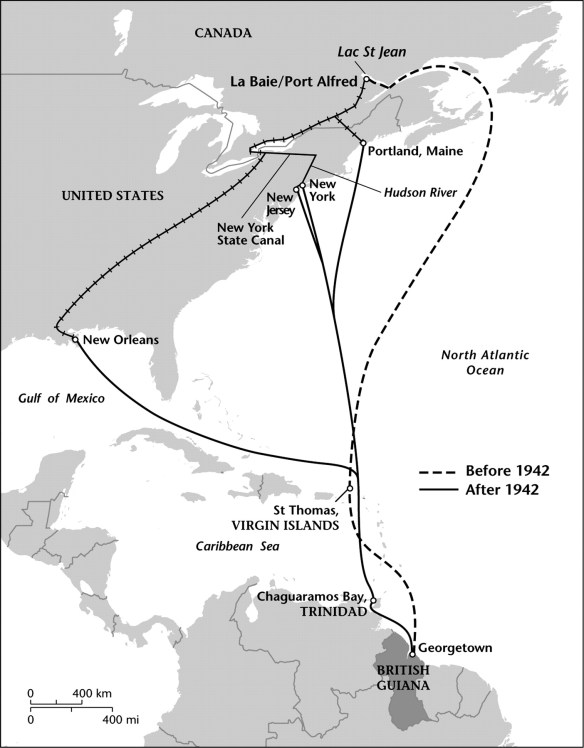

I’m working on a presentation that will turn into a long essay that may turn into a short book – one day I will learn how to write in brief! – and I thought I’d share some of the bibliographic resources I’ve been using. This is not an exhaustive list, needless to say, but I hope it will be a useful springboard for others too; I’ve tried to indicate the range of journals and sources available, and some of the key areas of contention and concern. Much of the debate on drones has focused on the supposedly covert US air campaign directed by the CIA in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas, which plainly raises vital issues of ethics, law and accountability that can also be extended to parallel campaigns in Somalia, Yemen and elsewhere. But – as I’ve tried to show in my own work – this should not allow the overt air war in Afghanistan to escape scrutiny. Here the operational questions often become more complex because these platforms are integrated into extended networks in which surveillance is conducted by remote operators but the strikes may be executed by conventional aircraft: the geography of the kill-chain is crucial. For this, I’ve been drawing on a series of USAF publications and presentations.

But the focus on the US distract should not distract attention from the rapid expansion of remote capabilities by other militaries, including (as the listing below indicates) Israel, where the IDF developed a series of protocols for extra-judicial killing (assassination) long before the USAF or the CIA.

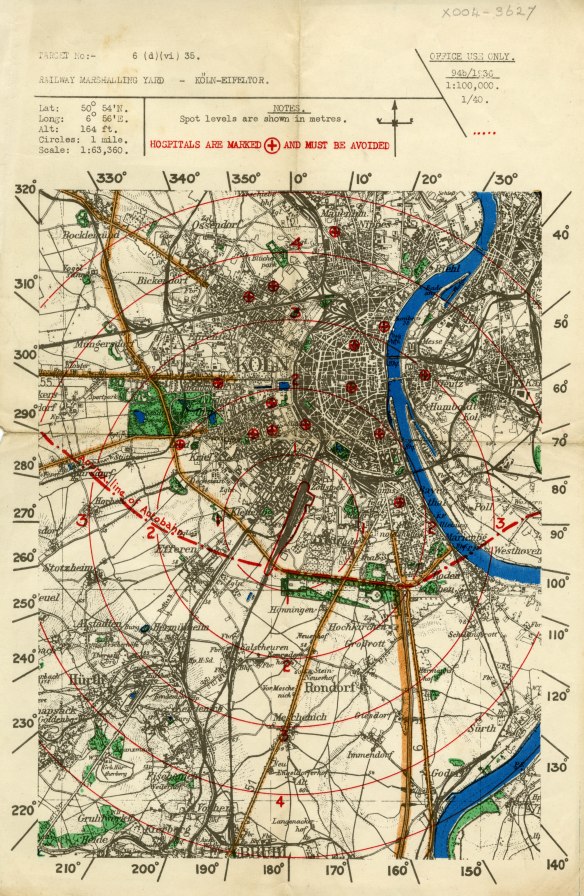

There are also important historical precedents to consider: the use of air power in colonial counterinsurgency operations, particularly by the British in Mesopotamia (Iraq), the North West frontier of India and Palestine, and the emergence of key elements of today’s remote operations in the Second World War and, in particular, during the US air wars over Indochina. For the former, the work of David Omissi, Air power and colonial control: the Royal Air Force 1919-1939 (1990), Priya Satia, Spies in Arabia: the Great war and the cultural foundations of Britain’s covert empire in the Middle east (2008) [see also her essay on ‘The defense of inhumanity: air control in Iraq and the British idea of Arabia’, American historical review 11 (2006)], and Andrew Roe, Waging war in Waziristan (2010) are key sources. For the latter, see my ‘Lines of descent’ (DOWNLOADS tab).

There are some significant gaps in the listings that follow. There is already a book that gives a pilot’s view of these remote missions, Matt Martin‘s Predator, and there’s no shortage of media interviews with (American) crewmembers, usually based at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada. But, with rare exceptions, the media have shown little interest in documenting the victims of drone strikes, apart from (contentious) estimates of their numbers and claims of ‘high-value targets’ being killed. For preliminary assessments of the distortions of media coverage, see Timothy Jones, Penelope Sheets and Charles Rowling, ‘Differential news framing of unmanned aerial drones: efficient and effective or illegal and inhumane’ (APSA, 2011: available via ssrn.com) and Tara McKelvey in the Columbia Journalism Review (listed below).

There are virtually no ethnographies of life (and death) under the drones: Shahzad Bashir and Robert Crews have recently curated some interesting essays on daily life in the Afghanistan-Pakistan borderlands, but the title Under the drones (Harvard University Press, 2012) is opportunistic. The editors write of their desire to ‘illuminate aspects of the rich social and cultural worlds that are opaque to cameras mounted on drones flying many thousands of feet above this terrain’ – an admirable project – but not a single contributor illuminates the impact of the drone wars on those worlds. There are some sharp questions about the missing ethnographies of death – unlike the surgical dissections of sovereignty – in Anthony Allen Marcus, Ananthakrishnan Aiyer and Kirk Dombroiwski, ‘Droning on: the rise of the machines’, Dialectical Anthropology 36 (2012) 105. Some of the best reportage on the effects of drone strikes in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan comes from CIVIC, but its most recent report on Civilian Harm and Conflict in Northwest Pakistan was published in October 2010 (this also documents the suffering caused by Pakistan military action), though there are some updates on its blog (listed below).

Noor Behram has provided an unforgettable photographic record of the aftermath of drone attacks in the same area (200 images from 27 sites) that formed a centrepiece for the Gaming Waziristan exhibition staged in the UK, the US and Pakistan in 2011: for online galleries see here and here. And other visual/video artists have not been slow to reflect on these new modalities of killing: see, for example, John Butler’s The ethical governor (available on YouTube and vimeo) or Omer Fast’s Five thousand feet is the best (in which a white American family is killed in a Predator attack).

In addition, Jordan Crandall has a performance work, ‘philosophical theatre’, called Unmanned at Eyebeam that I’d love to see…. It involves the crash of a drone in a suburban backyard in the American southwest.

If you think I’ve missed something that ought to be included, please let me know.

Note: Most militaries disdain the term ‘drones’ since these aircraft are piloted, and prefer ‘Unmanned Aerial Vehicles’ (UAVs) or ‘Unmanned Aerial Systems’ (UAS) or ‘Remotely Piloted Aircraft’ (RPAs). Most of the listings below are concerned with the use of these platforms to conduct air strikes; smaller drones are also deployed by ground forces for surveillance and no doubt they too will soon be able to carry out strikes.

Nick Turse and Tom Engelhardt, Terminator planet: the first history of drone warfare 2001-2050 (Dispatch Books, 2012) – a sharp analysis of drone wars, past, present and future, culled from the regular reports of the TomDispatch principals; also available as an e-book

Nick Turse and Tom Engelhardt, Terminator planet: the first history of drone warfare 2001-2050 (Dispatch Books, 2012) – a sharp analysis of drone wars, past, present and future, culled from the regular reports of the TomDispatch principals; also available as an e-book

Medea Benjamin, Drone warfare: killing by remote control (OR Books, 2012)– a passionate critique from the co-founder of Code Pink and Global Exchange that also details the rise of activist campaigns against drone warfare; also available as an e-book

Matt Martin and Charles Sasser, Predator: the remote-control air war over Iraq and Afghanistan: a pilot’s story (Zenith Press, 2010) – most of the commentary on drones is concerned with covert campaigns waged by the CIA (with JSOC), but this is an account of USAF operations that also deserve close scrutiny….

Peter Singer, Wired for war: the robotics revolution and conflict in the 21st century (Penguin, 2009) – about much more than drones, but Singer has a series of perceptive observations about them scattered throughout the book.

Drone Wars UK – focuses on the British use of drones, but also includes wider commentary and information and a useful Drone Wars briefing pdf by Chris Cole [see also Convenient Killing below]

Drones Watch – advertised as ‘a coalition campaign to monitor and regulate drone use’

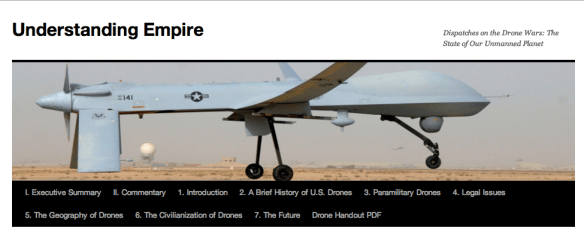

Understanding Empire – ‘dispatches on the drone wars: the state of our unmanned planet’ – a brilliant news aggregating source with commentary too

Our bombs – created by Neil Halloran ‘a website and documentary film that looks at the human cost and strategic implications of U.S. air strikes’, including an ‘air strike tracker’ from 9/11 through to January 2011

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism – a not-for-profit organisation based at City University, London, that provides (among many other things) a stream of indispensable reports, investigations and critical commentary on ‘the covert war on terror’ in Pakistan, Somali and Yemen

The #drones daily – what it says: news and commentary updated daily

The Long War Journal – Bill Roggio’s site, politically distant from the sources above, but providess useful charts, maps and reports on covert US air campaigns in Pakistan and Yemen

New America Foundation – the Year of the Drone, mapping and reporting on US drone strikes in Pakistan 2004-2012 (and continuing): but its estimates of civilian casualties (in particular) have been sharply criticised by the BIJ here.

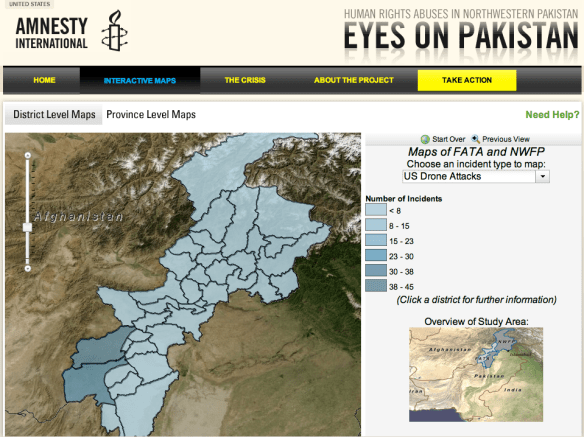

Also on Pakistan, Amnesty International has ‘Eyes on Pakistan’, focusing on human rights abuses in FATA, including maps of drone strikes, through 2009, while CIVIC (Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict) has a field blog that provides reports on war victims in Pakistan (and elsewhere)

Although (too) many of these are behind a pay-wall, I’ve tried to list publically accessible versions wherever possible. Please don’t assume that inclusion means agreement!

M.W. Aslam, ‘A critical evaluation of American drone strikes in Pakistan: legality, legitimacy and prudence’, Critical studies on terrorism 4 (2011) 313-29

Chris Cole, Mary Dobbing and Amy Hailwood, Convenient killing: Armed drones and the ‘Playstation’ mentality available here

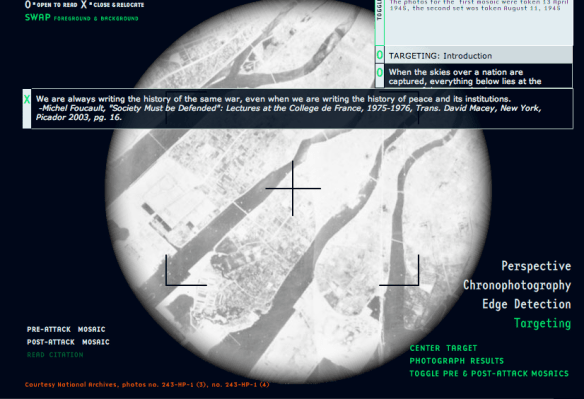

Jordan Crandall, ‘Ontologies of the wayward drone: a salvage operation’, Theory beyond the codes (2011)available here

Aliya Robin Deri, ‘“Costless war”: American and Pakistani reactions to the US drone war’, Intersect 5 (2011) available here

Christian Enemark, ‘Drones over Pakistan: secrecy, ethics and counterinsurgency’, Asian Security 7 (3) (2011) 218-37

Keith Feldman, ‘Empire’s verticality: the Af/Pak frontier, visual culture and racialization from above’, Comparative American Studies 9 (4) (2011) 325-41

Jenny Garand, ‘Robotic warfare in Afghanistan and Pakistan’ (December 2010) (Medical Association for the Prevention of War, Australia) available here

Derek Gregory, ‘From a view to a kill: Drones and late modern war’, Theory, culture and society 28 (7-8) (2011) 188-215 (see DOWNLOADS tab)

Derek Gregory, ‘The everywhere war’, Geographical Journal 177 (2011) 238-250

Derek Gregory, ‘Lines of descent’, Open Democracy, 2011 (see DOWNLOADS tab)

Leila Hudson, Colin Owens, Matt Flannes, ‘Drone warfare: blowback from the New American way of war’, Middle East Policy 18 92011) 122-132

Human Rights Watch, Precisely wrong: Gaza civilians killed by Israeli drone-launched missiles (2009)

David Jaeger and Zahra Siddique, ‘Are drone strikes effective in Afghanistan and Pakistan? On the dynamics of violence between the United States and the Taliban’ (Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, Discussion Paper 6262, December 2011) (available via ssrn.com)

Jake Kosek, ‘Ecologies of empire: on the new uses of the honeybee’, Cultural anthropology 25 (4) (2010) 650-78 (see pp. 666 on)

Katrina Laygo, Thomas Gillespie, Noel Rayo and Erin Garcia, ‘Drone bombings in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas: Remote sensing applications for security monitoring’, Journal of Geographic Information Systems 4 (2012) 136-41

Jane Mayer, ‘The Predator War’, New Yorker, 26 October 2009

Tara McKelvey, ‘Covering Obama’s Secret War’, Columbia Journalism Review, May/June 2011

Avery Plaw, Matthew Fricker and Brian Glyn Williams, ‘Practice makes Perfect? The changing civilian toll of CIA drone strikes in Pakistan’, Perspectives on terrorism 5 (506) (December 2011)

Lambèr Royakkers, Rinie van Est, ‘The cubicle warrior: the marionette of digitalized warfare’, Ethics & Information Technology 12 (2010) 289-96

Noel Sharkey, ‘The automation and proliferation of military drones and the protection of civilians’, Law, innovation and technology 3 (2) (2011) 229-240

Ian Shaw, The spatial politics of drone warfare (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Arizona, 2011) available via the university’s open repository here

Ian Shaw and Majed Akhter, ‘The unbearable humanness of drone warfare in FATA, Pakistan’, Antipode (2011) [Early View]

Jeffrey Sluka, ‘Death from above: UAVs and losing hearts and minds’, Military Review (May-June 2011) 70-76

Bradley Strawser, ‘Moral Predators: the duty to employ uninhabited aerial vehicles’, Journal of military ethics 9 (2010) 342-68

Tyler Wall and Torin Monahan, ‘Surveillance and violence from afar: the politics of drones and liminal security-scapes’, Theoretical criminology 15 (2011) 239-54

Alison Williams, ‘Enabling persistent presence? Performing the embodied geopolitics of the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle assemblage’, Political Geography [early view] doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.08.002

Brian Glyn Williams, ‘The CIA’s covert Predator drone war in Pakistan, 2004-20010: the history of an assassination campaign’, Studies in conflict and terrorism 3 (2010) 871-92

There is also a rapidly developing literature on international law, lawfare and targeted killing that integrates the use of drones into its discussions:

Philip Alston, ‘The CIA and targeted killings beyond borders’, New York University School of Law Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series, Working Paper 11-64 (2011)

Kenneth Anderson, ‘Targeted killing and drone warfare: how we came to debate whether there is a “legal geography of war”, American University, Washington College of aw Research Paper 2011-16 (available via ssrn.com) [there are multiple papers by Anderson on these issues, usually available via ssrn.com]

Jack Beard, ‘Law and war in the virtual era’, American Journal of International Law 103 (2009) 409-445

O. Ben-Naftali, and Karen Michaeli, ‘We must not make a scarecrow of the law: a legal analysis of the Israeli policy of targeted killings’, Cornell International Law Journal 36 (2003)

Laurie Blank, ‘After “Top Gun”: How drone strikes impact the law of war’, University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law (2012)

Amitai Etzioni, ‘Unmanned Aircraft Systems: the legal and moral case’, Joint Forces Quarterly (57) (2010)

Neve Gordon, ‘Rationalising extra-judicial executions: the Israeli press and the legitimisation of abuse’, International journal of human rights 8 (2004) 305-24

Kyle Grayson, ‘Six theses on targeted killing’, Politics 32 (2012) 120-8

Kyle Grayson, ‘The ambivalence of assassination: biopolitics, culture and political violence’, Security dialogue 43 (2012) 25-41

Lisa Hajjar, ‘Lawfare and targeted killing: developments in the Israeli and US contexts’, Jadaliyya , 15 January 2012 here.

Chris Jenks, ‘Law from above: unmanned aerial systems, use of force and the law of armed conflict’, North Dakota Law Review 85 (2009) 649-671 [available via ssrn.com]

Sarah Kreps and John Kaag, ‘The use of unmanned aerial vehicles in combat: a legal and ethical analysis’, Polity (2012) 1-1=26 [early view]

Michael Lewis, ‘Drones and the boundaries of the battlefield’, Texas International Law Journal (2012) [available via via ssrn.com]

Nils Melzer, Targeted Killing in International Law (Oxford University Press, 2009)

Mary Ellen O’Connell, ‘Seductive drones: learning from a decade of lethal operations’, Journal of law, information and science [special edition: The law of unmanned vehicles] [available via ssrn.com]

Mary Ellen O’Connell, ‘The international law of drones’, American Society of International Law Insights 14 (36) November 2010

Mary Ellen O’Connell, ‘Unlawful killing with combat drones: a case study of Pakistan, 2004-9), Notre Dame Law School, Legal Studies Research paper 09-43 (2009) available via ssrn.com

Andrew Orr, ‘Unmanned, unprecedented and unresolved: the status of American drone strikes in Pakistan under international law’, Cornell International Law Journal 44 (2011) 729-752 [available here ]

Joseph Pugliese, ‘Prosthetics of law and the anomic violence of drones’, Griffith Law Review 20 (2011) 931-61

Noel Sharkey, ‘Saying “No!” to lethal autonomous targeting’, Journal of military ethics 9 (2010) 369-83

Ryan Vogel, ‘Drone warfare and the law of armed conflict’, available via ssrn.com

Eyal Weizman, ‘Thanato-tactics’, in in Adi Ophir, Michal Givoni and Sari Hanafi (eds), The power of inclusive exclusion: anatomy of Israeli rule in the occupied Palestinian territories (New York: Zone Books, 2009) pp. 543-573 and in Patricia Clough and Craig Willse (eds) Beyond biopolitics: essays on the government of life and death (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011)

I suspect that one of the imaginative devices that enables publics in the global North to accept their own militaries bombing from the air – apart from a profound lack of imagination – turns on the body itself. In one direction, they congratulate themselves that suicide bombing is foreign to their traditions of war in part, I think, because it allows no escape from the corporeality of bombing: the body of the bomber carries the bomb. In the other direction, they congratulate themselves on their restraint: after Hiroshima and Nagasaki they have not resorted to nuclear bombs that, at the limit, vaporize bodies (though they also leave countless other bodies broken and disfigured from the blast or sick from radiation). (In his meditation On Suicide bombing Talal Asad is very instructive on the horror generated by ‘the dissolution of the human body’ (see pp. 76-92)).

I suspect that one of the imaginative devices that enables publics in the global North to accept their own militaries bombing from the air – apart from a profound lack of imagination – turns on the body itself. In one direction, they congratulate themselves that suicide bombing is foreign to their traditions of war in part, I think, because it allows no escape from the corporeality of bombing: the body of the bomber carries the bomb. In the other direction, they congratulate themselves on their restraint: after Hiroshima and Nagasaki they have not resorted to nuclear bombs that, at the limit, vaporize bodies (though they also leave countless other bodies broken and disfigured from the blast or sick from radiation). (In his meditation On Suicide bombing Talal Asad is very instructive on the horror generated by ‘the dissolution of the human body’ (see pp. 76-92)).

![Saucepans into Spitfires [Imperial War Museum]](https://geographicalimaginations.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/large.jpg?w=584)