My earlier post about War and distance emphasised the historical significance of the telegraph because it allowed information to be transmitted without the movement of messengers, but these systems obviously required the installation and maintenance of physical infrastructure. Still, in August 1870 the Montreal Gazette was already anticipating the vital role of the new communications network in the emergence of frictionless war:

‘Modern science has brought each dependency of the Empire within swift reach of the controlling centre. The communications are ever open while the command of the sea remains… There converge in London lines of telegraphic intelligence … [and] it needs but a faint tinkle from the mechanism to despatch a compelling armament to any whither it may be called… The old principle of maintaining permanent garrisons round the world suited very well an age anterior to that of steam and electricity. It has passed out of date with the stage coach and the lumbering sailing transport.’

The Gazette was ahead of itself; even today, the United States garrisons the planet, and waging war over long distances still usually involves the physical movement of troops and supplies (the cardinal exception is cyberwar: more on that later). Martin van Creveld‘s Supplying War (1977; 2004) suggested that ‘logistics make up as much as nine tenths of the business of war, and … the mathematical problems involved in calculating the movements and supply of armies are, to quote Napoleon, not unworthy of a Leibnitz or a Newton…. From time immemorial questions of supply have gone far to govern the geography of military operations.’

The Gazette was ahead of itself; even today, the United States garrisons the planet, and waging war over long distances still usually involves the physical movement of troops and supplies (the cardinal exception is cyberwar: more on that later). Martin van Creveld‘s Supplying War (1977; 2004) suggested that ‘logistics make up as much as nine tenths of the business of war, and … the mathematical problems involved in calculating the movements and supply of armies are, to quote Napoleon, not unworthy of a Leibnitz or a Newton…. From time immemorial questions of supply have gone far to govern the geography of military operations.’

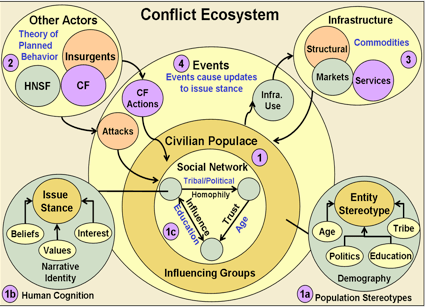

Halvard Buhaug and Nils Petter Gleditsch reckon that this is still the case; they concluded (in 2006) that ‘The main factor to limit the military reach of armed force is not the range of the artillery or the combat radius of attack planes. The largest obstacles to remote military operations relate to transportation and logistics.’

Stores for the Prussian siege of Paris at Cologne station

There is a contentious backstory to Creveld’s main thesis – that before 1914 ‘armies could only be fed as long as they kept moving’, foraging (and pillaging) as they went – which has sparked an ongoing debate about the logistics of early modern siege warfare and pitched battle. But by the time of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) it was already clear – to the Prussians at least – that the railway had transformed the business of war. ‘We are so convinced of the advantage of having the initiative in war operations that we prefer the building of railways to that of fortresses,’ Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke had declared: ‘One more railway crossing the country means two days’ difference in gathering an army, and it advances operations just as much.’

Armand Mattelart discusses the strategic implications of this in The invention of communication (1996, pp. 198-208), but the role of the railway in supplying modern war has been described in great detail by Christian Wolmar. He contrasts the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 – ‘the last significant conflict before the invention of railways’ – which was over in less than a day, leaving 40,000 men dead, with the Battle of Verdun, ‘which lasted most of 1916’ and resulted in 700,000 dead and wounded soldiers. The crucial difference, according to Wolmar, was the railway, that ‘engine of war’, and here – as elsewhere – the chronology is complicated. The Franco-Prussian War was indeed a significant waystation, but events didn’t work out quite as von Moltke had envisaged. The railways certainly speeded the mobilization of Prussian troops but, as Wolmar explains,

Armand Mattelart discusses the strategic implications of this in The invention of communication (1996, pp. 198-208), but the role of the railway in supplying modern war has been described in great detail by Christian Wolmar. He contrasts the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 – ‘the last significant conflict before the invention of railways’ – which was over in less than a day, leaving 40,000 men dead, with the Battle of Verdun, ‘which lasted most of 1916’ and resulted in 700,000 dead and wounded soldiers. The crucial difference, according to Wolmar, was the railway, that ‘engine of war’, and here – as elsewhere – the chronology is complicated. The Franco-Prussian War was indeed a significant waystation, but events didn’t work out quite as von Moltke had envisaged. The railways certainly speeded the mobilization of Prussian troops but, as Wolmar explains,

‘The Germans had expected to fight the war on or around the border and had even prepared contingency plans to surrender much of the Rhineland, whereas in fact they found that, thanks to French incompetence, they were soon heading for the capital. The war, consequently, took place on French rather than German territory, much to the surprise of Moltke, upsetting his transportation plans, which had relied on using Prussia’s own railways. The distance between the front and the Prussian railheads soon became too great to allow for effective distribution, and supplies of food for both men and horses came from foraging and purchases of local produce.’

Back to a world of foraging and laying siege. The decisive moment was probably (as Wolmar’s vignette abut Verdun suggests) the First World War of 1914-1918. Even as late as 1870, Creveld argues, ammunition formed less than 1 per cent of all supplies, whereas in the first months of the First World War the proportion of ammunition to other supplies was reversed:

‘‘To a far greater extent than in the eighteenth century, strategy became an appendix of logistics. The products of the machine – shells, bullets, fuel, sophisticated engineering materials – had finally superseded those of the field as the main items consumed by armies, with the result that warfare, this time shackled by immense networks of tangled umbilical cords, froze and turned into a process of mutual slaughter on a scale so vast as to stagger the imagination.’

Empty shell casings and ammunition boxes, a sample of the ammunition used by the British Army in the bombardment of Fricourt on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916 [Australian War Memorial, AWM H08331]

In August 1914, for example, British field guns had a total of 1,000 shells available at or approaching the front lines; by June 1916 each eighteen-pound gun had 1,000 shells stockpiled at its firing position, and by 1918 Britain had over 10,000 guns, howitzers and trench mortars in the field. An elaborate system of light ‘trench railways’ was constructed on the Western Front to transport the ammunition to the front lines. (A note for afficionados of crime fiction: see Andrew Martin’s The Somme stations [2011]).

Supply of munitions on the Western Front

It’s that toxic combination of movement and stasis that was (and remains) so shattering. As Modris Eksteins described it in Rites of Spring: The Great War and the birth of the modern age (1989),

‘The war had begun with movement, movement of men and material on a scale never before witnessed in history. Across Europe approximately six million men received orders in early August [1914] and began to move… [And them for two years, 1916 and 1917] this new warfare that cost millions of men their lives … moved the front line at most a mile or so in either direction.’

And it was locked down in part because men and material continued to be moved up to the front lines.

Now Creveld’s argument was limited to ground forces – he said nothing about sea power or air power – and was confined to war in Europe, and these are significant caveats. During the Second World War the Battle for the Atlantic was crucial. Churchill famously declared that ‘Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea, or in the air, depended ultimately on its outcome.’ There is a rich literature on convoys and submarine attacks that I’m only just beginning to explore. Although the Allies lost 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships, however, more than 99 per cent of ships sailing to and from the beleaguered British Isles survived the crossing.

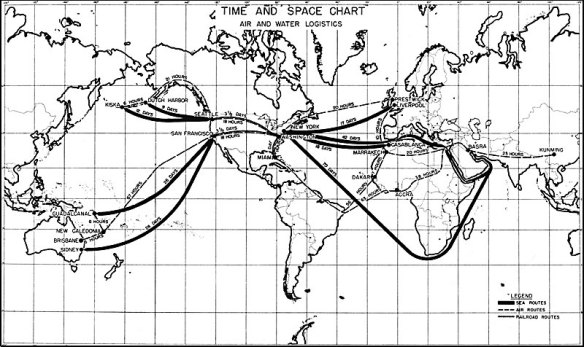

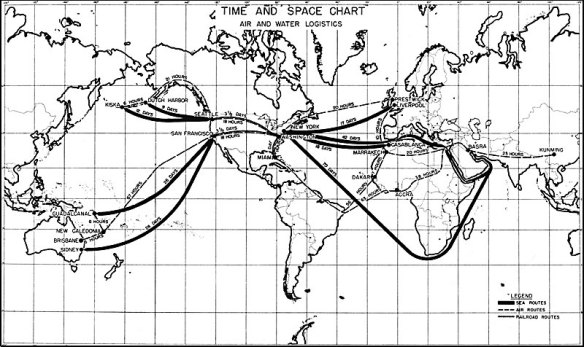

If we enlarge the scale to consider the supply of war materials beyond the European theatre – as in this graphic which shows US global logistics during the Second World War – then the complexity and vulnerability of the supply chain becomes even clearer.

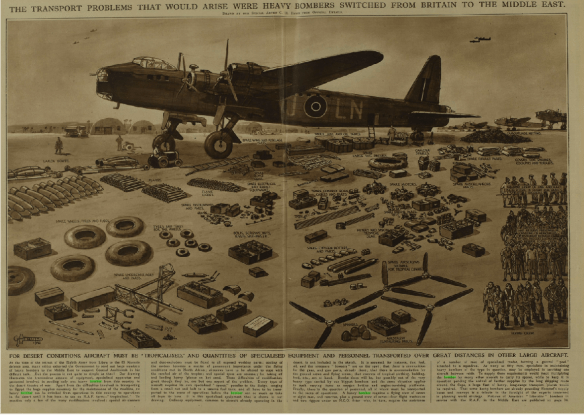

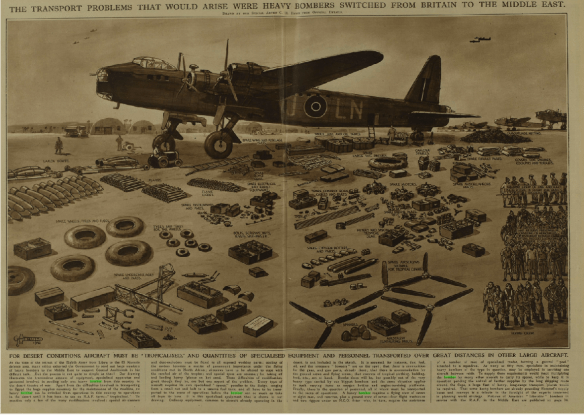

The deployment of air forces also imposed logistical problems, as this graphic from the Illustrated London News showed:

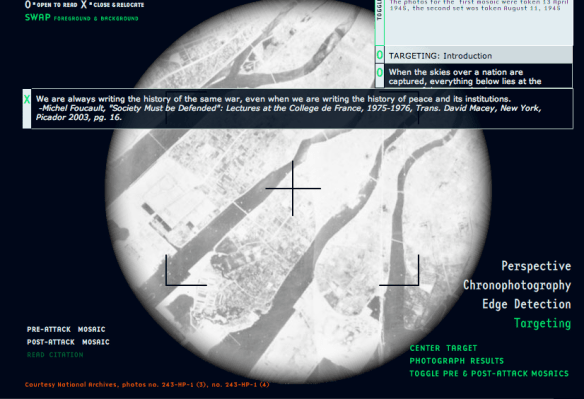

It’s worth remembering that today’s use of UAVs like the Predator and Reaper in distant theatres of war and conflict zones also requires the transport of the aircraft, ground crews and the crews responsible for take-off and landing; once airborne, the missions are usually flown from the continental United States but they involve an extended global network of supplies, personnel and communications.

In fact, writing in 2004 Creveld concluded that since 1945 the logistics burden had not eased nor had armed forces increased their operational freedom. The two most important changes have been an even greater reliance on petrol/gasoline (a key target of Allied bombing in the final stages of the Second World War) which, by the 1990s, had displaced ammunition to become the single bulkiest commodity to be shipped to supply distant wars, and a dramatic increase in outsourcing through the use of private military contractors.

I provided a sketch of how these two developments bear on the contemporary logistics of supplying war in Afghanistan in a long essay at open Democracy, and I’ve provided a short update here. This was my conclusion:

‘Over the last decade a new political economy of war has come into view. We have become aware of late modern war’s proximity to neoliberalism through privatisation and outsourcing (‘just-in-time war’) and its part in the contemporary violence of accumulation by dispossession. The rapacious beneficiaries of the business of war have been swollen by the transformation of the military-industrial complex into what James der Derian calls the military-industrial-media-entertainment network (MIME-NET). And the very logic of global financial markets has been subsumed in what Randy Martin calls today’s ‘derivative wars’. These are all vital insights, but it is important not to overlook the persistence of another, older and countervailing political economy that centres on the persistence of the friction of distance even in the liquid world of late modernity. To repeat: the world is not flat – even for the US military. In a revealing essay on contemporary logistics Deborah Cowen has shown how the United States has gradually extended its ‘zone of security’ outwards, not least through placing border agents around the world in places like Port Qasim [in Pakistan] so that the US border becomes the last not the first line of defence through which inbound flows of commodities must pass. She shows, too, how the securitization security of the supply chain has involved new legal exactions and new modes of militarization that materially affect port access, labour markets and trucking systems. Affirming the developing intimacy, truly the liaison dangereuse between military and commercial logistics, the US Defense Logistics Agency envisages a similar supply chain for its outbound flows that aim to provide ‘uninterrupted support to the warfighter’ (‘full spectrum global support’) and a ‘seamless flow of materiel to all authorized users.’ And yet, as I hope I have demonstrated, this is the ‘paper war’ that, 180 years ago, Clausewitz contrasted so scathingly with ‘real war’. The friction of distance constantly confounds the extended supply chain for the war in Afghanistan. This is no simple metric (‘the coefficient of distance’) or physical effect (though the difficult terrain undoubtedly plays a part). Rather, the business of supplying war produces volatile and violent spaces in which – and through which – the geopolitical and the geo-economic are still locked in a deadly embrace.’

And, as that last phrase signals, I’ll need to deepen and extend all these arguments for the book-length version of Deadly embrace. We are still a long way from the Montreal Gazette’s nineteenth-century dream of ‘frictionless war’.