To mark the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, there has been widespread interest in a haunting video shot for the BBC using a commercial drone:

For once, the emptiness of the scene – just buildings, fences and railway tracks – is desperately affecting. It’s surely impossible to watch this without thinking of the millions of people whose lives were so brutally effaced by the murderous regime of the Third Reich. The only sign of a human presence in the video is a glimpse over the wall of trucks racing by: a reminder that Auschwitz was (and disconcertingly remains) at the centre of a small town (see also my post on Auschwitz here).

There are at least two other films that ought to be seen too.

The first is a documentary commissioned in 1945 by the Psychological Warfare Film Section of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force to document the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. The producer was Sidney Bernstein, for Britain’s Ministry of Information; Alfred Hitchcock was drafted in as a ‘treatment adviser’. The working title was German Concentration Camps: Factual Survey; it was never shown in its entirety (though Billy Wilder turned the footage into a short, Death Mills), and the Imperial War Museum notes:

From the start of the project, there were a number of problems including the practical difficulties of international co-operation and the realities of post-war shortages. These issues delayed the film long enough to be overtaken by other events including the completion of two other presentations of concentration camp footage to the German people and the evolution of occupation policy, where the authorities no longer considered a one-hour compilation of atrocity material appropriate. The last official action on the film was a screening of an incomplete rough-cut on 29 September 1945, after which the film was shelved, unfinished.

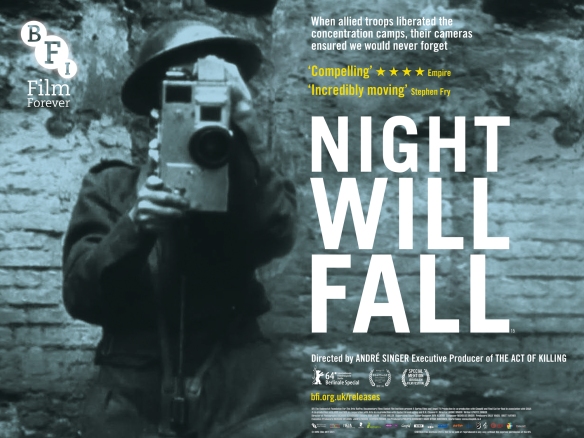

The footage has now been incorporated into a stunning HBO documentary, Night Will Fall, directed by André Singer, who was an Executive Producer for Act of Killing (see my posts here, here and here).

There are all sorts of stories about why the full version was never shown – see the Guardian‘s report here – but the fullest discussions are Kay Gladstone‘s ‘Separate intentions’ in Toby Haggith and Joanna Newman (eds) Holocaust and the moving image (2005) (see also Haggith’s ‘Filming the liberation of Bergen-Belsen here) and her ‘Memory of the Camps: the rescue of an abandoned film’, in Griselda Pollock and Max Silverman (eds) Concentrationary cinema (2011).

The second film returns to the aerial view and to Auschwitz: Harun Farocki’s Images of the world and the Inscription of War. Shockingly and sadly, Farocki died last summer at the age of 70, and Images is widely regarded as his masterpiece (see Thomas Voltzenlogel‘s wide-ranging and appreciative discussion of ‘Dialectics in images’ here). The central motif is an image taken from a series of aerial photographs of Auschwitz shot by the Allies between April 1944 and January 1945 (see also here and here).

This image was taken on 4 April 1944 by Lt Charles Barry flying a Mosquito from 60 Photo Reconnaissance Squadron of the South African Air Force. From the film’s commentary [available in Discourse 5(3) (1993) 78-92]:

American aircraft had taken off in Foggia, Italy, and flown towards targets in Silesia – factories for synthetic petrol and rubber – known as Buna.

On the flightover the IG Farben company factory still under construction, a pilot clicked his camera shutter and took photographs of the Auschwitz concentration camp.

First picture of Auschwitz taken at 7,000 meters altitude.

The pictures taken in April 1944 in Silesia arrived for evaluation in Medmenham, England [the RAF’s Central Intelligence Unit concerned with air photograph interpretation].

The analysts discovered a power station, a carbide factory, a factory under construction for Buna and another for petrol hydrogenation.

They were not under orders to look for the Auschwitz camp, and thus they did not find it.

How close the one is to the other: the industry – the camp.

It was not until 1977 that two employees of the CIA [Dino Brugioni and Robert Poirer: see their detailed report here] went through the archives to find and evaluate the photographs of Auschwitz. It was not until thirty-three years later that the following words were inscribed:

Tower and Commandant’s house and

Registration Building and Headquarters and Administration and

Fence and execution wall and Block 11 and the word “Gas chamber” was inscribed.

Kaja Silverman adds this gloss [‘What is a camera?’ Discourse 5 (30 (1993) 3-56]:

Not only does the camera here manifestly “apprehend” what the human eye cannot, but the latter seems strikingly handicapped by its historical and institutional placement, as if to suggest that military control attempts to extend beyond behavior, speech, dress,and bodily posture to the very sensory organs themselves. This sequence indicates, in other words,that military discipline and the logic of warfare function to hyperbolize the distance separating look from gaze and to subordinate the former completely to the latter.

These are similar issues that haunt my own discussions of the video feeds from Predators and Reapers over Afghanistan and Iraq. In another commentary, Christa Blümingler writes:

The vanishing point of Images of The World is the conceptual image of the ‘blind spot’ of the evaluators of aerial footage of the IG Farben industrial plant taken by the Americans in 1944. Commentaries and notes on the photographs show that it was only decades later that the CIA noticed what the Allies hadn’t wanted to see [my emphasis]: that the Auschwitz concentration camp is depicted next to the industrial bombing target.

The claim that the ‘Allies didn’t want to see’ spirals through an important debate about whether the Allies could or should have bombed Auschwitz (see, in addition to the symposium on the right, here and here). In fact, as Christa observes later,

The claim that the ‘Allies didn’t want to see’ spirals through an important debate about whether the Allies could or should have bombed Auschwitz (see, in addition to the symposium on the right, here and here). In fact, as Christa observes later,

In … 1944, the allies bombed not Auschwitz, but the IG Farben factory nearby the death camp. Drawing on analyses of these events, how and why the allies didn’t act on their knowledge of the mass destruction of the Jews, Farocki … decodes a host of military images, focusing on two visual dispositives: American pilots in 1944 and CIA agents in 1977 offering two different [readings] of the aerial photographs of Auschwitz.

In this instance, Farocki developed an epistemological field of technological history — measurement and surveillance in a period of rapid automatization. At the end of the film, a blind spot in the photographic act, referring back to the reality of the concentration camp, becomes visible.

The final shots further emphasize details of the American pilots’ aerial photos, which are picked up in the sweep of the film several times, framed and arranged in different ways. At the end of the film, through a permutative movement of cuts, the extreme enlargement of the photographs reminds us once again of their materiality. Farocki shows these images in precisely the spaces where visual thought takes place, and in connection to specific techniques of reproduction and distribution (in albums, archives, institutions). Whenever he used marginal and hard-to-access image materials from specialized archives, he sought to consider these conditions of visibility in his analysis.

What particularly interests me, and the reason I juxtapose these two films, is an interview with Chris Darke in 2003 in which Farocki artfully tracks between the eye-witness and the aerial shot:

Chris Darke: In Images of the World and the Inscription of War there is this repeated phrase: “Beside the real world there is a second world, a world of pure military fiction”. I was very strongly reminded of Colin Powell at the UN Security Council presenting degraded military surveillance images as proof and justification for military action.

HF: Yes, it reminded me so much of the Auschwitz sequences in Images of the World, the way they involved aerial reconnaissance images that you had to be a specialist to read. Who knows what they are telling you? Who knows what happened there? What is so interesting is that the personal witness of two people who had escaped from the camps was so important. It was the way that traditional history was always written. You need an eye-witness, a narrative, otherwise you’ll never believe in it. And it turns out that our imaginative minds are still very old-fashioned. We don’t understand modernist strategies such as those used by the Americans in the first Gulf War. You really want to see these terrible, dirty images of burning streets and wounded people in the same way that psychoanalysis knows that you need dirty thoughts for the imagination, just as for love you need dirty images. The audience is not prepared for this automatically recorded history that more or less happens already, where everything is recorded; so there has to be an old-fashioned drama made out of it.

There are at least two other detailed commentaries on the film that address the question of visuality in depth: Thomas Keenan‘s ‘Light weapons’, in Documents 1/2 (1992) 147-58 and Nora Alter‘s ‘The political im/perceptible in the essay film: Farocki’s Images of the world and the inscription of war‘, in New German Critique 68 (1996). More generally, I also recommend the special issue of e-flux on Farocki’s work here, including a commentary by Trevor Paglen on Farocki’s ‘operative images’, and David Cox‘s brief commentary here.

Note: Belinda Gomez writes (in relation to the commentary for Images of the World):

“Fence and execution wall and Block 11 and the word “Gas chamber” was inscribed….” But that’s not quite accurate. Brugioni and Poirier didn’t write that in 1977. The gas chamber didn’t have a sign. That they were able to locate the gas chamber and crematoria was due to their superior technology and they knew what they were looking for. The pilot/photographers in 1944 took photos of the factory and what was taken as a workers camp. To say that they didn’t see Auschwitz because they weren’t told to look for it is more of a hind-sight interpretation.