I’ve praised Laleh Khalili‘s Time in the shadows before, and Jadaliyya has now reprinted an excerpt that is of renewed urgency in the face of the Israeli assault on Gaza. Laleh explains:

I’ve praised Laleh Khalili‘s Time in the shadows before, and Jadaliyya has now reprinted an excerpt that is of renewed urgency in the face of the Israeli assault on Gaza. Laleh explains:

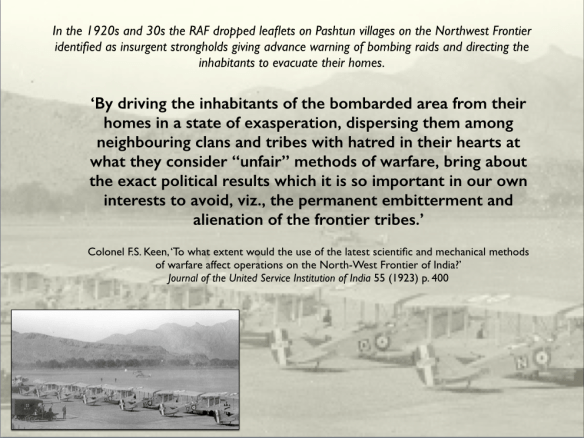

I wrote Time in the Shadows in order to puzzle out why the counterinsurgency practices of enormously powerful state militaries—the US and Israel at the time I was writing the book—so often invoked law and humanitarianism, rather than naked force. And why so much of their war-fighting pivoted around the mass confinement not only of combatants but civilians. I was also struck by the similarities in the practices of confinement not only between Israel and the US but with historical accounts of colonial confinement effected by Britain and France.

For me, what was striking, insidious, devastating, was the less flashy, less visible, practices that were foundational to detention of suspected combatants and incarceration—whether in situ or through resettlement—of troublesome civilians. These practices—law, administration, demographic and anthropological mapping, offshoring—all sounded so dry, so rational, and yet they were grist to the mill of liberal counterinsurgents in so many ways. And the other similarity across a century and several continents seemed to be the repetition ad nauseam of the language of “protection” and of “security” to frame or rename or euphemise atrocities.

Among the technologies that best embody this language of protection used to violently pacify a population in counterinsurgencies are the separation wall and the various “protective” zones invented by the Israeli military to fragment the Palestinian territories and ensure panopticon-like surveillance and monitoring capability over these fragmented zones. These technologies have specific histories and are mirrored in so many different contexts. The following excerpt is an attempt at situating the wall and the various zones in both a longer historical continuum with colonial practices, while also reflecting on the settler-colonial specificities of their present form.

Laleh describes seam zones, security zones until, finally, she arrives at death zones:

Brigadier General Zvika Fogel, the former head of Southern Command, explained that after the Second Intifada, the Southern Command unofficially declared death zones in Gaza, where anyone entering could be shot: “We understood that in order to reduce the margin of error, we had to create areas in which anyone who entered was considered a terrorist.”

Asked about the legal basis for this, Fogel said:

“When you want to use something, you have no problem finding the justification, especially when we hit those we wanted to hit when we used them at the start of the events. If at the beginning we could justify it operationally, then even if there were personnel from the Advocate General’s Office or from the prosecution, it was easy to bend them in the face of the results…

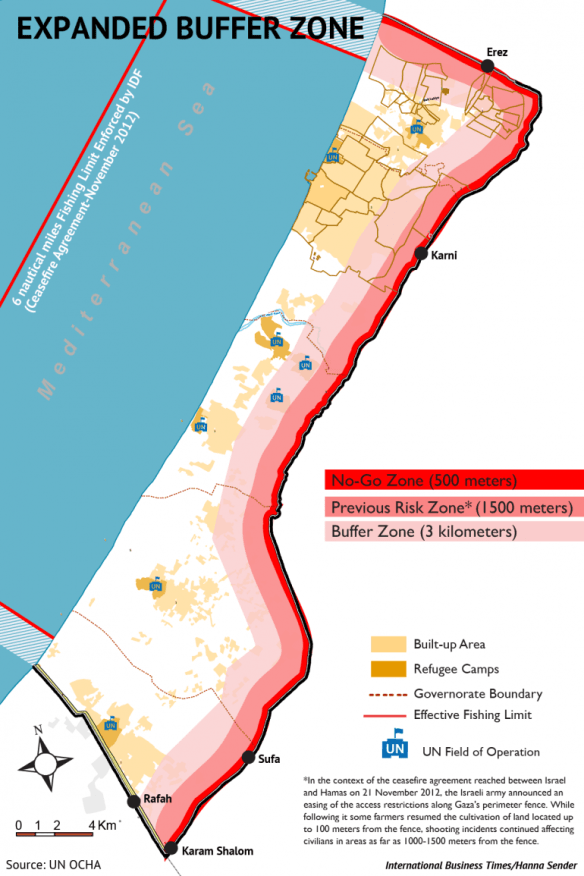

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, the Israeli military unilaterally implemented an undefined “no-go” zone inside Gaza in 2000. It started to level lands near the border fence (which had been put in place in 1994), particularly around Rafeh, and ‘by mid-2006 Israel was leveling lands 300 to 500 meters from the fence.’ In 2010 the World Food Programme in collaboration with OCHA produced a report, ‘Between the Fence and a Hard Place‘, documenting the hardships and the horrors and in 2011 Diakonia produced a detailed report on the (il)legal armature of the buffer zone, ‘Within Range‘. It concluded:

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, the Israeli military unilaterally implemented an undefined “no-go” zone inside Gaza in 2000. It started to level lands near the border fence (which had been put in place in 1994), particularly around Rafeh, and ‘by mid-2006 Israel was leveling lands 300 to 500 meters from the fence.’ In 2010 the World Food Programme in collaboration with OCHA produced a report, ‘Between the Fence and a Hard Place‘, documenting the hardships and the horrors and in 2011 Diakonia produced a detailed report on the (il)legal armature of the buffer zone, ‘Within Range‘. It concluded:

The use of force based on military necessity must be engaged in good faith and consistent with other rules of IHL, in particular the principles of distinction and proportionality and precautions in and during attack. This does not appear to be the case in the “buffer zone” as the violations to IHL are flagrant, frequent and grave. Israel remains the Occupying Power in the Gaza Strip. In this capacity, it must protect the safety and well-being of the Palestinian population and take Palestinian needs into account. In addition, Israel must also protect Israeli civilians and soldiers, but it is not allowed to do so at disproportionate expense to Palestinian civilian lives and property.

While acknowledging Israel’s security concerns regarding attacks on Israel from the Gaza Strip, the facts and information available show that the unilateral expansion of the “buffer zone” and its enforcement regime result in violations of international humanitarian law and grave infringement of a number of rights of Palestinians.

In 2012 OCHA estimated that up to 35 per cent of Gaza’s agricultural land had been affected by these restrictions at various times, and the Gazan economy had sustained a loss of around 75,000 MT of agricultural produce each year ($50 million p.a.)

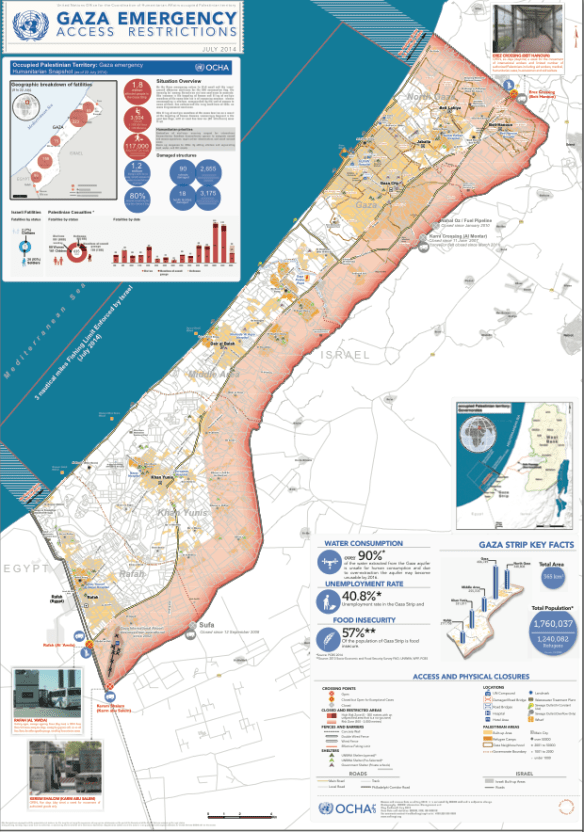

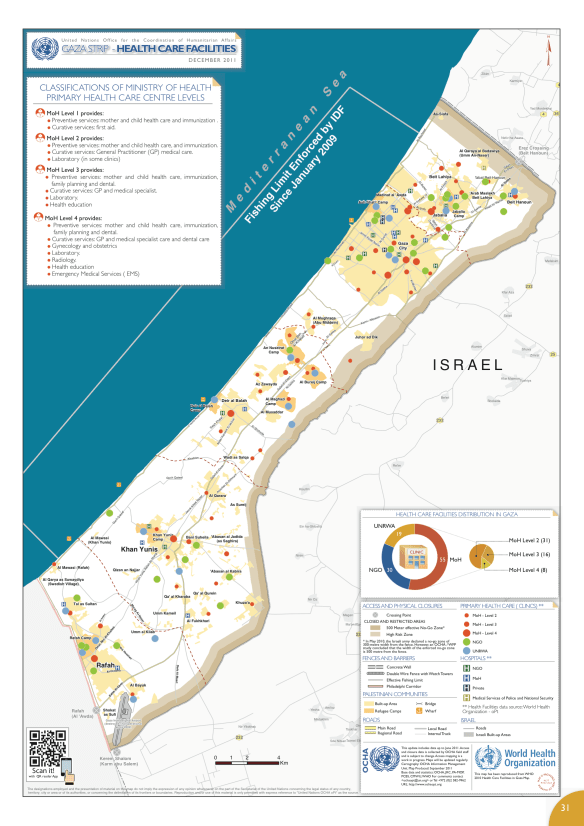

The situation in December 2012 is set out on the map below, which shows what the Israeli military defined as ‘Access Restricted Areas’ (ARA) which, on the landward side, comprised three zones:

(1) A ‘No-Go Zone’, 100 metres wide, which was cleared of all vegetation and all built structures;

(2) A ‘restricted zone’, a further 100-300 metres wide, where access was permitted on foot and for farmers only;

(3) A ‘risk zone’…

You can download a hi-res version here (see also Léopold Lambert‘s maps and commentary here). In practice, the UN Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights explained, ‘the “no go zone’’ on land was at times enforced a few hundred metres beyond this, with a “high risk zone” extending sometimes up to 1,500 metres.’ In November 2012 these restrictions were supposed to be eased, as part of the agreement ending the Israeli offensive earlier that month. But as the Commissioner reported, ‘there has been an increased level of uncertainty regarding the access restrictions imposed on land since this date.’ In the spring UN monitoring teams reported that in most cases farmers could not enter lands within 300 metres of the fence and that the Israeli military fired warning shots if they attempted to do so, that in some places the exclusion zone extended beyond 300 metres, and that there was continued concern about the presence of unexploded ordnance in the border areas. The map produced by Gisha: Legal Center for Freedom and Movement for September 2013, ‘Mapping movement and access‘, reflects these realities, and you can find a detailed report from the Palestinian Center for Human Rights and the IDMC, Under Fire: Israel’s enforcement of access restricted areas in the Gaza Strip (February 2014) here.

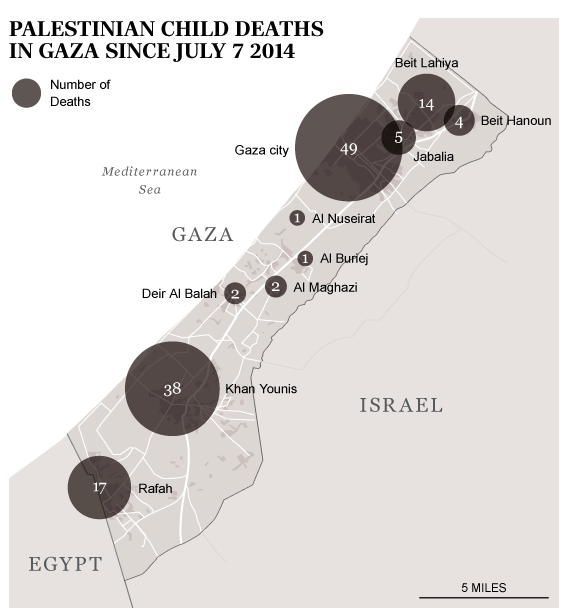

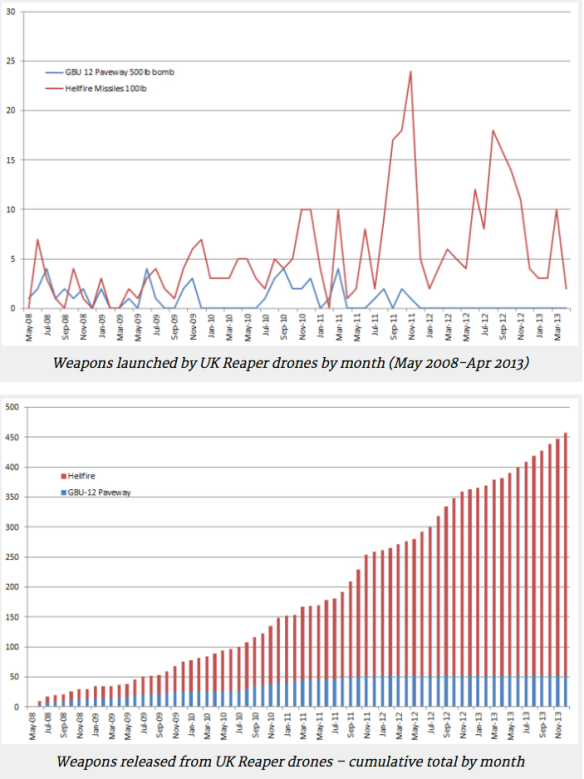

Unexploded ordnance is a matter of grave concern, but there has also been a history of live-fire incidents (see the graph below). Since December 2013 and before the current Israeli offensive the number of live-fire casualties near the fence was increasing again. In a ten week period between December 2013 and March 2014 B’Tselem field researcher Muhammad Sabah documented 55 civilians injured near the fence: 43 by live fire; 10 by rubber bullets; and two hit by teargas canisters [I can’t link to the report at the moment because the B’Tselem website is under attack and has been taken off the grid; I can now – it’s here].

These live-fire incidents are sometimes carried out from remote-controlled stations; the system is called ‘Spot and Strike‘. Michael Morpurgo, the creator of “War Horse”, saw its effects when he visited Gaza in November 2010 as a representative of Save the Children:

“I stood in among the ruins watching the kids at work, coming and going with their donkeys and carts. They didn’t seem worried, so I wasn’t worried… I heard the shots, then the screaming, saw the kids running to help their wounded friends. Now I really was outside the comfort zone of fiction. A doctor from Medecins Sans Frontieres told me that the shots were not fired by snipers from the watchtowers on the wall, as I had supposed, but that these scavengers were routinely targeted, electronically from Tel Aviv, which was over 25 kilometres away – ‘Spot and Strike’, the Israelis call it.

“It was like a video game – a virtual shooting, only it wasn’t: there was blood, his trousers were soaked in it, the bullets were real. I saw the boy close to, saw his agony as the cart rushed by me. Many like him, the doctor told me, ended up maimed for life. Here was a child, caged and under siege, being deliberately targeted, his right to survival, the most basic of all children’s rights, being utterly ignored. Unicef says that 26 children were shot like this in 2010. The boy I saw was called Shamekh, I discovered. He lives in a house with 15 family members, and was out there earning what money he could, in the only way he knew how.’

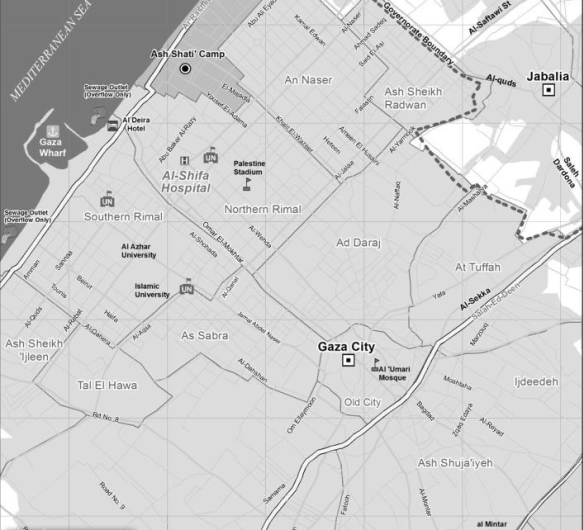

Today, there is a palpable sense in which the whole of Gaza has become a death zone. First, Israel has declared a three-kilometre ‘buffer zone’ inside Gaza’s borders which now effectively places 44 per cent of the territory off limits (you can download the OCHA map below here; the second map makes the situation clearer, though it inevitably sacrifices detail). Compare this with the previous map by following the line of the road south-north.

Léopold Lambert has provided this close-in triptych which exposes the enormity of the expansion and the knock-on effects of the forced displacement:

Mohammed Omer reports:

Anyone within the zone has been warned by the Israeli military to leave or risk being bombed.

This buffer zone has only exacerbated Gaza’s siege. To the east, Palestinians in Gaza are fenced in by Israeli artillery tanks, mortars, cannon shells and snipers. On Gaza’s western side, Israeli warships form a blockade and allow only a three-mile fishing zone. To the north resides more military checkpoints and soldiers. To the south, the Egyptian military has closed off the Rafah border.

The buffer zone has tightened the Israeli chokehold around Gaza’s small strip of land.

This is, as Jesse Rosenfed reports, a ‘No Man’s Land’ in exactly the expanded sense proposed by Noam Leshem and Al Pinkerton:

This is, as Jesse Rosenfed reports, a ‘No Man’s Land’ in exactly the expanded sense proposed by Noam Leshem and Al Pinkerton:

What that means on the ground is scenes of extraordinary devastation in places like the Al Shajaya district approaching Gaza’s eastern frontier, and Beit Hanoun in the north. These were crowded neighborhoods less than three weeks ago. Now they have been literally depopulated, the residents joining more than 160,000 internally displaced people in refuges and makeshift shelters. Apartment blocks are fields of rubble, and as I move through this hostile landscape the phrase that keeps ringing in my head is “scorched earth.”

It’s not like Israel didn’t plan this. It told tens of thousands of Palestinians to flee so its air force, artillery and tanks could create this uninhabitable no-man’s land of half-standing, burned-out buildings, broken concrete and twisted metal. During a brief humanitarian ceasefire some Gazans were able to come back to get their first glimpse of the destruction this war has brought to their communities, and to sift through their demolished homes to gather clothes or other scattered bits of their past lives. But many were not even able to do that.

Satellite imagery has confirmed the scale of the devastation; the map (right) is based on just three areas within the expanded ‘buffer zone’ and was compiled from imagery taken before the intensification of the onslaught. You can find details of the UNITAR/UNOSAT programme and image files here. If you can bear to get closer, there are photographs taken on the ground here and here.

Second, the Israeli military have not confined their operations to the expanded buffer zone, and those who have – somehow – found sanctuary outside its limits (but of necessity still within the closed and shuttered confines of Gaza) have found that they are pursued by aircraft and tanks. The image below, taken from the same source (and same date) used to compile the map above, shows a wide arc of damage in central Gaza far beyond the ‘zone’ (see also my previous posts here, here and here; you can also find a detailed interactive photo-map of the whole territory from the New York Times here).

‘The problem,’as one young resident explained to Anne Barnard, ‘is that when we are fleeing from the shelling, we still find the shelling around us.’ Stories abound of families seeking refuge only to find death waiting for them. One man told Alexandra Zavis that his brother, four sisters, brother-in-law and five young children escaped from eastern Gaza to what they thought was a safe place in central Gaza City, only to be killed when the top floors of the building collapsed after an Israeli air strike the very next day. Others tell similar stories – one family moving twice before eventually ten of them were killed. And then there are all those who have sought refugee in UNRWA camps, many of them schools, or who have been rushed to hospitals for treatment, only to be bombed and shelled there too.

Ha’aretz‘s headline on 31 July says it all: ‘The Gaza battlefield is crowded with the displaced and the homeless.’ So it is. And still they are bombed and shelled. As UNRWA’s Chris Gunness put it, ‘Gaza is unique in the annals of modern warfare in being a conflict zone with a fence around it, so civilians have no place to flee.’

In his seminal essay on ‘Necropolitics‘, written more than ten years ago, Achille Mbembe had this to say:

Late-modern colonial occupation differs in many ways from early-modern occupation, particularly in its combining of the disciplinary, the biopolitical, and the necropolitical. The most accomplished form of necropower is the contemporary colonial occupation of Palestine…

Entire populations are the target of the sovereign. The besieged villages and towns are sealed off and cut off from the world. Daily life is militarized… The besieged population is deprived of their means of income. Invisible killing is added to outright executions…

I have put forward the notion of necropolitics and necro-power to account for the various ways in which, in our contemporary world, weapons are deployed in the interest of maximum destruction of persons and the creation of death-worlds, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead.

Gaza has been systematically turned not only into a prison, then, but also into a camp: and the lives of those within have been have been subjected to a ruthless bio-political programme that, at the limit, has become a calculated exercise in necro-politics. This confirms Paul Di Stefano‘s claim that that, for the Israeli military, Gaza has been transformed into ‘a state of exception where normal rights do not apply. Within this liminal space, Palestinian bodies are viewed as obstacles to be destroyed or controlled in the maintenance of the colonial order.’