Part of my histories/geographies of bombing project involves addressing the work of visual artists who have attempted to render the violence of bombing not from below but from above. There are many powerful works that show the horror of bomb-sites and broken bodies, and I’m not uninterested in them; but to convey the violence of bombing in advance, so to speak, demands a much more exacting political aesthetic.

Part of my histories/geographies of bombing project involves addressing the work of visual artists who have attempted to render the violence of bombing not from below but from above. There are many powerful works that show the horror of bomb-sites and broken bodies, and I’m not uninterested in them; but to convey the violence of bombing in advance, so to speak, demands a much more exacting political aesthetic.

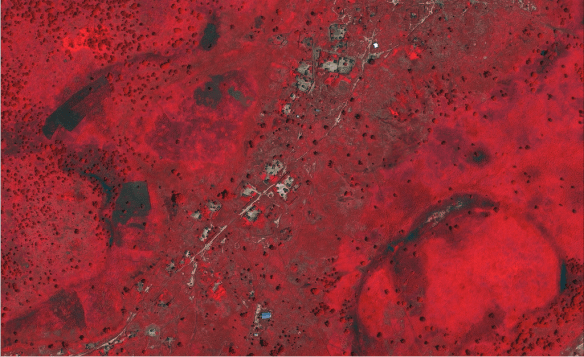

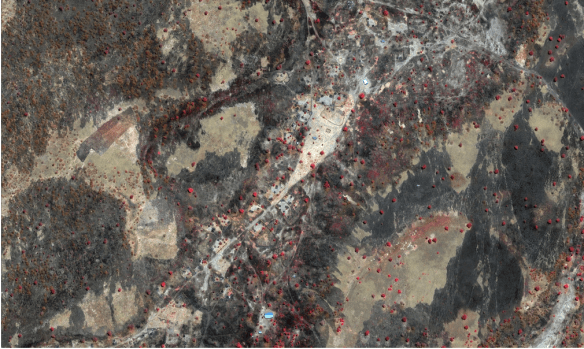

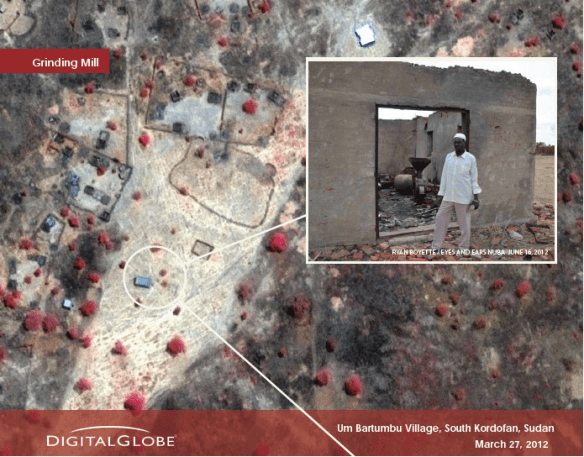

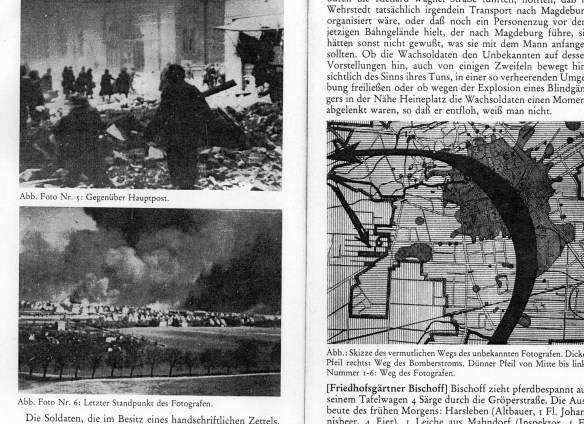

This vantage point matters because that is typically how those outside the conflict zone see air strikes conducted in their name. During the Second World War the British press and newsreels showed the firebombing of German cities from above (in contrast, of course, to their coverage of the Blitz), and this facilitated the representation of area bombing as ‘precision bombing’ (in contrast, again, to their coverage of the Blitz); in the weeks following the Allied invasion of Europe American and British journalists swept across the continent with the advancing armies and were stunned by what they saw on the ground in Cologne, Hamburg and other cities.

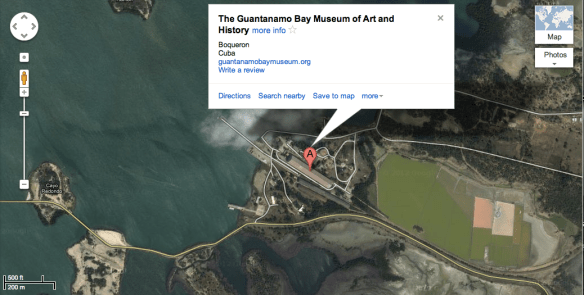

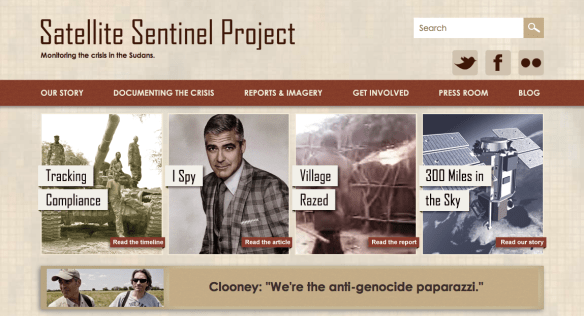

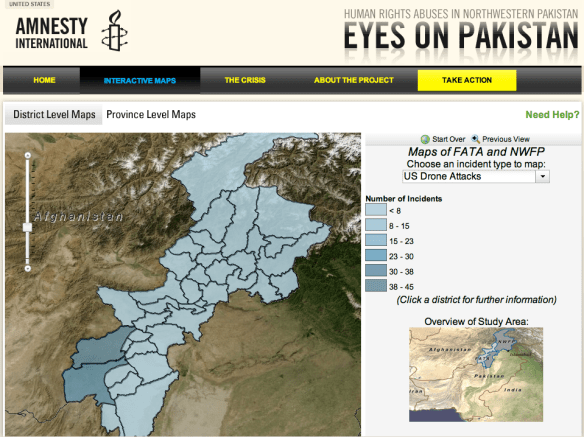

In the weeks before the US-led invasion of Iraq, Baghdad was repeatedly represented, in graphics, aerial and satellite photographs, and online interactives, as nothing more than a series of targets: then, as I showed in The colonial present, in the very week that Saddam’s statue was toppled, maps appeared showing Baghdad for the first time as a series of neighbourhoods inhabited not by tyrants, terrorists and torturers but by people like you and me. If those images had been the dominant representation in the weeks and months before the attack, how many more would have been on streets around the world to try to prevent the invasion?

We can’t possibly know: but we surely do know that by the time we imaginatively crouch under the bombs and empathise with their victims it’s too late.

There is an appropriately long arc of work to consider, including artworks by Martin Dammann [the Überdeutschland series], Hanaa Malallah, Joyce Kozloff [‘Targets’], Raquel Maulwurf, Gerhard Richter [Atlas], and Nurit Gur-Lavy. I’ll post about some of the artworks later, and if anyone knows of others I ought to consider, I’d be very grateful to know about them. But my very first engagement with these issues was through the work of ellen o’Hara slavick, now Distinguished Professor of Art at UNC Chapel Hill, and a project that was eventually called Bomb after Bomb: a violent cartography (she originally intended to call it ‘Everywhere the United States has bombed‘). More on the series of 60-plus images and related projects here, here, here and here (the last is on Hiroshima). The book version (Charta, 2007) comes with additional essays by Cathy Lutz, Carol Mavor and the late Howard Zinn.

There is an appropriately long arc of work to consider, including artworks by Martin Dammann [the Überdeutschland series], Hanaa Malallah, Joyce Kozloff [‘Targets’], Raquel Maulwurf, Gerhard Richter [Atlas], and Nurit Gur-Lavy. I’ll post about some of the artworks later, and if anyone knows of others I ought to consider, I’d be very grateful to know about them. But my very first engagement with these issues was through the work of ellen o’Hara slavick, now Distinguished Professor of Art at UNC Chapel Hill, and a project that was eventually called Bomb after Bomb: a violent cartography (she originally intended to call it ‘Everywhere the United States has bombed‘). More on the series of 60-plus images and related projects here, here, here and here (the last is on Hiroshima). The book version (Charta, 2007) comes with additional essays by Cathy Lutz, Carol Mavor and the late Howard Zinn.

In “Doors into nowhere” (DOWNLOADS tab) I glossed elin’s project like this:

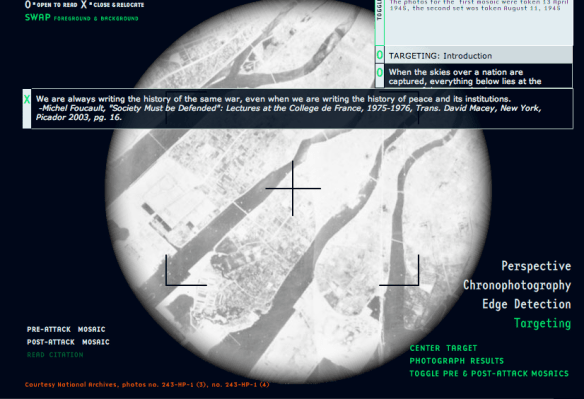

She adopts an aerial view – the position of the bombers – in order to stage and to subvert the power of aerial mastery. The drawings are made beautiful ‘to seduce the viewer’, she says, to draw them in to the deadly embrace of the image only to have their pleasure disrupted when they take a closer look. ‘Like an Impressionist or Pointillist painting,’ slavick explains, ‘I wish for the viewer to be captured by the colors and lost in the patterns and then to have their optical pleasure interrupted by the very real dots or bombs that make up the painting.’

There’s much more to her work than this, as I try to show in my commentary, but what interests me here is that disturbing cascade that runs from beauty through seduction to pleasure. There is a considerable literature on the dangers of aestheticizing violence, but plainly elin’s work is, as I said at the start, much more exacting than this.

Over at Books & Ideas Vanina Géré now has a short but pointed essay on ‘Artistic beauty as a political weapon’ that addresses these issues in helpful ways. Political art, she writes, is always threatened by the prospect that

‘the political message will not get through because of the work’s retinal character — in other words, because the work is appreciated primarily for its formal qualities. If political art is often considered lacking in formal efficacy, formally remarkable works are often deemed lacking in political efficacy: too much plastic beauty risks making politics a topic like any other. In grappling with this demanding question, some artists have chosen to accentuate their works’ capacity for formal seduction by springing visual traps, placing viewers before realities that they did not expected to encounter in the rarefied air of a museum or a gallery.’

This is a particularly sharp dilemma for political representations of bombing, since the practice such artworks seek to apprehend and dislocate is itself ‘retinal’, formal: it is made possible by a series of performative abstractions that strip away content. Cities as places where people live are reduced to co-ordinates, targets, pixels, flares of flight. Géré doesn’t discuss slavick’s work, but her commentary on Brigitte Zieger‘s Eye Dust series speaks directly to the more general issues surrounding political art and military violence:

‘Using glitter eye shadow to draw clouds rising from explosions, the series creates a dialectical movement in which what we see (the makeup) hides what is (a face), yet nevertheless sheds light on a form of everyday violence. At the same time, these sumptuously executed images, which gently shine, entice the viewer to become increasingly fascinated with images of violence. Zieger’s work, by outrageously exploiting its own aesthetic quality in order to offer a critical perspective on representations and manifestations of military violence, demonstrates by this very token that behind every effort to impose beauty lurks a hidden form of violence. Beauty collaborates with politics, as the very concept of beauty is (in part) political. The challenge of such work lies in the precarious balance between the two.’

For Zieger’s own account of her work on war, violence and intimacy see this short video: