In an astonishing essay on ‘Drone bombings in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas’, published in the Journal of Geographical Information Systems 4 (2012) 136-141 – the places this blog is taking me! – Katrina Laygo, Thomas Gillespie, Noel Rayo and Erin Garcia (three geographers and a political scientist at UCLA) explore what they call ‘public remote sensing applications for security monitoring’.

An open-access version should be available here but there is also a manuscript version here. (In fact news of the project appeared in the press soon after the US raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound last year – Gillespie and John Agnew headed a team that had used satellite imagery and the theory of island biogeography (sic) to predict the location of bin Laden’s hideout in 2009 – but much of the media interest in the new work focused on the image captured by satellite of a Predator circling above an area south west of Miram Shah.)

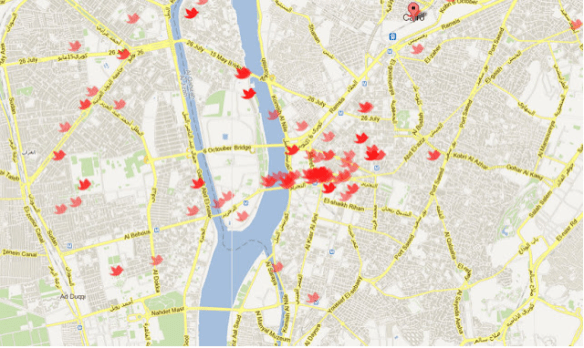

The new project uses unclassified high-resolution imagery from QuickBird 2 (via GeoEye) to monitor drone strikes in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). The difficulties (and dangers) of eyewitness reports are well-known, and media coverage of drone strikes in the area is at best uneven – though the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, along with organizations like CIVIC and Reprieve, continue to do brave, invaluable, eye-popping work – but the UCLA team concludes that, in principle, the commercial availability of the satellite imagery means that ‘it is possible for the public’ – a distant public – ‘to monitor drone bombings in the [FATA]’.

You can see where they might be going. In the weeks preceding the US-led invasion of Afghanistan the Pentagon secured exclusive rights to commercial imagery from the Ikonos-2 satellite. They didn’t need it for operational purposes; the objective was to exercise ‘shutter control’ and prevent media and other organizations from obtaining imagery that might reveal casualties from the high-level bombing campaign. It wasn’t cheap; the standard cost was around $200 per square kilometre, with a premium for rapid turnaround, and news media had been paying $500 for each image. It’s still not cheap. The authors of this (I presume preliminary) report concede that ‘it may be prohibitively expensive to monitor the entire region’. They estimate that weekly data for one year’s coverage of a town like Miram Shah would cost $64,000, though this would not be beyond the reach of some organizations.

But their own test-case is not encouraging. Working from a map of drone strikes and casualties constructed by the Center for American Progress – they don’t say why they selected this source – the team searched the satellite image for evidence of any of the 16 drone strikes around Miram Shah before 1 January 2010 included in the database. This is what they say:

‘We feel confident that we were able to identify the location of one drone bombing in Figure 4(b). If the center of the compound is the target, it would appear that the drone bombing is accurate. This also suggests that the blast radius of such attacks is relatively small or less than 20 m. Indeed, the walls still appear to remain intact. This appears similar to blast radii reported for hellfire missiles which are used by both the Predator and Reaper drones.’

The claim is not only repeated but generalized in the abstract: ‘Results suggest that drone bombings are very accurate and drone missions are common in the region.’

They suggest no such thing; drone strikes are most certainly common, but the claim about their accuracy is based on a single case for which nothing is known of the intended target or the basis for its identification – was this yet another wedding party? Neither can anything be said about civilian casualties; they don’t key this site back into their casualty database, such as it is, and in any case they note that ‘The resolution of QuickBird 2 is currently not high enough to see or quantify casualties.’ Not exactly forensic architecture then.

Not surprisingly, though, the conclusion chimes with the Center for American Progress’s own endorsement of the campaign:

Hardly a week goes by without some key figure in the Al Qaeda network and its affiliates being targeted in a range of actions, including drone strikes as well as other actions by U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies to prevent attacks and degrade the Al Qaeda network. The damage done to Al Qaeda by the Obama administration represents America’s greatest national security success since the fall of the Soviet Union and the peaceful integration of Eastern European countries in the 1990s.

The importance of all this goes beyond the particular case. Susan Sontag once famously declared that ‘Being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country is a quintessentially modern experience.’ It’s a more complicated (and contentious) claim than it looks, but in any event being a spectator is not the same as being a witness. And we surely know – or ought to know – from Lisa Parks‘s wonderful work that satellite and other remote technologies do not provide an unmediated window on the world. I’m thinking particularly of her ‘Satellite view of Srebrenica: tele-visuality and the politics of witnessing’ in Social identities 7 (4) (2001), and ‘Digging into Google Earth: an analysis of “Crisis in Darfur”‘ in Geoforum 40 (4) (2009), but you can get a sense of her work from the press report of her 2010 lecture to the New Zealand Geographical Society here. She also has a new book out late this year/early next from Routledge, Coverage: media spaces and security after 9/11.

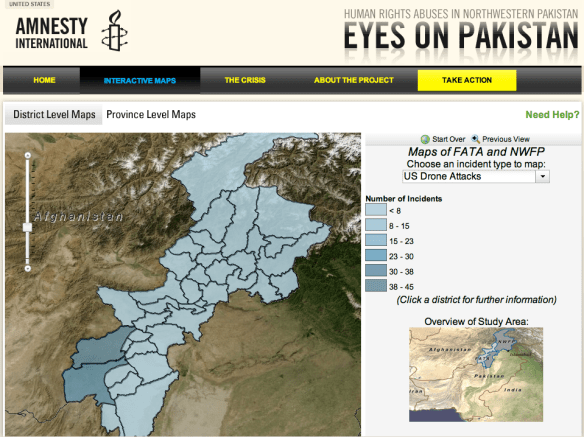

Now the use of satellite technology to conduct ‘remote witnessing’ is not alien to human rights organizations, but most of them are well aware of its problems as well as its potential. Amnesty International sponsored the Science for Human Rights Project (originally Satellites for Human Rights) from January 2008 to January 2011:

Its primary purpose was to test the potential use of geospatial technologies for human rights impact. The purpose of the evaluation is to assess the extent to which work undertaken by Amnesty International contributed to change (intended and unintended) and to assess the potential for using geospatial technologies to contribute towards more effective advocacy and impact.

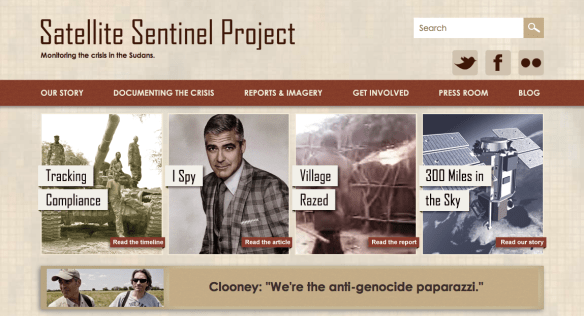

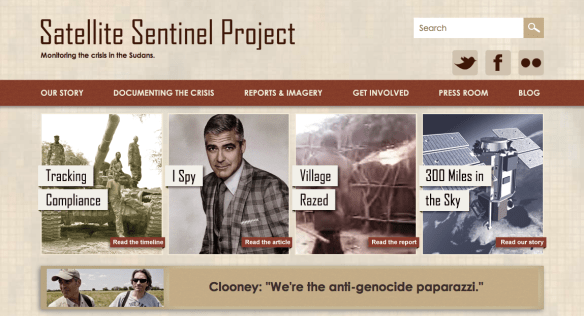

There have been a series of public examples. Some of them have been conducted under other banners, like the celebrity Satellite Sentinel Project on Sudan.

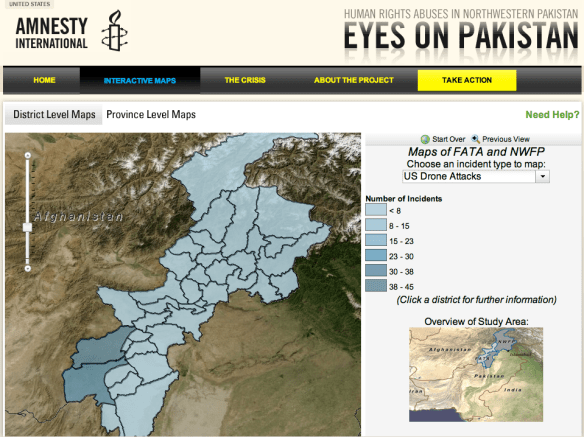

But the most directly relevant to this post is probably Amnesty’s (now terminated) Eyes on Pakistan archived here. Although this involved interactive mapping platforms rather than the use of satellite imagery the project title gives a clear indication of the direction in which Amnesty was moving and the wider debate about witnessing of which it was a part.

Amnesty has also launched Eyes on Darfur (here too the imagery is no longer being updated) and now Eyes on Syria. This does involve remote imagery, and there is an interesting discussion on Amnesty USA’s blog about its significance:

The images from Homs and Hama show clearly that armed forces have not been removed from residential areas, as demanded by the U.N. General Assembly resolution from mid February. In Hama, the images reveal an increase in military equipment over the last weeks, raising the specter of an impending assault on the city where the father of current President Bashar al-Assad unleashed a bloody 27-day assault three decades ago, with as many as 25,000 people killed.

With reports of a ground assault underway in Homs, the analysis of imagery identifies military equipment and checkpoints throughout Homs, and field guns and mortars actively deployed and pointing at Homs [see image left]. Additionally, the images show the shelling of residential areas in Homs, concentrated on the Bab ‘Amr neighborhood. Artillery impact craters are visible in large sections of Bab ‘Amr, from where we have received the names of hundreds killed throughout the period of intense shelling.

With reports of a ground assault underway in Homs, the analysis of imagery identifies military equipment and checkpoints throughout Homs, and field guns and mortars actively deployed and pointing at Homs [see image left]. Additionally, the images show the shelling of residential areas in Homs, concentrated on the Bab ‘Amr neighborhood. Artillery impact craters are visible in large sections of Bab ‘Amr, from where we have received the names of hundreds killed throughout the period of intense shelling.

Note that last clause: to convert remote sensing into remote witnessing requires difficult, painstaking work in multiple registers because the imagery does not speak for itself. To believe otherwise means that anyone who ventriloquises from imagery alone – academics screening imagery in California or CIA/USAF analysts scrutinising near real-time feeds from drones – runs the real risk of seeing what they are predisposed to see. As that same blog post notes,

Satellite images can help to show the widespread and systematic nature of violations, characteristics inherent to certain international crimes such as crimes against humanity. Additionally, they can help in identifying command responsibility, a key requirement for holding individual perpetrators accountable. [Ivan] Simonovic [Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights] pointed out that the UN Panel on Sri Lanka relied a lot on satellite images. The same holds true for the current commission of inquiry on Syria, which equally relies on satellite images. Thus, the point is that while satellite images barely deliver the “smoking gun” that leads to a conviction, they can provide major support for international investigations and accountability mechanisms.

And this brings me back to drones. Writing in the New York Times on 30 January 2012 Andrew Sniderman and Mark Hanis proposed re-purposing drones ‘for human rights’:

DRONES are not just for firing missiles in Pakistan. In Iraq, the State Department is using them to watch for threats to Americans. It’s time we used the revolution in military affairs to serve human rights advocacy. With drones, we could take clear pictures and videos of human rights abuses, and we could start with Syria. The need there is even more urgent now, because the Arab League’s observers suspended operations last week. They fled the very violence they were trying to monitor. Drones could replace them, and could even go to some places the observers, who were escorted and restricted by the government, could not see. This we know: the Syrian government isn’t just fighting rebels, as it claims; it is shooting unarmed protesters, and has been doing so for months. Despite a ban on news media, much of the violence is being caught on camera by ubiquitous cellphones. The footage is shaky and the images grainy, but still they make us YouTube witnesses. Imagine if we could watch in high definition with a bird’s-eye view. A drone would let us count demonstrators, gun barrels and pools of blood. And the evidence could be broadcast for a global audience, including diplomats at the United Nations and prosecutors at the International Criminal Court.

This produced a series of responses: Lauren Jenkins was appalled, Daniel Solomon sceptical, and Patrick Meier sympathetic. The most scathing response was from anthropologist Darryl Li in Middle East Report, which provoked a heated exchange between him and Sniderman. I see all this as part of a diffuse (and I think largely uncoordinated) campaign to rehabilitate drones in the public eye, something I’ll be writing about in a future column for open Democracy. But whatever you make of it, and wherever your sympathies lie, the debate about ‘humanitarian drones’ clearly underscores the necessity of seeing visual technologies as political-cultural technologies enrolled in highly particular scopic regimes.

In short – and to return to where I started – remote witnessing is not a passive practice but an intervention in a field of power and as such it involves a series of investments that spiral far beyond the cost of obtaining the imagery.

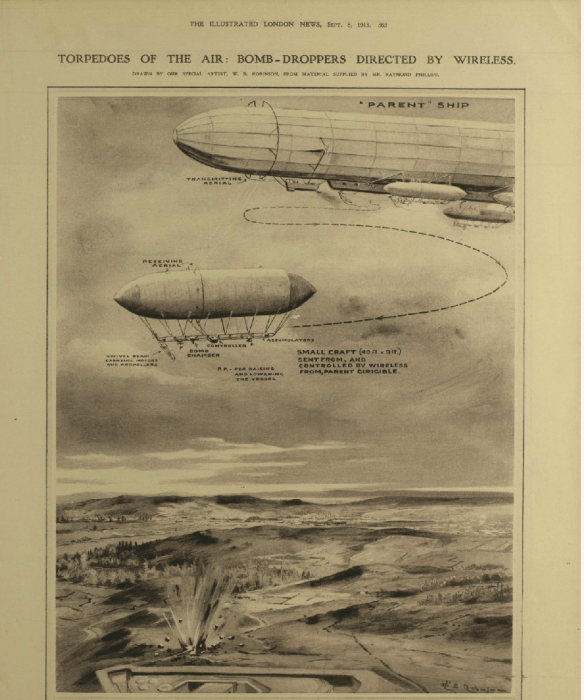

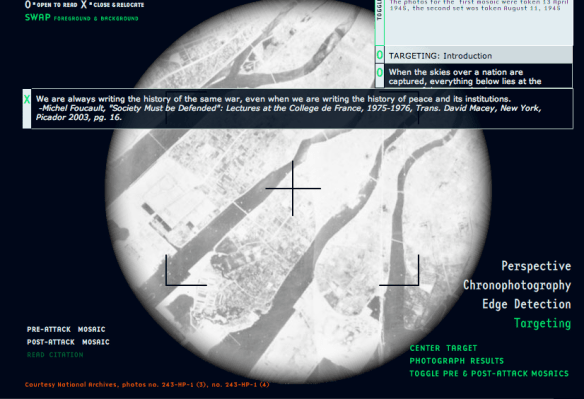

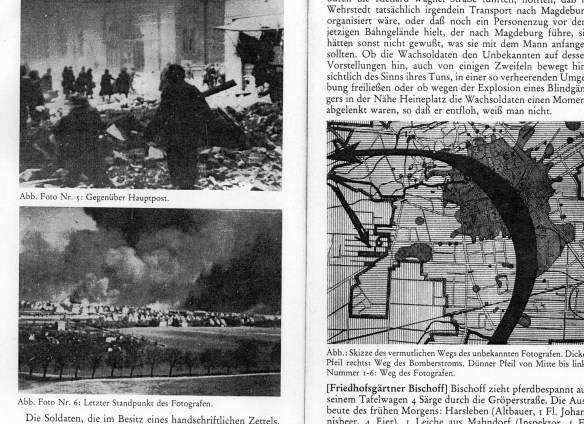

What is particularly interesting to me are the ways in which ‘seeing like a drone’ is and is not like seeing through a standard bombsight: the techno-optical regime through which conventional bombing has been conducted differs from the high-resolution full-motion video feeds that inform (and misinform) the networked bombing of late modern war. Those feeds significantly compress the imaginative distance between the air and the ground, but they do so in a highly selective fashion. Today’s remote operators, who may be physically thousands of miles away from the target, nevertheless claim to be just 18 inches from the conflict zone, the distance between the eye and the screen, and they (un)certainly see far more of what happens than the pilots of conventional strike aircraft. But in Afghanistan, where remote operators are usually working with troops on the ground, they become immersed in the actions and interactions of their comrades – through visual feeds, radio and internet – whereas their capacity to interpret the actions of the local population is still strikingly limited. So it is that local lifeworlds remain not only obdurately ‘other’ but become death-worlds.

What is particularly interesting to me are the ways in which ‘seeing like a drone’ is and is not like seeing through a standard bombsight: the techno-optical regime through which conventional bombing has been conducted differs from the high-resolution full-motion video feeds that inform (and misinform) the networked bombing of late modern war. Those feeds significantly compress the imaginative distance between the air and the ground, but they do so in a highly selective fashion. Today’s remote operators, who may be physically thousands of miles away from the target, nevertheless claim to be just 18 inches from the conflict zone, the distance between the eye and the screen, and they (un)certainly see far more of what happens than the pilots of conventional strike aircraft. But in Afghanistan, where remote operators are usually working with troops on the ground, they become immersed in the actions and interactions of their comrades – through visual feeds, radio and internet – whereas their capacity to interpret the actions of the local population is still strikingly limited. So it is that local lifeworlds remain not only obdurately ‘other’ but become death-worlds.