and 28 June 2015. Of these, according to the VDC, more than half – 1,740 civilians – were killed in Eastern Ghouta. In the same period, according to the VDC, Syrian government air strikes killed 63 anti-government fighters in Eastern Ghouta, indicating the indiscriminate and disproportionate nature of government air attacks on the area.

There are few eyewitness reports during this period, but Amnesty investigated ten air strikes in detail that took place between December 2014 and March 2015. Here is one student describing the aftermath of an attack by a parachute bomb on Douma on 5 February 2015:

Usually the Syrian government does not start its aerial attacks before 10am or 11am. On that day the strike was carried out at 8.20am. I woke up to the sound of the fighter jet. I looked out and saw the MiG. I heard explosions a few seconds later. I was 200 metres away from the strike. I arrived at the site after five minutes. When I arrived I saw the site had been hit four times 50 metres apart. One of the bombs totally destroyed a residential building and damaged the buildings around it. Residents told me that they had seen a rocket strapped to a parachute but they had not had time to run.

The targeted residential buildings are located next to Taha mosque in Khorshid neighbourhood [see image above]. It was a bloody morning. Injured people were scattered everywhere… I don’t remember the exact number of bodies but I saw at least 10 bodies on the street. I saw other bodies but I don’t know if they were alive or dead. I also saw old people among the injured.

Over the same period the region also came under artillery fire from Syrian batteries launching missiles and rockets from Mount Qassioun and from other ground forces firing mortars from positions much closer to the front lines.

The situation worsened over the summer, and August was one of the bloodiest months of all. Hospitals in East Ghouta supported by Médecins Sans Frontières treated at least 150 cases of violence-related trauma per day between 12 and 31 August 2015:

“This is one of the bloodiest months since the horrific chemical weapons attack in August 2013,” said Dr. Bart Janssens, MSF director of operations. “The hospitals we support are makeshift structures, where getting medicine is a dangerous and challenging endeavor, and it is unthinkable that they would have been able to cope with such intense emergency traumas under such constraints. The Syrian doctors’ continued unswerving effort to save lives in these circumstances is deeply inspiring, but the situation that has led to this is totally outrageous.”

The data for the mass casualty influxes at six of the 13 MSF-supported hospitals in East Ghouta reveal 377 deaths and 1,932 wounded patients in August. Among them, 104 of the dead and 546 of the wounded were children younger than 15. The intensity of the bombings temporarily cut some communication channels, but based on initial reports from other MSF-supported facilities, it is clear that at least 150 war-wounded patients were treated per day from August 12 to 31.

The misery of the civilian population was heightened by simmering tensions between the armed opposition groups, which erupted into open conflict at the end of April 2016 when around 300 people were killed in fighting between Jaish al-Islam (JAI) and a Free Syrian Army group Failaq al-Rahman. The fighting became so intense that nearby clinics and pharmacies could only open for an hour or so each day; some of them were attacked and looted. According to the same report, the bloody climax was reached

when Jaish al-Islam stormed and took control of the towns of Misraba and Mudira, both held by Failaq al-Rahman, using tanks. The attack prompted Failaq al-Rahman to accuse JAI of “leading East Ghouta into a sea of blood.”

When a deal was reached to end hostilities several days later Misraba was declared a ‘neutral area’ and both JAI and Failaq al-Rahman agreed to withdraw. But by the end of July residents protested that their town was still a military zone ‘surrounded by earthen berms and security checkpoints’ and demanded that all armed groups leave along with their ‘heavy weaponry’. A group of brave women led a demonstration against the continued (para)militarization of the town – according to Syria Direct men did not join ‘because they were afraid of being arrested, beaten or shot’ – and the local (civilian) council backed their demands:

We left Bashar al-Assad for freedom and dignity. It doesn’t make sense for another group to come along and revoke our freedom.

Those last three words are freighted with meaning; the men had good reason to fear detention. JAI had previously paraded regime prisoners taken during skirmishes on the front lines through the streets and placed some of them in cages on rooftops as human shields against air strikes (see here and here, and the statement by Human Rights Watch here), but its cruelty extended to opponents of the regime who failed to support or submit to its own authority too.

One young man who survived incarceration in JAI’s notorious al-Tawba (‘Repentance’) prison in Douma (above, after JAI’s withdrawal) described what happened to Syria Deeply:

The young man said he was interrogated and tortured by being electrocuted and beaten with metal wires while hanging from a wall. “I was detained at the regime’s air force security prison once, and I found no difference between the two, except that Jaish al-Islam claims to be part of a revolution,” he said.

“I was determined that no matter what they did, I would never admit to something I had not done. I believe my stubbornness frustrated them, so they started a new cycle of torture – they starved me.”

After two months of torture, Saeed was transferred to another cell, where he spent another six months. He was never brought before a judge nor allowed to have any visitors.

He recalled: “[Six months later] they finally called me to the interrogation room again. There, one of them said to me, ‘This was a lesson, so that you learn not to criticize Jaish al-Islam’s leaders. If you do it again, your punishment will be serious.’”

At least one commentary claims there was a difference between the prisons that formed part of the criminal justice system introduced by the armed opposition groups and these nominally secret jails for political prisoners, but in practice the distinction did not always amount to much. In August 2016 two young brothers, desperate for food, stole a pair of shoes from outside a mosque during prayers; their plan was to sell them for bread, but they were caught by JAI and tried in its regular court. The older boy – like many other ‘ordinary’ criminals – was sentenced to one month’s hard labour, which involved cementing and transporting dirt as part of ongoing tunnel construction. The younger was imprisoned in an underground cell at al-Tawba with adult prisoners for a month; he was just ten years old (details here). Arbitrary arrests were also common; in another report Syria Deeply interviewed one man who was imprisoned in al-Tawba over a mundane dispute with a neighbour who, unfortunately for him, had high-level connections with JAI. He was inside for a month and tortured.

These violations and abuses mirrored the still greater excesses that were the lifeblood of the regime’s vastly more extensive carceral archipelago – see for example Amnesty International‘s report on Saydnaya Prison (which it describes as a ‘human slaughterhouse’) here and here and its collaboration with Forensic Architecture here and here – but when besieged Ghouta was so often described as a giant prison many of those trapped inside were understandably sickened to discover that their jailers were not only on the outside.

Meanwhile, the Syrian Arab Army supported by Hezbollah had capitalised on the internal fighting to break through the front lines to the south in May and capture the Marj, an agricultural landscape of farms, small towns and villages that had served as the Ghouta’s breadbasket throughout the siege. JAI had supposedly withdrawn 800 of its fighters from the district a few days before, leaving other ‘rebels scrambling to fill the void‘, but JAI protested that it had been forced to do so because Jabhat al-Nusra (an ally of Failaq al-Rahman) had blocked the road to the Marj and prevented the evacuation of wounded and the resupply of its fighters.

The loss of al-Marj was a body blow to the Ghouta’s siege economy, exacerbating the immiseration of the population, and the recriminations that followed did little to assuage tensions between the armed opposition groups.

These spilled over into open violence again less than a year later. At the end of April 2017 Aron Lund reported renewed clashes between Jaish al-Islam and Failaq al-Rahman and allied rebel groups. In the first five days of fighting more than 95 people were killed and hundreds wounded. In short order Médecins Sans Frontières was forced to suspend medical support to East Ghouta when armed men stormed one of its hospitals ‘to seek out specific wounded patients’ belonging to an opposing faction – in direct violation of the medical neutrality required by international humanitarian law – and could not safely restore its provision until June. There were dozens of peaceful public demonstrations calling for an end to the in-fighting, but in response to one such protest in Irbin some of JAI’s fighters opened fire on the crowd and wounded 13 people:

This was a grim realisation of the fears of would-be demonstrators the year before, and another dismal echo of the regime and the response of its security forces to peaceful demonstrations in 2011 that did so much to spark the civil war in the first place. It’s as unsurprising as it is regrettable that the office of the Violations Documentation Center in Douma should have been raided by a mob from the ‘Popular Movement’ of JAI in August, which stole equipment and attacked the staff, and that JAI’s local police should have done nothing to protect the building or its occupants.

These roiling divisions within the armed opposition combined with the regime’s pyrrhic victories over Homs (whose siege ended in May 2014) and Aleppo (whose recapture was completed by December 2016) to allow two renewed offensives that affected East Ghouta. Both government campaigns were considerably strengthened by direct support from Russian armed forces (which had started in September 2015).

Offensive II: al-Qaboun, Barzeh and the violence of ‘de-escalation’

On 18 February 2017 pro-government forces abandoned the truce and attacked al-Qaboun and Barzeh without warning and with extraordinary ferocity. One of the defining dimensions of siege warfare is that its victims have precious few escape routes from its indirect or direct violence. Here is one resident from al-Qaboun speaking to Syria Direct:

“The bombardment came out of nowhere,” [Abu Ahmad] al-Halabi … told Syria Direct on Sunday morning. “We were working, living our daily lives. We didn’t sense anything until the rockets began to fall.”

Al-Halabi says that he and his seven children tried to flee their neighborhood after the shelling began on Saturday, but they were prevented from passing through regime checkpoints and leaving the area.

Many people fled through the tunnels, seeking sanctuary in East Ghouta. By the end of March the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimated that more than 17,000 people had fled into the Ghouta, and that the situation for the 25 – 30,000 who remained in al-Qaboun and Barzeh was increasingly precarious. The neighbourhoods were in ruins, barely recognisable, and still the bombing and shelling continued.

The ground and air offensive reached its peak during May – the image above shows pro-government forces in al-Qaboun – and surrender agreements were rapidly concluded. Convoys of buses started the process of forcible transfer of fighters and civilians to Idlib; the Free Syrian Army had already described the campaign as a ‘systematic strategy of ethnic cleansing’. Some people remained in Barzeh, but if the wretched cleric to whom I referred earlier really wanted to see a ‘ghost town’ she should have looked outside the Ghouta and after the Assad regime’s assault on al-Qaboun. Siege Watch reported:

After the final buses left Qaboun, leaving the neighborhood depopulated, photos emerged of what appeared to be rampant looting and vandalism by pro-government forces and the burning of remaining property. The looted property was sold in the government-controlled Mezze 86 neighborhood in so-called “Sunni Markets.”

By then pro-government forces had breached all the tunnels, and the siege of the Ghouta was absolute (more here). Those who had escaped into East Ghouta soon found they had been forced from the frying pan into the fire, and now – like thousands of residents in the Ghouta – they faced multiple displacements. For these attacks prepared the ground for the third and final offensive, the endgame that was played out during the winter of 2018.

Yet in May 2017, as the attacks on Barzeh and al-Qaboun escalated, East Ghouta was recognised as one of four ‘de-escalation zones‘ through an agreement between Russia, Turkey and Iran (al-Qaboun, which was described by the Russian Foreign Ministry as ‘controlled by insurgents of Jabhat al-Nusra’ [reconstituted as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)], was explicitly excluded from the agreement). The Ministry’s briefing was a surreal affair, conjuring up a world in which there was no siege at all: ‘In the morning, most civilians leave Eastern Ghouta for Damascus for earning money, and, in the evening, they come back.’

The officer providing these fanciful details, Colonel General Sergei Rudskoy (the first Deputy Chief of the Russian General Staff) acknowledged that the enclave was far from being a ghost town: ‘About 690,000 civilians live in Eastern Ghouta.’ The estimate was roughly twice that of the UN and most NGOs, but the recognition that the Ghouta was overwhelmingly inhabited by civilians (‘about 9,000 insurgents are controlling it’) should be remembered in the light of what followed.

Failaq al-Rahman accepted the terms of the de-escalation agreement in August 2017 but, like Jabhat al-Nusra/Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, JAI was explicitly excluded from the provisional truce and was regarded as a legitimate target by pro-government forces. This did nothing to de-fuse tensions between the armed opposition groups, but in any case the agreement was moot. The slow violence of the siege accelerated and within months the military offensive had started to gear up too. In mid-November Failaq al-Rahman and its allies were accused of attacking the Military Vehicles Administration base near Harasta, a key government strongpoint, and in response both shelling (including ground-launched cluster munitions) and air strikes intensified; by early December the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimated that 200 civilians had been killed in East Ghouta by these attacks. De-escalation had only existed on paper and it was evidently now a dead letter. Human Rights Watch claimed that a number of the attacks were indiscriminate and so were also violations of international law – war crimes – but its protestations were ignored.

The bombing, the shelling and the killing continued, and by January residents were reported to be ‘moving from town to town with little more than the clothes on their backs to escape an amorphous frontline.’ Some found lodging (but rarely shelter) with family and friends; the more fortunate might be able to rent rooms, but these were often on the upper floors of buildings so that their fortune was short-lived: these were highly vulnerable to an air strike, and many people were already moving down to the basements.

Offensive III: The endgame

The endgame started with a cataclysmic storm of aerial violence on 18 February 2018. Abudlmonam Eassa, a local photographer, kept a diary of the first days of the assault. ‘A strike hits very close today,’ he wrote on 19 February (a day when 19 air strikes killed at least 127 people):

The whole area seems to have been burned. During the first few seconds, you think no one is dead, you just see ashes and destruction. That’s because people hide as soon as they hear the sound of a rocket or a plane.

Two days later, scorched earth and rubble as far as his eyes could see:

I climb to the rooftop to get a better view. Everything is burning. It seems like everywhere was shelled – Saqba, Misraba, Douma, Kafr Batna… it seems like the whole area is burning.

By the end of the week:

People are cowering in shelters. Everyone is in shock. We can’t understand anything. Everything is out of service. I can’t believe the difference four days of bombardment has made. The whole area has been changed, erased. The streets aren’t there anymore. They’re full of dust, rubble.

A broken landscape of flames and ash, dust and rubble: and already the Syrian government was claiming there were ‘few civilians left in eastern Ghouta‘. The UN and most NGOs estimated there were at least 350,000 of them still trapped in the enclave. Many, perhaps most, were in basements, shelters and tunnels, too scared to leave even to search for food in many cases: ‘just a cup of water or a piece of bread may cost a man his life.’ ‘It’s not a war, it’s a massacre,’ exclaimed one exhausted local medic. An official with UOSSM [an international coalition of humanitarian and medical NGOs] described the bombardment as ‘hysterical’ – ‘a humanitarian catastrophe … the mass killing of people who do not have the most basic tenets of life’ – while the Russian ambassador to the United Nations presented his own diagnosis of hysteria, airily dismissing accounts of civilian casualties as ‘mass psychosis’ and images of terrified families huddling in makeshift shelters as merely ‘propagandistic scenarios of catastrophe.’ Rejecting calls for a ceasefire, he continued:

You get the impression that all of eastern Ghouta consists only of hospitals and it is with them that the Syrian Army is fighting… This is a well known method of information warfare.

In fact hospitals were key targets – 13 of them were hit in the first 48 hours alone, four of them destroyed completely – and the same doctor claimed that aircraft were circling overhead and following ambulances (there were never enough of them) to locate clinics and medical centres.

That might seem fanciful given the speed at which fighter jets streak across the sky, but Syrian Arab Army helicopters laden with barrel bombs were perfectly capable of executing such a manoeuvre. In addition, many different drones were in operation above the Ghouta. These ranged from small commercial drones used by the Syrian Arab Army (see below; also here) to much larger Russian and Iranian drones, all of them relaying real-time video to facilitate targeting from other platforms and some of them (like the Shahed-129) carrying their own weapons. A senior officer explained that the drones ensured the Army ‘was well aware of all the fortifications, defenses, warehouses and logistics routes’ and established ‘coordination between command and the advancing forces.’ Targeting was directed at more than those military objectives. Humam Husari, a Douma film-maker, explained: ‘Usually people could move a little bit at night and sometimes during the day, but now because of the drones they capture any movement and will be targeted immediately.’

Precision intelligence doesn’t count for very much without precision weapons, and there were persistent reports that both Russian and Syrian aircraft were using unguided ‘dumb’ bombs. Subsequently Robert Fisk seemed to confirm the indiscriminate nature of the bombardment:

[T]his from a Russian source – outside Syria, but all too familiar with Russian military operations inside the country – who knows about the trajectory of rockets: “The bombs we used in Ghouta were not “smart” bombs with full computer guidance. Maybe some. But most had a variable of 50 metres off target.” In other words, you can forget the old claim of “pin-point” accuracy… These Russian bombs launched against eastern Ghouta had a spread pattern of 150 feet each side of what the pilots were aiming at; which means a house instead of an anti-aircraft gun. Or one house rather than another house. And anyone inside.

I say ‘seemed’ to confirm, because in the same report Fisk added this bizarre rider:

There are streets in Ghouta, incredibly enough, whose buildings are still standing relatively unscathed. They were spared during the bombardment because their inhabitants said – by mobile phone – they wanted to stay in their homes and would not resist the Syrian army.

So all those inaccurate, unguided bombs that could not distinguish between ‘one house rather than another house’ were nevertheless able to distinguish between the location of one cellphone and another? I doubt it (and I’ve seen no other reference to those phone calls). Other observers noted that Syrian pilots were not trained in the use of smart weapons – which were far more expensive – and suggested that Russian pilots followed suit either to make attribution more difficult or simply as ‘a tactic aimed at scaring civilians.’ That rings true; the most common way to compensate for a lack of precision is through volume – hitting the target area with multiple strikes – which, in the Second World War, was sometimes called ‘terror bombing’. Targets in East Ghouta came under fire from aircraft and from artillery.

In consequence:

“We stopped comprehending where the bombing is coming from, either from the sky or the ground,” Khalid Abulwafa, an ambulance driver and member of the Syrian Civil Defence, told Al Jazeera. “We arrive at a site that has been hit, and immediately another attack follows… we just run to pull out as many people as possible before it’s too late,” he said. “Multiple raids hit different areas at the same exact time… we don’t have the ability to rush to all the areas at once.”

Another doctor told the Syrian-American Medical Society:

Hospitals are overwhelmed. Floors are overflowing with injured and blood. Those patients we discharged a couple of days ago are now back with more serious injuries.

In the first six weeks of the year, before the onslaught began, hospitals and clinics supported by Médecins Sans Frontières had recorded 180 dead and more than 1,600 wounded (up to 18 February); in the next three days alone a further 237 dead and 1,285 wounded were reported, ‘extraordinary mass-casualty influxes’, and this was only a partial accounting.

It was as difficult and dangerous to attend to the dead as it was to the injured. According to one report on 21 February:

Pathologists and gravediggers in the [Ghouta] said before the violence accelerated that they had 20 to 50 graves on standby at any given time. This week, they said that was not enough. “We are overwhelmed. We are throwing body parts in mass graves. It’s all we can do,” said one man.

The next day one grieving relative confirmed the enormity of what was taking place:

Abdullah was desperate to bury his uncle quickly in line with Muslim practice. He spent an hour retrieving the corpse from the bombed wreckage of the family home. But for a day he could not lay it to rest. By daylight, the constant Syrian regime air strikes were too heavy to risk going out. By night, he feared the graveyard would be deadly. “If they [the regime] caught any light or movement, we could be immediately targeted,” says Abdullah, his voice trembling. “I don’t think the situation can be worse — there is no ‘worse’ left.” Abdullah, who asked not to be identified by his full name, entrusted the body to the undertakers, to be buried in darkness with no loved ones nor final rites.

The aerial assault deployed the full arsenal of the Syrian military and its allies, including barrel bombs, cluster munitions, ‘elephant’ rockets and missiles; there were also reports of chlorine gas.

A young mother, Nivin Hotary, kept a diary of those desperate weeks confined to a basement (see also here) and like a prisoner – ‘detained in this prison, under house arrest’ – marked the days of her incarceration on the wall (above). Here is part of her entry for 22 February:

Detained… we know that our crime is that we called for freedom, but we don’t know the sentence. Detained… we are tortured in so many ways. For example, rest.

For so many people in this tiny basement, sleep is forbidden. The regime’s rockets fall every ten minutes, ensuring that nobody is allowed to sleep…

From a small window in my group prison cell, the basement, I look at the world! The sky is so far away and hard to see, blocked by fighter-jets, MiGs, Sukhoi warplanes, and bombers. Our weather forecast is filled with barrel bombs and rockets, with a heavy hail of shrapnel.

During a lull in the bombing one of the mothers in the shelter took her son outside for some fresh air. When he returned he announced: ‘I saw them in the sky! One was black and the other white. The planes have eyes, and they were watching us.’

Somehow the front lines held through the first three weeks of February, and the map below (from Le Monde) shows the territories then still controlled by the main opposition groups: Jaish al-Islam on the east, centred on Douma; Failaq al-Rahman further west (the so-called ‘Central Section’), including the towns of Ayn Tarma, Irbin, Jobar and Zamalka, with some pockets under the sway of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS); and Ahrar al-Sham, which controlled Harasta.

But on 25 February – hard on the heels of a UN Security Council Resolution calling for a ceasefire from which unspecified ‘terrorists’ were excluded – the aerial assault was joined by a ground offensive spearheaded by tanks and armoured vehicles, and the situation changed rapidly and dramatically. The first map below plots major strikes by Russian and Syrian aircraft between 18 and 23 February; the second map (also from Le Monde) superimposes on this the direction of the initial ground attack.

This was a calculated change of strategy. Nawar Oliver explained that over the preceding six years the rebels had become experts in urban warfare (the photograph below shows JAI commanders working with a detailed map of the Ghouta); they knew every square metre of towns like Jobar and Ain Tarma in the west, where pro-government forces had tried time and time again to break through without success: so the Syrian Arab Army and its allies staged this new assault from the east and across open country. The rebels were ready for this too, but JAI accused Failaq al-Rahman of cutting water from the Barada River that was to have flooded a defensive trench system and so accelerating the advance of the Syrian Arab Army. In response, Failaq al-Rahman claimed to have been ‘stabbed in the back’ by JAI which, so it complained, had failed to hold the front line.

As the map from Le Monde shows, the rapid advance of pro-goverbment forces across a widening front was accompanied by a second, more concentrated assault from the west on the Harasta Farms area.

Realising that the ‘cease-fire’ was already a dead letter, thousand of people abandoned their homes. Here is one teacher, Sarah, describing the flight of her family:

When night fell [on 25 February], Sarah and her family decided to flee to a nearby basement that they hoped would be safer. To ensure the survival of some family members, they divided into three teams taking separate routes. When one missile fell, and then another, and another, they took shelter. “A missile hit the roof of the building where we were hiding, and the children cried more and more… We decided to run: whatever happens, never stop . . . . We ran, missiles came again, a child fell down. I carried her and kept running.” They finally made it to the basement, but it reminded her of one of “the regime’s prisons.” “There were about a hundred persons in a 150-square meter basement … No lighting, no water, no food…

The same stories were repeated, endless variations on a single theme: families running together and leaving virtually everything behind them. Here is a farmer from al-Shifouniyeh describing how his family fled to Douma from the rapidly advancing eastern front:

“The forces advanced into the farms…We lifted the kids and ran in the night… We don’t even have clothes… The warplanes and rocket launchers pounced. The bullets were reaching our building.” With their three children, he and his wife also live in a basement. “It’s disgusting,” Abu Firas added. “We want to return home…We have our lands. We abandoned them, our cows, our sheep.” The army now controls the village.

Not everyone abandoned their animals (above). According to the New York Times:

[S]ome [were] accompanied by their livestock as agricultural areas were lost… “The smell of rotten garbage is all around, in addition to animals’ smell,” said Thaer al-Dimashqi, an anti-government activist in Douma who uses an alias for safety, adding that 100 families had flooded into his neighborhood alone. “Sheep and cattle are surrounding my house — imagine, cows are being kept inside houses.”

Amidst this mounting chaos Syrian Arab Air Force helicopters were dropping thousands of leaflets (original and translation below) on Douma and the surrounding area calling on civilians to leave through a ‘humanitarian corridor’ that would be opened via the al-Wafideen crossing during a daily truce between 9 a.m. and 2 p.m., starting on 27 February:

Despite the risibly contrary claims from Damascus and Moscow that the Ghouta had been abandoned to ‘terrorists’, this was a clear admission that civilians were present and in grave danger. And, as Halim Shebiya underscored, issuing a warning did not nullify the legal requirement for attacks to be proportionate and confined to military targets. Although their tempo was reduced during the ‘pause’, however, air strikes and shelling continued – prompting one activist to demand how people could trust the forces carrying out the bombing to ensure their safety if they chose to evacuate – and there were also reports that rebels had shelled the corridor to prevent civilians from leaving. In any event, nobody did so.

Three days later the ceasefire collapsed. Fierce fighting continued to rage across the Ghouta: between 18 February (when the military offensive kicked off) and 3 March at least 1,000 people had been killed and 5,000 injured, many of them suffering acute trauma. These are minimum estimates, derived only from medical facilities supported by MSF (and even then, not all of them had reported), ‘meaning that the overall toll [was] significantly higher.’

Satellite imagery confirmed the extent of the physical devastation (see also here). The first map shows new physical damage between 3 December and 23 February; the orange cells show ‘minor damage’ caused between those dates, the red cells ‘major damage’. Analysis showed ‘29% of the cells were affected by major new damage, with presence of buildings completely destroyed or severely damaged between 3 December 2017 and 23 February 2018.’

This second map shows new physical damage between 23 February and 6 March, when ‘14% of the cells were affected by major new damage’. You can see the locus shifting from the west to the east with the ground offensive.

It bears repeating that these maps plot only new damage. To give you some idea of the base figures, in December 2017 analysis of satellite imagery revealed that 93 per cent of all the buildings in Jobar had been destroyed or damaged; 71 per cent in Ain Terma; 59 per cent in Zamalka (Douma was not included in the December survey).

As the perimeter of devastation widened, people continued to flee from the front lines and deeper into Ghouta, many of them displaced multiple times, but always more and more people crowding into a smaller and smaller space.

By 12 March pro-government forces had shrunk the space controlled by rebel groups in East Ghouta and the two ground offensives – across the wide front to the east and through the deepening wedge from the west – bisected and then rapidly trisected the area. They left behind scorched earth and towns of rubble.

Thousands of civilians had been displaced, but as this map from OCHA (dated 12 March) shows, virtually nobody had moved through the ‘humanitarian corridors’. A second had been opened from the zone controlled by Failaq al-Rahman to the south four days earlier, but there were reports that rebel snipers had ‘slammed shut’ both escape hatches.

The aerial assault never slackened, and the death toll mounted. As this map shows, the focus of air strikes and artillery bombardments shifted again, back from the east to the west, focusing on Harasta and the area to the south controlled by Failaq al-Rahman:

But conditions were also bleak to the north. By 12 March Ahmad, a member of a specialized team charged with collecting bodies – and body parts – from hospitals and clinics described scenes of utter horror in Douma:

Usually the family of the deceased is responsible for burying their relatives, but now the situation is catastrophic. Bodies are piling up at medical facilities as the bombings make it difficult for residents to go out and collect them. It doesn’t make sense for somebody to be killed because they are transporting and burying the dead….[so] there is more pressure on the transport teams and the civil defense…

Funeral ceremonies and services are now a forgotten matter. Even a proper grave is a luxury. Increasingly, we are resorting to mass graves…

The people of Ghouta are prevented from saying goodbye to their loved ones. The deceased arrives at the cemetery alone, or accompanied by one family member. Getting a white shroud for the deceased is just a dream. We are wrapping bodies in whatever we can get our hands on: cloth, blankets or plastic bags.

One week later and it was too dangerous to reach the graveyards even at night, and the dead were being buried in parks and backyards.

Eventually the pressure proved too much for many people to bear. Social media started to register the bone-weariness of the survivors – writing on Facebook from a basement crammed with 200 people, most of them women and children, Ward Mardini wrote ‘They’re all tired of shelling and siege’; ‘We believe that the Ghouta is precious for you,’ she told rebel commanders, ‘but we’re tired and the situation demands a realistic solution that stanches the waterfall of blood’ – and there were protests in Kafr Batna and Hammouriyeh calling on the rebels to leave.

On 15 March Josie Ensor reported:

Hammouriyeh’s residents have borne the brunt in the last few days with a relentless onslaught of barrel bombs, mortars and chemical strikes, until surrender looked to be the only remaining option. The last of the messages from inside Hammouriyeh came in the middle of the night on Wednesday [14 March]. “More than 5,000 people are at risk of annihilation,” a doctor in the town said via [WhatsApp] text. “Please get our voice out to the world, this might be the last message I’m able to send. The wounded are in the streets and cannot be moved and the planes are targeting any movement. I witnessed an entire family getting killed in front of me by air strikes, I’m by a basement trying to send this message.” The internet connection in the town went down shortly after and their fate is unknown.

The barrage was so intense that for most people escape to other areas in the Ghouta was blocked, and the dam burst early the next morning. On 15 March thousands of civilians started to stream out from Hammouriyeh on foot – as many as 15,000 by nightfall – running the gauntlet of Syrian television cameras:

Throughout the day, Syrian state television broadcast live coverage of columns of families walking out of the town toward Syrian government lines, clutching children, suitcases and plastic bags of belongings. Men were bowed under heavy suitcases. Women carried children and torn plastic bags of clothes. An injured, blood soaked man was carried on a stretcher. An elderly man pushed his wife in a wheelchair, another walked with a herd of cows….

Some walked silently past the camera, turning their faces away and refusing to talk….

Later Thursday afternoon, state television began broadcasting from inside the recaptured town, where many thousands of people were milling in the streets with suitcases and bundles, preparing to leave. Pick up trucks, Syrian army vehicles and buses then arrived and residents piled furniture and mattresses on board as they were escorted out of the town.

The refugees streamed east towards Hawsh al-Ashaari and newly-occupied government territory aiming for Adra:

Elsewhere, the assault continued without slackening, and people continued to flee the onslaught. Those who managed to escape Hammouriyeh for shelter elsewhere in the Ghouta found respite but few found refuge. ‘We don’t know what will happen,” one exhausted man told the New York Times in a voice message, ‘the sound of rocket fire in the background. “I run to Hammouriyeh, they bomb it. I run to Zamalka, more bombing is ahead of us”’ (he was right; the photograph below by Abdulmonam Eassa shows Zamalka on 24 March).

Everywhere the refugees were met by new horrors. Nivin and her son and daughter were forced to leave their basement and flee again on 16 March:

Everywhere the refugees were met by new horrors. Nivin and her son and daughter were forced to leave their basement and flee again on 16 March:

It’s like Judgement Day… people are running and screaming. People in their nightgowns and people barefoot. Cars loaded with people, speeding around at over 100 [km/h]. And I too am screaming, looking at what I see around me. Usually these kinds of posts end with me waking up and realizing it was all just a nightmare. I wish it were a nightmare. But it’s not. Our days are worse than nightmares. I’m running while holding my daughter’s hand, my eyes are on my son. A five-year-old girl is crying out and yelling: “Tell them, tell them not to kill us!” But I don’t have any answer to calm her down.

There is a helicopter directly over our heads right now, and it seems to be spinning slowly as it showers the neighborhood with bombs.

The photographer Abdulmonam Eassa, writing from Ain Terma on 21 March (he was transferred from Arbin to Idlib two days later):

I have been moving from one area to the next since March 15, when I left Hammouriyeh, my hometown. The bombing wasn’t even the main reason why I left – it was the clashes and the regime’s advance. I spend most of my time cowering in basements.

I am walking in a neighbourhood of Ain Terma. The road is very narrow and there is a woman and her child walking near me. A shell hits. It’s three or four metres away from me, but very close to the woman and the child. I don’t feel anything for several minutes. Then I feel a massive shock. I look around. The child is on the ground, crying. I pick him up. There is no one else around. His mother is on the ground. She is dead. I pick him up and run to the entrance of a nearby building. Another shell hits. I put the kid on the ground. His foot is almost detached. I try to hold it in place. I pick him up and run with him through the streets. They are truly the streets of death.

The net continued to close. By then the Syrian Arab Army and its allies had captured around 80 per cent of East Ghouta, and that same day (21 March) Russian forces brokered a deal between Ahrar al-Sham and the Syrian government to allow fighters and their families to be removed from Harasta to rebel-held Idlib; buses started to arrive early the next morning for the forcible transfer of thousands of people. Those who elected to stay were given guarantees ‘that no harm [would] come to them.’

Two days later (23 March) Failaq al-Rahman concluded a similar agreement covering the towns of Arbin, Zamalka, Ain Terma and Jobar. The sick and wounded would be evacuated immediately. Then fighters, their families and any civilians who wanted to leave with them would be taken by bus to Idlib – al Jazeera explained that ‘other civilians are leaving as well, people who were involved in opposition activities like media activists, medics, civil defence volunteers’ because they ‘are considered terrorists by the Syrian government so they cannot stay’ – while those who chose to remain were assured that they would not be prosecuted provided they ‘reconciled‘.

These were difficult, traumatic decisions that often divided families, and in a later post I’ll discuss the fate of the deportees, those who moved to nearby resettlement camps and government shelters (usually with the desperate hope of returning to Ghouta in an uncertain future), and those who stayed in what was left of their homes. But these capitulations left Jaish al-Islam isolated in its stronghold of Douma. There were reports that JAI was preventing civilians from leaving the town, who were caught between the fear of being shot and the fear of being bombed, but small groups of exhausted people fled on foot through the al-Wafideen corridor. According to a spokesperson for the International Committeee of the Red Cross,

“People are very exhausted, as they spent days on the move before reaching the shelters, with the clothes they wear as sole belongings. One woman was telling me that she had to throw on the road the few clothes she managed to bring for her and her children, as it became too heavy to carry them while walking for many hours before reaching the crossing point.”

They were taking precious advantage of an uneasy truce that lasted for ten days – broken by intermittent air strikes – while JAI negotiated terms. Some of its members wanted to fight on, while others wanted to leave with their families but refused to go to Idlib: not only was the rebel-held area widely regarded as Assad’s next killing ground, an elaborately constructed shooting gallery where the offensive would soon be resumed, but JAI had a ‘blood feud’ with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham which controlled much of the area.

Some medical evacuations of the sick and wounded were successfully completed, and there were reports that transfers of some JAI fighters to Jarablus (in the Turkish-occupied north of Syria) had taken place too, but further negotiations stalled and eventually broke down. JAI reportedly placed new conditions on subsequent transfers and refused to release prisoners it had held captive for several years, and on the afternoon of 6 April it shelled Damascus, killing four and wounding another 22. The assault by the Syrian Arab Army and its allies immediately resumed with a vengeance. A ground offensive was launched under the cover of a sustained air and artillery bombardment broadcast live on state TV.

Haitham Bakkar sent this urgent message from Douma:

We are being wiped out right now. We are being bombarded with barrel bombs and rocket launchers. The town is overcrowded and many people have no place to hide.

Meanwhile, against the grain of the preceding paragraphs – every single one of them – here is Robert Fisk reporting from the territory regained by the Syrian Arab Army and its allies in East Ghouta on 4 April. Comparing its soldiers to the French poilus on the Western Front (the geopolitics of that metaphor bears reflection), Fisk was nonetheless puzzled by their failure to dig any trenches, a staple of wars of attrition – and yet, he continued, that explained their shock when they burst through the front lines. Here is one of them:

I have never seen so many tunnels. They had built tunnels everywhere. They were deep and they ran beneath shops and mosques and hospitals and homes and apartment blocks and roads and fields. I went into one with full electric lighting, the lamps strung out for hundreds of yards. I walked half a mile through it. They were safe there. So were the civilians who hid in the same tunnels.

Think, now, of the weight of that last sentence pressing on my previous paragraphs. Fisk had already prepared the ground for it: ‘Why the wasteland of homes and streets,’ he asked, ‘and how did so many of the civilians survive…?’ And in case you missed it, he repeated the conclusion of his informant without qualification: the tunnels ‘are deep and dank and glisten with moisture. But they are safe.’

Fisk (above) was not wrong about the rebels’ mastery of underground operations. As the Syrian Arab Army advanced from the east it encountered a formidable trench system cutting across the rural landscape, and as this satellite image reveals there were trenches carved across the heart of Ghouta too (those brown scars):

Here is a ground view of a trench connecting Harasta and Ain Terma:

The trenches would obviously have been exposed to air attack, but the tunnels were a different story. Those dug to connect East Ghouta with Barzeh and al-Qaboun were common knowledge (more here, including maps); they had all been blown by pro-government forces during their offensive the previous year. But there were also tunnels inside Ghouta. When Jobar, Ain Terma and Zamalka fell, Syrian troops discovered ‘a spider’s web’ of tunnels running for 5 km between the three towns, excavated under the orders of Failaq al-Rahman. The major ones were 15 metres deep, their walls reinforced with steel rods and fitted with lights and even surveillance cameras. These were wide enough to drive a vehicle through; others were accessible only on foot.

The trenches would obviously have been exposed to air attack, but the tunnels were a different story. Those dug to connect East Ghouta with Barzeh and al-Qaboun were common knowledge (more here, including maps); they had all been blown by pro-government forces during their offensive the previous year. But there were also tunnels inside Ghouta. When Jobar, Ain Terma and Zamalka fell, Syrian troops discovered ‘a spider’s web’ of tunnels running for 5 km between the three towns, excavated under the orders of Failaq al-Rahman. The major ones were 15 metres deep, their walls reinforced with steel rods and fitted with lights and even surveillance cameras. These were wide enough to drive a vehicle through; others were accessible only on foot.

During the negotiations with Jaish al-Islam, one of the Russian demands was for maps of its tunnel system, which supposedly linked Douma with al-Shifouniyeh to the east and Misraba to the south-west (one of the tunnels is shown under construction below).

I haven’t been able to discover how extensive the system was (or, given the friction between the rebel groups, whether it was a system at all). It may be that some of the tunnels and trenches were connected, and the basements of new buildings in Douma were often connected to the subterranean grid. Still, I suspect that the Army officer who told CNN that ‘all of Ghouta is connected by tunnels’ was exaggerating; there must have been huge swathes of territory outside the networks. And given the often ambivalent and sometimes antagonistic relations between rebels and civilians, it’s unlikely that many people found sanctuary in the tunnels with the rebels: first-person testimonies describe, almost without exception, families leading a wretched existence in crowded, unsanitary basements and shelters.

Fisk’s report never mentions the shelters in which most of the besieged population sought refuge of sorts but instead elaborates the safety of the tunnels. You might wonder why, if the people of East Ghouta were so safe and had so little to fear from the advancing Syrian Arab Army and its allies, they should have risked their lives to flee not once but multiple times.

For most people it was about degrees of danger: as the offensive intensified, being outside and above ground was to court almost certain death – ‘a suicide mission‘ according to Bayan Rehan, a member of the Women’s Council in Douma, ‘like playing Russian roulette‘, according to Ahmad Khanshour, another community activist in Douma – but being underground was far from safe. Most of the shelters were makeshift affairs. Here is one young mother who fled with her husband and daughter to ‘the only underground shelter’ in Saqba:

The dusty basement they now shared with 14 other families was once used as a warehouse by a furniture merchant. After removing useless furniture, they laid out mattresses and hung up curtains for a bathroom. The men tried to fortify the basement with sandbags meant to help absorb the blasts or shrapnel from barrel bombs.

Across Eastern Ghouta, which contains three cities and 14 towns including Saqba, residents worry whether their underground shelters will be sturdy enough to protect them…

Other families hastily dug shelters underneath their homes; the scene below is from a house in Hammouriyeh:

Unlike the tunnels, shelters like these had few if any facilities – no electricity, running water or sanitation and poor ventilation – and they were not reinforced with steel (or very much at all):

Under cracked ceilings that bulge downwards from the force of previous strikes, they string sheets across the basement to partition off rooms for entire families.

“Look at it. It is completely uninhabitable. It is not even safe to put chickens in. There is no bathroom, just one toilet, and there are 300 people,” said a man in a shelter in the region’s biggest urban centre, Douma….

Overhead, steel rebars were visible in the large cracks and depressions of a concrete ceiling that seemed poised to collapse over the shelter’s terrified inhabitants at any new blast nearby.

Apart from the fear of being buried alive if the building collapsed – many called the shelters ‘graves’ or ‘tombs’ – there were other dangers. ‘It is the closest place considered safe,’ said one young teacher. ‘But it is not safe. The barrel bomb sometimes lands at the shelter. Either at the door or inside, injuring or killing many.’ Even if people were too scared to go outside, they often stood near the entrance to get air (or cellphone reception) and were exposed to danger. Here is Nivin Hotary again:

I was standing by the cellar door trying to get cellphone reception. A cluster bomb fell and there were explosions all around me. One explosion was only about a meter from the cellar door. I saw a big fire and heard a deafening sound. I ran down the steps, and the fire followed me…. On a night not long ago, rockets fell somewhere nearby. The pressure of exploding iron spins you around.

And of course buildings did collapse – Nivin explained that ‘they tried everything to bury us alive in the basements’ – but even if the concrete and breeze-block withstood the blast from the bombs and shells, death could still penetrate the interior. There was the ever-present fear of chlorine gas, and in anticipation of another attack – the possibility was on everyone’s lips – people in the basements made improvised masks with charcoal.

The danger was acute because chlorine gas is heavier than air and seeps into basements and cellars. Nivin again, on 22 March:

A white wave – I saw it from my spot – descending the stairs and filling the whole width of the staircase. Afterwards it entered through the door of the room where we were, and spread. And it entered the men’s room. In seconds it filled the space, such that those around me started shouting: who switched off the light! The light didn’t switch off but the white wave filled the space..

From the moment it entered through the door, the man yelled to us one word: “Chloooride”..

Neither were those in the basements and shelters shielded from other, still more deadly weapons. Thermobaric bombs were used throughout the offensive; they disperse an explosive cloud into the air that detonates in an intense fireball accompanied by a high-pressure shock wave that can reverberate, ‘hitting the people inside at high force over and over again.’ Perhaps that is what Nivin described in her first report (above), in which case she had an extremely narrow escape.

Phosphorus and napalm (above) were used time and time again, and on 23 March al Jazeera reported:

“An air strike targeted one of the underground cellars in Irbin last night where between 117 to 125 people, mostly women and children, were hiding,” Izzet Muslimani, an activist in Eastern Ghouta, told Al Jazeera.

Abul Yusr, an activist and citizen journalist in Irbin told Al Jazeera that the death toll was 45, and that the air raid had hit two shelters connected to one another by a corridor, leading to one becoming completely destroyed.

“The air strike entered through one shelter, where it exploded and killed everyone in it. The fires spread through to the second shelter, which soon became totally engulfed in flames,” Abul Yusr told Aljazeera.

“Some people managed to escape the fire in the second shelter, but their injuries are quite severe.”

On 7 April one of the most feared weapons of all was used against people sheltering in two buildings in Douma (though Fisk was at pains to cast doubt on that too). I’ve discussed this in detail in ‘Gas masques‘, so I will simply repeat that the ‘shelters’ afforded no protection against chemical weapons either (in fact, the basement of one of the buildings turned out to be a death-trap). JAI capitulated almost immediately, and another round of forcible displacements was set in train.

Dying and mourning

The trauma experienced by the residents of East Ghouta did not end with the siege (if it has indeed ended), and I’ll explore its continued slow violence in a later post. When I wrote ‘The everywhere war’ I emphasised ‘the emergent, “event-ful” quality of contemporary violence, what Frédéric Gros saw as “moments of pure laceration” that puncture the everyday’, but I’d now want to qualify that (and will do so in a subsequent essay) because it privileges particular modalities of later modern war and marginalises others. Siege warfare in Syria and elsewhere has been punctuated by moments of spectacular excess – the chemical weapons attacks, the cataclysmic bombardments, the attacks on hospitals – but it has also been characterised by a constant, background rhythm of violence (bombing and shelling, deprivation and malnutrition) that became ‘the everyday’, a ‘new normal’ endured by the besieged population but more or less accepted by outside observers.

Yet that compromised everyday also included ways of being in the world that were precious, freighted with communion and compassion, which became occasions for mourning when it was time to leave. Some of those forcibly displaced described leaving as itself a form of dying. Here is Muataz Sameh, originally from Hammouriyeh, who worked as a nurse in a field hospital:

Leaving, it is as though I have died.

I will miss my home. I will miss my mother and my sister, who have left for the shelters [in Damascus]. I have heard nothing from them, no news to console me.