Hard on the heels of yesterday’s post about Metadata+ – and my earlier, necessarily impressionistic discussion of the National Security Agency, drone strikes in Pakistan and what I called ‘the everyware war’ – comes a report from Jeremy Scahill and Glenn Greenwald at The Intercept that details the NSA’s role in the US’s targeted killing programme.

The programme is carried out by multiple means and multiple agencies (including the US military), but the main source for their report is a former drone operator from Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) – and readers of Jeremy’s Dirty Wars will know that it is JSOC rather than the CIA that is his main critical target. We’ve known about the NSA’s Geolocation Cell (‘GeoCell’) for some time now. Last summer Dana Priest outlined the history of collaboration between the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency and the NSA, which she traced back to the months following 9/11, and the determination to use cell phones as ‘targeting beacons’:

The cell opened up chat rooms with military and CIA officers in Afghanistan — and, eventually, Iraq — who were directing operations there. Together they aimed the NSA’s many sensors toward individual targets while tactical units aimed their weaponry against them.

A motto quickly caught on at Geo Cell: “We Track ’Em, You Whack ’Em.”

But, as Scahill and Greenwald show, the process remains far from reliable. Their informant confirms that strikes are often carried out on the basis of metadata analysis and cellphone tracking (‘SIGINT’) rather than human intelligence (agents on the ground), and he admits that it is a hit or miss affair, and literally so: ‘high value targets’ have been killed, but so too have innocent people.

[T]he geolocation cells at the NSA that run the tracking program – known as Geo Cell – sometimes facilitate strikes without knowing whether the individual in possession of a tracked cell phone or SIM card is in fact the intended target of the strike.

“Once the bomb lands or a night raid happens, you know that phone is there,” he says. “But we don’t know who’s behind it, who’s holding it. It’s of course assumed that the phone belongs to a human being who is nefarious and considered an ‘unlawful enemy combatant.’ This is where it gets very shady.”

There are several lists of so-called High Value Targets, but the operational problem is, as he concedes, ‘We’re not going after people – we’re going after their phones.’

[T]racking people by metadata and then killing them by SIM card is inherently flawed. The NSA “will develop a pattern,” he says, “where they understand that this is what this person’s voice sounds like, this is who his friends are, this is who his commander is, this is who his subordinates are. And they put them into a matrix. But it’s not always correct. There’s a lot of human error in that.”

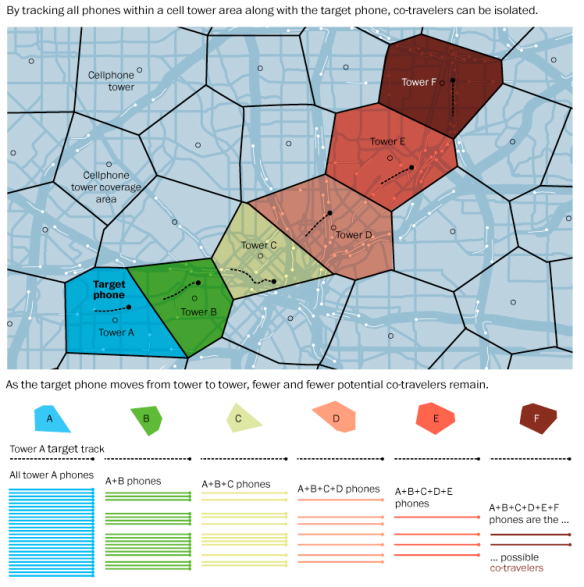

The programme relies on more than what we have come to think of as standard (though still shocking) NSA intercepts of communications. For more on the NSA’s global tracking of cellphones, see Barton Gellman and Ashkan Soltani here, from which I’ve taken the image below.

As the graphic shows, the standard method of ‘co-location analytics’ tracks not only targets but also their associates (‘co-travellers’) using cell towers (which have in turn become key targets for insurgent attack in Afghanistan partly for this reason).

For clandestine operations in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere the NSA’s geolocation system codenamed ‘GILGAMESH’ (king of the city-state of Uruk in Mesopotamia: where do they get these names from?) equips Predators assigned to JSOC with ‘virtual base-tower transceivers’ that can track and locate a SIM card to within 30 feet; the information is then used in near-real time to activate an air strike or a night raid through a network that has ‘cued and compressed numerous kill chains’.

The CIA uses another system, codenamed SHENANIGANS (no mystery about that one), which collects data ‘from any wireless routers, computers, smart phones or other electronic devices that are within range.’ Last fall Greg Miller, Julie Tate and Barton Gellman described how the system was used in the targeted killing of Hassan Ghul in Mir Ali in Waziristan in October 2012:

In the search for targets, the NSA has draped a surveillance blanket over dozens of square miles of northwest Pakistan. In Ghul’s case, the agency deployed an arsenal of cyber-espionage tools, secretly seizing control of laptops, siphoning audio files and other messages, and tracking radio transmissions to determine where Ghul might “bed down.”

The e-mail from Ghul’s wife “about her current living conditions” contained enough detail to confirm the coordinates of that household, according to a document summarizing the mission. “This information enabled a capture/kill operation against an individual believed to be Hassan Ghul on October 1,” it said.

The file is part of a collection of records in the Snowden trove that make clear that the drone campaign — often depicted as the CIA’s exclusive domain — relies heavily on the NSA’s ability to vacuum up enormous quantities of e-mail, phone calls and other fragments of signals intelligence, or SIGINT.

To handle the expanding workload, the NSA created a secret unit known as the Counter-Terrorism Mission Aligned Cell, or CT MAC, to concentrate the agency’s vast resources on hard-to-find terrorism targets. The unit spent a year tracking Ghul and his courier network, tunneling into an array of systems and devices, before he was killed. Without those penetrations, the document concluded, “this opportunity would not have been possible.”

The two systems are agency-specific but they often work in concert: Scahill and Greenwald note one joint operation in 2012, ‘VICTORYDANCE’, that ‘mapped the WiFi fingerprint of nearly every town in Yemen.’

The documents that they draw upon are from various dates, extending back to 2005, so that these are a series of snapshots of an uneven and developing set of systems. Still, the concerns about accuracy are persistent, and although they don’t cite her report Kate Clark‘s forensic examination of the attempted killing of the Taliban shadow governor of Takhar province in Afghanistan in September 2010 provides an exceptionally detailed account of the dangers of relying on metadata and cellphone tracking. Here is what I said about this in my discussion of Targeted Killing and Signature Strikes:

On 2 September 2010 ISAF announced that a ‘precision air strike’ earlier that morning had killed [Muhammad Amin] and ‘nine other militants’. The target had been under persistent surveillance from remote platforms – what Petraeus later called ‘days and days of the unblinking eye’ – until two strike aircraft repeatedly bombed the convoy in which he was travelling. Two attack helicopters were then ‘authorized to re-engage’ the survivors. The victim was not the designated target, however, but Zabet Amanullah, the election agent for a parliamentary candidate; nine other campaign workers died with him. Clark’s painstaking analysis clearly shows that one man had been mistaken for the other, which she attributed to an over-reliance on ‘technical data’ – on remote signatures. Special Forces had concentrated on tracking cell phone usage and constructing social networks. ‘We were not tracking the names,’ she was told, ‘we were targeting the telephones.’

The Takhar case has been on my mind again because, as Kate revealed in a new report last week, the agencies involved in targeted killing reach beyond the NSA – and beyond the USA.

The involvement of Britain’s GCHQ and other ‘Five Eyes’ sites in global surveillance has become well-known in recent months – and see Nikolas Kozloff for a short reflection on its ‘geopolitics of racism‘ (though he ignores the willingness to spy on other European states and allies) – but Kate’s new report is significant for what it reveals about the complicity of civilian police agencies. In August 2013 Habib Rahman, who lost two brothers, two uncles and his father-in-law in the Takhar attack, petitioned for a judicial review of the involvement of Britain’s Ministry of Defence and the (civilian) Serious Organised Crime Agency (SOCA) – whose brief includes the drug trade from Afghanistan – in the compilation of the Joint Prioritised Effects List (one of the lists of priority targets used by the Pentagon).

SOCA is part of the Joint Inter-Agency Afghanistan Task Force (JIATF), a military-police task force based at Kandahar AFB that also includes the US Drug Enforcement Agency, the US military and the British military. In a US Senate report on the nexus between drug trafficking and insurgency, ‘Afghanistan’s Narco War‘, a SOCA investigator described the proposed collaboration as ‘a critical opportunity to blend military and law enforcement expertise’ (p.15). At the time (August 2009) the JIATF was awaiting formal approval from Washington and London, but informal collaboration was already under way, and the SOCA officer was enthusiastic about its consolidation:

‘In the past, the military would have hit and evidence would not have been collected,’ he explained. ‘Now, with law enforcement present, we are seizing the ledgers and other information to develop an intelligence profile of the networks and the drug kingpins.’ An American military officer with the project was blunter, telling the committee staff, ‘Our long-term approach is to identify the regional drug figures and corrupt government officials and persuade them to choose legitimacy or remove them from the battlefield.’

Rahman’s lawyers argued:

As a civilian policing organisation SOCA has no legitimate or lawful role to play in the compilation or administration of this Kill List – it has no authority to be involved in military operations and the killing of individuals. The courts must urgently review whether the SOCA’s and indeed the UK’s role in the compilation, review and execution of this list if unlawful. Incidents like that affecting our client must be properly investigated.

In response, SOCA acknowledged making its intelligence available to the military, but added these provisos:

SOCA places restrictions on the dissemination of intelligence to the ISAF. Intelligence which is disseminated by SOCA is required to include handling conditions which require the express approval of the originator if it is proposed to use the material for military targeting purposes. If the mission is to arrest, with a view to criminal investigation and potential prosecution, SOCA would ordinarily be prepared to provide and/or allow the use of its intelligence. On the other hand, if the primary option for a mission is to use lethal force, SOCA would not provide intelligence or allow the use of its intelligence in support of such a mission, save potentially where the individual who is the target of the operation poses a significant and immediate threat to he lives of others (and so such disclosure would be for the purpose of preventing a criminal offence).

The judge dismissed Rahman’s claim. But read that last sentence again. These missions are almost always designated as ‘kill or capture’, and while in practice ‘kill’ is often preferred over ‘capture’, how likely is it that the ‘primary option for a mission’ would be advertised as a targeted killing before the intelligence were made available? An undated US Justice Department memo setting out conditions for targeted killing included the stipulation that where ‘capture is infeasible’ the US would continue ‘to monitor whether capture becomes feasible’, which turns the mission (and SOCA’s proviso) into a moving target in more ways than one. Once intelligence has been incorporated into the matrix it can hardly be withdrawn or embargoed.

The judge dismissed Rahman’s claim. But read that last sentence again. These missions are almost always designated as ‘kill or capture’, and while in practice ‘kill’ is often preferred over ‘capture’, how likely is it that the ‘primary option for a mission’ would be advertised as a targeted killing before the intelligence were made available? An undated US Justice Department memo setting out conditions for targeted killing included the stipulation that where ‘capture is infeasible’ the US would continue ‘to monitor whether capture becomes feasible’, which turns the mission (and SOCA’s proviso) into a moving target in more ways than one. Once intelligence has been incorporated into the matrix it can hardly be withdrawn or embargoed.

And that final clause about pre-emptive action opens up a discretionary space that the Obama administration has already sought to enlarge with its demands for an ‘elongated’ concept of imminence in which the ‘immediacy’ of the threat is subject to prolongation to the point of contortion.

Rahman is not the first victim to have been rebuffed by British courts. Last month the Court of Appeal

dismissed Noor Khan‘s case against the British Government over the role of GCHQ in providing ‘locational intelligence’ for a CIA-directed drone strike in March 2010 in Miranshah in North Waziristan that killed his father. The ruling accepted that the case put forward by Noor Khan’s barrister – that the provision of such intelligence risked contravening the Serious Crimes Act (2007) – was ‘attractive’ and ‘persuasive’, but concluded that the review could not proceed because the claims

‘involve serious criticisms of the acts of a foreign state. It is only in certain established circumstances that our courts will exceptionally sit in judgment of such acts. There are no such exceptional circumstances here.’

The state of exception, it turns out, is not so exceptional… To be continued.