For an update and succinct review of attacks on hospitals and medical facilities in Syria – see also my ‘Your turn, doctor’ here – I recommend the latest fact-sheet from Physicians for Human Rights:

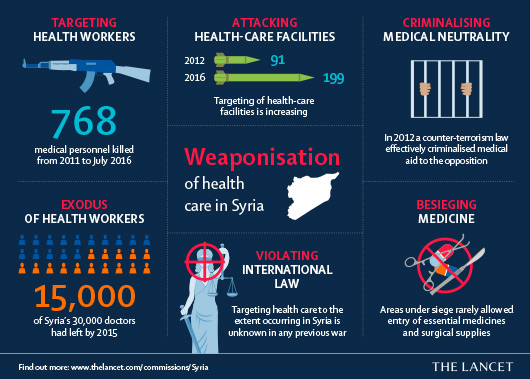

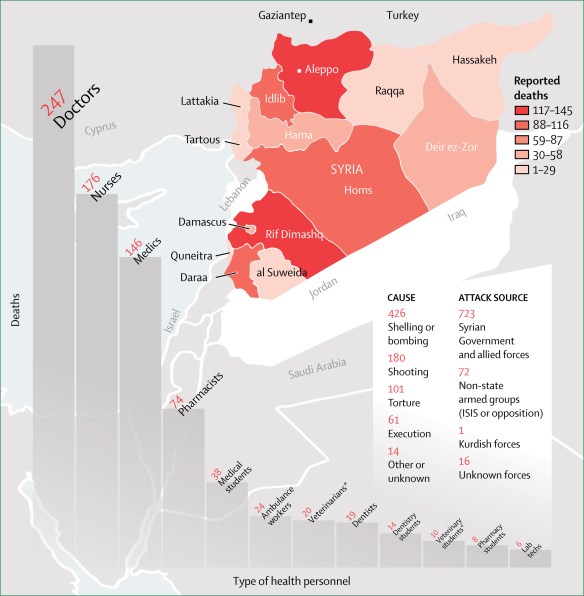

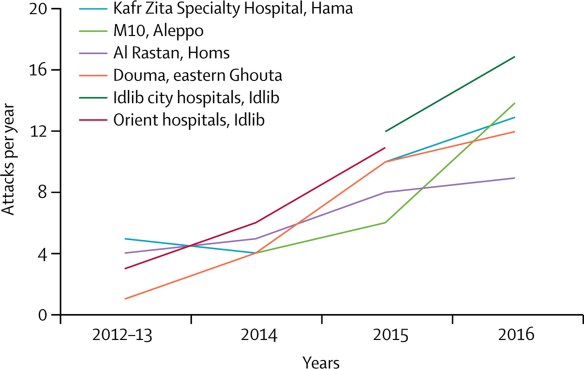

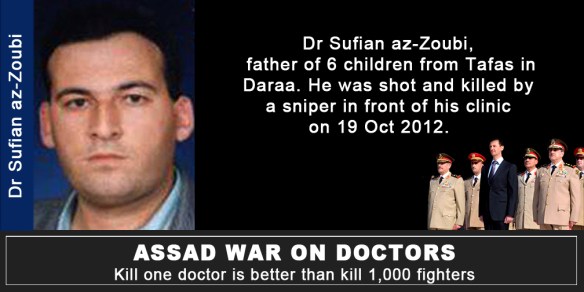

Attacks on health care, in gross violation of humanitarian norms and the Geneva Conventions, have been a distinctive feature of the conflict in Syria since its inception. PHR has documented and mapped 553 attacks on at least 348 separate facilities from March 2011 through December 2018. The reduction in the number of attacks over the past year is a clear reflection of the diminishing intensity of the conflict, which came as a direct result of the Syrian government’s takeover of most opposition-held areas. The systematic targeting of health facilities has been a crucial component of a wider strategy of war employed by the Syrian government and its allies – who are responsible for over 90 percent of attacks – to punish civilians residing in opposition- held territories, destroy their ability to survive, and draw them into government-held areas or drive them out of the country. This strategy of unbridled violence – which in addition to attacks on healthcare has included chemical strikes, sieges, and indiscriminate bombing of predominantly civilian areas – has devastated the civilian population, weakened opposition groups, and translated into direct military gains for the Syrian government.

Of the total number of documented attacks on health facilities, nearly 73 percent were carried out from the air. Nearly 98 percent of attacks on health facilities perpetrated from the air are attributable to the Syrian government and its ally Russian, which entered the conflict in 2015.

The share of attacks on health facilities from the air has grown from 38 percent of the total in 2012 to 90 percent in 2018. The Syrian government became steadily more reliant on airpower as the conflict evolved. Through their air forces, the Syrian government and Russia extended their strategy of collective punishment deep into opposition-held territory and far beyond hardened front lines. The Syrian government and its allies disabled or destroyed hundreds of facilities through aerial bombardment, leaving countless civilians without access to vital medical services.

The latest 20-page report from the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic to the UN’s Human Rights Council is here. I’ve drawn on many of these reports for my continuing work on siege warfare in Syria (see for example here, here and here), and this report – based on investigations carried out from 11 July 2018 to 10 January 2019 – makes for grim reading. Here is the summary (but you really need to consult the full report):

Extensive military gains made by pro-government forces throughout the first half of 2018, coupled with an agreement between Turkey and the Russian Federation to establish a demilitarized zone in the north-west, led to a significant decrease in armed conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic in the period from mid July 2018 to mid January 2019. Hostilities elsewhere, however, remain ongoing. Attacks by pro-government forces in Idlib and western Aleppo Governorates, and those carried out by the Syrian Democratic Forces and the international coalition in Dayr al-Zawr Governorate, continue to cause scores of civilian casualties.

In the aftermath of bombardments, civilians countrywide suffered the effects of a general absence of the rule of law. Numerous civilians were detained arbitrarily or abducted by members of armed groups and criminal gangs and held hostage for ransom in their strongholds in Idlib and northern Aleppo. Similarly, with the conclusion of Operation Olive Branch by Turkey in March 2018, arbitrary arrests and detentions became pervasive throughout Afrin District (Aleppo).

In areas recently retaken by pro-government forces, including eastern Ghouta (Rif Dimashq) and Dar’a Governorate, cases of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance were perpetrated with impunity. After years of living under siege, many civilians in areas recaptured by pro-government forces also faced numerous administrative and legal obstacles to access key services.

The foregoing violations and general absence of the rule of law paint a stark reality for civilians countrywide, including for 6.2 million internally displaced persons and 5.6 million refugees seeking to return. For these reasons, any plans for the return of those displaced both within and outside of the Syrian Arab Republic must incorporate a rights- based approach. In order to address effectively the complex issue of returns, the Commission makes a series of pragmatic recommendations for the sustainable return of all displaced Syrian women, men and children.

A report from Elizabeth Tsurkov in Ha’aretz confirms many of these findings. Describing Assad’s Syria as a police state with rampant poverty’ and a ‘playground for superpowers’, she writes:

Eight years into the crisis, Syria’s economy is in tatters, half of its population displaced, hundreds of thousands of Syrians are dead, many of Syria’s cities and towns lie in ruins. Yet on top of this pile of ashes Assad sits comfortably, quite secure in his grip on power.

In areas reconquered by the regime — or as the regime euphemistically describes it, areas that “reconciled” and whose residents “returned to the bosom of the nation” — the Syrian police state is back, more aggressive than ever…In 2011, Syrians took pride in “breaking the barrier of fear.” But fear now prevails, as the various branches of the regime’s secret police launch raids and arrest suspected disloyal elements. Many of those arrested are former activists, rebels, health and rescue workers, and civil society leaders. Syrians who wish to prove their loyalty to the regime, obtain power through it or simply settle personal scores inform on others to the regime. Suhail al-Ghazi, a Syrian analyst based in Istanbul, told Haaretz that Syrians are informing on each other “because they have been doing it for years or because they need money or favors from the regime.” In areas recently recaptured by the regime, “some locals were always pro-regime and stayed there to work as informants or just could not leave. Now they have the chance to take revenge on the majority of civilians who apparently held a more favorable view of the opposition,” Ghazi explained.

Most of Syria’s population now lives below the poverty line. Across all parts of Syria unemployment rates are high, as the normal economy has been disrupted by years of war and the mass flight of businesspeople and capital out of the country. Syria’s middle class has largely disappeared — many of them fled to neighboring countries or Europe, while others are now living in abject poverty, along with most Syrians.

A small group of war profiteers linked to the various armed groups have been able to enrich themselves by trading in oil, weapons, antiquities, stealing aid, and smuggling people and goods in and out of the country and into besieged areas, while most Syrians struggle to survive. Nearly two-thirds of Syrians are dependent on aid for their subsistence. Basic services like electricity, cooking gas, clean water and health services are lacking in many parts of the country.Speaking on the condition of anonymity, a resident of Latakia — an area where many of the regime’s leadership and their relatives reside — told Haaretz: “You have corruption everywhere. Bribing was common before the war, but now it is endemic.”

He described the ostentatious displays of ill-gotten wealth: “High-ranking officials, they and their families, have more rights. They roam the city in fancy cars and do whatever they want. Half of the country is dying from hunger, while the sons of officials are arrogantly showing off their wealth. With money you can do everything. This is not new, but it has become more obvious because of the lawlessness prevailing in Syria.”

At the sub-regional scale Enab Baladi filed a revealing report last month on conditions in the Ghouta (which it describes as ‘military-ruled ruins’):

Today, Ghouta is living in a state of siege similar to that it witnessed between 2013 and 2018 at the service, relief and security levels, but the difference is that food is available.

With dozens of announcements about the restoration of electricity to areas east of the capital, as well as the restoration of water and communication services, the needs of civilians are still not covered by those services repeatedly announced by the regime.

Enab Baladi spoke to five people from the eastern Ghouta who returned to it, all of whom refused to be identified for fear of the regime prosecution. They described the service situation as “miserable”, especially with regard to the water and electricity services.

According to the five sources, the electricity is continuously cut for five hours, operates for only one hour, and then it is cut again, while water reaches homes one hour a day, and people rely on submersibles and artesian wells which they dug during siege in the previous years to get water.

Some areas of Ghouta also lacked many of the services that were the top priorities of organizations before the regime forces controlled the region, while food today enters without manipulated prices, unlike in the past….

The report describes Eastern Ghouta as riven by checkpoints; an emphasis on demolition rather than reconstruction; and continuing arrests and detentions.

In early August [2018], al-Assad forces launched a campaign of arrests, which has been considered as one of the largest security operations since the regime took over Ghouta, for it has targeted the regime dissidents and activists in the Syrian revolution. The campaign was carried out in the cities and towns of Saqba, Hamuriyah, Duma, Mesraba, and Ein Tarma.

The regime also subjected local activists, civil society workers, and former media professionals, as well as members of local councils and relief agencies, to investigations into the aids they received when the area was held by the opposition.

Security branches launched arrest campaigns targeting members of the former “local council” and other members of Rif-Dimashq Provincial Council in the city of Kafr Batna in central Ghouta, according to Enab Baladi referring to local sources.

Sources affiliated to the council told Enab Baladi that Syrian security forces raided the houses and workplaces of the detainees before taking them to an unknown destination. Other local council members, who preferred to stay in Ghouta rather than go to northern Syria, are detained for the same reasons.

In the face of all that, it’s not easy to find grounds for optimism, but there is a glimmer of hope in a report from Maryam Saleh at The Intercept:

Syrian activists and lawyers are testing the bounds of international law, making two new attempts to bring the government of Bashar al-Assad before the International Criminal Court.

Syrian refugees in Jordan, through London-based lawyers, sent communications to the office of the ICC prosecutor, asking her to exercise jurisdiction over Syria based on a precedent set last year in a case involving Myanmar’s persecution of Rohingya Muslims. The communications are the latest push by Syrian civilians to hold accountable the government whose brutality upended their lives. In recent years, Syrian lawyers and human rights activists have experimented with rarely utilized aspects of international law, succeeding in getting European and American courts to weigh in on atrocities committed in Syria.

“Because of how politicized the war in Syria became, lawyers and those fighting for accountability really had to be creative,” said Mai El-Sadany, the legal and judicial director at the Washington-based Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. “The most recent ICC Article 15 submissions” — a reference to communications with the ICC on information about alleged international crimes — “are evidence of this, that there is space for creativity in the accountability space.”

She continues:

Even when the evidence of potential crimes exists, investigations into crimes committed in states that have not ratified the Rome Statute are near impossible because of jurisdictional issues, and U.N. Security Council members are quick to use their veto power to block investigations into crimes potentially committed by their allies.

That’s what makes the various avenues Syrians are pursuing so significant. As of last March, more than two dozen cases had been filed in European courts regarding atrocities committed by the Syrian regime, rebel fighters, and the Islamic State and other fundamentalist militant groups. The family of Marie Colvin, an American journalist killed in 2012 while reporting from the city of Homs, sued the Syrian government in a U.S. district court; in January, the court found Syria responsible for killing Colvin.

Many of the cases in Europe were brought under a legal doctrine known as universal jurisdiction; application of the doctrine varies from country to country, but it essentially allows for courts to prosecute cases regardless of where the crime was committed or whether the accused party has any links to the prosecuting state.

The biggest success so far has been in Germany, where authorities last month arrested a former high-ranking Syrian intelligence officer and two others who are accused of crimes against humanity for torturing detainees in Syrian prisons. Other cases remain pending in France, Sweden, and Spain….

These attempts are possible in part due to an unprecedented level of documentation of crimes in Syria. The victims in some of the cases were identified from a trove of 28,000 photos of people killed in Syrian detention centers, smuggled out of the country by a military defector codenamed Caesar. The U.N. General Assembly, in December 2016, took the step of creating the International, Impartial, and Independent Mechanism to investigate crimes in Syria since 2011. The IIIM, as the body is known, does not have independent prosecutorial authority, but it exists to collect information that could later be provided to courts or tribunals with jurisdiction over the crimes. Last year, 28 Syrian nongovernmental organizations committed to collaborating with the IIIM on its work.

This is heartening in its way, but whenever I’ve been asked about attempts to enforce accountability in relation to the systematic attacks on hospitals, I’ve had to say that the hideous intimacy between torturer and tortured allows for an identification and assignment of culpability that is much more difficult in the case of the extended ‘kill-chain’ involved in bombing.

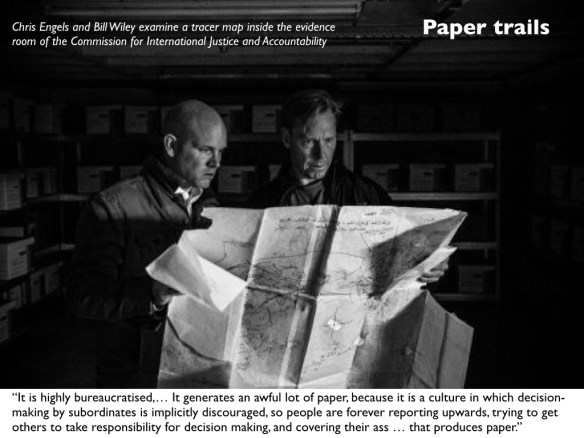

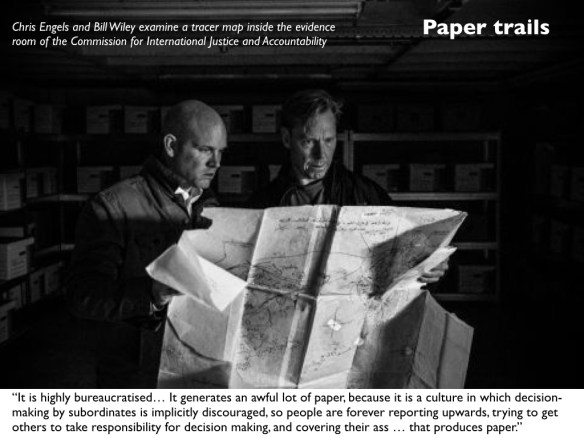

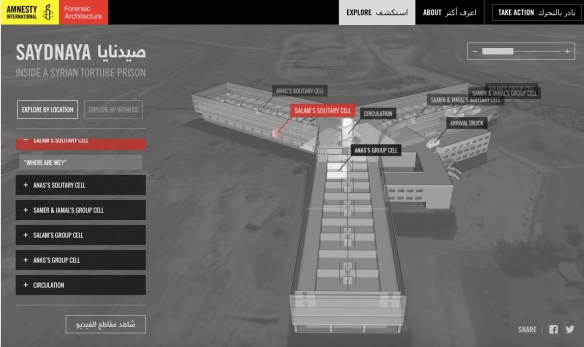

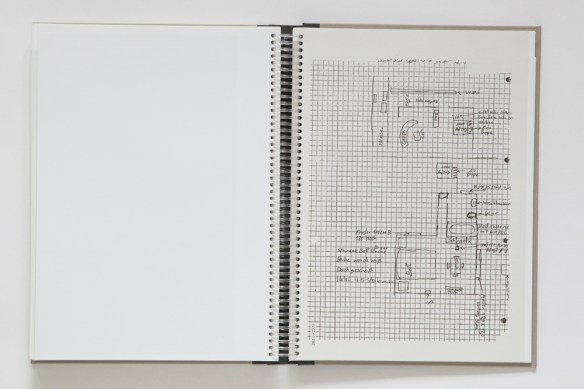

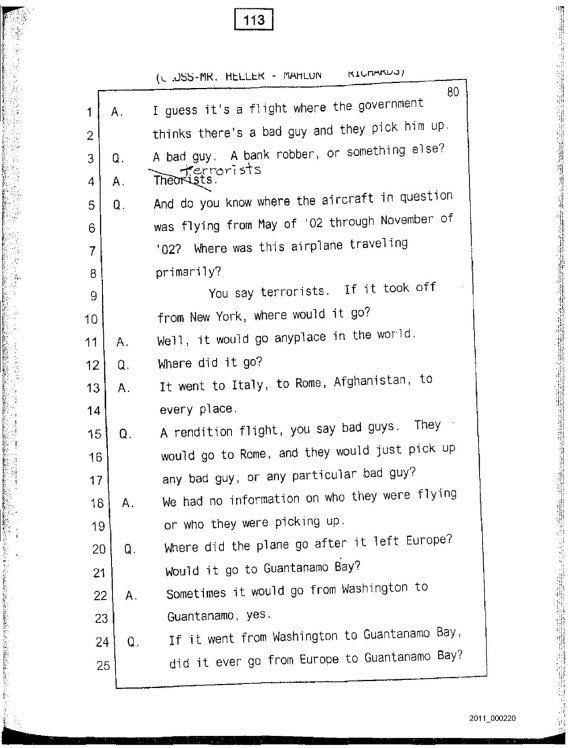

But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible: we know, from the courageous work of activists cited in Maryam’s report, that Assad’s security apparatus fetishized record-keeping, and that many of those records have been smuggled out of Syria so that they can now serve as testimony and evidence (For other testimonies, see the work of Forensic Architecture on Saydnaya Prison that I described here: scroll down). To sharpen the point, hare some of the slides from a presentation I once gave around precisely these questions:

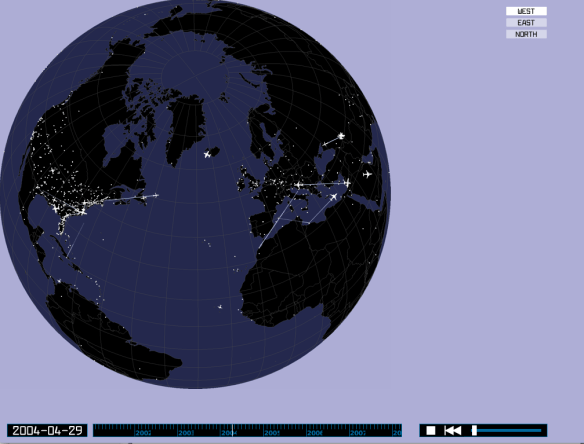

If my work on bombing in other theatres of war is anything to go by, there will also be extensive trails (paper or digital) that animated the air strikes: though how they can ever be exposed is another question.