I woke this morning to media reports of the continued carnage in Gaza and to headlines recycled from Associated Press announcing that Israel had struck ‘symbols of Hamas power’. Front and centre in the frenzied assault was an attack on Gaza’s only power station: but its importance is hardly ‘symbolic’.

In Targets of opportunity Samuel Weber wrote: ‘Every target is inscribed in a network or chain of events that inevitably exceeds the opportunity that can be seized or the horizon that can be seen.’

In Targets of opportunity Samuel Weber wrote: ‘Every target is inscribed in a network or chain of events that inevitably exceeds the opportunity that can be seized or the horizon that can be seen.’

In ‘In another time-zone…’ (DOWNLOADS tab) I elaborated his comment in relation to so-called ‘deliberative targeting’, which ‘places a logistical value on targets through their carefully calibrated, strategic position within the infrastructural networks that are the very fibres of modern society’:

The complex geometries of these networks then displace the pinpoint co-ordinates of ‘precision’ weapons and ‘smart bombs’ so that their effects surge far beyond any immediate or localised destruction. Their impacts ripple outwards through the network, extending the envelope of destruction in space and time, and yet the syntax of targeting – with its implication of isolating an objective – distracts attention from the cascade of destruction deliberately set in train. In exactly this spirit, British and American attacks on Iraqi power stations in 2003 were designed to disrupt not only the supply of electricity but also the pumping of water and the treatment of sewage that this made possible, with predictable (and predicted) consequences for public health. Similarly, on 28 June 2006, during the IDF’s Operation Summer Rains, Israeli missiles destroyed all six transformers of Gaza’s only power station (which provided over half of Gaza’s power). Being powerless in Gaza was as devastating as in Iraq:

‘The lack of electricity means sewage cannot be treated, increasing the risk of disease spreading, and hospitals cannot function normally. It means ordinary Gazans cannot keep perishable food because their fridges do not work. At night, they are plunged into complete darkness when the electricity cuts off. They rely on candles and paraffin lamps. Many residents have also been left with an irregular water supply as they need electricity to pump water up from nearby wells or from ground floor level to higher floors in blocks of flats.’

In attacking the power station – a repeated and familiar target, and so not one struck ‘by accident’ – the IDF knows very well that in the days, weeks and months to come hundreds, even thousands of people will get sick or even die as sewage plants and water pumps fail, as refrigeration systems stop, and as essential surgeries and life-support systems are interrupted.

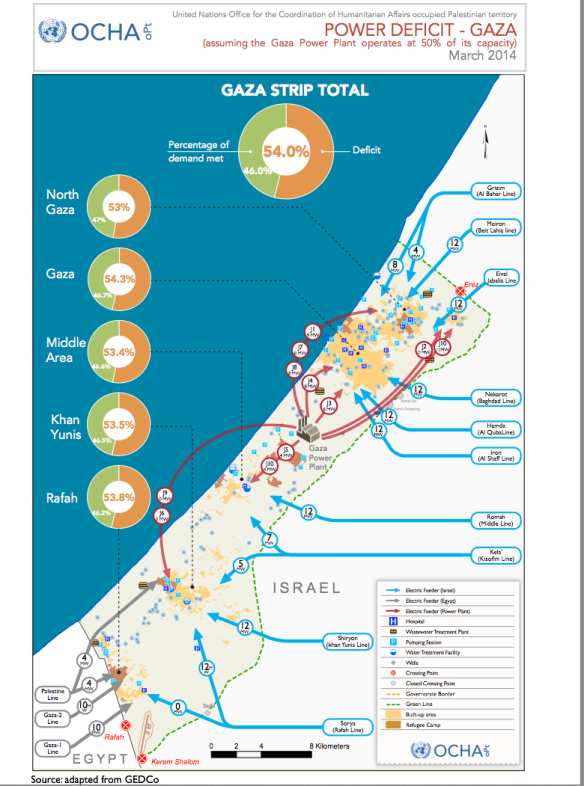

The situation before the latest Israeli offensive was highly precarious, as the map below shows; you can download a hi-res version here (if you have power), and the accompanying one-page report spells out the implications. Israeli restrictions on the importation of spare parts mean that the power plant has never been restored to full capacity after the previous attacks, and since June 2013 the situation has been exacerbated by ‘the halt in the smuggling of Egyptian-subsidized fuel used to operate the [power plant] via the tunnels’ (last year the differential was 3.2 shekels/litre compared with 7.1 shekels/litre for fuel imported from Israel).

At full capacity, Fares Akram reports, the power station should supply 80 megawatts of electricity; before the most recent Israeli offensive it was already degraded, producing at most only 50-60 megawatts. It was damaged by Israeli shelling three times last week, and the effects tore into what was left of the fabric of everyday life. Listen to Atef Abu Saif, writing in his ‘Diary of a Palestinian’ on Saturday 26 July (and read the whole thing: it is an astonishing and eloquent testimony to the depravity of the onslaught):

It has now been 40 hours with no electricity. The water was also cut off yesterday. Electricity is a constant issue in Gaza. Since the Strip’s only power station was bombed in 2008, Gazans have had at best 12 hours of electricity a day. These 12 hours could be during the day, or while you are fast asleep; it’s impossible to predict. Complaining about it gets you nowhere. For three weeks we’ve barely had two or three hours a day. And right now, we would be happy with just one.

These blackouts affect every part of your life. Your day revolves around that precious moment the power comes back on. You have to make the most of every last second of it. First, you charge every piece of equipment that has a battery: your mobile, laptop, torches, radio, etc. Second, you try not to use any equipment while it’s being charged – to make the most of that charge. Next you have to make some hard decisions about which phone calls to take, which emails or messages to reply to. Even when you make a call, you have to stop yourself from straying into any “normal” areas of conversation – they’re a waste of power.

And remember that without those mobiles and laptops much of what the IDF has done would not reach the outside world: see this report , for example, which describes how 16 year old Farah Baker (@Farah_Gazan), ‘one of Gaza’s most powerful online voices’ with over 70,000 Twitter followers, was abruptly silenced when she was unable to charge her phone.

Last night the power plant was hit by Israeli tank shells again – the IDF spokesman insists that the plant ‘was not a target’: just how many times do you have to strike something before you recognise what it is? – and now it has been forced to shut down completely. You can watch a video interview with Sara Badiei, an ICRC water and sanitation engineer in Gaza, who describes the knock-on effects of the power shut-down here:

‘If there is no electricity, there is no water, and I want to make that clear… Water needs to be pushed down the lines, down these tubes, you need pumps to be able to run to bring the water out of the well, to push it down the line and to deliver it to the population. If there’s no electricity, that can’t happen…’

Gaza also relies on 10 power lines from Israel and Egypt to provide an additional 120 megawatts but 8 of these have been cut by Israeli shelling. In the interview, Sara explains that it takes 5-7 days to repair each line and it is, of course, extremely dangerous work in a war-zone under constant Israeli shelling.

This is not ‘symbolic’: it is infrastructural war of the most vicious kind, waged without restraint or remorse. In the past, some Israeli politicians have demanded that Israel shut off the power (and water) supply to Gaza – for some of the international legal considerations, see Kevin Jon Heller’s careful review for Opinio Juris – but what has happened today isn’t about turning switches on or off. Here is Harriet Sherwood in the Guardian:

The power plant is finished,” said its director, Mohammed al-Sharif, signalling a new crisis for Gaza’s 1.7 million people, who were already enduring power cuts of more than 20 hours a day.

Amnesty International said the crippling of the power station amounted to “collective punishment of Palestinians”. The strike on the plant will worsen already severe problems with Gaza’s water supply, sewage treatment and power supplies to medical facilities.

“We need at least one year to repair the power plant, the turbines, the fuel tanks and the control room,” said Fathi Sheik Khalil of the Gaza energy authority. “Everything was burned.”

Since I published the original version of this post, Human Rights Watch has documented – on 10 August – the cascading effects of the strike on the power plant:

It has drastically curtailed the pumping of water to households and the treatment of sewage, both of which require electric power. It also caused hospitals, already straining to handle the surge of war casualties, to increase their reliance on precarious generators. And it has affected the food supply because the lack of power has shut off refrigerators and forced bakeries to reduce their bread production.

“If there were one attack that could be predicted to endanger the health and well-being of the greatest number of people in Gaza, hitting the territory’s sole electricity plant would be it,” said , deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Deliberately attacking the power plant would be a war crime.”…

Ribhi al-Sheikh, deputy head of the Palestine Water Authority, said the lack of electricity had idled wells – except where generators were able to provide some back-up power – as well as water treatment and desalination plants. Idling wells endangers crops that require water at the hottest time of year.

Most urban households in Gaza need electricity to pump water to rooftop tanks. Ghada Snunu, a worker for a nongovernmental organization, said on August 4 that her home in Gaza City had been without electricity since the attack on the power plant, forcing her family to buy water in jerry cans and to conserve the used household water to empty the toilets. The collapse of electricity service meant that many Gazans lacked access to the 30 liters of water that is the estimated amount needed per capita daily for drinking, cooking, hygiene and laundering, said Mahmoud Daher, head of the Gaza office of the UN World Health Organization.

This is how Israel exercises its ‘right to defend itself’ and how ‘the most moral army in the world’ is set loose on civilians.

In the case of targeted killing (see ‘Drone geographies’, DOWNLOADS tab), the same network effects obtain:

‘…by fastening on a single killing – through a ‘surgical strike’ – all the other people affected by it are removed from view. Any death causes ripple effects far beyond the immediate victim, but to those that plan and execute a targeted killing the only effects that concern them are the degradation of the terrorist or insurgent network in which the target is supposed to be implicated. Yet these strikes also, again incidentally but not accidentally, cause immense damage to the social fabric of which s/he was a part – the extended family, the local community and beyond – and the sense of loss continues to haunt countless (and uncounted) others.’

This tactic, too, has been honed by the IDF, though not exactly refined. Last year Craig Jones noted:

Since September 29th 2000, Israel has killed 438 Palestinians using the method of targeted killing. Of these, 279 were the ‘object’ of attack, meaning that Israel intentionally targeted them. The other 159 were ‘collateral damage’, chalked up to accidental or incidental consequences of targeting the other 279.

Rummaging around today, I’ve discovered another version of Sam Weber’s thesis with which I began, thanks to Jon Cogburn. It’s a poem by the late (nationalist) Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai (who died in 2000) called ‘The Diameter of the Bomb’ (translated here by Chana Bloch):

The diameter of the bomb was thirty centimeters

and the diameter of its effective range about seven meters,

with four dead and eleven wounded.

And around these, in a larger circle

of pain and time, two hospitals are scattered

and one graveyard. But the young woman

who was buried in the city she came from,

at a distance of more than a hundred kilometers,

enlarges the circle considerably,

and the solitary man mourning her death

at the distant shores of a country far across the sea

includes the entire world in the circle.

And I won’t even mention the crying of orphans

that reaches up to the throne of God and

beyond, making a circle with no end and no God.

The poem was written in 1972, and in 2006 was the inspiration for a documentary film, also called The Diameter of the Bomb, about the aftermath of a suicide bombing in Jerusalem. But its power reaches beyond place and time. And that, in case anyone is wondering, is symbolic.