‘He straightened and held me in one hand. “Right, orders for tomorrow’s operation,” he said. “We’re deploying most of the company for the first time and the whole platoon’s out together. It’s a standard route security operation for the logistics convoy bringing in our supplies. There’s nothing complicated about this patrol, but we’ll be static for long periods and that will make us vulnerable. We have to clear all the roads in our AO and then secure it so the convoy can travel safely through.” He moved his hand up my shaft and used me to point at the flat ground.

“Is everyone happy with the model?” he said.

There were a few silent nods from the watching men.

“Just to orientate you again. This is our current location.” He pointed me at a tiny block of wood near the centre of the grid that had PB43 written on it in peeling blue paint. It was the largest of a hundred little wooden squares placed carefully across the earth and numbered in black. “This is Route Hammer.” He moved my end along a piece of orange ribbon that was pinned into the dirt. “And this blue ribbon represents the river that runs past Howshal Nalay.” I swept along the ribbon over a denser group of wooden blocks. “These red markers are the IED finds in the last three months, so there’s quite a few on Hammer.” I hovered over red pinheads…

He started describing the plan and used me to direct their attention to different parts of the square. He said their mission was to secure the road and then provide rear protection. He told them how they would move out before first light and push along the orange ribbon, past the blocks with L33 and L34 written on them. I paused as he explained how vulnerable this point was, and that one team would provide overwatch at the block marked M13 while others cleared the road.

I was pointed at one of the men, who nodded that he understood.

He told them how they would spread out between block L42 and the green string. Two other platoons would move through them and secure the orange ribbon farther up. Then he swept me over the zones they were most likely to be attacked from. He said the hardest part of the operation was to clear the crossroads at the area of interest named Cambridge; this was 6 Platoon’s responsibility. I hovered over where the orange ribbon was crossed by white tape.

I had done it all before: secured sections of the ribbon, dominated areas of dirt, reassured little labels, ambushed red markers and attacked through clusters of wooden blocks. I had destroyed as my end was pushed down hard and twisted into the ground. I’d drawn lines in the sand that were fire-support positions and traced casualty evacuation routes through miniature fields. I was master of the model.’

This passage comes from Harry Parker‘s stunning novel about the war in Afghanistan, Anatomy of a soldier (Faber, 2016).

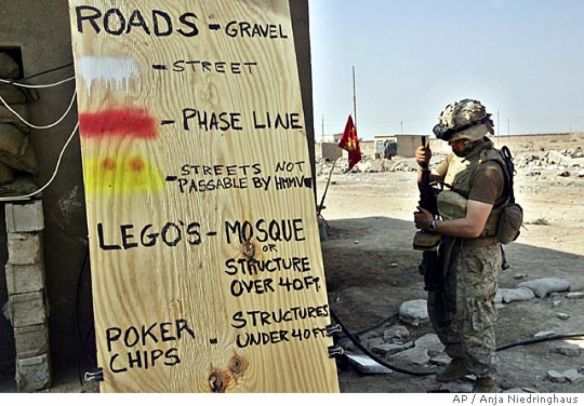

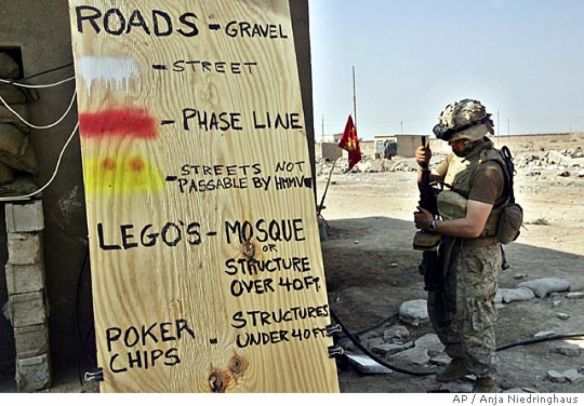

In one sense, perhaps, it’s not so remarkable: the use of improvised physical models to familiarise troops with the local terrain is a commonplace even of later modern war. In ‘Rush to the intimate‘ (DOWNLOADS tab) I described how in November 2004, immediately before the second US assault on Fallujah, US Marines constructed a large model of the city at their Forward Operating Base, in which roads were represented by gravel, structures under 40′ by poker chips and structures over 40′ by Lego bricks (see image below). Infantry officers made their own physical model of the city using bricks to represent buildings and spent shells to represent mosques.

I called this a ‘rush from the intimate to the inanimate’, and discussed the ways in which the rendering of the city as an object-space empty of life was a powerfully performative gesture – one in which, as Anne Barnard put it, the soldiers straddled the model ‘like Gulliver in Lilliput’.

As the passage I’ve just quoted suggests, it was standard practice in Afghanistan too; here are soldiers from the Afghan National Army studying a model for Operation Tufan/Storm, a joint ANA/UK operation in Helmand:

So far, then, so familiar. But the passage with which I began is remarkable because the narrator – whose shaft is gripped by the officer’s hand, who hovers over the orange ribbon, who confesses to having done it all before – is the handle of a broken broom. ‘My first purpose was to hold my head down against the ground as I brushed sand out of a small, dirty room,’ the chapter begins. ‘In time, my head loosened and the nail then held it on pulled free. Someone tried to push it back on, but my head swung round and fell off. I was discarded.’

‘That would have been the end of me,’ the broom handle continues – ‘my head was burned with the rubbish’ – ‘but I was reinvented and became useful again.’

The novel tells the story of Captain Tom Barnes, a British army officer who steps on an IED while on patrol in Afghanistan; he is airlifted to the Role 3 hospital at Camp Bastion and then evacuated to Britain; he loses both his legs, the first to the effects of the blast and the second to infection. And the narrative is reconstructed through the objects that are entangled in – and which also, in an extraordinarily powerful sense, animate – the events.

So, for example, a tourniquet:

‘My serial number is 6545-01-522… A black marker wrote BA5799 O POS on me and I was placed in the left thigh pocket of BA5799’s combat trousers… At 0618 on 15 August, when I was sliding along BA5799’s thigh, I was lifted into the sky and turned over. And suddenly I was in the light… I was pulled open by panicked fingers and covered in the thick liquid… I was wound tighter, gripping his thigh… I clung to him as we flew low across the fields and glinting irrigation ditches…’

The story is continued in and through other object-fragments. On patrol, a boot; day-sack; helmet (‘My overhanging rim cut his vision as a black horizontal blur and my chinstrap bounced up against his stubble as he pounded onto each stride’); night vision goggles (‘My green light reflected off the glassy bulge of his retina’); a radio (‘His breathing deepened under the weight of the kit and condensation formed on the gauze of my microphone… I continued to play transmissions in BA5799’s ear as the other stations in the network pushed farther up the road’); an aerial photograph (‘He took me out and traced his finger across my surface… in the operations room a small blue sticker labelled B30 was moved across a map pinned to the wall. That map was identical to me’); and his identity tags (‘I had dropped around your neck and my discs rested on the green canvas stretcher stained with your blood’).

After the blast from the IED and a helicopter evacuation, the medical apparatus: a tube inserted into his throat at Camp Bastion’s trauma centre (‘I was part of a system now; I was inside you…’); a surgical saw (‘He held me like a weapon, and down at the end of my barrel was my flat stainless-steel blade… My blade-end cut through the bone, flashing splinters and dust from the thin trench I gouged out’); a plasma bag (‘I hung over you… I was empty; my plastic walls had collapsed together and red showed only around my seals. The rest of the blood I’d carried since a young man donated it after a lecture, joking with a mate in the queue, was now in you’); a catheter; a wheelchair; his series of prosthetics (‘You pressed your stump into me and we became one for the first time… Slowly you outgrew all my parts and the man switched them over until I only existed as separate components in a cupboard and you’d progressed to a high-activity leg and a carbon-fibre socket’).

The agency of many of the objects is viscerally clear:

‘I lived in the soil. My spores existed everywhere in the decomposing vegetable matter of the baked earth. Something happened that meant I was suddenly inside you… I was inside your leg, deep among flesh that was torn and churned. I lived there for a week and wanted to take root, but it wasn’t easy… I struggled to survive. Except they missed a small haematoma that had formed around a collection of mud in your calf… You degraded and I survived… I made you feverish and feasted unseen on your insides…’

Or again, his first prosthetics:

‘You improved on me but you became thinner. The pressure I exerted on you, and the weight you lost from the energy I used, made your stump shrink. I could no longer support you properly.’

And the new ones:

‘Your hand caressed my grey surface and felt around the hydraulic piston under my knee joint… You’d been waiting for me but were nervous about what I might do for you…’

What is even more remarkable, as many of the passages I have quoted demonstrate, is that these events are narrated through objects that in all sorts of ways show how military violence reduces not only the ground but the human body to an object-space, perhaps nowhere more clearly than in this remark: ‘You were not a whole to them, just a wound to be closed or a level on a screen to monitor or a bag of blood to be changed.’ And yet: virtually every one of those passages is also impregnated with Barnes’s body: its feel – its very fleshiness – its sweat, its smell, its touch.

I think this is an even more successful attempt to render the corporeality of war through its objects than Tim O’Brien‘s brilliant account of Vietnam in The Things They Carried (for more, see my post on ‘Boots on the Ground‘ and my essay on ‘The natures of war’: DOWNLOADS tab). This is, in part, because the narrative is not confined to those objects close to Barnes’ own body; it spirals far beyond them to include a drone providing close air support (‘I banked around the area and my sensor zoomed out again and I could see the enemy in relation to the soldiers who needed me’) and, significantly, extends to the components of the IED and the bodies of the insurgents who constructed and buried it.

I think this is an even more successful attempt to render the corporeality of war through its objects than Tim O’Brien‘s brilliant account of Vietnam in The Things They Carried (for more, see my post on ‘Boots on the Ground‘ and my essay on ‘The natures of war’: DOWNLOADS tab). This is, in part, because the narrative is not confined to those objects close to Barnes’ own body; it spirals far beyond them to include a drone providing close air support (‘I banked around the area and my sensor zoomed out again and I could see the enemy in relation to the soldiers who needed me’) and, significantly, extends to the components of the IED and the bodies of the insurgents who constructed and buried it.

There is a powerful moment when the two collide, when the father of a young insurgent killed in the drone strike wheels his son’s body to the patrol base:

‘The corpse was half in me, with my front end under it and my handles sticking up in the air. He managed to push it farther into me and the distended head bounced off my metal side. Dried blood showed around its ears and nose and was red in its mouth. And then he pushed my handles down and I scooped it all up… The corpse’s eyes had opened from the jolting and looked up at him. He looked down into them, at his son’s face and the blue lips and purple blotching across his cheeks and he knew he had already accepted the loss. He lowered my handles and smoothed the eyelids shut again. He pushed me down the road.’

Barnes reaches for a compensation form, which takes up the story:

‘There was a leaflet that BA5799 had read tucked in the notebook next to me. It described how to deal with this. What to say, what not to say… He was dealing with death in an alien culture and he had no idea how to relate to this man or the death of his son… BA5799 wanted to feel compassion for this man and his dead son but only felt discomfort and the man’s eyes challenging him. And all he cared about was getting back into the base and the loss of a potential asset in securing the area.’

All of these criss-crossing, triangulating lines capture not only the anatomy of a soldier but an anatomy of the war itself – at once calmly, coolly and shockingly abstract – in a word, objectified – and invasively, terrifyingly, ineluctably intimate.

***

Postscript: You probably won’t be surprised to learn that Anatomy of a soldier is based on Harry Parker’s own experience. Out on patrol with his men on 18 July 2009 in central Helmand he stepped on an IED; he lost his lower left leg in the blast and had his lower right leg amputated at Selly Oak Hospital in Birmingham (the major centre for advanced trauma care for the British military). ‘‘Writing about the explosion felt good creatively,’ he told Christian House, ‘but also you’ve mined your personal experiences’ and the process left him ‘a sweaty mess’. I’ve written about what Roy Scranton calls ‘the trauma hero‘ before, and so it’s important to add that Parker insists that the novel is not disguised autobiography: ‘I didn’t want to write, “I was in the Helmand valley.”’

Postscript: You probably won’t be surprised to learn that Anatomy of a soldier is based on Harry Parker’s own experience. Out on patrol with his men on 18 July 2009 in central Helmand he stepped on an IED; he lost his lower left leg in the blast and had his lower right leg amputated at Selly Oak Hospital in Birmingham (the major centre for advanced trauma care for the British military). ‘‘Writing about the explosion felt good creatively,’ he told Christian House, ‘but also you’ve mined your personal experiences’ and the process left him ‘a sweaty mess’. I’ve written about what Roy Scranton calls ‘the trauma hero‘ before, and so it’s important to add that Parker insists that the novel is not disguised autobiography: ‘I didn’t want to write, “I was in the Helmand valley.”’

One other note: at the AAG meeting in San Francisco next month Iain Shaw and Katherine Kindervater have organised a series of really interesting sessions on Objects of Security and War:

These sessions aim to bring together scholars working in the areas of war and security that are attentive to the materialities of contemporary violence and conflict. We are especially interested in work that seeks to place objects of security and war within a wider set of practices, assemblages, bodies, and histories. From drones and documents, to algorithms and atom bombs, the materiality of state power continues to anchor and disrupt the conduct and geography of (international) violence.

I’m part of those sessions – but reading Anatomy of a soldier has made me think about giving an altogether different presentation. I’ve long argued that we need to disrupt that lazy divide between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ and that literature is able to convey important truths that evade conventional academic prose (hence my unbounded admiration for Tom McCarthy‘s C, for example). And Anatomy of a soldier convinces me that I’ll find more inspiration in novels like that than in whole libraries on object-oriented philosophy…

As military and paramilitary attacks on hospitals and medical facilities have increased – in Afghanistan, Gaza, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere – even as the number of casualties has soared, Michael VanRooyen‘s new book The World’s Emergency Room (out next month from St Martin’s) promises to provide an urgent overview of what has become a routinised violation of medical neutrality:

As military and paramilitary attacks on hospitals and medical facilities have increased – in Afghanistan, Gaza, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere – even as the number of casualties has soared, Michael VanRooyen‘s new book The World’s Emergency Room (out next month from St Martin’s) promises to provide an urgent overview of what has become a routinised violation of medical neutrality: