Once you decide you want to engage with audiences beyond the academy – one of my reasons for starting this blog, which also spirals in to my presentations and (I hope) my other writing – you run the risk of accepting invitations to comment on issues that lie far beyond your competence. Even supposed ‘experts’ can be caught out, of course: think of Steven Emerson‘s extraordinary claim earlier this week on Fox News (where else?) that in the UK ‘there are actual cities like Birmingham that are totally Muslim where non-Muslims just simply don’t go in…’ Emerson is the founder and Executive Director of the Investigative Project on Terrorism, and ‘is considered one of the leading authorities on Islamic extremist networks, financing and operations’ – or so he says on his website – and he subsequently apologised for his ‘inexcusable error’.

Emerson was being interviewed as part of Fox News’s continuing coverage of the murders at the office of Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket in Paris on 7 January, and specifically about the supposed proliferation of what he called ‘no-go zones … throughout Europe’.

A good rule is to treat areas you know nothing about as ‘no-go zones’ until you’ve done the necessary research.

Academics need to take that seriously too, especially as universities become ever busier pumping up their public affairs, boosting their media profiles and offering journalists ready access to the specialised knowledge of their faculty. Don’t get me wrong: I believe passionately in the importance of public geography, especially with a little g, and I also understand how producers and journalists racing to meet a deadline need talking heads. But we need to be careful about the simulation of expertise.

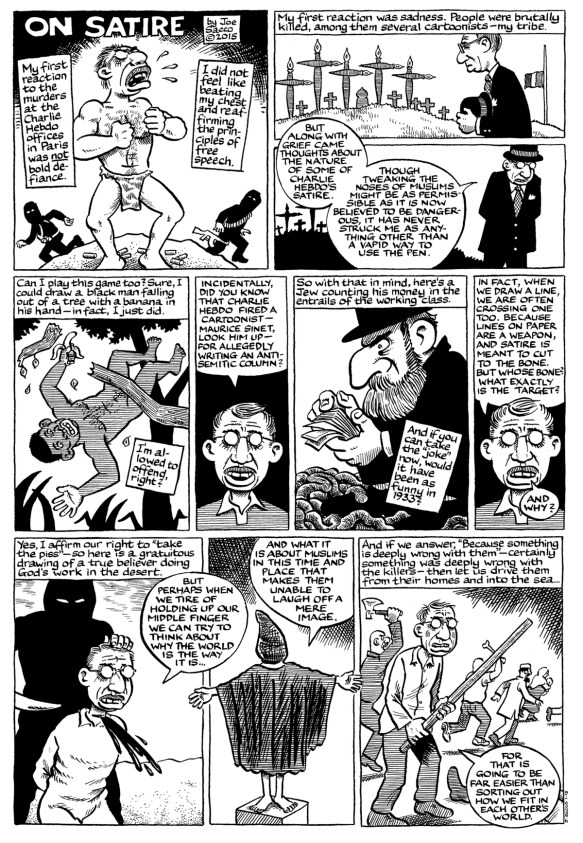

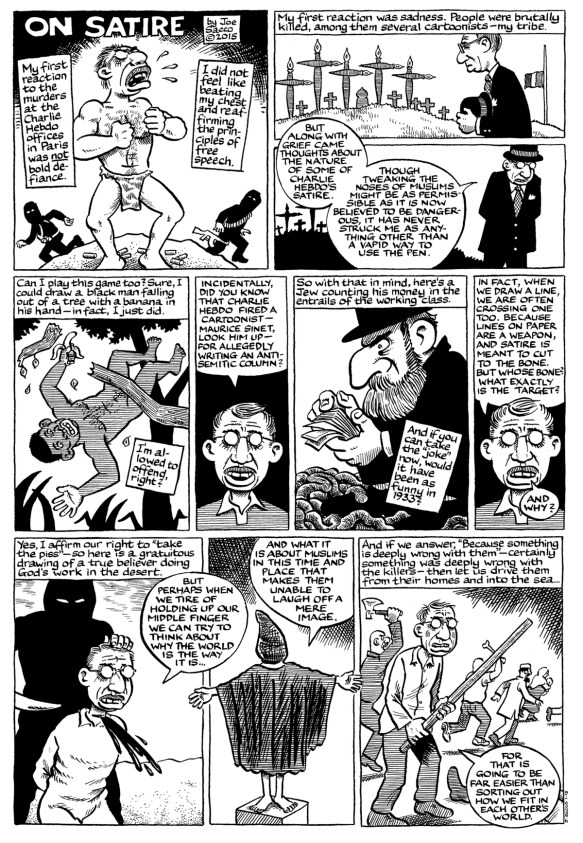

This is, in part, why I haven’t said anything so far about the murders in Paris. But on Thursday I was invited to lead a lunch-time discussion about them at the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies; one of the many wonderful things about the place is the trust that emerges out of a commitment to the irredeemably social nature of intellectual work, and so – beyond the cameras, the microphones and the notebooks – I tried to sort out what I had been reading and thinking. In many ways, it was an extended riff on Joe Sacco‘s cartoon that appeared in the Guardian just two days after the attacks (if you want to know the reactions of Arab cartoonists, then see Jonathan Guyer here and here):

My starting-points were provided by The colonial present. First, many commentators have suggested that the attacks were ‘France’s 9/11’; Le Monde‘s banner headline declared emphatically ‘Le 11 Septembre Français’.

I think this absurd for many reasons, but there are several senses in which the comparison is worth pursuing, particularly if we focus on the response to the attacks in New York and Paris. Both events, or more accurately television and video feeds of the developing situations, were relayed to watching audiences in real time. This sense of immediacy is important, because it says something about the ways in which viewers were drawn in to the visual field and interpellated as subjects who were enjoined to respond – and crucially to feel – in particular ways.

Since this is emphatically not what Dominique Moisi, author of The geopolitics of emotion, had in mind when he insisted that ‘the attacks in Paris and in New York share the same essence’, that both cities ‘incarnate a similar universal dream’ of ‘light and freedom’, perhaps a different comparison will clarify what I mean. Think of the killing of hundreds, even thousands of people by Boko Haram in Baga in northern Nigeria two weeks ago; reports began to appear in Europe and North America just one day after the murders in Paris, but the focus on France remained relentless. There were surely many reasons for that (see Maeve Shearlaw‘s discussion here and Samira Sawlani‘s here), but the contrast between the live feeds from Paris and the scattered, inchoate and verbal reports from Baga is part of it – particularly when you realise that the scale of that distant atrocity was eventually ‘laid bare’, as the Guardian put it, by satellite photographs released by Amnesty International showing more than 3,000 houses (‘structures’) burned or razed in Baga and Doron Baga. For all the importance of surveillant witnessing in otherwise difficult to reach locations, the distance between bodies and buildings, an ordinary camera and a satellite, and live television and static imagery is telling, and sustains an affective geopolitics that is at once divided and divisive.

(Imagery is important to the Paris attacks in another sense too: when the murderers stormed in to the offices of Charlie Hebdo the focus of their rage was a series of cartoons mocking Mohammed – but they were radicalised by quite other documentary images, including coverage of the wars in Iraq and photographs showing the atrocities committed by American troops in Abu Ghraib: see here and here, and look at Joe Sacco’s cartoon again).

My second borrowing from The colonial present was a re-borrowing of Terry Eagleton‘s spirited invocation of ‘the terrible twins’, amnesia and nostalgia: ‘the inability to remember and the incapacity to do anything else’. In the book I suggested that these are given a special significance within the colonial memory theatre, where the violence of colonialism is repressed and replaced by a yearning for the culture of domination and deference that it sought to instill. And in much (fortunately not all) of the commentary on the Paris attacks, France’s colonial past has been effaced. But here is Tim Stanley writing in the Telegraph:

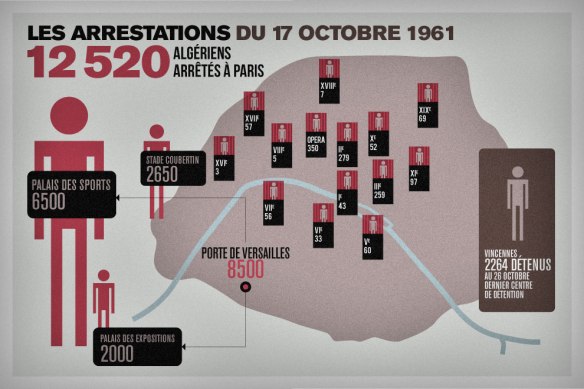

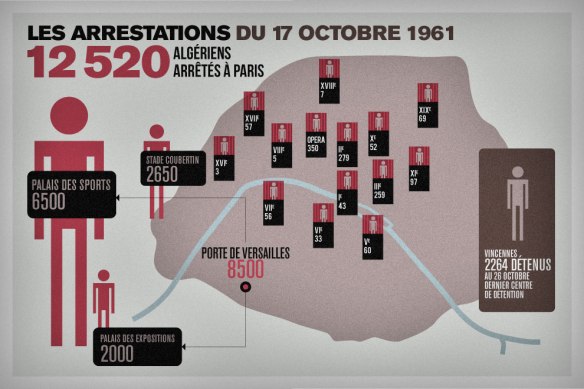

The ability of a society to forget its recent past is like the amnesia that follows an accident – the body’s way of protecting itself against trauma. Yet in the 1950s and 1960s, as France tried to cling on to its African colonial possessions, political violence was far more common than today. Muslim Algerian nationalists (their race and religion regarded as interchangeable by the French) bombed the mainland, assassinated officials and killed colonialists en masse. The reaction of the state was shocking. In 1961, 12,000 Algerian immigrants were arrested in Paris and held in a football stadium [and at other sites: see the map below]. Many were tortured; more than a hundred disappeared. For days, bodies were found floating in the Seine.

You can find more on the events of 17 October 1961 – on the arrests, torture and summary executions following a mass rally to protest against a curfew imposed on Algerians in Paris – here and here, but the definitive account remains Jean-Luc Einaudi‘s Bataille de Paris (1991).

You can find more on the events of 17 October 1961 – on the arrests, torture and summary executions following a mass rally to protest against a curfew imposed on Algerians in Paris – here and here, but the definitive account remains Jean-Luc Einaudi‘s Bataille de Paris (1991).

This is but one episode in a violent and immensely troubled colonial history. To point to this past – as Robert Fisk also did, in much more detail, in the Independent – is to loop back to 9/11 again, when attempts to provide similar contextual explanations were dismissed (or worse) as ‘exoneration’. To be sure, one must be careful: although Chérif and Said Kouachi were the Paris-born sons of Algerian immigrants, Arthur Asseraf is right to reject attempts to draw a straight line between violence in the past and violence in the present. But can the continued marginalisation of Muslims in metropolitan France, particularly young men in Paris’s banlieus, be ignored? (Here there is no better place to start than Mustafa Dikeç‘s work, especially Badlands of the Republic). Doesn’t it matter that more than 60 per cent of prisoners in French jails are Muslims? For the Economist all this means is that jihadists ‘share lives of crime and violence‘ so that structural violence disappears from view, but Tithe Bhattacharya provides a different answer in which the ghosts of a colonial past continue to haunt the colonial present.

This is but one episode in a violent and immensely troubled colonial history. To point to this past – as Robert Fisk also did, in much more detail, in the Independent – is to loop back to 9/11 again, when attempts to provide similar contextual explanations were dismissed (or worse) as ‘exoneration’. To be sure, one must be careful: although Chérif and Said Kouachi were the Paris-born sons of Algerian immigrants, Arthur Asseraf is right to reject attempts to draw a straight line between violence in the past and violence in the present. But can the continued marginalisation of Muslims in metropolitan France, particularly young men in Paris’s banlieus, be ignored? (Here there is no better place to start than Mustafa Dikeç‘s work, especially Badlands of the Republic). Doesn’t it matter that more than 60 per cent of prisoners in French jails are Muslims? For the Economist all this means is that jihadists ‘share lives of crime and violence‘ so that structural violence disappears from view, but Tithe Bhattacharya provides a different answer in which the ghosts of a colonial past continue to haunt the colonial present.

And doesn’t the responsive assertion of a ‘freedom of expression’ that is, again, highly particularistic seek to absolutize a nominally public sphere whose exclusions would have been only too familiar to France’s colonial subjects? Ghasan Hage reads its triumphalist restatement in the aftermath of the Paris murders as a colonial narcissism – a sort of colonial nostalgia through the looking-glass – fixated on what he calls a strategy of ‘phallic distinction’ in which ‘freedom of expression’ is flashed at radicalised Muslims to tell them: ‘look what we have and you haven’t, or at best yours is very small compared to ours.’ (And whose governments have done so much to prop up authoritarian regimes in the Arab world and beyond that thrive on the suppression and punishment of free speech?)

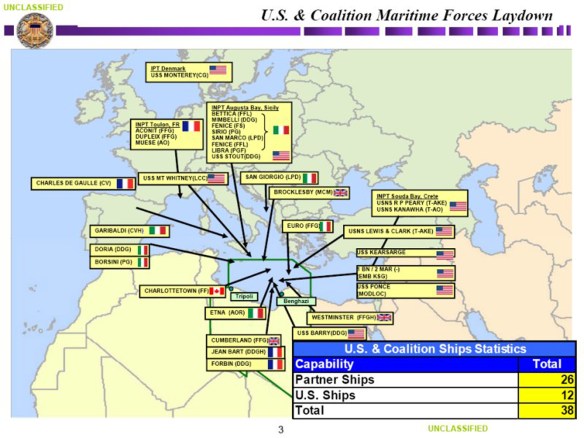

There are, as Joe Sacco’s cartoon makes clear, real limitations on what can be said or shown in France too, including how somebody can present themselves in public – think of the arguments over the veil and the headscarf. There are also limitations elsewhere in the world, of course, which is why the sacularisation of Charlie Hebdo and, in particular, the march in Paris on 11 January seemingly headed by politicians from around the world, arm in arm (in some cases arms in arms would be more accurate), processing down the Boulevard Voltaire (symbolism is everything), was a scene that, as Seumas Milne noted, was beyond satire:

from Nato war leaders and Israel’s Binyamin Netanyahu to Jordan’s King Abdullah and Egypt’s foreign minister, who between them have jailed, killed and flogged any number of journalists while staging massacres and interventions that have left hundreds of thousands dead, bombing TV stations from Serbia to Afghanistan as they go.

True enough, but here too appearance is everything: the photograph was artfully staged (even before one ‘newspaper’ airbrushed the women from the frame) and took place in an otherwise empty side-street.

If I can make one last nod to The colonial present, not surprisingly many of these politicians have also used the murders to justify the continued violence of the wars being fought in the shadows of 9/11; if you are in the mood to reverse the looking-glass, then Markha Valenta‘s sobering reflection at Open Democracy is indispensable:

[E]verything that might be said about revolutionary Islamist movements – when it comes to global violence – could be said about global Americanism and US foreign policy. It has been ruthless, cruel, illiberal, anti-democratic. It has wreaked havoc, killed innocents, raped women, men and youths, tortured viciously, violated the rule of law and continues to do so…

It does so in our name. In the name of democracy. And those who expose this … are shut up ruthlessly, cruelly and in ways designed to degrade. (Yet we did not march then.)

This matters because it clarifies what our condition is today, the condition under which last week’s violence took place: an extended and expanding global war between those who claim the right to intervention, brutality and terror in the name of democracy and those who do so in the name of Islam.

No less predictably, one of the immediate and dismally common responses to the murders, amidst the clamour for freedom of speech, was a renewed call for more state surveillance and regulation. As Teju Cole wrote in the New Yorker,

The only person in prison for the C.I.A.’s abominable torture regime is John Kiriakou, the whistle-blower. Edward Snowden is a hunted man for divulging information about mass surveillance. Chelsea Manning is serving a thirty-five-year sentence for her role in WikiLeaks. They, too, are blasphemers, but they have not been universally valorized, as have the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo.

But it’s not only politicians who are guilty of appropriation. Putting on one (far) side the extraordinary attempts to turn “Je suis Charlie” to commercial account – to ‘trademark the tragedy and its most resonant refrain‘ – there are other, less venal and more complicated appropriations.

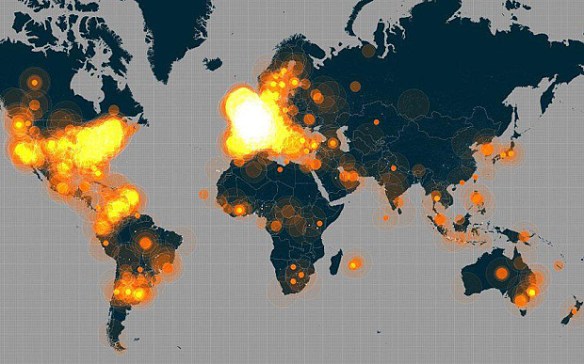

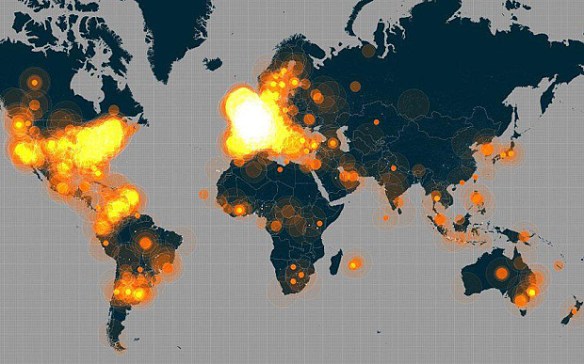

Heat map of #jesuischarlie hashtag; animation is available here

So back to the looking-glass. You might think that “Je suis Charlie” is an affirmative gesture born of anger and horror but also of sympathy and compassion, a simple human reflex that has become virtually commonplace – comparable to, say, “We are all Palestinians“. That was my first thought too. But the trouble is that such a rhetorical claim comes with a lot of baggage. David Palumbo-liu suggests that “I am Charlie” can be an assertion of empathy, solidarity or identification. Even empathy is far from straightforward – why do we extend our fellow feeling to these people and not those? – but, as he shows, the other two progressively raise the stakes. Sarah Keenan and Nadine El-enany wire this to appropriation with exquisite clarity in a short essay at Critical Legal Thinking:

The #JesuisCharlie hashtag and its social media strategy of solidarity through identification with the victim is … an appropriation of what was a creative and subversive tool for fighting structural violence and racist oppression, perhaps most famously in the “I am Trayvon Martin” campaign. When young black men stood up and said “I am Trayvon Martin”, they were demonstrating the persistent and deeply entrenched demonisation of black men which not only sees them killed in the street on their way to the local shop, but also deems their killers innocent of any wrongdoing. When predominantly white people in France and around the world declare “Je Suis Charlie”, they are not coming together as fellow members of a structurally oppressed and marginalised community regularly subjected to violence, poverty, harassment and hatred. Rather, they are banding together as members of the majority, as individuals whose identification with Charlie Hebdo, however well-meaning, serves to reproduce the very structures of oppression, marginalisation and demonisation that allowed the magazine’s most offensive images to be consumed and celebrated in the first place.

As the invocations of Voltaire should have demonstrated, there is a substantial difference between defending the right to draw a cartoon and celebrating what is drawn. Too many commentators clearly want to elide the difference, but there is another distinction to be made too. A Muslim friend who lives in Paris was distraught at the murders, but when he heard the calls for the cartoons to be re-published immediately after the killings he told me he felt brutalised all over again. Those who made such demands, who casually sneered at the ‘cowardice’ of those who failed to comply, either forgot or chose to ignore the existence of a far, far larger Muslim audience than the terrorists against whom they vented their spleen: or, still worse, it never occurred to them that there is a difference between the two.

So: je ne suis pas Charlie; I think I’d rather ‘be’ Joe.

***

I am grateful to my friends and colleagues who helped me think through these issues – I realise there’s a lot more thinking to be done, so please treat this as a first, fumbling attempt – and to Jaimie.