The more I think about corpography (see also ‘Corpographies under the DOWNLOADS tab) – especially as part of my project on casualty evacuation from war zones – the more I wonder about Grégoire Chamayou‘s otherwise artful claim that with the advent of armed drones the ‘body becomes the battlefield’. He means something very particular by this, of course, as I’ve explained before (see also here).

But let me describe the journey I’ve been taking in the last week or so that has prompted this post. Later this month I’m speaking on ‘Wounds of war, 1914-2014‘, where I plan to sketch a series of comparisons between casualty evacuation on the Western Front (1914-18) and casualty evacuation from Afghanistan. I’ve already put in a lot of work on the first of these, which will appear on these pages in the weeks and months ahead, but it was time to find out more about the second.

En route I belatedly discovered the truly brilliant work of David Cotterrell who is, among many other things, an installation artist and Professor of Fine Art at Sheffield Hallam University. He became interested in documenting the British military casualty evacuation chain from Afghanistan, and in 2007 secured access to the Joint Medical Forces’ operations at Camp Bastion in Helmand. He underwent basic training, a course in even more basic battlefield first-aid, and then found himself on an RAF transport plane to Bastion. The Role 3 Hospital was, as he notes, a staging-ground. ‘Field hospitals are islands between contrasting environments,’ he wrote in his diary, ‘between the danger and dirt of the Forward Operating Bases and the order and convention of civilian healthcare.’ You can read a long, illustrated extract from the diary (3 – 26 November 2007) here, follow the photo-essay as a slideshow here, and explore David’s many other projects on his own website here.

The diary is immensely interesting and informative in its own right, not least about the exceptional personal and professional difficulties involved in documenting the evacuation process. Here there’s a helpful comparison to be made with journalist Ann Jones‘s no less brilliant They were soldiers: how the wounded return from America’s wars (more on this in a later post), which starts at the US military’s own Level III Trauma Center, the Craig Joint Theater Hospital at Bagram, and moves via Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, the largest US hospital outside the United States, to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington DC.

The diary is immensely interesting and informative in its own right, not least about the exceptional personal and professional difficulties involved in documenting the evacuation process. Here there’s a helpful comparison to be made with journalist Ann Jones‘s no less brilliant They were soldiers: how the wounded return from America’s wars (more on this in a later post), which starts at the US military’s own Level III Trauma Center, the Craig Joint Theater Hospital at Bagram, and moves via Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, the largest US hospital outside the United States, to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington DC.

David’s visual record is even more compelling, as you would expect from a visual artist, not only in its documentary dimension but also in the installations that have been derived from it. In Serial Loop, for example, we are confronted with a looped film showing the endless arrival of casualties at Bastion: ‘The sound of a continuously arriving and departing Chinook helicopter accompanies images of a bleak and wasted landscape; the banality of the film’s fixed perspective masks the dramas that unfold within the ambulances as they travel to triage.’

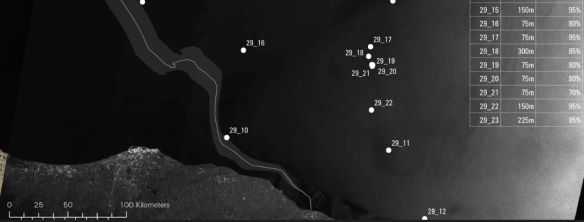

9-liner explores what David calls ‘the abstraction of experience within conflict’:

9-Liner explores the dislocation between the parallel experiences of casualties within theatre. It is a quiet study of a dramatic event: the attempt to bring an injured soldier to the tented entrance of the desert field hospital. The screens show apparently unrelated information. JCHAT – a silent scrolling codified message – runs on a central screen. Our interpretation of it is enabled through its relationship between one of two radically different but equally accurate views of the same event. To the left we see the Watchkeeper – a soldier manning phones and reading computer screens in a crowded office. On the right we view the MERT flight – the journey of the Medical Emergency Response Team in a Chinook helicopter.

SHU’s REF submission includes this summary of David’s work (one of the very few useful things to come out of that otherwise absurdist exercise):

The research made clear that soldiers recovering from life-changing injuries had limited means of reconstructing the narrative of their transformative experiences. From the time of wounding through to secondary operations in the UK, many soldiers remained sedated or unconscious for a period of up to five days. The radical physical transformation that had occurred during this period was not adequately reconciled through medical notes, and the embargo on photographic documentation of incident and subsequent medical procedures served further to obscure this period of lost memory.

A culture of secrecy meant that medical professionals were unable to access documentation of the expanded care pathway with which they, and their colleagues, were engaged. This fragmentation of experience and understanding within the process of evacuation, treatment and rehabilitation meant that the assessment of the contradictions and disorientation experienced by casualties and medical practitioners was denied to front-line staff.

Family members, colleagues and members of the public outside the immediate environment of the military were unable to visualise or understand the transformative effects of conflict on directly affected civilians and soldiers. Partly as a result, the scope for public debate to engage meaningfully with the longer term societal cost of contemporary conflict was limited.

The submission goes on to list an impressive series of debriefings, presentations to military and medical professionals, major exhibitions, and follow-through research in Birmingham.

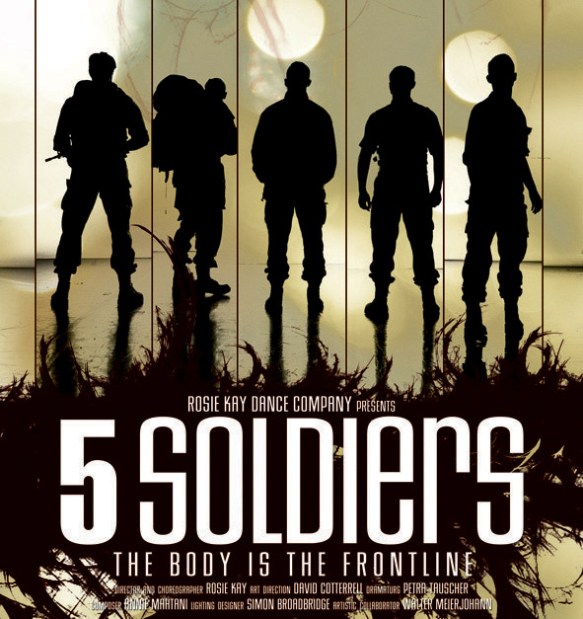

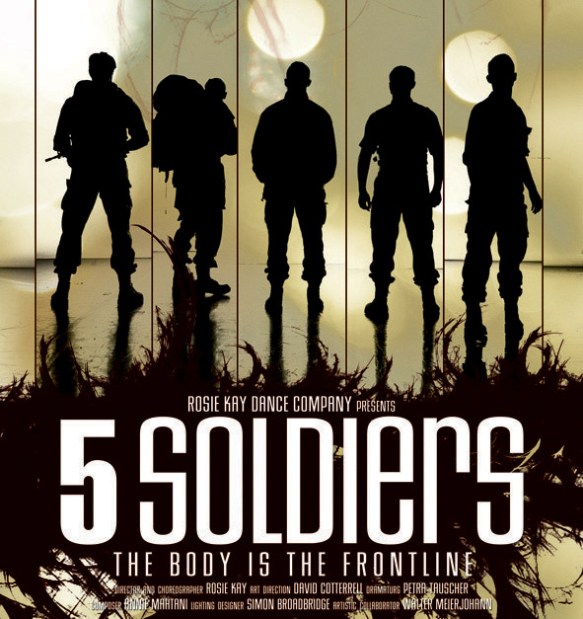

And it’s one of those follow-throughs that prompted me to think some more about corpographies. I’d noted the connection between corpography and choreography in my original post, but David’s extraordinary collaboration with choreographer Rosie Kay and her dance company gives that a much sharper edge. Again, there’s a comparison to be drawn – this time with Owen Sheers‘s impressively researched and executed body of work, not only the astonishing Pink Mist but also The Two Worlds of Charlie F (2012), which was a stage play based on the experiences of wounded soldiers who also made up the majority of the cast (see my discussion of these two projects here).

5 Soldiers started life as a stage presentation in 2010 (watch some extracts here):

A dance theatre work with 5 dancers, it looks at how the human body is essential to, and used in, warfare. 5 SOLDIERS explores the physical training that prepares you for war, as well as the possible effects on the body, and the injury caused by warfare.

Featuring Kay’s trademark intense physicality and athleticism, 5 SOLDIERS weaves a journey of physical transformation, helping us understand how soldiers are made and how war affects them.

5 SOLDIERS is a unique collaboration between award-winning choreographer Rosie Kay, visual artist David Cotterrell and theatre director Walter Meierjohann. It follows an intense period of research, where Rosie learnt battle training with The 4th Battalion The Rifles and David spent time in Helmand Province with the Joint Forces Medical Group.

Rosie explained her commitment to the project (and her training with The Rifles) like this:

“I wanted to look at how the physicality of a soldier’s job defines them –like a dancer, the soldier is drilled, trained, their responses becoming automatic, but can anything prepare you for the realities of war? It is young soldiers and their bodies that are the ultimate weapon in war – their strength and weaknesses may win or lose a battle, their ability to harm or injure others is key to victory. While war is surrounded with weaponry, uniforms, history and ceremony, the real business is human, dirty, messy, painful and happening right now.”

(She is, not coincidentally, an affiliate of the School of Anthropology at Oxford).

And now there’s a film version that works as a multi-screen installation (screen shot above).

Instead of just creating a short film, the team wanted the web user to get a truly interactive way to watch dance, and actually feel that they can go inside the minds and the body of the work. The 80-minute work was cut to just 10 minutes long, and the company spent one week filming in a huge aircraft hangar at Coventry Airport…

Using a variety of cutting edge filming techniques, the collaborative team have created a 13 angle edit that takes you into the heart of the work, follows each of the dancers, and zooms out so that the performers appear to be like ants in a huge empty landscape.

You can see the interactive, multi-perspectival version here. This relied on helmetcams, and there’s a fine, more general commentary on this in Kevin McSorley‘s ‘Helmetcams, militarized sensation and “somatic war”‘ here. But here’s the short, ‘director’s cut’ version:

And look at the tag-line: ‘The body is the frontline’. It’s not only drones that make it so.