This is the first of a series of posts – continuing my discussions of Cities under Siege in Syria here, here and here – that will examine the siege of East Ghouta in detail.

This is the first of a series of posts – continuing my discussions of Cities under Siege in Syria here, here and here – that will examine the siege of East Ghouta in detail.

Today I begin with some basic parameters of East Ghouta, and in subsequent posts I’ll focus on three issues: the siege economy and geographies of precarity; military and paramilitary violence, ‘de-escalation’ and the endgame; and – the hinge linking these two and continuing my work on ‘the death of the clinic‘ – medical care under fire.

From paradise to hell on earth

Eastern Ghouta (‘Ghouta Orientale’ on the map from Le Monde above; ‘Damas’ is of course Damascus) has often been extolled as ‘a Garden of Eden’, ‘an earthly paradise’ and an ‘oasis’. In the fourteenth century Ibn al-Wardi described the Ghouta as ‘the fairest place on earth’:

. . . full of water, flowering trees, and passing birds, with exquisite flowers, wrapped in branches and paradise-like greenery. For eighteen miles, it is nothing but gardens and castles, surrounded by high mountains in every direction, and from these mountains flows water, which forms into several rivers inside the Ghouta.

Before the present wars much of the Ghouta was a rich, fertile agricultural landscape, a mix of small farms producing wheat and barley, fruits and vegetables (notably tomatoes, cucumbers and zucchini), and raising herds of dairy cattle whose milk and other products fed into the main Damascus markets. Most arable production depended on irrigation delivered through a de-centralised network of water pumps, pipes and channels.

The agrarian economy was seriously disrupted by the siege imposed by the Syrian Arab Army and its allies and proxies from 2012. The siege varied in intensity, but in its first report Siege Watch described the importance – and insufficiency – of these local resources:

While much of the population in Eastern Ghouta has become dependent on local farming for survival, the volume and variety of crops that are being produced is still insufficient for the population, since modern mechanized farming methods to water and harvest crops are unavailable and new seeds must be smuggled in. Some of the main crops being produced include wheat, barley, broad beans, and peas. The communities closest to Damascus are more urban areas with little arable land, so there is an uneven distribution of locally produced food within besieged Eastern Ghouta. Humanitarian conditions deteriorate in the winter when little locally produced food is available and prices increase.

Cutting off the electricity supply and limiting access to fuel also compromised vital irrigation systems (and much more besides), and many local people had to turn to wood for heating and cooking which resulted in extensive deforestation.

By November 2015 the price of firewood had soared:

Abu Ayman, an official in the Kafr Batna Relief Office, said that a family consisting of six people usually requires about 5 kg of firewood per day, costing up to 15,000 Syrian pounds (around $50) a month.Fruitless trees are our first source of firewood, as well as the destroyed houses in the cities of Jobar, Ain Tarma and Harasta,” says Asaad, a firewood seller in the town of Jisreen…Abu Shadi, the Director of Agricultural Office, said: “The orchards of Ghouta, known historically for their intense beauty, are on their way to desertification. Another year of the siege is enough to do so, especially since the urgent need for fuel prompted some people to cut down these trees without the knowledge of their owners.”

The military and paramilitary campaigns, the threats from mortars, snipers and bombs to workers in the fields, combined with a worsening drought (which made those irrigation pumps all the more important) to reduce agricultural production. And as the regime’s forces advanced so the agricultural base available to the besieged population contracted. (The reverse was also true: the regime desperately needed to regain access to its old ‘breadbaskets’, most of which were in rebel areas outside its control).

Much of the destruction of food resources was deliberate. This from Dan Wilkofsky and Ammar Hamou in June 2016, shortly after the Syrian Arab Army captured wheat fields in the south of the region:

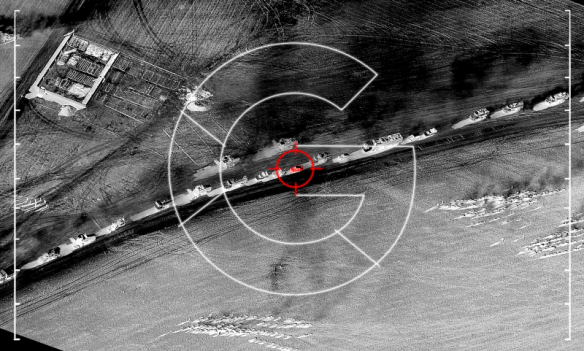

Residents of East Ghouta, where a half-million people have been encircled by the Syrian military and its allies, say the government is targeting their food supply as much as it is trying to gain ground. They say that weeks after capturing the area’s breadbasket, a stretch of farmland hundreds of acres wide, the government is using airstrikes and mortar attacks to start fires in the fields that remain in rebel hands [see photograph below].

“People gather the wheat and heap it up, only for the regime to target the piles and burn them,” Khalid Abu Suleiman… said on Thursday from the al-Marj region.

Fires have spread quickly through wheat fields sitting under the June sun. “When wheat turns yellow, the regime can spot it easily and a small shell is enough to burn the harvest,” Douma resident Mohammed Khabiya said on Thursday.

I’ll have much more to say about all this – and the survival strategies and smuggling routes that emerged in response – in my next post, but memories of the bounty of the region haunt those who inhabit its now ruined landscape. ‘The area was once known for its intense carpet of fruit trees, vegetables and maize,’ wrote a former resident last month, but today ‘Ghouta is a scene of grey death.’ And here is a local doctor talking to the BBC just last weekend:

The place where Dr Hamid was born and raised had been abandoned to its own slow death… It was a place that people came to from Damascus, with their wives and husbands and children, for weekend picnics, or to shop for cheap merchandise in the bustling markets. “They came here from all around to smell the fresh air and the rivers and the trees,” he said. “To me it was a paradise on the Earth.” Now he prays in his cramped shelter at night that his children will one day see the place he can still conjure in his mind, “as green as it was when I was a boy”. “It may be too late for me,” he said, “but God willing, our children will see these days.”

Political rebellion and political violence

In the 1920s the Ghouta was a springboard for Syrian nationalism and its ragged, serial insurgency against French colonial occupation – ‘its orchards and villages provided sustenance for the insurgency of 1925’, wrote Michael Provence in his account of The Great Syrian Revolt, while hundreds of villagers in the Ghouta were killed or executed during the counterinsurgency. He continued:

Despite months of agitation and countless pamphlets and proclamations, the French bombardment of Damascus ended any organized mobilization in the city. The city’s destruction indelibly underscored the inability of the urban elite to lead resistance. But the effects of the bombardment were not what [French] mandate authorities had hoped. Resistance shifted back to the Ghuta and the surrounding countryside. The destruction of their city failed to pacify the population with fear and led to an outraged expansion of rebel activity, especially among the more humble inhabitants. Guerrilla bands soon gained control of the countryside on all sides of the city. They continually cut the lines of communication by road, telephone, and train, on all sides of the city Damascus went days on end virtually cut off from outside contact. Large areas of the old city were in rebel hands night after night. Contemporary sources document that the southern region was completely under the control of the insurgents. It took more than a year, and massive reinforcements of troops and equipment, for the mandatory power to regain effective control of the countryside of Damascus.

(You can find much more on French counterinsurgency and colonial violence in David Nef‘s Occupying Syria under the French Mandate: insurgency, space and state formation (Cambridge, 2012)).

Abu Ahmad, an activist from Kafr Batna, recalling that ‘Eastern Ghouta has always been at the heart of revolutionary struggles in Syria’, drew a direct line of descent from the Syrian Revolt to the mass mobilisations against the Assad regime during the Arab Spring. He insisted that the contemporary rebellion in the Ghouta had retained its independent spirit: keeping its distance from international power-brokers, so he claimed, it was ‘one of the last arenas of a real civil war’ – so much so, that its fall ‘would spell the end of the original battle between the government and the opposition.’

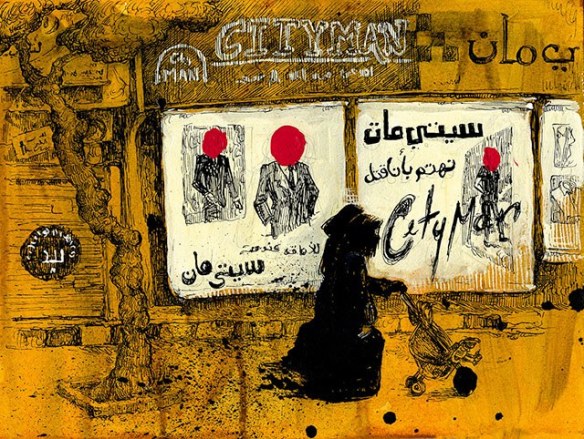

This time around these have been vigorously urban as well as rural movements. After independence from France in 1946, in the north and west of the Ghouta, closer to Damascus, agriculture gave way to a peri-urban fringe: a scatter of hard-scrabble, cinder and concrete block towns (above). Aron Lund takes up the story:

Wheat fields were crisscrossed by roads and power lines, while factories, army compounds, and drab housing projects spread out of the city and into the countryside. The ancient oasis seemed destined to disappear.

Douma, which had for hundreds of years been a small town of mosques and Islamic learning, grew into a city in its own right. Many villages were swallowed up by the capital, with, for example, Jobar—once a picturesque multi-religious hamlet where Muslims and Jews tended their orchards—transformed into a series of mostly unremarkable city blocks on the eastern fringes of Damascus….

Throughout the first decade of the new century, slum areas around Damascus expanded rapidly as the capital and its satellite towns took in poor migrants, while spiraling living costs forced parts of the Damascene middle class to abandon the inner city for a congested daily commute. It was as if every driver of anti-regime resentment in the late Assad era had congregated on the outskirts of Damascus: political frustration, religious revanchism, rural dispossession, and downward social mobility.

When the Arab uprisings swept into Syria in March 2011, the comparatively affluent and carefully policed central neighborhoods of the capital hardly stirred—but the Ghouta rose fast and hard in an angry, desperate rebellion.

The scenario was a bleakly familiar one, and followed the script established by the security forces in response to protests in Dara’a, close to the border with Jordan, in February 2011 (see here and here). One of the most serious incidents took place after Friday prayer on 1 April, when protesters emerged from the Great Mosque in Douma to join a demonstration against the regime (above) in the central square. They were greeted by hundreds of riot police, who fired teargas into the crowd, beat protesters with sticks and shocked bystanders with cattle prods. Towards the middle of the afternoon the violence escalated; rocks were thrown by some demonstrators, and the police (including snipers on the rooftops) opened fire with Kalashnikovs: 15 and perhaps as many as 22 people were killed and hundreds injured. According to one local journalist:

“This was the systematic killing of peaceful and unarmed citizens by security forces,” said Radwan Ziadeh, head of the Damascus Centre for Human Rights, one of several organisations that has collated matching witness accounts of the incident.

Witnesses [said] that thugs were bussed in by government forces to attack demonstrators [These armed thugs act as a private pro-Assad militia, known in Syria as al- Shabeha, ‘the ghosts’]. Journalists and diplomats were prevented from reaching the area over the weekend, and phone lines to Damascus have been disrupted.

In another familiar response, the same journalist reported that state news agencies had claimed that ‘armed groups’ had opened fire and that some of the demonstrators ‘had daubed their clothes with red dye to make foreign reporters believe that they had been injured.’

Local people encircled the Hamdan hospital to try to prevent the security forces gaining access to the wounded seeking treatment. One local source told Hugh Macleod and Annasofie Flamand:

“This is the last way we have to protect our wounded from being kidnapped by secret service…

“We held the line until live fire was used and we had to run and hide. I saw the secret police break into the hospital and later when I went back to the hospital some of the bodies and some of the injured were missing.”

The National Hospital and the al-Noor Hospital were also raided by security forces on 1 April searching for injured protesters. And, taking another leaf from the Dara’a playbook, all doctors were ordered to refuse treatment to the wounded; those discovered to have disobeyed were arrested, including the director of Hamdan.

The protests gathered momentum, and by September the first brigades of the Free Syrian Army had formed in Eastern Ghouta – ‘ostensibly’, Amnesty International said, ‘to protect the protesters from Syrian government forces.’

By the time Christine Marlow reported from Douma in December 2011 the city was cordoned off from Damascus by six military checkpoints (above: a Syrian Arab Army checkpoint at Douma in January 2012) and the town was effectively under martial law:

Military trucks stood parked at the end of the dark empty street. The electricity was cut, the phone signals out and apartment windows boarded up with whatever wood or metal people could find. It was to stop the bullets, activists explained. Shouting and chanting of “down down Bashar al Assad” could be heard in the distance, interspersed with the crackle of gunfire. This is not Homs, Idlib, or any of those Syrian towns that for months have been in the throes of rebellious unrest and violent crackdown. This is Douma, a large satellite town on the edge of Damascus, the heartland of support for President Assad’s regime.

Damascus Old City continues in relative normality with the bustle of daily life. Occasional power cuts and a shortage of gas are the principal signs that all is not well. But less than seven miles away, Douma is in lockdown. Every Friday – when protests traditionally take place after prayers in the mosques, the suburb is under a military siege.

… Residents had flooded the side streets and mud paths that riddle the town. Doors of homes were left ajar, an invitation of shelter to the demonstrators. Locals passed warnings to each other; “there are dogs in that street”, they said, referring to the army.

The military was on edge – protesting voices of just 10 or so people was enough to prompt gunfire….

She visited a central hospital – I don’t know whether this was the Hamdan again – and found it dark and empty. She was told that soldiers had stormed the hospital in the dead of night. Again, I don’t know if this refers to the previous incident; I do know that Hamdan was raided several times, but so too were other hospitals in Douma: see the Centre for Documentation of Violations in Syria here.

Staff, who had been tipped off, ran to hide the wounded protesters. “We grabbed the injured, we dragged them from the back door and down the side streets,” he recalled. “We kept some in the homes of sympathisers, others – those who could move – fled. Others hid inside cupboards in the hospital. Otherwise we think they would be killed.”

Activists say hundreds of people have been injured in the months of protests. Now they are tended by volunteers working in secret clinics inside sympathisers’ homes, with whatever medicine can be smuggled in. It is not enough. Mohammed, whose name has also been changed for his protection, received a heavy blow to the head from a security official during a protest in May. With no utensils or materials, doctors in the home clinic to which he was taken were forced to staple together the gaping, bleeding wound using a piece of old wire.

This too, as I will show in a later post, was a harbinger of the desperate future, in which hospitals would be systematically bombed, medical supplies routinely removed from humanitarian convoys, and doctors – like everyone else – thrown back on their own limited resources and improvisations.

The siege of Douma – and of East Ghouta more generally – tightened, and by early 2013 the region was under the control of 16 armed opposition groups. Theirs was a complex and volatile political geography and, as I will show in my next post, their fortunes were closely tied to their involvement in the siege economy. They enjoyed considerable though not unconditional nor unwavering support from local people, but this too was a complicated and changing situation. The Assad regime, its allies and agents have often portrayed the besieged population as homogeneous, particularly after displacement reduced East Ghouta from 1.5 million to around 400,000 inhabitants at the height of the siege. In another iteration of ‘the extinction of the grey zone‘ practiced across the absolutist spectrum – from right-wing radicals in the US to Islamic State in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere – they all became ‘terrorists’. That term was made to cover a lot of baggage, including anyone who was involved in any form of resistance to the authority of the state. But even within that shrivelled sense of political legitimacy, it’s important to remember throughout the discussions that follow that there were also hundreds of thousands of civilians who were caught in the cross-fire between pro-government forces and the armed opposition groups.

Dying and the Douma Four

I do not mean that last sentence as a standard disclaimer, and the most direct way I can sharpen the point is by giving space to the (too short) story of a small group of courageous activists who made their home in Douma during the siege:

The savage repression of the Assad regime had made it impossible for the people to continue with their non-violent protests. They started to carry arms, and with that, their need for an ideology of confrontation and martyrdom started to eclipse their earlier enthusiasm for forgiveness and reconciliation.

For many civilian activists, the transformation of the Syrian uprising into what seemed like a full-blown civil war was unbearable. Of those who escaped death or detention, many decided to flee the country; and, from the bitterness of their exile, they began to tell a story of loss and disillusionment. But for Razan, Wael, and many of their close friends, these same developments called for more, not less, engagement. They argued that civilian activists had the responsibility now to monitor the actions of the armed rebels, to resist their excesses, and to set up the institutions for good governance in the liberated parts of the country. They also believed, much like their friend the renowned writer Yassin al-Haj Saleh, that their task as secularists was not to preach ‘enlightenment’ from a safe distance, but to join the more ordinary and devout folk in their struggle for a life lived with dignity. Only then could liberal secularism earn its ‘place’ in Syrian society and truly challenge its primordialist detractors.

It was these beliefs that set Razan Zaitouneh on her last journey in late April 2013. After two years of living underground in Damascus, she followed the example of Yassin al-Haj Saleh and moved to the liberated town of Douma. There, among a starving population that was constantly under shelling by the regime forces, Razan launched a project for women empowerment and a community development center, all while continuing her work in documenting and assisting the victims of the war. By August, al-Haj Saleh had already left for the north, but his wife Samira al-Khalil, Razan and her husband, and their friend, the poet and activist Nazem Hammadi were all settled in Douma, sharing two apartments in the same building. In the middle of the night of December 9 [2013], they were abducted from their new homes by a group of armed men that were later linked to Al-Nusra front and the Army of Islam. To this day, their fate and whereabouts remain unknown.

You can find out more about the Douma 4 here and here. Samira al-Khalil‘s diary of the siege of Douma in 2013 has already appeared in Arabic, and will be published in English translation later this year.

Samira wrote this in her diary:

“The world does not interfere with the fact that we are dying, it controls the ways we are dying: it does not want us dead with chemical weapons but does not protest our killing by starvation, closes the borders in the face of those who are escaping certain death with their children. It leaves them to drown in their flimsy boats—a communal death in the sea, similar to the communal death by the chemical weapon.”

And those who remained inside East Ghouta, as the header to this post says, were all dying slowly. As one aid worker inside East Ghouta put it yesterday, what has happened since has been ‘wholesale slaughter witnessed by a motionless world.’

To be continued.