This is the first of a series of posts as I work my way through Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone (2013), which has finally arrived on my desk. I’ve loosely summarised the project and its relation to Chamayou’s previous work before, and in these notes I’ll combine a summary of his argument with some extended readings and excerpts from his sources and some comments of my own. I hope readers will find these useful; they are an aide-memoire for me, and a way of working out some of my own ideas too, but do let me know if all this is helpful (especially for those with no French).

This is the first of a series of posts as I work my way through Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone (2013), which has finally arrived on my desk. I’ve loosely summarised the project and its relation to Chamayou’s previous work before, and in these notes I’ll combine a summary of his argument with some extended readings and excerpts from his sources and some comments of my own. I hope readers will find these useful; they are an aide-memoire for me, and a way of working out some of my own ideas too, but do let me know if all this is helpful (especially for those with no French).

I’m pleased to say that he draws on several of my essays about drone warfare, including ‘From a view to a kill’, ‘Lines of descent’, and even ‘The everywhere war’ (all available under the DOWNLOADS tab), so I won’t re-trace in any detail our (considerable) common ground.

The first section of Theory of the drone is devoted to Techniques and Tactics and, as I noted previously, it’s good to read a philosopher engaging with the materialities and corporealities of contemporary war in such close detail. I’ll start with the first two chapters, which read together provide some more lines of flight for today’s remote operations. I don’t call these ‘genealogies’ lightly: as you’ll see next time, there are definite and deliberate echoes of Foucault in the argument (though Chamayou is no disciple).

1: ‘Methodologies for hostile environments’

It’s become a truism to say that drones are ideally suited for ‘dirty, dangerous or difficult’ tasks, and Chamayou begins with an interesting article written by John W. Clark for the New Scientist in 1964 on ‘Remote control in hostile environments’.

Clark described the development of technologies ‘of manipulation at a distance – what he called ‘telechirics’ (a term that Chamayou appropriates for his own purposes, from the Greek tele meaning ‘distance’ and kheir meaning ‘hand’) – so that people no longer had to expose themselves to danger to earn a living: from the extremes of outer space, exposure to nuclear radiation and deep ocean exploration to more mundane, everyday projects like fire-fighting, tunnelling, or mining. The key advance was the use of ‘a vehicle operating in the hostile environment under remote control by a man in a safe environment’.

Clark emphasised the remoteness – ‘there is no direct connection between the operator and his machine’ – because in his view the system depended on the capacity of the human operator ‘to “identify himself” with his remotely-controlled machine, even though it may be completely non-anthropomorphic in appearance and configuration’. In effect, Clark wrote, ‘his consciousness is transferred to an invulnerable mechanical body’ which implies, in turn, that ‘systems of this type are no substitutes for human judgment’. (For this reason, while Clark believed that a ‘telechiric system’ could be provided with a variety of sensors, vision – ‘by far our most valuable sense’ – was typically provided through a single-channel, closed-circuit television system). Indeed, the capacity for judgment is enhanced by partitioning space, as Chamayou notes, placing the operator in a ‘safe zone’ outside the ‘danger zone’. The danger zone is a site of surveillance and intervention (‘by a cable or by a radio-link’), Chamayou underlines, but not a site of habitation.

It’s not difficult to see how these propositions can be carried over to the use of combat drones. Interestingly, Clark had been employed by the Hughes Aircraft Company where he originally developed his ideas on ‘remote handing’ (what he then called mobotry). He had noted that ‘the electronic techniques which have been developed in recent years, primarily in connection with guided missiles and radar, are finding increasing application in connection with remotely controlled systems for accomplishing physical operations within areas which are uninhabitable due to the presence of a hostile environment’, and in the closing section of the research paper he noted that ‘a remotely-controlled street-sweeper employing television for guiding and steering and a simple frequency coded command system has recently completed successful tests.’

Where? The Air Force Special Weapons Center in Albuquerque, which was dedicated to R& D of atomic and other ‘unconventional’ weapns (which was presumably not especially interested in keeping the streets clean). And at the end of the 1980s Clark’s old employer, Hughes Aircraft, would buy a fledgling drone manufacturing company, Leading Systems, from Abe Karem (‘the dronefather‘), and then promptly sell it on to General Atomics which, with Karem’s assistance, became the company responsible for the Predator.

These details are not included in Chamayou’s discussion – and I don’t mean this as a criticism: I admire both the brevity and the clarity of his account – and in fact no links to the military appeared in the New Scientist article. But Chamayou has found a subsequent, anonymous and remarkably telling comment on the article. Among the scenarios canvassed by Clark, this contributor wrote, one was conspicuous by its absence:

‘The minds of telechiricists are grappling with the problems of employing remotely-controlled machines to do the peaceful work of man amid the hazards of heat, radiation, space and the ocean floor. Have they got their priorities right? Should not their first efforts towards human safety be aimed at mankind’s most hazardous employment – the industry of war?… Why should twentieth-century men continue to be stormed at by shot and shell when a telechiric Tommy Atkins could take his place? ‘All conventional wars might eventually be conducted telechirically, armies of military robots battling it out be remote control, victory and defeat being calculated and apportioned by neutral computers, while humans sit safely at home watching on TV the lubricating oil staining the sand in sensible simile of their own blood.’

Sand? Chamayou doesn’t mention it [‘sand’ in his French translation becomes ‘dust’], but in fact the anonymous author opened his commentary by noting that the publication of Clark’s original article ‘coincided with the flare-up in the Yemen…’ The ‘flare-up’ was part of a civil war in Yemen, in which royalists (supported by Saudi Arabia) were pitted against republicans (supported by Egypt) and Britain was engaged in a series of irregular, covert operations that were repeatedly denied in Parliament.

And so it’s no accident, I think, that the anonymous contributor goes on to emphasize the importance of telechirics for asymmetric warfare:

‘Far-flung imperial conquests which were ours because we had the Maxim gun and they had the knobkerrie will be recalled by new bloodless triumphs coming our way because we have telechiric yeomanry and they, poor fuzzy-wuzzies, have only napalm and nerve-gas.’

By this means, Chamayou concludes, asymmetric warfare becomes unilateral: people still die, to be sure, but on one side only. And, as those hideous remarks I’ve just quoted make plain, the divide is profoundly racialized.

2: Genealogy of the Predator

My own inclination would be to make that plural – genealogies – and to identify multiple lines of descent, some of which (I think plausibly) can be traced back to the early twentieth century.

But Chamayou excludes many of them, including ‘target drones’ and – more directly relevant – various ‘aerial torpedoes’, which he sees as forerunners of the cruise missile (which can only be launched once) rather than the combat drone (which can be used many times over). This distinction is useful, but it’s complicated by Project Aphrodite’s experiments with explosive-filled US bombers in the dog days of the Second World War, whose use of remote control and visual links – they’ve sometimes been called ‘video bombers’ – anticipates key elements of today’s remote operations (see also here, here, here and here).

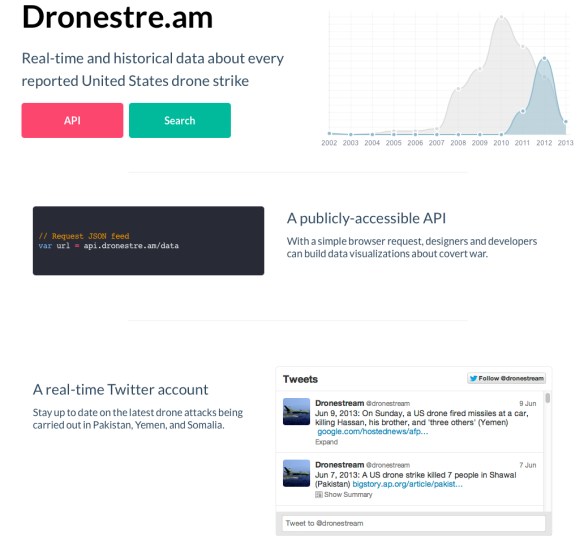

Chamayou does notice the American use of drones for aerial surveillance over North Vietnam – though he makes nothing of other elements, including the development of ‘pattern of life’ analysis and the installation of the sensor-shooter systems of the ‘electronic battlefield’ along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, both of which (as I argued in ‘Lines of descent’) were key elements in the much later development of unmanned aerial systems.

But these developments came to nothing, Chamayou contends, and in the 1970s the development of military drones was virtually abandoned by the US: it was Israel that showed the way to the future.

During the Yom Kippur War of 1973 the Israelis used ‘decoy drones’ to draw the fire of missile batteries and then sent in conventional strike aircraft before the Egyptians could re-load: Chamayou doesn’t note it, but those drones were designed and built in under a month by Abe Karem and his team. In 1982 the IDF repeated the tactic against Syrian batteries defending Palestinian strongholds in the Bekaa Valley.

But Israel literally showed the US the way to the future in another, much more remarkable incident in 1983. Here is the original account (by Jim Schechter) on which Chamayou draws from Popular Science in October 1987:

But Israel literally showed the US the way to the future in another, much more remarkable incident in 1983. Here is the original account (by Jim Schechter) on which Chamayou draws from Popular Science in October 1987:

‘Two days after a terrorist bomb destroyed the [US] Marine barracks in Beirut in October 1983, Marine Commandant Gen. P. X. Kelley secretly flew to the scene. No word of his arrival was leaked. Hours later in Tel Aviv the Israelis played back the tape for the shocked Marine general. The scene, they explained, was transmitted by a Mastiff RPV circling out of sight above the barracks.’

Peter Hellman in ‘The little airplane that could’ (in Discover, February 1987) fills in some of the details. Kelley ‘had been photographed during his outdoor movements in Beirut — his head targeted in cross hairs‘ (my emphasis). He explains:

‘Unobserved by the Marines, a miniaturized Israeli RPV (remotely piloted vehicle) called Mastiff had circled 5,000 feet overhead during Kelley’s visit. Despite its twelve-foot wing span (just a shade longer than a California condor’s), at that altitude the Mastiff couldn’t be seen by the naked eye. And with its fiber-glass body, it was almost impossible to detect by radar. Nor could the putt-putt of its two-cylinder 22-horsepower engine be heard. But a zoom-lensed video camera peering down from a clear plastic bubble in its belly had a splendid view of the touring general. On a signal from controllers more than 50 miles away, the mini-RPV left as furtively as it had come, and flew into a net set up outside its mobile ground station.

As Schechter laconically put it, the Americans got the message, and in the 1980s their interest in developing remotely piloted aircraft for ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) dramatically increased.

There are all sorts of other connections between the US and Israel when it comes to both the development of UAVs and their later use for targeted killing. What Chamayou is most interested in is precisely the development of UAVs as hunter-killers, which (as I’ll explain in my next post in the series) he links to the transformation of warfare into man-hunting. And, as I’ll try to show, that’s when things start to get extremely interesting…