I was in Warsaw over the week-end, and my visit coincided with the opening of the new building for the Museum of the History of Polish Jews on the 70th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Even in its presently empty state, it’s a stunning place.

Its Core Exhibition, developed under the supervision of Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, will display the thousand-year history of Jews in Poland, but the Museum has been built on the site of a pre-war Jewish neighbourhood where in October-November 1940 the Germans established the largest Jewish ghetto in Nazi-occupied Europe and razed it to the ground less than three years later. And it’s this recent catastrophe (along with others) that invests so much of Warsaw with its contemporary historicity.

You can find a sequence of other chilling maps of the Ghetto (and a helpful critical discussion of them) here, basic accounts of the process of its formation here, an excellent summary survey of the Uprising here and a shorter one here. By 1943 hundreds of thousands of Jews had been deported from the Ghetto to concentration camps, and according to Deutsche Welle:

In early 1943, Heinrich Himmler ordered the final liquidation of the ghetto. Until then, most Jews had rejected armed resistance, including for religious reasons. But when the last mass deportation was about to begin, hundreds of young Jews decided to fight.

On April 19, 1943, the approaching German units met unexpected resistance. The young Jews were aware of their hopeless situation – they had no weapons, food or support. Yet they endured for three weeks, delivering a fierce battle. When the Germans surrounded the insurgents’ bunker in early May, they collectively committed suicide.

“They wanted to decide themselves how to die,” said Zygmunt Stepinski, director of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw. He called their deaths a political manifesto. “They wanted to show that Jews could defend themselves and that they organized the first-ever uprising against the Nazis,” he said.

13,000 Jews were killed during the Uprising, and most of the surviving 50,000 were deported to concentration and extermination camps.

The Museum has been designed by a Finnish architect, Rainer Mahlamäki, and his studio. To some degree, in its bridge suspended over the Main Hall, defined by the soaring, undulating walls that divide the Museum into its two parts, the building reinscribes the division of the ghetto into two and the bridge that joined the one to the other (over Chlodna Street, an ‘Aryan’ thoroughfare), but more significantly it’s intended as ‘a bridge across the chasm created by the Holocaust – a bridge across time, continents and people.’

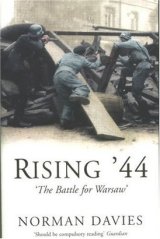

Many of those involved in the Museum project have suggested that the 1943 Uprising was a crucial inspiration for the general Warsaw Rising in 1944. This started on 1 August, and the insurgent Polish Home Army held out for 63 days of intensive urban warfare which left 16,000 of them dead along with 150-200,00 civilians. The best English-language narrative of these courageous and horrifying events is probably Norman Davies‘s Rising ’44.

Many of those involved in the Museum project have suggested that the 1943 Uprising was a crucial inspiration for the general Warsaw Rising in 1944. This started on 1 August, and the insurgent Polish Home Army held out for 63 days of intensive urban warfare which left 16,000 of them dead along with 150-200,00 civilians. The best English-language narrative of these courageous and horrifying events is probably Norman Davies‘s Rising ’44.

To make sense of this on the ground and to recover its material traces, we turned to the Warsaw Rising Museum, which included City of Ruins, an extraordinary 3-D simulation of American Liberator flights over the city in 1945 (advertised as the world’s first digital stereoscopic simulation of a city destroyed during the war: more on the project and how it was achieved here) –

– and to an outdoor/indoor exhibition of colour photographs of the ruined city taken by a young American architectural student, Henry N. Cobb, in 1947: The Colors of Ruin. You can see some of Cobb’s photographs here, and Vimeo has this interview with him which includes a number of incredible images too:

Why such wholesale destruction? Under the terms of the surrender document agreed by the Polish Home Army in October 1944, the insurgents and the civilian population were expelled from the city into transit camps, from where they were deported to concentration camps. According to some accounts, Hitler issued Command #2 on 11 October, realizing his pre-war dream of the total destruction of the city: ‘Warsaw is to be razed to the ground while the war proceeds.’ Six days later Himmler made sure his officers understood exactly what was intended:

‘The city must completely disappear from the surface of the earth… No stone can remain standing. Every building must be razed to its foundation.’

Special Verbrennungskommandos (‘annihilation detachments’) began the systematic destruction of what was left of the city with mathematical precision, using high explosives and flame-throwers. According to the Museum guide,

‘They divided the city into regions, numbered the corner buildings and methodically destroyed the capital. On the walls they put instructions concerning the method of destruction. The Germans destroyed historical monuments and burned to ashes the biggest Polish libraries… They turned archives, museums and their collections into ruins and ashes. The Old Town became a city of ruins.’

Less than 5 per cent of pre-war Warsaw remained intact – about 12 per cent had been totally destroyed during the 1939 bombing and siege of the city, a further 17 per cent with the destruction of the Ghetto and 25 per cent during the Rising of 1944 – but it’s the systematicity as much as the scale that is so shocking. And the sense of shock remains even as – in fact precisely because – today you walk around an Old City no less painstakingly restored, its planners, architects and builders working from old plans, photographs and drawings and using the original materials as far as possible. It adds another dimension to what Steve Graham calls the post-mortem city: the resurrection of Warsaw is an extraordinary testimony (like the Museum of the History of Polish Jews) to the determination of a people to recover their history, to refuse their erasure, and to remember the enormity of what befell their predecessors.

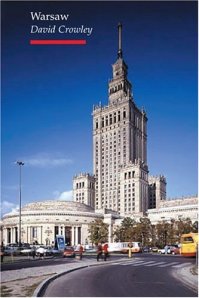

Or so it seemed to me before I started to think (and read) about the politics of memorialisation in post-war Warsaw. David Crowley‘s essay on ‘Memory in Pieces: the symbolism of the ruin in Warsaw after 1944’ argues that

‘the image of ruin … functioned – unmistakably – as an ideological vent through which to draw patriotic sentiment and indict those who had destroyed the city. But the powerfully affective image of ruin and the memories that it could arouse had to be contained and its force channelled (quite literally, in the form of voluntary labour to reconstruct parts of the city, like the Old Town). In effect ruins, in the representational cosmos of socialism during the 1950s, were time-locked in 1944, the moment of destruction.’

But what could the Royal Palace (in particular) re-present within that cosmos? Tellingly, it was still in ruins in 1956 when a post-Stalinist regime came to power, and existing plans for its reconstruction were abandoned. ‘In the years that followed,’ Crowley writes, ‘the castle formed an open wound at the heart of the city. Seeing it as an aristocratic symbol of democracy, Crowley calls it an ‘architectural oxymoron.’ In ruins, the castle could ‘function indexically as evidence of both the glorious Polish past and the ignominious “Soviet” present.’ Finally, in the 1970s its reconstruction was approved as ‘Warsaw Castle’, an attempt to extinguish the aristocratic past and to forestall any democratic future, so that it functioned as what Crowley calls a sort of counter-iconoclasm, working to forget what its absence once signified.

But what could the Royal Palace (in particular) re-present within that cosmos? Tellingly, it was still in ruins in 1956 when a post-Stalinist regime came to power, and existing plans for its reconstruction were abandoned. ‘In the years that followed,’ Crowley writes, ‘the castle formed an open wound at the heart of the city. Seeing it as an aristocratic symbol of democracy, Crowley calls it an ‘architectural oxymoron.’ In ruins, the castle could ‘function indexically as evidence of both the glorious Polish past and the ignominious “Soviet” present.’ Finally, in the 1970s its reconstruction was approved as ‘Warsaw Castle’, an attempt to extinguish the aristocratic past and to forestall any democratic future, so that it functioned as what Crowley calls a sort of counter-iconoclasm, working to forget what its absence once signified.

But there was another, more pervasive absence. The razing of the Ghetto destroyed a significant nineteenth-century fabric, and after the war a still wider nineteenth-century Warsaw disappeared from the landscape of reconstruction altogether. Jerzy Elzanowski argues that its buildings and structures were seen as emblematic of the repressive class structure of capitalism; they had to be replaced by a radically different fabric ‘adequate to the needs of socialist society’ (‘Manufacturing ruins: architecture and representation in post-catastrophic Warsaw’, Journal of Architecture 15 (1) (2010) 71-86).

And there are, of course, other, ostentatiously modern Warsaws that have been forcibly put in place after the fall of Communism in 1989.

And there are, of course, other, ostentatiously modern Warsaws that have been forcibly put in place after the fall of Communism in 1989.

For all that, in the city of ruins, and most of all in the spectral traces of the two war-time uprisings in which images are made to stand for ruins, genocide and urbicide march in lockstep: and we would be foolish not to attend to the sounds and signs of their boots on the street. Crowley thinks their museumisation and memorialisation is a kind of reversal in which the past (and specifically the Second World War) becomes a ‘lost utopia’. I see what he means – I saw what he means – and I’m beginning to understand, too, why Elzanowski concludes that, at least in Warsaw (and no doubt elsewhere), images are at once indispensable for historical recovery and yet ‘seem to hinder our ability to observe the reality of here and now.’ It was, in part, an unease about my response to the materiality of the city and to its photographic representations that sent me off to dig out their two essays. I felt a tension between the affective – the effect the ruins and the reconstructions had on me – and the analytical. I’m still struggling.