Stuart Elden alerts us to Anti-Security… where you will find this:

This is an important project…

The US/Mexico borderlands was one of the sites I discussed in ‘The everywhere war’ (see DOWNLOADS tab), along with the Afghanistan/Pakistan borderlands and cyberspace. It’s also another zone where the blurring of policing and military operations is highly visible.

For the book I plan to separate these three into three chapters, which I’m hoping will produce a more nuanced, certainly less cartoonish discussion – inevitable, I suppose, in such a short essay (and written – for me – in an unusually short time, though editor Klaus Dodds may not have seen it quite like that…). So I’ve been gathering materials, and en route found a short, sharp documentary from Real Television News [‘No advertising, no corporate funding’ – and really excellent] that debunks claims of ‘spillover violence’, at least from Mexico into the US. It asks ‘Is the Arizona/Mexico border a war zone?’

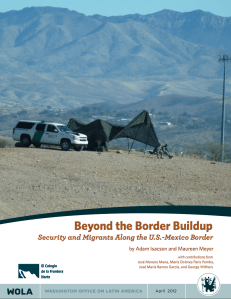

The Washington Office on Latin America, an NGO ‘promoting human rights, democracy and social justice’ founded in response to the military coup in Chile in 1973, has a fact-checking blog on the securitization of the border, and this year published Beyond the Border Buildup: Security and migrants along the US Mexico border.

The Washington Office on Latin America, an NGO ‘promoting human rights, democracy and social justice’ founded in response to the military coup in Chile in 1973, has a fact-checking blog on the securitization of the border, and this year published Beyond the Border Buildup: Security and migrants along the US Mexico border.

The study finds a dramatic buildup of U.S. security forces along the southern border – a fivefold increase of the Border Patrol in the last decade, an unusual new role for U.S. soldiers on U.S. soil, drones and other high-tech surveillance, plus hundreds of miles of completed fencing – without a clear impact on security. For instance, the study finds that despite the security buildup, more drugs are crossing than ever before.

Furthermore, the study reveals that security policies that were designed to combat terrorism and drug trafficking are causing a humanitarian crisis and putting migrants in increasing danger. Migrants are often subject to abuse and mistreatment while in U.S. custody, and face higher risks of death in the desert than in previous years. Also, certain deportation practices put migrants at risk. For example, migrants can be deported at night and/or to cities hundreds of miles from where they were detained. These same cities are also some of the border region’s most dangerous, where migrants may fall prey to – or be recruited by – criminal groups. In Mexico, approximately 20,000 migrants are kidnapped a year; many others face other abuses.

WOLA found that any further increase in the security buildup will yield diminishing returns. Contrary to common opinion, the report documents a sharp drop in migrant crossings. Since 2005, the number of migrants apprehended by the Border Patrol has plummeted by 61 percent, to levels not seen since Richard Nixon was president. Today, twenty migrants are apprehended per border patrol agent per year, down from 300 per agent per year in 1992.

Finally, the study finds that violence in Mexico is not spilling over to the U.S. side of the border. U.S. border cities experience fewer violent crimes than the national average, or even the averages of the border states. WOLA recommends that before making further investments in border security, the U.S. government should stop and take stock of what is and isn’t working in order to create a comprehensive strategy that takes addresses the real threats while respecting the human rights of migrants.

Then I turn to the pages of the latest Military Review, where Christopher Martinez elaborates on Mexico’s transnational criminal organisations – the drug cartels – as constituting a commercial insurgency: ‘They seek to influence the four primary elements of national power — the economy, politics, the military, and the information media — to form an environment that enables an illicit trafficking industry to thrive and operate with impunity.’ Martinez is not the first, and he certainly won’t be the last, to describe Mexico’s militarized ‘war on drugs’ in terms of insurgency and counterinsurgency and, as I showed in ‘The everywhere war’, this rhetoric slides easily into the armature of a ‘border war’ in which the United States is fully invested as part of its boundless ‘war on terror’.

But what is most interesting about the MR essay is its author: Major Martinez is described as ‘the senior military intelligence planner for the U.S. Southwest Regional Support team at Joint Task Force North, Fort Bliss, TX’ who ‘serves as an advisor and partner to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies in Arizona and California.’

JTF-North, part of US Northern Command, provides military support to federal law enforcement agencies. Described as a ‘force multiplier’ by one Border Patrol officer, the function of its ground troops – like the unarmed Predators deployed by the Border Patrol – is limited to surveillance and under the Posse Comitatus Act the US military is not allowed to ‘execute the laws’ without express Congressional approval. As one Army officer explained, therefore, in a recent exercise troops ‘used their state-of-the-art surveillance equipment to identify and report the suspected illegal activities they observed and vectored border patrol agents in to make the arrests and drug seizures.’ But the practices, co-ordinated from a tactical operations center like the one shown on the left, are portable and even interchangeable:

JTF-North, part of US Northern Command, provides military support to federal law enforcement agencies. Described as a ‘force multiplier’ by one Border Patrol officer, the function of its ground troops – like the unarmed Predators deployed by the Border Patrol – is limited to surveillance and under the Posse Comitatus Act the US military is not allowed to ‘execute the laws’ without express Congressional approval. As one Army officer explained, therefore, in a recent exercise troops ‘used their state-of-the-art surveillance equipment to identify and report the suspected illegal activities they observed and vectored border patrol agents in to make the arrests and drug seizures.’ But the practices, co-ordinated from a tactical operations center like the one shown on the left, are portable and even interchangeable:

While providing the much needed support to the nation’s law enforcement agencies, the JTF North support operations provide the volunteer units with real-world training opportunities that are directly related to their go-to-war missions.

“This type of experience is impossible to replicate in a five- or 10-day field exercise back home,” said Lt. Col. Kevin Jacobi, squadron commander. “Where else can we operate over an extended period of time, in an extended operating environment, against a thinking foe who is actively trying to counter us by actively trying to hide, in order to make us work hard to find him?” asked Jacobi.

Not surprisingly, there have been elaborate circulations between the Afghanistan/Pakistan borderlands and the US/Mexico border: Predators, personnel and procedures. All of which provides another disquieting answer to the question posed in the RTN video…

Does this also return us to the world mapped by Mark Neocleous from my previous post? He concludes:

‘From a critical perspective, the war-police distinction is irrelevant, pandering as it does to a key liberal myth. Holding on to the idea of war as a form of conflict in which enemies face each other in clearly defined militarized ways, and the idea of police as dealing neatly with crime, distracts us from the fact that it is far more the case that the war power has long been a rationale for the imposition of international order and the police power has long been a wide-ranging exercise in pacification.’

There is growing interest in thinking through the contemporary blurring of policing and military violence. When, I wonder, did we start referring to “security forces“? The earliest entry in the OED is from 1973 and refers to Britain’s military/police operations in Northern Ireland, but the practice is evidently much older than that. Those who grew up in Britain with Biggles (or perhaps in spite of Biggles) will surely remember Captain W.E. Johns‘s creation of the Special Air Police after the Second World War – and, as my illustration (left) from Biggles Flies East implies, these operations were about the violent production of particular spatialities – but ‘air control’ was developed as an important police/military modality of British colonial power immediately after the First World War, when its prized sphere of operations was the Middle East and India’s North West Frontier (notably Waziristan).

There is growing interest in thinking through the contemporary blurring of policing and military violence. When, I wonder, did we start referring to “security forces“? The earliest entry in the OED is from 1973 and refers to Britain’s military/police operations in Northern Ireland, but the practice is evidently much older than that. Those who grew up in Britain with Biggles (or perhaps in spite of Biggles) will surely remember Captain W.E. Johns‘s creation of the Special Air Police after the Second World War – and, as my illustration (left) from Biggles Flies East implies, these operations were about the violent production of particular spatialities – but ‘air control’ was developed as an important police/military modality of British colonial power immediately after the First World War, when its prized sphere of operations was the Middle East and India’s North West Frontier (notably Waziristan).

In the 1950s Britain applied similar (il)logics to the the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya, as Clive Barnett notes here (with another, rather more serious nod to Biggles), and to the Malayan Emergency. Bombing was a routine tactic in all these pre- and post-war campaigns – the image on the right is of an RAF briefing in Kenya in 1954 – and Britain’s ‘aerial supremacy’ was, of course, uncontested in these colonial theatres of war. Other colonial powers used it too. No doubt the interest shown by the US Border Patrol and US police forces in (at present, unarmed) drones can be situated within this techno-political history of air policing, though I’m aware that the lines of descent are more complicated than my cartoons can suggest.

In the 1950s Britain applied similar (il)logics to the the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya, as Clive Barnett notes here (with another, rather more serious nod to Biggles), and to the Malayan Emergency. Bombing was a routine tactic in all these pre- and post-war campaigns – the image on the right is of an RAF briefing in Kenya in 1954 – and Britain’s ‘aerial supremacy’ was, of course, uncontested in these colonial theatres of war. Other colonial powers used it too. No doubt the interest shown by the US Border Patrol and US police forces in (at present, unarmed) drones can be situated within this techno-political history of air policing, though I’m aware that the lines of descent are more complicated than my cartoons can suggest.

Mark Neocleous has outlined a careful (and still longer) genealogy of the very idea of ‘policing’ that speaks directly to these issues in ‘The Police of Civilization: The War on Terror as Civilizing Offensive’, International Political Sociology 5 (2011) 144-159:

The monopoly over the means of violence that is fundamental to the fabrication of social order is the core of the police power. Although such a formal monopoly over the means of violence does not exist in the international realm—which is the very reason why so many people have found it difficult to develop the concept of ‘‘international police’’—the violence through which this realm has been structured is obvious. It has traditionally been cast under the label ‘‘war.’’…

To say that police and war conjointly form the key activity of the project of civilization is to say nothing other than violence has remained intrinsic to the process in question. Thus, central to the idea of civilization is military-police terror (albeit, as ‘‘civilization,’’ a terror draped in law and delivered with good manners)…

The attempt to hold on to categorical distinctions between ‘‘police’’ or ‘‘military’’ for analytical, legal, and operational reasons runs the risk of losing what is at stake in the fabrication of international order: the way war imbricates itself into the fabric of social relations as a form of ordering the world, diffracting into a series of micro-operations and regulatory practices to ensure that nebulous target ‘‘security,’’ in such a way that makes war and police resemble one another.

If, as I’ve suggested, these formulations have a direct bearing on counterinsurgency – and not only British practices: see Neocleous on Vietnam here – and on the modalities of modern colonial power more generally, they are also revealed with remarkable clarity in the contemporary city: what Steve Graham calls ‘Foucault’s boomerang’, as colonial tactics are repatriated to the metropolis.

As Steve shows in exemplary detail in Cities under siege: the new military urbanism (Verso, 2010; paperback out now), a vital zone of convergence between police and military violence – what Neocleous calls their ‘violent fabrication of the world’, their ordering of it in every sense of the verb – is the city:

‘As security politics centre on anticipation and profiling as means of separating risky from risk-free people and circulations inside and outside the territorial limits of nations, a complementary process is underway. Policing, civil law enforcement and security services are melding into a loosely, and internationally, organized set of (para)militarized security forces. A “policization of the military” proceeds in parallel with the “militarization of the police”.’

So here is welcome news of a Live Web Seminar from Harvard’s Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research, Dangerous Cities: Urban violence and the militarization of law enforcement, 2 October 2012 0930-1100 (Eastern).

So here is welcome news of a Live Web Seminar from Harvard’s Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research, Dangerous Cities: Urban violence and the militarization of law enforcement, 2 October 2012 0930-1100 (Eastern).

More than half of the world’s population is concentrated in urban areas. According to UNFPA, this number is expected to rise to 5 billions by 2030, reaching 2/3 of the world population, with the largest cities emerging in Africa and Asia. Regrettably, along with this mass urbanization has come an unprecedented level of violence and crime in densely populated slums and shantytowns. Cities like Baghdad, Kingston, Rio de Janeiro, Guatemala, Ciudad Juarez and Mogadishu have become the battlegrounds of contemporary conflicts.

In many countries, particularly in Latin America, this emerging form of violence is considered one of the greatest threats to national security. Indeed, urban violence can be as deadly and costly as traditional armed conflicts. In a 2007 report, the UNODC pointed out that the levels of violence in El Salvador in 1995 were higher than during the civil war of the 1980s.

To curb the violence, states have responded by deploying specially trained military units when traditional law enforcement has failed to restore security. These instances of ongoing urban violence engaging organized criminal networks, coupled with the use of military force, increasingly resemble to situations of armed conflicts.

While the militarization of law enforcement may be unavoidable when traditional law enforcement institutions lack the resources and expertise to contain urban violence, the legal and policy framework for the conduct of such operations needs yet to be developed. The regulation of the use of military force represents a major challenge in urban environments, even more so when humanitarian law is formally inapplicable and the enforcement of international human rights is weak. Such environment may require adaptation of military doctrine, training, and equipment in order to minimize abuses against civilians, detainees and those no longer engaged in violent acts.

Furthermore, the humanitarian sector faces formidable difficulties in the context of urban violence. First, humanitarian actors must assess whether involvement in these complex situations is appropriate under their respective mandates. Second, humanitarians must develop objective criteria to determine whether the level of violence and human suffering warrants intervention in view of the specific security and policy risks. And third, humanitarian actors must adapt to these situations and identify priority areas of humanitarian action on a case-by-case basis.

In light of these considerations, this Live Web Seminar will shed light on the tensions and challenges arising out of the application of humanitarian principles in urban violence. Expert panelists and participants will explore the following questions:

– Whether instances of urban violence can be characterized as armed conflicts? If so, what are the advantages and disadvantages of applying International Humanitarian Law (IHL) to these situations?

– To what extent is it necessary to develop a legal framework that incorporates both humanitarian and human rights considerations tailored to situations of urban violence?

– What strategies and policy tools can be put in place in order to minimize human suffering and, at the same time, address the security concern of states in urban conflicts?

What is the proper role of humanitarian actors in urban conflicts?

Registration is required: go here.

As should be obvious from the pre-seminar summary, this isn’t quite the agenda that Neocleous has in mind – but it’s also clear that his suggestions should also animate continuing discussions of our so-called ‘humanitarian present‘…