I’m still working on revising “Deadly Embrace” (though needless to say I should be working on other things…). There were originally three main sections to the primary focus on waging war from a distance – information, logistics, weapons – but I need to add a fourth: intelligence. The discussion of ‘information’ is concerned with what publics know of war at a distance – with news and the mediatisation of war (and thus with censorship and propaganda too) – but I’ve now done sufficient work on targeting to realise that the whole question of intelligence – of what politicians and the military claim to know of the (distant) enemy – needs to be incorporated.

In each case I provide an historical sketch and a contemporary discussion. The historical sketches each begin at different times; starting-points are inevitably arbitrary, of course, but the sharper point is that historical transformations are usually uneven and jagged so I’ve identified a series of different moments to frame each of the main sections.

My original inspiration was Mary Favret’s War at a distance: Romanticism and the making of modern wartime, and for that reason I begin with ‘world wars’ that are outside the parameters of the supposedly canonical First and Second World War and I end with other ‘world wars’ (‘the everywhere war’) in our own present. Favret says this:

‘Enumerations of world wars … do not typically begin with the wars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century… Despite the fact that they comprehended armed conflict not only in Europe, but in Africa, Asia and the Americas; despite the fact that they worried waters from the Philippine Islands to the Indian Ocean, from the Cape of Good Hope to the Mediterranean, from the English Channel westward to Chesapeake Bay and Gulf of Mexico: nonetheless these wars are thought not to encompass the world. And yet, unlike the earlier Seven Years’ War, which could boast a comparable geographical reach, these wars from their revolutionary beginning were unequivocally addressed to the world.’

There is another dimension to this – even in this sketch you can glimpse a series of questions about the limits of combat zones that will, eventually, issue in a transition from ‘battlefields’ to diffuse, discontinuous battlespaces – but it’s that idea of wars being addressed to the world – and hence of an audience (a term which seems inadequate for what will become a viewing public) – that prompts my interest in ‘information’.

Favret identifies a dialectic between what she calls ‘eventfulness’ and ‘eventlessness’: in the late eighteenth century the regular arrival of news imparted a structuring rhythm to wartime, an episodic temporality of ‘punctuated eventfulness’, but she notes that thus this ‘created simultaneously a sense of living in the meantime’, waiting for news of events that had already happened but of which the public knew nothing because it took so long for letters and dispatches to arrive.

These are arresting suggestions, not least because Favret insists that this peculiarly modern notion of ‘wartime’ is not a twentieth-century artefact (for another, distinctively American view, with a different chronology, see Mary Dudziak’s War Time: an idea, its history, its consequences (2012)). Favret has no truck with Virginia Woolf’s identification of a gulf between the Napoleonic Wars and the Second World War. Writing in 1940, she had claimed that ‘wars were then remote, carried on by soldiers and sailors, not private people. The rumours of battle took a long time to reach England… Today we hear the gunfire in the Channel. We turn on the wireless; we hear an airman telling us how this very afternoon he shot down a raider… Scott never saw sailors drowning at Trafalgar; Jane Austen never heard the cannons roar at Waterloo.’ For that reason, Woolf thought, there was a silence in their writings. And yet Favret hears something in that silence: ‘Precisely in these registers of the mundane and the unspectacular, registers that have mistakenly been read as signs of immunity – or worse, obliviousness – British romantic writers struggled to apprehend the effects of foreign war.’

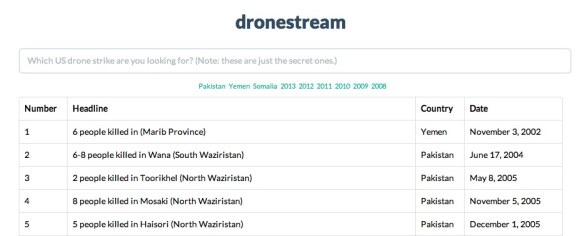

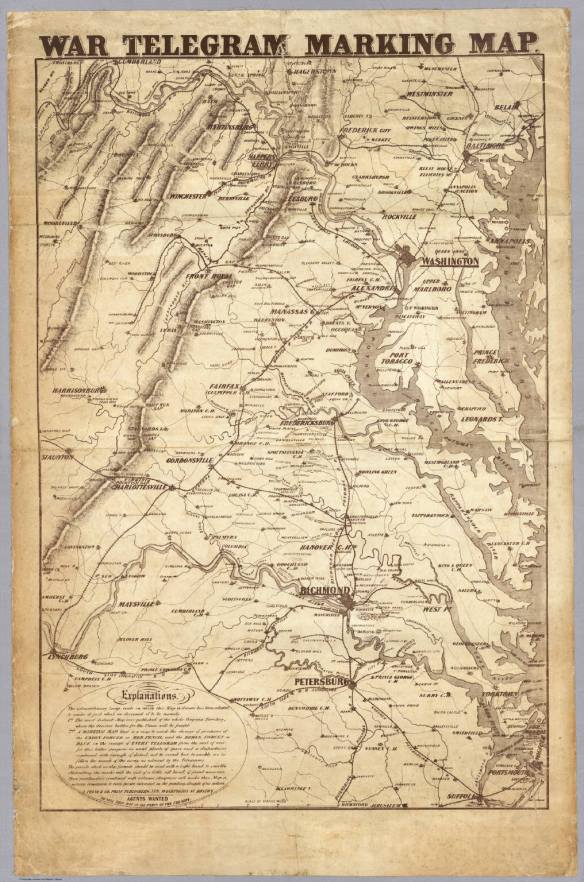

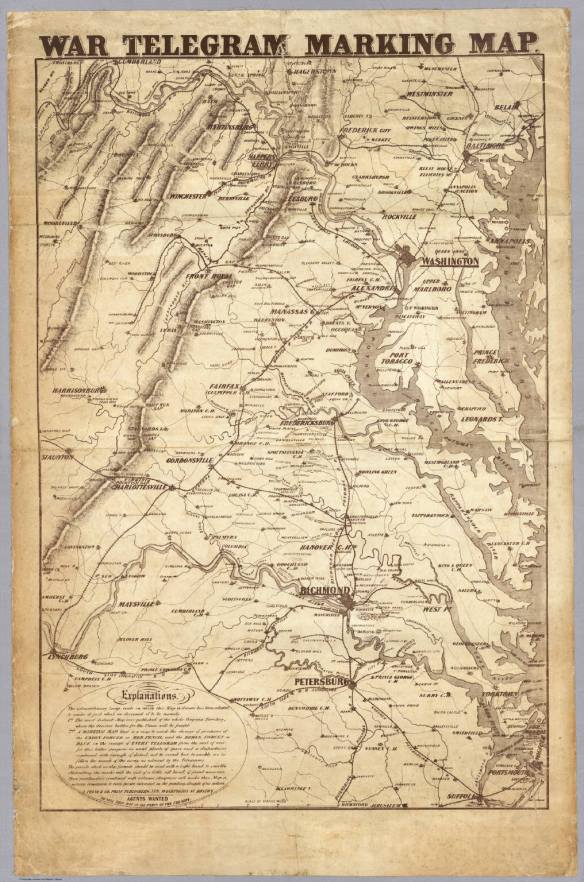

As this suggests, Favret’s interests direct her attention to the literary world – especially poetry – and in doing so she usefully reminds us that the emergence of the public sphere in eighteenth-century Britain involved more than spaces of rational articulation, which is why she constantly appeals to a landscape of affect. Yet the response to distant violence was increasingly also a matter of report, comment and debate, which allows more formal calibrations of ‘eventfulness’ through the press. Here, as in much else, I’m indebted to Allan Pred’s luminous work on the circulation of information, but I’m most interested in the emergence of a transnational public sphere that, after Morse’s successful demonstration of the telegraph in 1844, was increasingly an electric sphere: and one that transformed public awareness of ‘war at a distance’. So my discussion of information begins with the Crimean War (which saw the birth of the war correspondent) and the American Civil War (usually seen as ‘the first telegraph war’). In the latter, the telegraph played a vital role in communications, intelligence (by virtue of being tapped) and logistics, but I’m particularly interested in the sense of immediacy conveyed through wire reports. Louis Prang devised this map, sold through news-stands in Northern cities, so that readers could follow the progress of the war in more or less real time:

As Susan Schulten explains,

‘Prang was responding to the public’s desire not just for news, but the immediacy of “telegraphed” news. Unlike other battle maps which were issued after the fact, his was designed to follow the march in real time. He issued colored pencils — blue for Confederate forces, red for Union — to mark the advances, retreats and clashes that would be regularly reported by telegraph in any newspaper throughout the Union home front. Rather than waiting for maps to be issued after the battles, Prang enabled the viewer to track the invasion as it unfolded, with both victories but also terrible defeats and missed opportunities.’

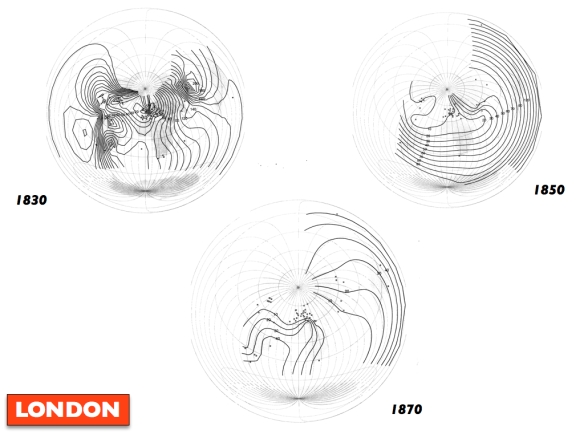

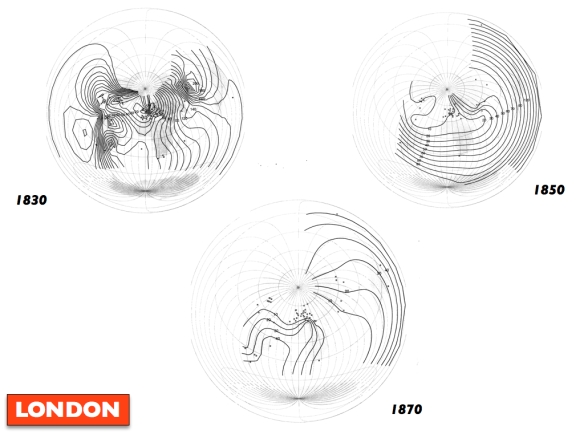

But for many audiences outside America, it was probably the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 that was the decisive episode in this new geography of immediacy. By then the uneven but none the less global geography of the telegraph had transformed the circulation of information; I’ve compiled this map of changing time-lags in the reporting of distant events in London newspapers in 1830, 1850 and 1870. It’s impressionistic at this resolution level, highly imperfect, and needs much more work, but it still conveys the scale (and selectivity) of time-space compression.

By 1870 public information circulated through multiple networks, and so its reception and interpretation was a hybrid affair: news of the war travelled out from a besieged Paris by balloon, and was transmitted by telegraph and conveyed by steamships carrying detailed newspaper reports to audiences around the world that were in thrall at the dramatic and unexpected turn(s) of events. In India, Australia and elsewhere editors and their readers were expected to be able to juggle multiple temporalities – the terse news from the telegraph and the fuller reports from the European newspapers that arrived simultaneously. Here is the Times of India on 3 October 1870:

‘The mass of detailed news of the war brought us by the mail … presents almost illimitable scope for reflection or retrospect, and for comparison with our previous impressions gathered from telegrams. But as the Indo-European [telegraph] line has come to the rescue with two or three days’ tolerably full news, we are recalled to the topics of the day and must, perforce, dwell on the considerations which are keeping all India, like the rest of the world, in suspense from hour to hour. The overland papers, in addition to the thrilling stories of the field, supply the more prosaic facts and permanent data by which each of our readers for himself will endeavour to support or modify the terse statements comprised in the telegraphic despatches.’

There was also a geography of truth involved: newspapers in Australia often preferred news that arrived via the ‘all-red line’ through Suez and India rather than via the United States or Panama (which was assumed to be pro-Prussian). Allowing for all these complexities, though, it’s the immediacy that is reiterated time and time again. The Sydney Morning Herald of 26 September 1870 declared that:

‘The rapid progress of events … is one of the most striking phases of modern warfare. The long delays of former times do not now task the patience of the world. The change of scene still reveals the rapid action of the stage. Towards the 8th of July the world becomes aware of a quarrel. By the 16th war is declared. In sixteen days more an immense slaughter on both sides reveals the dreadful nature of the conflict. By the 5th of September Napoleon surrenders himself as a prisoner of war, a Republic is proclaimed and every power of the state is centred in a provisional Government.’

And newspapers were now positioned to convey and capitalize on this immediacy: unlike the ‘freshest advices’ peddled in the eighteenth century, which were often remarkably stale, newspapers could now actualize the ‘newness’ of the news. So one week week later the Herald trumpeted: ‘We had never realised more completely the value of the telegraph than since the opening of this disastrous war.’

The relationship between distant publics and military violence was never a simple one, and the process that I’m cartooning here had its reversals. In the First World War, for example, the first British reporters to arrive on the Western Front were arrested and returned to England, and when just five journalists were eventually allowed access, there were strict limits on what they could report and their copy was heavily censored. Much that happened was hidden from view – then as now – and the Daily Mail’s William Beach Thomas wrote about his own distance from the horrors of the Somme thus:

‘I spoke with the men who had endured this the day after writing of the battle as it was unveiled to me, and felt that I had committed high treason. So easy is it to make the foul appear fair, to be tricked by the enchantment of distance…

‘All who have written about war … see it as the airman sees it in a large spaciousness where details are hid and only issues count. But let us remember the real war behind.’

You can see what he means – literally so – but perhaps there is also a sense in which immediacy blinds us to what is hidden from view. In the eighteenth century the ‘meantime’ between one report and another sustained a brooding anxiety about what might have happened, what was not yet known, and invited speculation and commentary, whereas the pell-mell escalation of events, of ‘one damn thing after another’, may work to close those spaces. I need to think more about this…

The story of reporting war at a distance continues with the addition of sound and moving image to text, sketch and photograph – including, during the Second World War, the radio broadcasts of bombing raids over Germany, cinema newsreels (in Britain the BBC went off the air from 1939 to 1946), and propaganda films – that all worked to reinforce the immediacy of those early telegraphic dispatches.

Reporter Wynford Vaughan Thomas and sound engineer Reg Pidsley in front of a Lancaster bomber, September 1943; the pair flew on an RAF raid to Berlin on the night of 3 September 1943, and their report was broadcast ‘live’ on BBC Radio two days later.

But this audio-visual immediacy also installed a peculiar intimacy. In his remarkable autobiography, The world of yesterday, which he started in 1934 and completed just before his suicide in 1942, Stefan Zweig captured what I’m trying to get at:

My father, my grandfather, what did they see? Each of them lived his life in uniformity. A single life from beginning to end, without ascent, without decline, without disturbance or danger, a life of slight anxieties, hardly noticeable transitions. In even rhythm, leisurely and quietly, the wave of time bore them from the cradle to the grave. They lived in the same country, in the same city, and nearly always in the same house. What took place out in the world only occurred in the newspapers and never knocked at their door. In their time some war happened somewhere but, measured by the dimensions of today, it was only a little war. It took place far beyond the border, one did not hear the cannon, and after six months it died down, forgotten, a dry page of history, and the old accustomed life began anew.

But now, he continued:

There was no escape for our generation, no standing aside as in times past. Thanks to our new organization of simultaneity we were constantly drawn into our time. When bombs laid waste the houses of Shanghai, we knew of it in our rooms in Europe before the wounded were carried out of their homes. What occurred thousands of miles over the sea leaped bodily before our eyes in pictures. There was no protection, no security against being constantly made aware of things and being drawn into them.

This too was a partial and partisan process, of course: British reporting of the Blitz was highly selective and subject to censorship, but the prevailing line was that Luftwaffe raids were indiscriminate acts of terrorism whereas Bomber Command’s strikes were precision strikes against military and industrial targets (some things evidently never change). Even so, this conditional intimacy was, perhaps, the culmination of the process glimpsed by Favret’s Cowper at his Georgian fireside: an unsettling sense of distant wars entering the home.

I say ‘culmination’ because, by the time of Vietnam, ‘the first television war’, even ‘the living-room war’, there are grounds for believing that many publics were becoming weary of the interpellations demanded by the incendiary images of distant death and destruction. That was, in part, what prompted Martha Rosler‘s brilliant photo-montage, Bringing the war home (1967-1972), that re-staged the Vietnam war in American domestic interiors (a project she reactivated in 2004 for the Iraq war). But this sense of familiarity, of the domestication of military violence, is also subject to reversal. Susan Sontag famously claimed that ‘Being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country is a quintessential modern experience’, and there has been a lively discussion of what Lilie Chouliaraki calls ‘the spectatorship of suffering’ and, in particular, of the publics produced through these modes of spectatorship. I still have much to read here – David Campbell’s measured critique of the ‘compassion fatigue’ thesis still haunts me – but I think it facile to say that we have become inured to military violence. James der Derian is surely right to identify the rise of a military-industrial-media-entertainment complex, but this hasn’t reduced war to entertainment tout court.

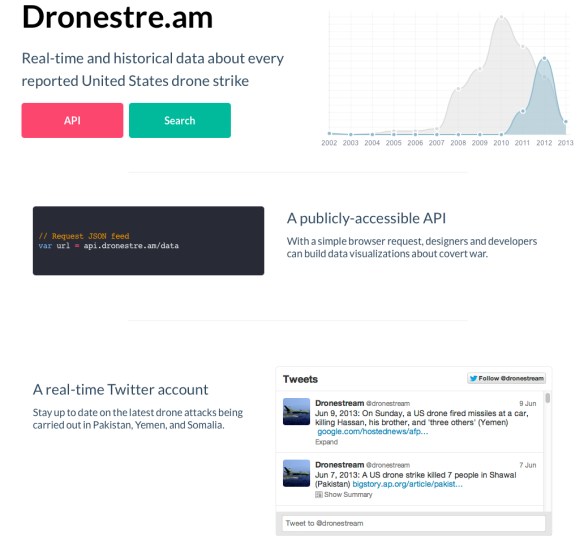

Advanced militaries have become increasingly adept at new modes of information warfare, using social media like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter to frame their actions and incorporating the flow of information into the very conduct of war, but this hasn’t enabled them to escape public scrutiny.

And so, the question: when we see the raw images of military (and paramilitary) violence around the world on YouTube, uploaded from multiple sources by activists and citizen-journalists, are we overwhelmed by what Favret would call the ‘eventfulness’ of it all? Or are we, as Zweig suggested, still ‘constantly drawn into our time’ (which is now, perhaps more than ever before, also the space of others)?

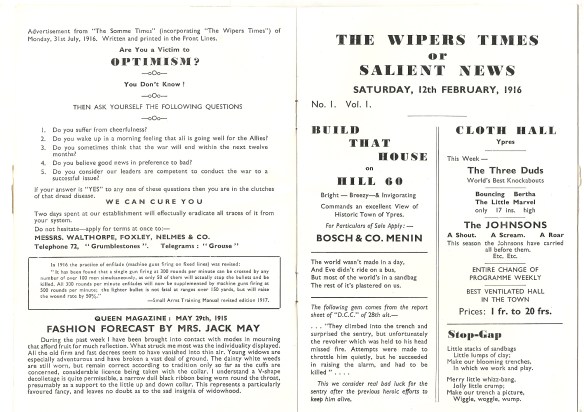

Back in the trenches again, revising “Gabriel’s Map”, and I see that the former President of the Royal Geographical Society – rather better known as Michael Palin (“This President is no more! He has ceased to be…. This is an EX-PRESIDENT!!”) – appears in a new BBC2 drama [also starring Ben Chaplin and Emilia Fox, left] based on the story of The Wipers Times, a trench newspaper written and printed on the Western Front during the First World War.

Back in the trenches again, revising “Gabriel’s Map”, and I see that the former President of the Royal Geographical Society – rather better known as Michael Palin (“This President is no more! He has ceased to be…. This is an EX-PRESIDENT!!”) – appears in a new BBC2 drama [also starring Ben Chaplin and Emilia Fox, left] based on the story of The Wipers Times, a trench newspaper written and printed on the Western Front during the First World War.