I returned from a wonderful visit to Glasgow last week – thanks so much to Jo Sharp, who ensured I had a criminally good time – and I’ve spent this week trying to catch up. It rained most of the time I was there, and in fact my first impression of the University was of a quadrangle turned into a quagmire: a case of mire in the flood, you might say. But nothing could dampen my spirits, and in the gaps between marvellous restaurants, coffee shops that would make anyone in Vancouver (or Seattle) green with envy, the best lunch ever, and truly excellent conversation, I gave two talks: one on my skeletal ideas about my new project on Medical-military machines and casualties of war, 1914-2014, and the other a more formal affair on ‘Dirty dancing: drone strikes, spaces of exception and the everywhere war.’ The purpose of the first talk was to explore, largely for graduate students, how I work; it generated a lively discussion, so I thought I would try to do the same in this post but in relation to the second presentation. And in doing so, I’ll also have more to say about the scene of a real crime.

I’d prepared my formal presentation before I left Vancouver, and as I’ve explained before I now never read from a written text: I design the slides carefully (see my ‘Rules’ here) and talk to them, so that I retain as much flexibility as possible. It’s a sort of semi-scripted improv, I suppose, and it also means that the argument can develop from one presentation to the next.

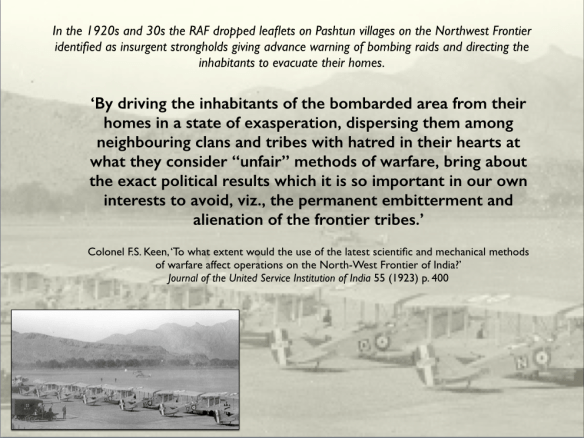

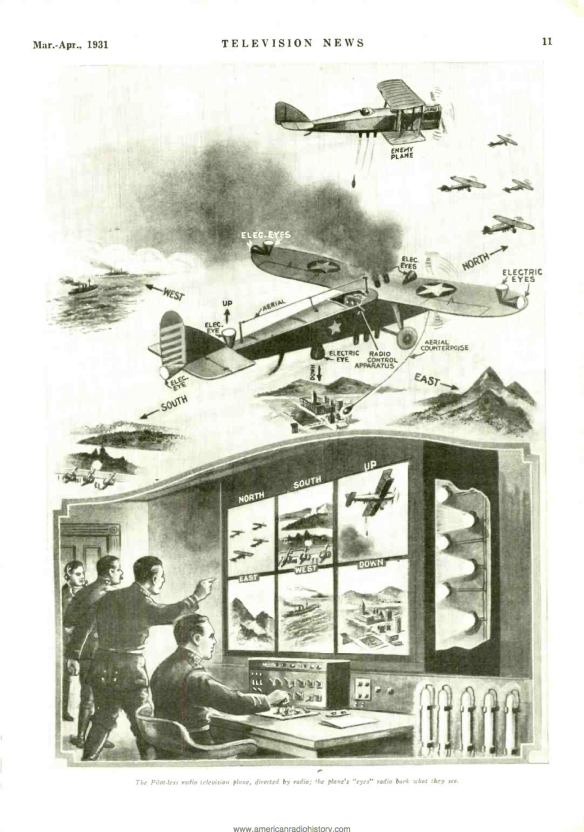

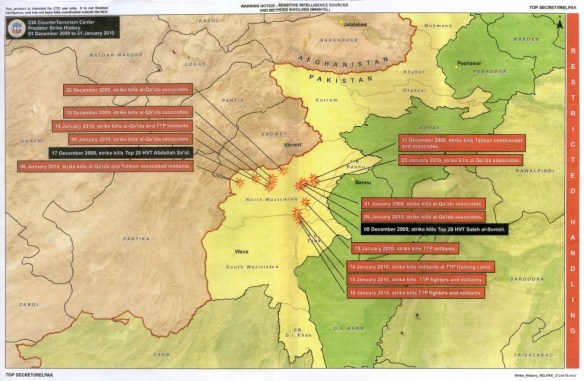

On the train up from London I started to think some more about the air strikes on the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (see also here, here and here). Part of my purpose was to trace a narrative of air attack that, for those now ‘living under drones’, stretched back (at least in memory) to British air control and counterinsurgency on the North West Frontier in the 1920s and the 1930s.

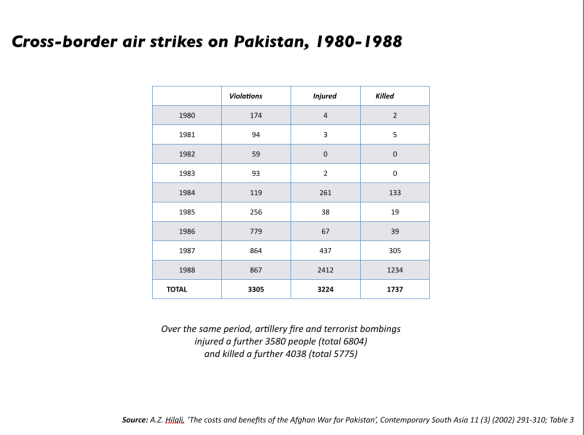

I’d made this point before, and sharpened it during an earlier version of the presentation in Beirut, but I’d since realised that the narrative was resumed by the Soviet and Afghan Air Forces striking mujaheddin bases in Pakistan during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. I hadn’t paid much attention to this in The colonial present, where my focus was on the aid provided by the CIA to mujaheddin striking across the border in the opposite direction, but these air raids were described by the Washington Post on 13 March 1988 as part of the USSR’s “war of terror” (really). They are an important moment in the genealogy of air strikes and counterinsurgency in the FATA, and I’d managed to unearth some estimates of the number of cross-border violations of Pakistani air space and the number skilled and injured in the strikes:

I’d made this point before, and sharpened it during an earlier version of the presentation in Beirut, but I’d since realised that the narrative was resumed by the Soviet and Afghan Air Forces striking mujaheddin bases in Pakistan during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. I hadn’t paid much attention to this in The colonial present, where my focus was on the aid provided by the CIA to mujaheddin striking across the border in the opposite direction, but these air raids were described by the Washington Post on 13 March 1988 as part of the USSR’s “war of terror” (really). They are an important moment in the genealogy of air strikes and counterinsurgency in the FATA, and I’d managed to unearth some estimates of the number of cross-border violations of Pakistani air space and the number skilled and injured in the strikes:

Then, in one of the ironic twists of our post 9/11 world, the (il)logic of air war was revived and ramped up by the CIA-directed drone strikes that have convulsed the borderlands since 2004.

I wanted to show, as I’ve argued in previous posts, that this narrative was more than a cross-border affair and that the Pakistan Air Force has been also actively involved in a series of domestic air campaigns: since 2008 it has carried out thousands of air strikes against what it describes as militants, insurgents and terrorists in the FATA. In fact, the offensive was resumed earlier this year, when F-16 aircraft and helicopter gunships attacked targets in North Waziristan, driving thousands of people from their homes.

In some measure, all of these air campaigns raise the spectre of colonial power, but so too does the legal status of the FATA and its exceptional relation to the rest of Pakistan. This is usually traced back to Lord Curzon’s Frontier Crimes Regulations (1901), which were retained by Pakistan after independence in 1947. They were minimally revised in 2011, but the FATA are still under the direct executive control of the President through his appointed Political Agents who have absolute authority to decide civil and criminal matters. The exceptional status of the FATA was confirmed by the Actions (in Aid of Civil Power) Regulations in 2011 which exclude the high court from jurisdiction on fundamental rights issues in any area where the Pakistan armed forces have been deployed ‘in aid of the civil power’.

In some measure, all of these air campaigns raise the spectre of colonial power, but so too does the legal status of the FATA and its exceptional relation to the rest of Pakistan. This is usually traced back to Lord Curzon’s Frontier Crimes Regulations (1901), which were retained by Pakistan after independence in 1947. They were minimally revised in 2011, but the FATA are still under the direct executive control of the President through his appointed Political Agents who have absolute authority to decide civil and criminal matters. The exceptional status of the FATA was confirmed by the Actions (in Aid of Civil Power) Regulations in 2011 which exclude the high court from jurisdiction on fundamental rights issues in any area where the Pakistan armed forces have been deployed ‘in aid of the civil power’.

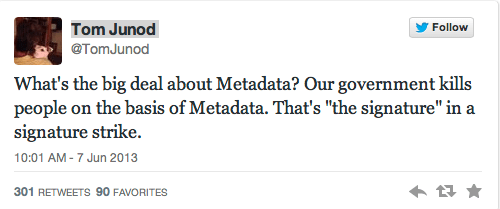

All of this indicates that the FATA constitute a ‘space of exception’ in something like Giorgio Agamben‘s sense of the term: a space in which particular people are knowingly exposed to death through the juridical or quasi-juridical removal of legal protections from them. This was, in part, my argument, but I was also concerned to show that this was not a matter of a legal void: rather, military and paramilitary violence was orchestrated, as it almost always is, through the law.

But there is quite another sense in which the FATA is not a legal void, despite all the rhetoric about them being ‘lawless’ lands. So I started to think through the intersections between these formal legal geographies (and the state violence they sanction) and the system of customary law known as Pashtunwali (loosely, “the way of the Pashtuns”). The system is far from static, but it still governs many areas of life among Pashtuns on both sides of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border whose cultures and communities were bisected when the Durand Line was drawn in 1893. I’d been reading as much as I could by anthropologists and others to help me understand its contemporary relevance: for recent surveys, see Tom Ginsburg‘s ‘An economic interpretation of the Pashtunwali’ from the University of Chicago Legal Forum (2011) here, Lutz Rzehak‘s ‘Doing Pashto’ here, and Thomas Ruttig‘s qualifications in relation to the Taliban here. For a sense of how the US military understands Pashtunwali, as part of its ‘cultural turn’, see Robert Ross‘s thesis here.

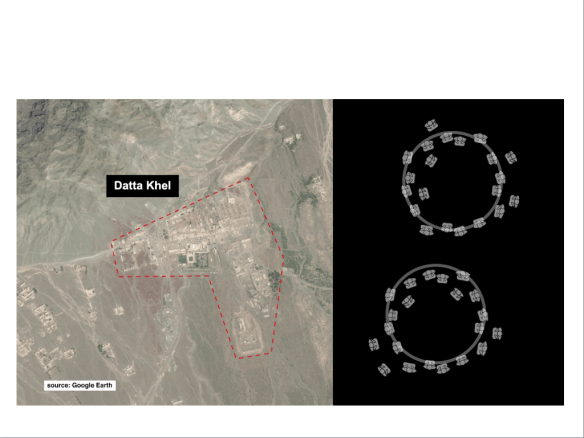

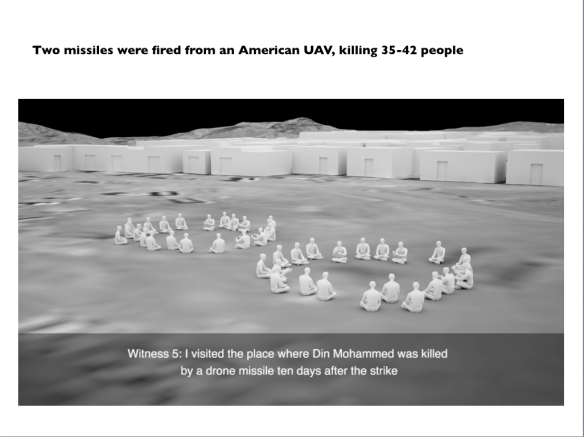

Pashtunwali is more than a legal system, of course, but I was particularly interested in its legal force and how this is put into practice. Many commentators have shown that Pashtunwali is precisely the sort of ‘mobile’ legal system that you would expect to find among (originally) nomadic peoples, for whom the fixed statutes of a centralised state had neither appeal nor purchase. It includes obligations of hospitality and protection, asylum and refuge, and revenge and restitution, and provides for a system of resolution through a council (or Jirga). Within its patriarchal and masculinist framework, the system is resolutely non-hierarchical: the men who compose the Jirga sit in a circle and each, as a symbol of authority and equality, carries a gun.

Sitting in a circle, the Jirga has no speaker, no president, no secretary or convener. There are no hierarchical positions and required status of the participants. All are equal and everyone has the right to speak and argue, although, regard for the elders is always there without any authoritarianism or privileged rights attached to it. The Jirga system ensures maximum participation of the people in administering justice and makes sure that justice is manifestly done.

On my way over to the UK I’d read an extremely interesting essay in the International Review of Law and Economics 37 (2014) 108-20 – stored on Good Reader on my iPad – in which Bruce Benson and Zafar Siddiqui argued that the system works not only to provide a decentralised, local and regional system of order and regulation – so Hobbes was wrong: without the state people do not automatically revert to a ‘state of nature’ (Tom Ginsburg is very good on this) – but also to defend the Pashtun from the incursions of the central state. Indeed, the Frontier Crimes Regulations specifically recognised the validity and autonomy of the Jirga: much more here. The message from all this was clear: ‘The Pashtun tribes who inhabit the rugged mountains between Afghanistan and Pakistan are neither lawless nor defenceless.’

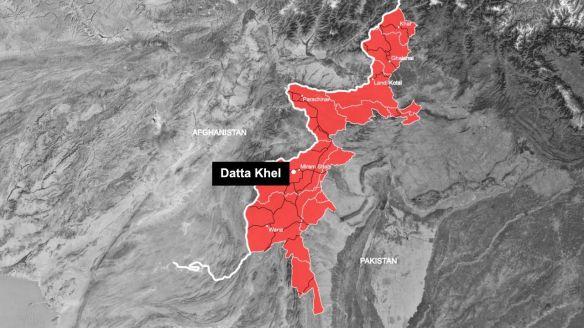

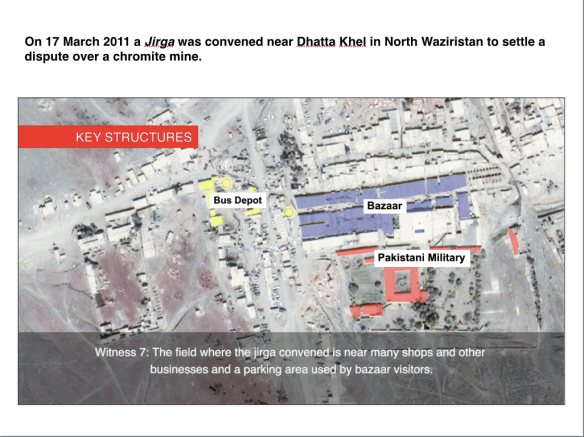

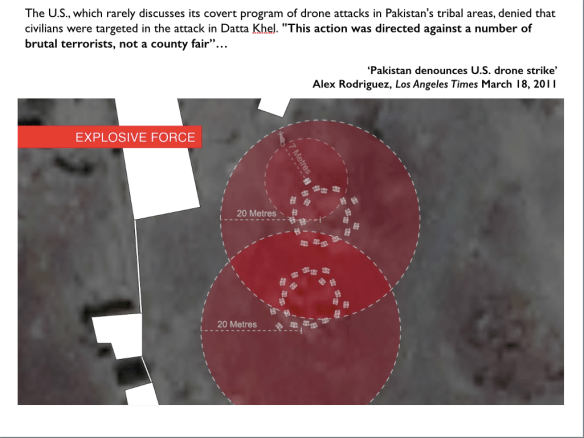

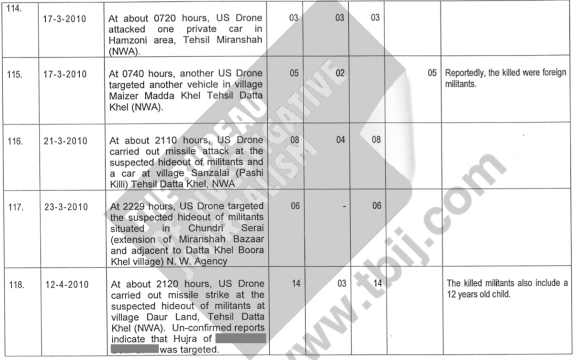

The Pakistan Taliban know this very well, not surprisingly, and in many instances work with Pashtunwali to mediate disputes in the FATA. In fact, as the train curved around the Lake District I remembered reading about a Jirga being convened in Datta Khel in March 2011 to resolve a dispute over a chromite mine. It’s odd how some things stick in your mind, like burrs on your jeans, but this incident had stayed with me because the Jirga had been targeted by the CIA and two Hellfire missiles were launched from a drone, killing more than 40 people. In itself, that probably wouldn’t have been enough for me to remember it in any detail since it was all too common – but the usual faceless and anonymous US official, speaking off the record because he was not authorised to comment in his official capacity, had offered a series of ever more bizarre justifications for the strike: and I remembered those (as you’ll see in a moment, you could hardly forget them).

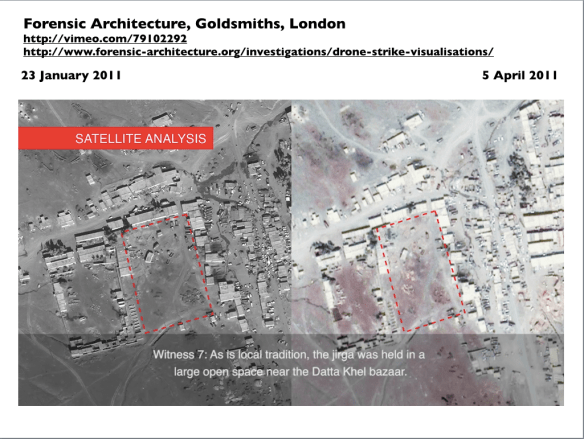

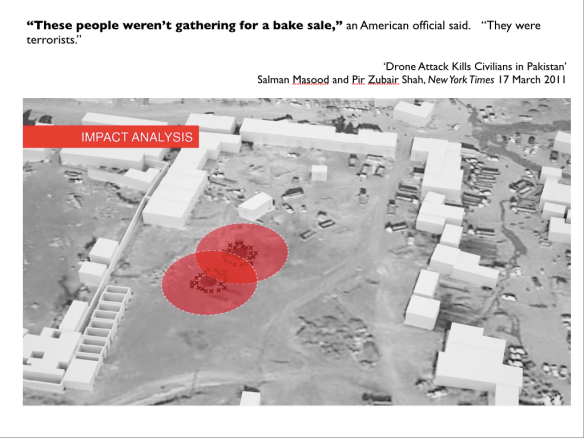

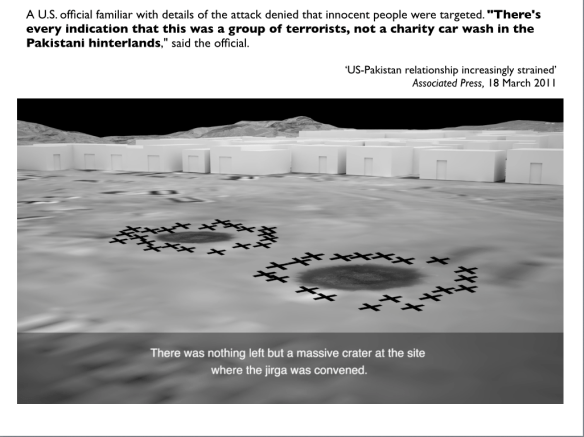

So I started to dig some more – WiFi on the train – and discovered that Eyal Weizman and his brilliant colleagues at Goldsmith’s Forensic Architecture had reconstructed this very strike (the image above is from their work):

‘In the absence of on-the-ground photographic or video documentation, and with no visible impact on buildings, this investigation unfolded by cross-referencing witness testimonies with satellite imagery. An examination of before and after satellite imagery indicated two areas with surface disturbance consistent with the reported missile strikes, thus allowing us to confirm the location of the strike. From the testimonies of survivors and eye-witnesses, we harvested spatial information that helped us to generate a 3D model of the site of the drone strike on the Jirga.’

Then all (!) I had to do was go back in to my e-files (each morning I work my way through the press, copying and pasting reports and commentaries into a series of files so that I have my own searchable archive), recover the glosses provided by that anonymous official, and put them together with the reconstruction. Here’s the result:

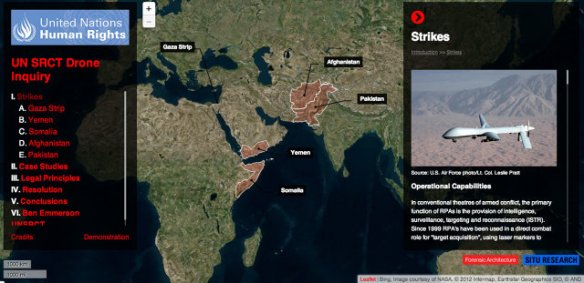

You can read more about these reconstructions here (‘The forensics of a lethal drone attack’). This strike is one of several investigated by the UN’s Special Rapporteur Ben Emmerson, and you can find much more information at the interactive website produced in collaboration with Forensic Architecture and SITU Research that accompanies his written report to the United Nations (28 February 2014) (the Datta Khel incident is summarised in paragraph 50, but the website provides a far richer understanding). You can also download hi-res versions of Forensic Architecture’s stills and videos here.

What I find so significant is that the anonymous official provided a series of different and, as I’ve said, bizarre (even offensive) descriptions of what the assembly in Datta Khel was not: but he was clearly incapable of recognising what it was. This was certainly another performance of the space of exception, but it was plainly not a legal ‘black hole’, as some commentators gloss Agamben. The only ‘black holes’ were the craters in the ground and the conspicuous failure to recognise the operative presence of customary law.