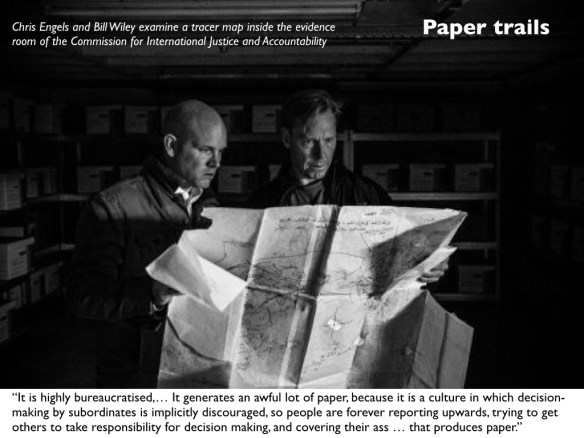

Apologies for the long silence – I’ve made several trips to the UK to deliver lectures, but I’ve also been (almost literally) in the trenches. My supposed-to-be 8,000 word essay on ‘Woundscapes of the Western Front’ has morphed into a monster: 35,000 words and I’m still not done…. More on that eventually (I so hope…). But en route, and in part as a response to a question I was asked after one of my presentations, I want to elaborate on a footnote.

My essay is about the evacuation of wounded soldiers, but human bodies were not the only ones requiring medical attention on the Western Front. By August 1917 the British Army had 368,000 horses and 82,000 mules in Belgium and France. At the outbreak of the war the cavalry were expected to play their traditional role –

[Image: National Library of Scotland]

– but by the end of the war most horses were pulling gun limbers, ammunition trains, supply waggons and ambulances [more here].

Horse-drawn ambulances were never made obsolete by motor ambulance convoys. Their capacity was limited and they were very slow – ‘hopelessly immobile’, according to one senior RAMC officer – but they remained the only option in some places. On the Somme in July 1916 the ground was so pitted with shell-holes that motor ambulances could not be used close to the line and horse ambulances worked for 24 hours or more at a stretch, ferrying casualties to motor ambulance convoys waiting further back:

Not surprisingly, horses (and mules) were highly vulnerable to shelling and shrapnel, to gas attacks and, wherever environmental conditions deteriorated, to injuries from traversing near-impossible terrain:

There is a haunting scene in Erich Maria Remarque‘s All quiet on the Western Front:

‘The cries continued. It is not men, they could not cry so terribly.

“Wounded horses,” says Kat.

It’s unendurable. It is the moaning of the world, it is the martyred creation, wild with anguish, filled with terror, and groaning….

They’ve got to get the wounded men out first,’ says Kat. We stand up and try to see where they are. If we can actually see the animals, it will be easier to cope with. Meyer has some field glasses with him. We can make some bigger things, black mounds that are moving. Those are the wounded horses. But not all of them. Some gallop off a little way, collapse, and then run on again. The belly of one of the horses has been ripped open and its guts are trailing out. It gets its feet caught up in them and falls, but it gets to its feet again. Detering raises his ri e and takes aim. Kat knocks the barrel upwards. ‘Are you crazy?’ Detering shudders and throws his gun on the ground. We sit down and press our hands over our ears. But the terrible crying and groaning and howling still gets through, it penetrates everything. We can all stand a lot, but this brings us out in a cold sweat. You want to get up and run away, anywhere just so as not to hear that screaming any more. And it isn’t men, just horses.

Yet far more equine losses were attributed to disease than enemy action, in contrast to troop losses (the First World War was the first in which deaths from wounds exceeded deaths from disease by a ratio of 2:1). One driver had a simple explanation. ‘Owing to the importance of the horses, whose lives were of greater value than those of the men, the horse-lines were usually in places free, or practically free from “strafing”’: Charles Bassett, Horses were more valuable than men (London: PublishNation, 2014) p. 65.

The horse-lines were indeed in the rear (see the remarkably pastoral image below: Glisy, on the Somme), but the nature of their work ensured that horses and mules had to be taken right up to the fire zone; between 1914 and 1916 battle losses accounted for 25 per cent of equine deaths, and they soared thereafter.

Last year Philip Hoare described these animals as ‘the truly forgotten dead.’ He continued: ‘Sixteen million animals “served” in the first world war – and the RSPCA estimates that 484,143 horses, mules, camels and bullocks were killed in British service between 1914 and 1918.

Yet, just as with human bodies, the toll of the equine dead overlooks that of the wounded. In response to the military importance of horses and mules, the (Royal) Army Veterinary Corps [the ‘Royal’ prefix was granted immediately after the war] established a system of veterinary medicine parallel to the casualty evacuation system of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

The equivalent of the Field Ambulance was the Mobile Veterinary Section; animals needing more extensive emergency care were transferred to Veterinary Evacuation Stations (the equivalent of the Casualty Clearing Station) located at railheads. They were moved either by horse-drawn ambulance –

– or by special motor ambulances designed to carry two horses each (there were 26 of them, donated by the RSPCA and subscribed from public donations):

Like wounded soldiers, horses needing further medical or surgical attention were transported by barge (mainly in Flanders: each barge could carry 32 animals) –

– or by rail to Veterinary Hospitals at the base on the French coast.

In the first months of the war cattle trucks on supply trains returning empty to the base were used (here too the parallels with the evacuation of wounded soldiers are exact!) but once the Veterinary Evacuating Stations had been established special horse trains were introduced. These had to be more or less self-sufficient: supplies of water were especially vital. Major-General Sir John Moore emphasised: ‘In transporting sick and enfeebled animals, particularly by train, which during hot seasons of the year is very exhausting, the greatest care must be exercised in watering and feeding en route.’ The need was compounded by the slow and often circuitous journeys made by trains that – like the ambulance trains carrying wounded soldiers – always had to yield to troop trains and supply trains rushing up to the front.

Between 18 August 1914 and 23 January 1919 over half a million sick and wounded animals passed through the British Army’s Mobile Veterinary Sections and Veterinary Evacuating Stations in Flanders and France. On average a special train carrying 100 sick or injured horses would arrive twice a day at each Veterinary Hospital; between 2,500 and 3,500 horses were admitted to hospital each week, and at their peak more than 4,500 were being cared for at any one time.

The capacity of these hospitals was originally set at 1,000 animals, but this was subsequently doubled. It was not uncommon, Moore explained, ‘to see three animals in the operating theatre under chloroform at the same time.’

Very few animals were allowed to stay more than three months at the base, where the hospitals operated in conjunction with Convalescent Horse Depots.

According to Moore, the core principle of the Army Veterinary Corps was ‘to get down from the front as many animals as it was possible to save; in other words to give every animal a chance.’ But what lay behind this was the same instrumentalism that guided the RAMC’s casualty evacuation model and its system of triage: the need identify the casualties most likely to survive in short order and to treat them expeditiously so that they could be returned to the front and the fight.

***

You can find more from these sources:

- Simon Butler, The war horses (Halsgrove, 2011);

- Stephen Corvi, ‘Men of Mercy: the evolution of the Royal Army Veterinary Corps and the soldier-horse bond during the Great War,’ Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 76 (308) (1998) 272-84;

- M-G Sir John Moore, Army Veterinary Service in War (London: Brown, 1921) [available here]

- Rachael Passmore, ‘The care, development and importance of the British horse on the Western Front in World War I,’ MA thesis, Department of History, University of Leeds, 2009 [accessible here];

- John Singleton, ‘Britain’s military use of horses 1914-1918’, Past & Present 139 (1993) 178-203.

Like my original essay, this post is confined to the British Army; for a remarkably detailed and beautifully illustrated account of the veterinary medical system of the US Army on the Western Front see here.

Unless otherwise credited, ALL IMAGES are Copyright Imperial War Museum, London

A special issue of Media, War and Conflict has just appeared, guest-edited by Katharina Niemeyer and Staffan Ericson, devoted to media and terrorism in France:

A special issue of Media, War and Conflict has just appeared, guest-edited by Katharina Niemeyer and Staffan Ericson, devoted to media and terrorism in France: