In my preliminary commentary on the US military investigation into the air strike on MSF’s trauma centre in Kunduz in October 2015 – and I’ll have much more to say about that shortly – I circled around the Pentagon’s conclusion that even though those involved in the incident had clearly violated international humanitarian law (‘the laws of war’) and the Rules of Engagement no war crimes had been committed.

That conclusion has sparked a fire-storm of protest and commentary, and to track the narrative I’ve transferred some of my closing comments from that post to this and continued to follow the debate. (It’s worth noting that when the Pentagon published its updated Law of War Manual last year it produced an equally heated reaction – much of it from commentators who complained that its provisions hamstrung commanders and troops in the field: see here and scroll down).

At Just Security Sarah Knuckey and two of her students complained that the report provided no justification for such a claim. After listing the gross violations of IHL (failure to take precautions in an attack, failure to distinguish between civilians and combatants, failure to respect the requirement of proportionality), they concluded:

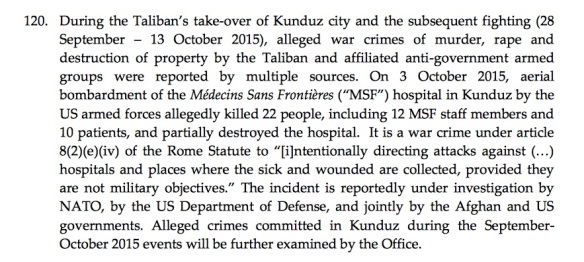

While it is legally correct to state that the war crime of murder requires an “intent” to kill a protected person (e.g., a civilian), nowhere in the 120-page report is there an analysis of the legal meaning of “intention.” The report actually makes no specific or direct findings about war crimes. (“War crime” appears only once, in reference to a report by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan) [Here I should note that UNAMA’s view of what constitutes a war crime has on occasion changed with the perpetrator. As this commentary shows, the Taliban have sometimes been held to a higher standard than the US military: in one case UNAMA suggested that the very use of high explosives in an urban area ‘in circumstances almost certain to cause immense suffering to civilians’ rendered the Taliban guilty of war crimes, whereas after the Kunduz air strike UNAMA declared that ‘should an attack against a hospital be found to have been deliberate, it may amount to a war crime’ (emphasis added)] .

Under international law, “premeditation” is not necessary for the war crime of murder, but the precise scope of intention is less clear. Numerous cases have stated that genuine mistakes and negligence are insufficient for murder. But a number of international cases and UN-mandated inquiries have found that “recklessness” or “indirect intent” could satisfy the intent requirement. Article 85 of Additional Protocol I also provides that intent encompasses recklessness. (See The 1949 Geneva Conventions: A Commentary, from page 449, for a full discussion.)

The investigation released today makes clear that US forces committed numerous violations of fundamental rules of the laws of war, violations which should and could have been avoided. Yet the report provides zero direct analysis of whether these violations amounted to war crimes. Given the seriousness of the violations committed, the US should specifically explain why the facts do not amount to recklessness, and explain the legal tests applied for the commission of war crimes.

Over at Lawfare, Ryan Vogel argues that the report will ‘will surely attract the attention of the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) Office of the Prosecutor (OTP)’. In fact, while the OTP has acknowledged

that the strike was being investigated by the United States [it has also] declared that “the [a]lleged crimes committed in Kunduz [would] be further examined by the Office” as part of the ongoing preliminary examination [see extract below]. By characterizing the incident as a violation of international law (and choosing not to prosecute), the United States may unwittingly be strengthening the OTP’s case. It is true that CENTCOM’s release statement makes clear that the investigation found that the actions of U.S. personnel did not constitute war crimes, noting the absence of intentionality. But the OTP might disagree with CENTCOM’s legal rationale, as it seems to have done previously with regard to detention operations, and decide to investigate these acts anyway as potential war crimes.

As both commentaries make clear, much hangs on the interpretation of ‘intentionality’. At Opinio Juris the ever-sharp Jens David Ohlin weighs in on the question. Drawing from his essay on ‘Targeting and the concept of intent‘, he notes:

The word “intentionally” does not have a stable meaning across all legal cultures. … [It] is generally understood in common law countries as equivalent to purpose or knowledge, depending on the circumstances. But some criminal lawyers trained in civil law jurisdictions are more likely than their common law counterparts to give the phrase “intentionally” a much wider definition, one that includes not just purpose and knowledge but also recklessness or what civilian lawyers sometimes call dolus eventualis.

He concludes that the consequences of the latter, wider interpretation would be far reaching:

If intent = recklessness, then all cases of legitimate collateral damage would count as violations of the principle of distinction, because in collateral damage cases the attacker kills the civilians with knowledge that the civilians will die. And the rule against disproportionate attacks sanctions this behavior as long as the collateral damage is not disproportionate and the attack is aimed at a legitimate military target. But if intent = recklessness, then I see no reason why the attacking force in that situation couldn’t be prosecuted for the war crime of intentionally directing attacks against civilians, without the court ever addressing or analyzing the question of collateral damage. Because clearly a soldier in that hypothetical situation would “know” that the attack will kill civilians, and knowledge is certainly a higher mental state than recklessness. That result would effectively transform all cases of disproportionate collateral damage into violations of the principle of distinction and relieve the prosecutor of the burden of establishing that the damage was indeed disproportionate, which seems absurd to me.

His solution is to call for the codification of ‘a new war crime of recklessly attacking civilians, and the codification of such a crime should use the word “recklessly” rather than use the word “intentionally.”’ This would then ‘create a duty on the part of attacking forces and then penalize them for failing to live up to it.’ And this, he concludes, would allow a prima facie case to be made that those involved in the attack on the Kunduz trauma centre were guilty – but in his view, clearly, they also escape under existing law.

Note those five, deceptively simple words: ‘those involved in the attack’. I’ve had occasion to comment on this dilemma before – the dispersal of responsibility that is a characteristic of later modern war (see also here: scroll down) – and Eugene Fiddell, writing in the New York Times, clearly dismayed at the way in which the military inquiry was conducted, sharpens the same point:

Among the challenges a case like Kunduz presents is how to achieve accountability in an era in which an attack on a protected site is not the act of an isolated unit or individual. In today’s high-tech warfare, an attack really involves a weapons system, with only some of the actors in the aircraft, and others — with real power to affect operations — on the ground, in other aircraft, or perhaps even at sea.

And what if some of those ‘actors’ are algorithms and/or machines?

UPDATE: Kevin Jon Heller offers this counter-reading to Jens’s:

As I read it, the war crime of “intentionally directing attacks against a civilian population” consists of two material elements: a conduct element and a circumstance element. (There is no consequence element, because the civilians do not need to be harmed.) The conduct element is directing an attack against a specific group of people. The circumstance element is the particular group of people qualifying as a civilian population. So that means, if we apply the default mental element provisions in Art. 30, that the war crime is complete when (1) a defendant “means to engage” in an attack against a specific group of people; (2) that specific group of people objectively qualifies as a civilian population; and (3) the defendant “is aware” that the specific group of people qualifies as a civilian population. Thus understood, the war crime requires not one but two mental elements: (1) intent for the prohibited conduct (understood as purpose, direct intent, or dolus directus); (2) knowledge for the necessary circumstance (understood as oblique intent or dolus indirectus).

Does this mean that an attacker who knows his attack on a military objective will incidentally but proportionately harm a group of civilians commits the war crime of “intentionally directing attacks against a civilian population” if he launches the attack? I don’t think so. The problematic element, it seems to me, is not the circumstance element but the conduct element: although the attacker who launches a proportionate attack on a legitimate military objective knows that his attack will harm a civilian population, he is not intentionally attacking that civilian population. The attacker means to attack only the military objective; he does not mean to attack the group of civilians. They are simply incidentally — accidentally — harmed. So although the attacker has the mental element necessary for the circumstance element of the war crime (knowledge that a specific group of people qualifies as a civilian population) he does not have the mental element necessary for its conduct element (intent to attack that specific group of people). He is thus not criminally responsible for either launching a disproportionate attack or intentionally directing attacks against a civilian population.

It’s a sharp reminder that international humanitarian law offers some protections to civilians but still renders their killing acceptable. The exchange between Kevin and Jens continues below the line to this conclusion:

But if you read Charles Dunlap at Lawfire (sic), you will find him insisting that the mistakes made by the US military in firing on the MSF hospital ‘do not necessarily equate to criminal conduct’ – even though the investigation report concedes that they amounted to violations of international law – and that the charge of recklessness needs to be laid at the smashed-in door of MSF. Really. Here is what he says:

Had, for example, the hospital been marked with large Red Crosses/Red Crescents or one of the other internationally-recognized symbols (as the U.S. does) or something that would make its protected use clear from the air, isn’t it entirely plausible that the aircrew (or someone) might have recognized the error and stopped the attack before it began?

There were in fact two large MSF flags on the roof of the Trauma Centre, which was also one of the few buildings in the city on that fateful night to have been fully illuminated (from its own generator).

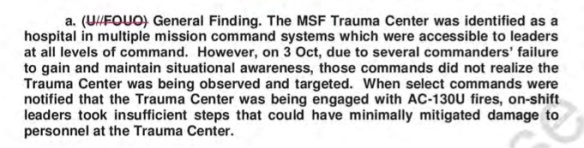

But in case you are still wondering about the responsibility borne by MSF – as ‘one of the few international humanitarian organisations that carries professional liability insurance’ (in contrast to amateur insurance, I presume), Dunlap says that is an admission that ‘even honest, altruistic, and well-intended professionals do make mistakes, even tragic ones, especially when trying to operate in the turmoil of a war zones’, here is a paragraph from that investigation report:

How reckless was that? The crew of the gunship that carried out the attack – in case you are still wondering – ‘specifically did not have any charts showing no strike targets or the location of the MSF Trauma Center.’

And if you picked up on Dunlap’s suggestion that if not the aircrew then ‘someone’ might have recognised the error, try this for size from the same source (and note especially the last sentence):

More to come.