The New Aesthetic began to create its public at the Really Interesting Group in May 2011 with this post from James Bridle:

For a while now, I’ve been collecting images and things that seem to approach a new aesthetic of the future, which sounds more portentous than I mean. What I mean is that we’ve got frustrated with the NASA extropianism space-future, the failure of jetpacks, and we need to see the technologies we actually have with a new wonder. Consider this a mood-board for unknown products.

(Some of these things might have appeared here, or nearby, before. They are not necessarily new new, but I want to put them together.)

For so long we’ve stared up at space in wonder, but with cheap satellite imagery and cameras on kites and RC helicopters, we’re looking at the ground with new eyes, to see structures and infrastructures…

The post digitally curated a series of images – a sort of wunder-camera (hah!) – and soon afterwards James’s first post appeared on tumblr as The New Aesthetic. The site grew and grew, though not quite like Topsy, and this is is how he now explains his experimental project:

Since May 2011 I have been collecting material which points towards new ways of seeing the world, an echo of the society, technology, politics and people that co-produce them. The New Aesthetic is not a movement, it is not a thing which can be done. It is a series of artefacts of the heterogeneous network, which recognises differences, the gaps in our overlapping but distant realities.

Bruce Sterling described James as ‘a Walter Benjamin critic in an “age of digital accumulation”’ carrying out ‘a valiant cut-and-paste campaign that looks sorta like traditional criticism, but is actually blogging and tumblring.’ His site is well worth a visit, not least to wander through the back catalogue of objets trouvés (or vues):

I say ‘objet’ deliberately: for Graham Harman fans, and even for those who aren’t, there are some remarkably interesting discussions that link the New Aesthetic to object-oriented ontology: see Ian Bogost, ‘The New Aesthetic needs to get weirder‘ (not as weird as the cutesy title suggests), Robert Jackson, ‘The banality of the new aesthetic‘ (a really helpful essay for other reasons too) and Greg Borenstein, ‘What it’s like to be a 21st century thing‘ (scroll down – much more there too).

I started to follow the blog while I was working on a contribution to a conference on the Arab Uprisings [‘the Arab Spring’] held in Lund earlier this year: I’d been puzzled at the polarizing debate about whether (in the case of Tahrir Square in Cairo which most interested me, but much more generally too) whether this was ‘a Twitter revolution’ or whether it depended on what Judith Butler called (in a vitally important essay on the politics of the street to which I’ll return in a later post) ‘Bodies in Alliance‘. It seemed clear to me – and to her, as I discovered in a series of wonderfully helpful conversations when she visited Vancouver for the Wall Exchange in May) – that this was a false choice: that the activation of a digital public sphere was important, but so too, obviously, was the animation of a public space, and that the two were intimately – virtually and viscerally – entangled.

Here (in part) is what I wrote:

Writing from Cairo in March 2011, Brian Edwards recalled that when the Internet was blocked ‘the sense of being cut off from their sources of information led many back out on to the street, and especially to Tahrir. With the Internet down, several told me, there was nowhere else to go but outdoors.’ The reverse was also true. ‘The irony of the curfew is that it might succeed in getting people off the streets and out of downtown, but in doing so it delivers them back to the Internet… Many of my friends are on Facebook through the night, as are those I follow on Twitter, a steady stream of tweets and links. Active public discussions and debates about the meanings of what is taking place during the day carry on in cyberspace long after curfew.’

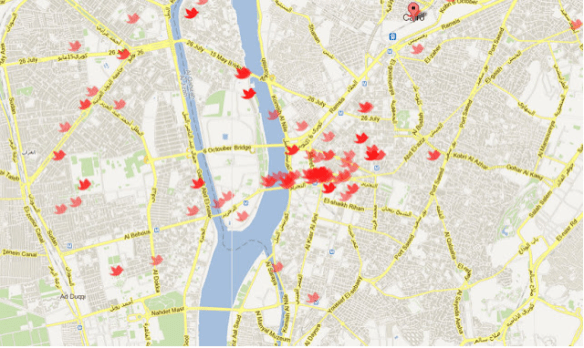

In the same essay Edwards reflects on the compression of meaning imposed by the 140-character limit of each tweet, and he suggests that the immediacy and urgency that this form implies – even imposes – ‘calls forth an immediate, almost unmediated response, point, counterpoint and so on.’This is a persuasive suggestion, I think, but that response is surely to be found not only virtually (from tweets in cyberspace) but also viscerally (from bodies in the streets). When we see maps … showing tweets in Cairo, we need to recognize that that these are not merely symbols in cartographic space or even messages in cyberspace: they are also markers of a corporeal presence.

This matters because the urban space where ‘newness’ might enter the world does not pre-exist its performance. Some writers examine what, following Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey, we might call the production of space, which would include the construction and re-development of Tahrir Square. Others, also following in some part Lefebvre, prefer to emphasize spatial practices, which would include the rhythms and routines that compose everyday life for a myriad of people in Cairo. But to emphasize the performance of space is to focus on the ways in which, as Judith Butler put it in direct reference to Tahrir Square, ‘the collective actions [of the crowd] collect the space itself, gather the pavement, and animate and organize the architecture.’

The virtual world is being integrated with the physical world and this seamlessness is presented as inherently good. No harm may be intended: it’s natural for a designer to want to smooth away the edges and conceal the joins. But in making these connections invisible and silent, the status quo is hard-wired into place, consent is bypassed and alternatives are deleted. This is, if you will, the New Anaesthetic. Instances of the New Aesthetic are often places where a glitch has exposed the underlying structure — the hardware and software. Or it is an oddity that has the unintended side effect of causing us to consider that structure. Part of a plane appearing in Google Maps makes us realise that we are looking at a mosaic of images taken by cameras far above us. We knew that already, right? Maybe we did. But a reminder may still be salutary.

This is political. The New Aesthetic was accused of being apolitical — fascinated by the oddities and wonders being thrown up by drones and surveillance cameras without thinking about the politics behind them. This is plain wrong: politics seeps from nearly every pore of the New Aesthetic. It was often hard to see, but that’s what Bridle wanted to expose.

The question is one of viewpoint. ‘As soon as you get CCTV, drones, satellite views and maps and all that kind of stuff,’ Bridle said, ‘you’re setting up an inherent inequality in how things are seen, and between the position of the viewer and the viewed. There are inherent power relations in that and technology makes them invisible. When you have a man in a watchtower, you look up at him, and that’s an obvious vision of power. When the man is in a bunker far away and you have just a little camera on a stalk … most people seem to be fine with that.’

The New Aesthetic is about seeing, then. And to see and be seen is to engage in those power relations.

More to come – watch this space….