Following my post on artists and bombing, and in particular the work of elin o’Hara slavick, elin has written with news of her new book, After Hiroshima, due in March from Daylight, with what she calls a ‘ridiculously brilliant essay’ from James Elkins.

Following my post on artists and bombing, and in particular the work of elin o’Hara slavick, elin has written with news of her new book, After Hiroshima, due in March from Daylight, with what she calls a ‘ridiculously brilliant essay’ from James Elkins.

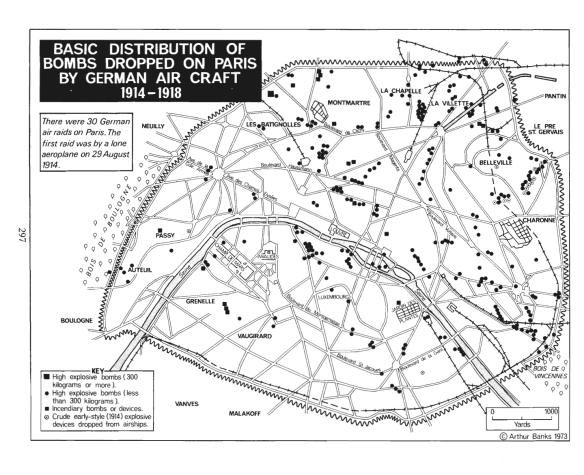

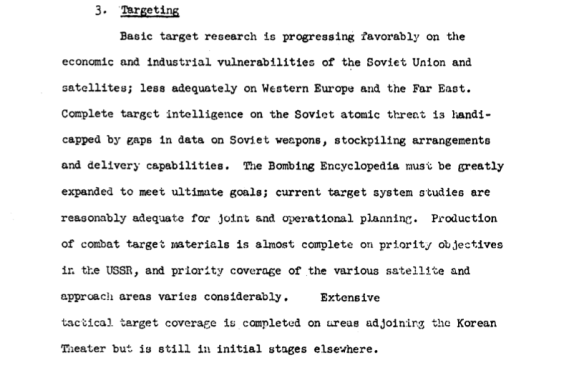

If you’re interested in two different but none the less intimately related works, I recommend Paul Ham‘s Hiroshima Nagasaki (Doubleday, 2012), which is extraordinarily good at placing those terrible attacks in the context of a strategic air war waged primarily against civilians (according to the Air Force Weekly Intelligence Review at the time, ‘There are no civilians in Japan’: sound familiar?) – and this needs to be read in conjunction with David Fedman and Cary Karacas, ‘A cartographic fade to black: mapping the destruction of urban Japan in World War II’, Journal of historical geography 38 (2012) 303-26 (you can get a quick visual version here) – and Rosalyn Deutsche’s Hiroshima after Iraq: three studies in art and war (Columbia, 2010), based on her Wellek Library Lectures in Critical Theory given in 2009.

You can get a preview of elin’s ‘After Hiroshima’ project here. Scrolling down that page, my eye was caught by the image ‘Woman with burns through kimono’, taken in 1945, which transported me to another ridiculously brilliant work, Kamila Shamsie‘s dazzling novel Burnt Shadows. I’ve been haunted by it ever since I read it, and in the draft of the first chapter of The everywhere war I start with this passage from the novel:

And this is how I go on (and please remember this is a draft):

A man is being prepared for transfer to the American war prison at Guantanamo Bay: unshackled, he strips naked and waits on a cold steel bench for an orange jumpsuit. ‘How did it come to this?’ he wonders. This is the stark prologue to Kamila Shamsie’s luminous novel Burnt Shadows. She finds her answer to his question in a journey from Nagasaki in August 1945 as the second atomic bomb explodes, through Delhi in 1947 on the brink of partition, to Pakistan in 1982-3 as trucks stacked with arms grind their way from the coast to the border training-camps, and so finally to New York, Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay in 2001-2. These are all, in their different ways, conflict zones and the turning-points of empires, tracing an arc from the cataclysmic end of the Second World War through the Cold War to the wars fought in the shadows of 9/11. In this book, I follow in her wake; I find myself returning to her writing again and again. Although this is in part the product of her lyrical sensibility and imaginative range, there are three other reasons that go to the heart of my own project and which provide the framework for this chapter.

The first flows from the historical arc of the novel. Shamsie is adamant that Burnt Shadows is not her ‘9/11 novel’. She explains that it is not about the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001 but about the cost and consequences of state actions before and after. Her long view reveals that the connections between Ground Zero in 1945 and Ground Zero in 2001 are more than metaphorical. These are connections not equivalences – and far from simple – but like Shamsie I believe that many of the political and military responses to 9/11 can be traced back to the Cold War and its faltering end and, crucially, that the de-stabilization of the distinction between war and peace was not the febrile innovation of the ‘war on terror’. I start by mapping that space of indistinction, and it will soon become clear that the dismal architects of the ‘war on terror’ (the scare-quotes are unavoidable) not only permanently deferred any prospect of peace but claimed to be fighting a radically new kind of war that required new allegiances, new modalities and new laws. Here too there are continuities with previous claims about new wars fought by the advanced militaries of the global North, conducted under the sign of a rolling Revolution in Military Affairs and its successor projects, and quite other ‘new wars’ fought by rag-tag militias in the global South: all of them preceding 9/11.

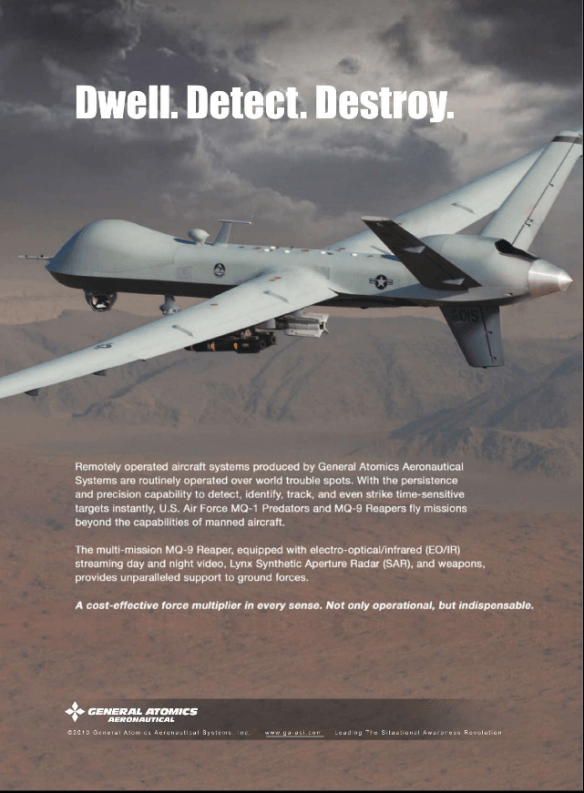

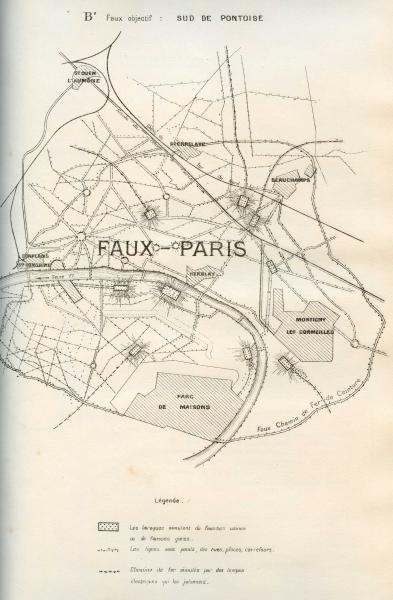

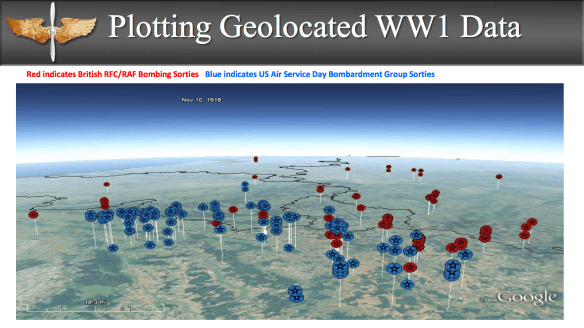

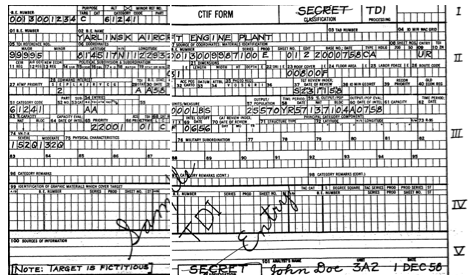

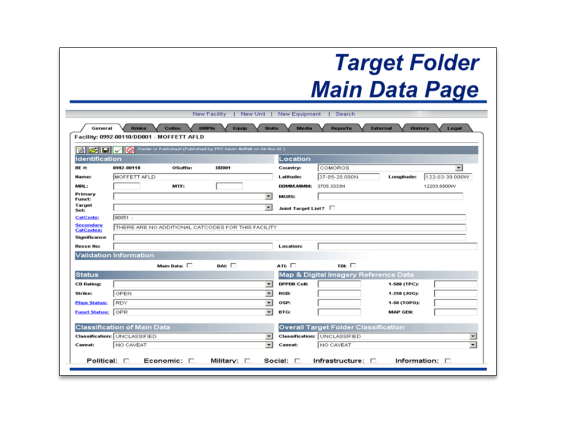

I turn to those new wars next, and this brings me to the second reason why Shamsie’s work is relevant to my own discussion. While she was writing Burnt Shadows she used Google Earth to disclose the textures of New York City, and marvelled at how obediently they swam into view: ‘3D models of buildings, amazingly high-resolution images, links to photographs and video streams of Manhattan.’ When she turned to Afghanistan, however, all the details dissolved into ‘an indistinct blur, and the only clues to topography came from colours within the blur: blue for rivers, brown for desert, green for fertile land.’ But that was then (2006). Three years later, a different Afghanistan was brought into view. ‘As I click through all the YouTube links tattooed across the skin of Afghanistan,’ she wrote, ‘I encounter video clips of American solders firing on the Taliban, Canadian politicians visiting troops, Dutch forces engaged in battle, an IED blast narrowly missing a convoy of US soldiers, a video game in which a chopper hails down missiles and bullets on a virtual city which looks more like Baghdad than Kabul.’ Shamsie uses these distinctions to remind us that ‘we’re still using maps to inscribe our stories on the world.’ So we are; and throughout this book I also turn to these violent cartographies, as Michael Shapiro calls them: maps, satellite images and other forms of visual imagery. These inscriptions and the narratives that they impose have a material form, and they shape both the ways in which we conduct ‘our’ wars and also the rhetoric through which we assert moral superiority over ‘their’ wars. Yet even as I sketch out these contrasting imaginative geographies, another indistinction – a blurring, if you like – seeps in. For one of the most telling features of contemporary warscapes is the commingling of these rival ‘new wars’ in the global borderlands, the ‘somewhere else’ that Abdullah reminds Kim is always the staging ground of America’s wars.

And this brings me to the final reason for travelling with Burnt Shadows: Abdullah’s insistence that war is like a disease. This is an ironic reversal of the usual liberal prescription that justifies war – which is to say ‘our’ war – as a necessity: ‘killing to make life live’, as Michael Dillon and Julian Reid put it. They argue that war in the name of liberalism is a profoundly bio-political strategy in which particular kinds of lives can only be secured and saved by sacrificing those of others. You might say that war has always been thus, but what is distinctive about the contemporary conjunction of neo-liberalism and late modern war is its normative generalization of particular populations as at once the bearers and the guardians of the productive potential of ‘species-life’. Here too there are terrible echoes of previous wars, and these brutal privileges depend, as they often did in the past, on discourses of science and economics (and on the couplings between them). But contemporary bio-politics also draws its succour from new forms of the life sciences that treat life as ‘continuously emergent being’. This is to conjure a world of continuous transformation in which emergence constantly threatens to become emergency: in which there is the ever-present possibility of life becoming dangerous to itself. For this reason the social body must be constantly scanned and its pathologies tracked: security must deal not with a grid of fixed objects but a force-field of events, and war made not a periodic but a permanent process of anticipation and vigilance, containment and elimination. Mark Duffield calls this ‘the biopolitics of unending war’ – war that extends far beyond the killing fields –in which the global borderlands become sites of special concern. Its prosecution involves the production of new geographies – new modes of division and distinction, tracing and tracking, measuring and marking – that provide new ways of continuing the liberal project of universalizing war in the pursuit of ‘peace’. In the face of all this, Abdullah had a point.