Both Stuart Elden and I have drawn attention to Eyal Weizman‘s Forensic Architecture project – sketched in outline in his The least of all possible evils and the subject of his Society & Space lecture – but for those who want more…

Eyal Weizman (L) and Steve Graham (R) in the occupied West Bank [Derek Gregory]

Michael Schapira and Carla Hung interview Eyal in “Thinking the Present” at Full Stop. Here’s an extract where Eyal summarises his project:

‘Forensic Architecture is grounded in both field-work and forum-work; fields are the sites of investigation and analysis and forums the political spaces in which analysis is presented and contested. Each of theses sites presents a host of architectural and political problems.

In fields, lets say starting with Territories, I attempted to engage a kind of “archeology” of present conditions as they could be read, or misread, in architecture. This archeology is not always undertaken by direct contact with the materiality under analysis, but with images of it. The spaces that we debate, analyze, or make claims on behalf of, are very often media products. Similarly, drawing a map includes synthesizing satellite and aerial images as well as images from the ground. Some images are created by optics and some by different sensors that register spectrums beyond the visible. One needs sensors to read sensors.

So this is a kind of archaeology of spaces as they are captured in these different forms of capture and registration. You read details, speckles, pixels and patterns, connect them to larger forces, or at least you understand the impossibility of doing so, often noting paradoxes and misrepresentations. We have done this very close reading of aerial images of colonies in the West Bank, we have read almost all elements from architectural through infrastructural archaeological to horticultural ones visible in these images as a set of tools in a battlefield.

Then there is the forum: a site of interpretation, verification, argumentation and decision. International courtrooms, tribunals, and human rights councils are of course the most obvious sites of contemporary forensics. But there are other political and professional forums.

Each forum is different. The third component of forensics, beyond the architectural and aesthetic, is what you need in order to stand between that “thing” and the forum: an “interpreter.” In ancient Rome it would be the orator; in our days it is perhaps the scientist, or the architect, or the geographer — the “expert witness” that translates from the language of space to the language of the forum. This definition of forensics might help expand the meaning of the term from the legal context to all sorts of others. Politics, as it is undertaken, around the problems of space and its interpretations, is a “forensic politics” as far I understand it.

Each of the multiple political and legal forums in use today — professional, scientific, parliamentary or legal — operates by a different set of protocols of representation and debate. They each have another frame of analysis. Each embodies dominant political forces and ideologies — that is to say that each instrumentalizes forensics as a part of a different ideological structure. In the turbulence of a changing world, there are also informal, subversive and ad-hoc and crisis forms of gathering: pop-up assemblies of protest and revolt in which the debate of financial, architectural (the housing or mortgage crisis), and geopolitical issues are often articulated.

Forensic architecture should thus be understood not only as dealing with the interpretation of past events as they register in spatial products, but about the construction of new forums. It is both an act of claim-making on the bases of spatial research and potentially an act of forum-building.’

Eyal edited a special section of Cabinet magazine (#43) on “Forensics”, and there’s an early lecture (May 2010) on ‘Forensic Architecture’ here and an image-rich conversation with Open Democracy’s wonderful Rosemary Belcher on ‘Forensic Architecture and the speech of things’ here.

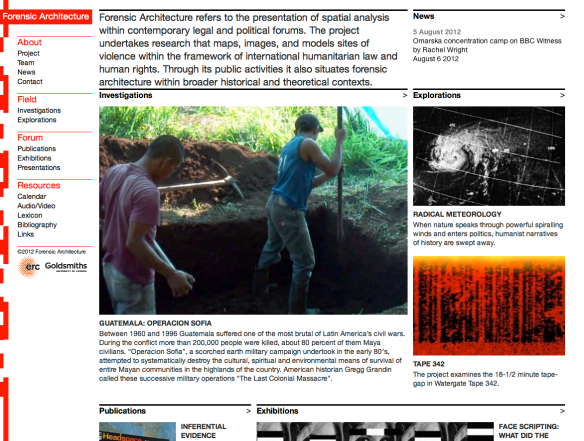

There is also a truly excellent website for the project, which is hosted by the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths University of London within the Department of Visual Cultures.

Highlights for me include:

under Investigations, Forensic Oceanography (probing the deaths of more than 1500 people fleeing Libya across the Mediterranean in 2011, including a downloadable report), a report on the effects of airborne White Phosphorus munitions in densely populated urban areas like Gaza, and a challenging (I imagine preliminary) commentary on ways of recording and investigating deaths from drone strikes in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas:

‘The near complete prohibition upon carrying recording equipment into this region of Pakistan, coupled with the non-existence of local maps has made the task of locating and representing the sites and consequences of drone attacks extremely difficult. This inability to produce corroborating evidence has, in turn, severely hampered the pursuit of legal claims. Forensic Architecture is working with human rights and legal justice organisations in both Pakistan and the UK to develop an alternate mapping system that can meet the unique challenges posed by the dilemma of creating accurate maps without relying upon technologies of exact recording, but only upon haptic techniques of observation and recall, or what has been called “transparency cameras”. This system needs to be matched, in turn, with a post-production methodology of transcription and interpretation of recollection data. Survivors and witnesses of drone strikes are typically brought to safe zones outside of Northwest Pakistan in cities such as Islamabad, where they are interviewed by legal staff and their stories cross-referenced and collated.’

under Explorations, a sketch of what the project calls ‘Video-to-space analysis’ derived from the recognition that ‘remote controlled vision machines (satellites and drones) and the handheld devices of citizen journalists working independently of news-desks marks a shift in the ways in which human rights violations will increasingly be charted and mapped and the ways in which the spaces of conflict themselves will increasingly become known or offer up information.’

under Presentations, a record of a seminar in March 2012 with Bruno Latour who comments on a series of investigations (Paulo Tavares, “The Earth-Political”; Nabil Ahmed, “Radical Meteorology'”; John Palmesino, “North – The architecture of a territory open on all sides”): ‘Forensics is the production of public proof’ (with some interesting asides about ‘geopolitics’ and what he calls ‘politics of the earth’), and a tantalising glimpse of a conference presentation by Susan Schuppli under the title ‘War Dialling: Image Transmissions from Saigon’, which discussed the modalities through which, on June 8 1972, ‘a portable picture transmitter, took 14 minutes to relay a series of audio signals from Saigon to Tokyo and then onwards to the US where they were reassembled into a B&W image to reveal a young Vietnamese girl [Kim Phúc] running out of the inferno of an erroneous napalm attack.’

These reflect my own preoccupations, but there’s lots more – it’s a treasure trove of imagination and insight. Oh – and a reading list.