Further to my post about Remote Witnessing, Robert Beckhusen at Danger Room reports that Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir is calling for the African Union to ‘protect’ African space from spy satellites. Beckhusen suggests that al-Bashir has DigitalGlobe and, more particularly, the Satellite Sentinel Project squarely in his sights.

Using DigitalGlobe’s remote imagery, SSP’s website explains that

the Satellite Sentinel Project can identify chilling warning signs — elevated roads for moving heavy armor, lengthened airstrips for landing attack aircraft, build-ups of troops, tanks, and artillery preparing for invasion — and sound the alarm.

In other cases, SSP has notified the world of heinous crimes that would go otherwise undocumented and unreported. DigitalGlobe imagery supports evidence of alleged mass graves, razed villages, and forced displacement. SSP shines a spotlight on the atrocities committed in Sudan and lets alleged perpetrators know that the world is watching.

SSP‘s reports containing high resolution imagery are available to everyone, from journalists to the International Criminal Court. SSP‘s reports have been used as evidence in the International Crimal Court investigation of recent alleged crimes in Sudan.

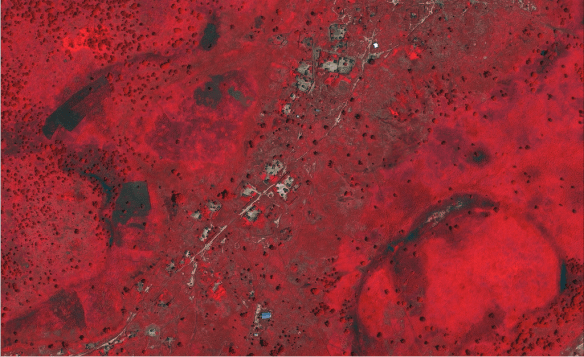

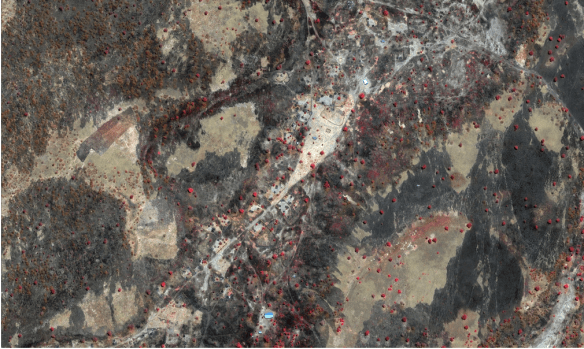

One example might indicate the scope of the project. In a report dated 20 July 2012 SSP provided compelling evidence of the deliberate razing of the village of Um Bartumbu in Sudan’s border region. SSP compared DigitalGlobe imagery from September 2011 and March 2012 (all captions from SSP):

A DigitalGlobe satellite image, taken on September 11, 2011, shows the Sudanese village of Um Bartumbu prior to the village being destroyed by fire. The vegetation around the village (which appears red in the near-infrared imagery) appears healthy and unharmed. The village itself does not appear to be damaged in any way.

A DigitalGlobe satellite image shows the Sudanese village of Um Bartumbu, after it has been apparently destroyed by fires. A large portion of the vegetation within the village and the surrounding area has sustained extensive fire damage. Evidence of burning extends more than 6 miles (10 km) to the west and south of the village. Although it is clear that the great majority of the village suffered fire damage, satellite imagery alone cannot confirm the destruction of the clinic, mosque, storerooms, grinding mill or church because their metal roofs appear intact.

SSP claimed that its findings corroborate eyewitness reports that a joint unit of Sudan Armed Forces and Popular Defense Force militia razed the village in late 2011:

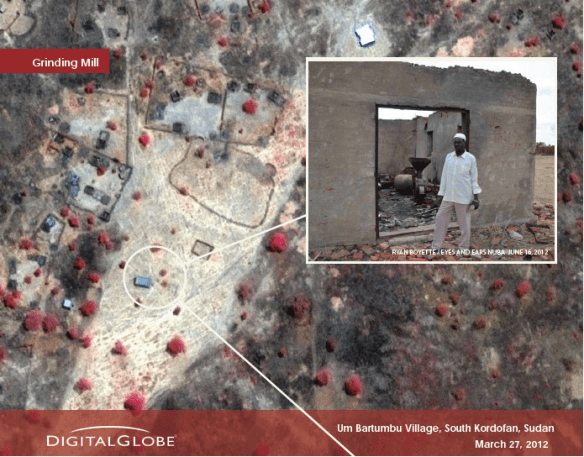

SSP has obtained new videos and photographs taken by Eyes and Ears Nuba, a team of citizen journalists based in rebel-held territory in the Nuba Mountains. The team traveled to Um Bartumbu with GPS-equipped cameras on June 16, to document evidence of the razing of this village, which sits in a no-man’s-land between opposing forces in Sudan’s ongoing conflict. An Um Bartumbu elder reported that the now-abandoned village had contained 50 homesteads of Muslims and Christians, numbering approximately 250 adults, plus an unspecified number of children.

An undated cell phone video obtained by SSP from Eyes and Ears Nuba, and available on NubaReports.org, shows Sudanese forces who call themselves “Katiba Kabreet,” Sudanese Arabic for “Match Battalion,” setting fire to a village. In the video, Sudanese men fire guns and carry torches as residential compounds burn. Most wear matching uniforms and boots, and are dressed in a manner consistent with Sudan Armed Forces. Some wear mismatched uniforms and tennis shoes, and are dressed in a manner consistent with PDF militia forces.

“Matches, where are the matches? Burn this house,” one soldier commands in Sudanese Arabic.

SSP’s case is made so compelling through its forensic triangulation of the site through satellite imagery, ground imagery and eye-witness reports; for the full suite of satellite and ground imagery, see the collection here.

The communal grinding mill in Um Bartumbu, 27 March 2012 (near infrared), 16 June (inset) and 22 January (close up).

SSP links to Eyes and Ears Nuba, which describes itself as ‘a network of citizen reporters dedicated to covering the war along the Nuba Mountains’ where, after fighting broke out in June 2011, the government of Sudan banned journalists from entry. ‘The only witnesses are Nubans’, and for this reason ‘Nuba Reports was founded in order to provide the international community and the people of Sudan with credible and compelling dispatches from the frontlines.’

Witnessing, then, becomes a multi-modal, highly mediated structure of testimony, inference and evidence: always situated, inescapably precarious, and absolutely vital. And, as I noted in that previous post, it cannot be conducted from remote desk-tops alone.

Note: The Small Arms Survey has a helpful backgrounder on the region here, and for more on the genocide unfolding in the Nuba Mountains see here and here and here. Nicholas Kristof has also provided a series of anguished reports for the New York Times – for example here– and Brett McDonald’s video of Kristof’s travels is available here.

![Saucepans into Spitfires [Imperial War Museum]](https://geographicalimaginations.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/large.jpg?w=584)