I vividly remember reading Joachim Schlör‘s Nights in the Big City when it was first published almost twenty years ago – an extraordinary reflection on the impact of illumination and the perception of night in Berlin, Paris and London between 1840 and 1930. It joined Wolfgang Schivelbusch‘s elegant Disenchanted Night on my bookshelves, a text whose subtitle – ‘the industrialization of light in the nineteenth century‘ – concealed as much as it revealed the richness of Schivelbusch’s narrative.

I vividly remember reading Joachim Schlör‘s Nights in the Big City when it was first published almost twenty years ago – an extraordinary reflection on the impact of illumination and the perception of night in Berlin, Paris and London between 1840 and 1930. It joined Wolfgang Schivelbusch‘s elegant Disenchanted Night on my bookshelves, a text whose subtitle – ‘the industrialization of light in the nineteenth century‘ – concealed as much as it revealed the richness of Schivelbusch’s narrative.

But even then I thought there was another, later story to tell: what happens when people who have become used to the (more or less) brightly lit city are precipitously plunged back into darkness?

I was thinking of the blackout during the Second World War. This week I’m back at Radboud University in Nijmegen, preparing for a public presentation on aerial violence, and my thoughts have returned to my old question. I think it’s an important one because we know so much about bombing – about crouching under the bombs, seeking cover in shelters, recovering the bodies of the dead and the injured, and then ‘carrying on’ – but we often forget that its horror is not confined to the experience of an air raid, to what Pat Barker memorably describes in Noonday as ‘a stick of bombs … tumbling down the beam of a searchlight onto a building fifty yards ahead, an extraordinary sight, like a worm’s eye view of somebody shitting.’ Others turned to the shattered language of the sublime to capture the aw(e)ful sensation of a city – their city – in flames.

But my point is that these surreal scenes of sound and light and fury were dramatic punctuations in a pervasive atmosphere of anticipation and a larger landscape of terror that together constituted what we might think of as the slow violence of bombing. Sarah Waters captures this (and much more besides) brilliantly in her novel The Night Watch:

‘It was always disconcerting, in a black-out, leaving the places you knew best. A particular feeling started to creep over you, a mixture of panic and dread: as if you were walking through a rifle-range with a target on your back.’

Like Noonday, The Night Watch is the product of careful research as well as a luminous literary imagination; yet historians themselves have made remarkably little of the black-out, content to leave it in the shadows and direct attention to the pyrotechnic displays of the bomber’s art. So what follows are merely notes, and even then confined to Britain, waiting a larger project. (In fairness, there is an important PhD thesis by Marc Wiggam, The Blackout in Britain and Germany during the Second World War (Exeter University, 2011), but his main concerns are policy and policing, and the discussion of cultural formations is largely confined to contemporary literary and film representations and says little about everyday life).

Britain had introduced a limited blackout in 1915, when its cities were menaced by Zeppelins and Gotha bombers. In 1937, keenly aware of Stanley Baldwin‘s bleak injunction in his speech ‘A Fear for the Future’ that ‘the bomber will always get through’, the British government was already making plans for air raid precautions.

Ludgate Circus, London, 11 August 1939

A blackout was introduced in London on 11 August 1939, and a universal blackout imposed on the whole country by a ‘lighting order’ issued under Defence Regulation No 24 on 1 September 1939:

‘… every night from sunset to sunrise all lights inside the buildings must be obscured and lights outside buildings must be extinguished, subject to certain exceptions in the case of external lighting where it is essential for the conduct of work of vital national importance. Such lights must be adequately shaded.’

Felicity Goodall describes how journalist Mea Allan witnessed the introduction of the blackout:

‘I stood on the footway of Hungerford bridge across the Thames watching the lights of London go out. The whole great town was lit up like a fairyland, in a dazzle that reached into the sky, and then one by one, as a switch was pulled, each area went dark, the dazzle becoming a patchwork of lights being snuffed out here and there until a last one remained, and it too went out. What was left us was more than just wartime blackout, it was a fearful portent of what war was to be. We had not thought that we would have to fight in darkness, or that light would be our enemy.’

It was, as Geoff Manaugh notes, ‘a different form of camouflage, one that hid the city against the surrounding landscape by plunging its streets and buildings into darkness.’

Households were required to make special blackout curtains; they could not be washed, because this would let the light through, so housewives (sic) were enjoined to ‘hoover, shake, brush then iron them.’ The windows had to be closed to secure the blackout too, so rooms soon became airless. Chris Hill has the reaction of a teenage girl living in Romford, recorded in her diary for Mass Observation:

Friday 1st September – “…our makeshift blackout arrangements involve the use of a light so small that it strains the eyes. It’s only ten but I’m going to bed.”

Sunday 3rd September – “I decided we could not stop indoors; the blackout curtains made the rooms stuffy, and the light bad. We went into the town ‘to see what was going on’… Evidently, others had come out for similar reasons, so every street corner was ornamented with little groups of people…”

In short order a new city of ‘dreadful night’ was conjured into being. John Lehmann later recalled that

‘London had become two cities. The one, the daytime city where we went about our business much as before, worked in our offices and discussed what plans we could make for the future… The other London was the new, symbolic city of the blackout, where one floundered about in the unaccustomed darkness of the streets, bumping into patrolling wardens or huddled strangers…’ [cited in Amy Helen Bell, London was ours: Diaries and memoirs of the London Blitz].

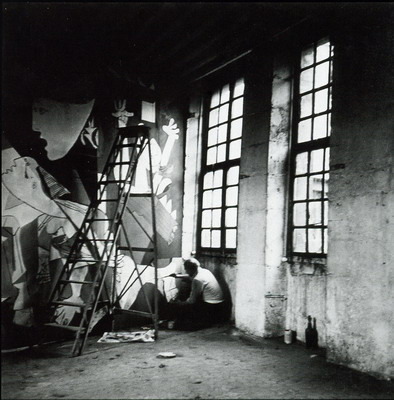

Blackout (Art.IWM ART LD 2913) image: Night scene of a city street with pedestrians carrying torches, a vehicle with masked headlights and a very dim

street light. The shapes of darkened buildings can be seen lining the street. Copyright: � IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/5477

The sensibility Lehmann describes – the floundering and bumping about and the attendant disorientation and disorder – may explain, in part, why war artists made so few attempts to capture the blackout. This was not, as you might think, simply or even primarily the product of a collective reluctance to produce a near-black canvas. In his War Paint, Brian Foss remarks that, ‘despite its status as the most universally experienced aspect of home front life,’ the blackout

‘is the subject of a mere handful of war pictures. Of these, only one, purchased from Joan Connew [above], a hitherto virtually unknown painter from Kent, exploits both the rich tonal potential and the incipient visual confusion of a blanket use of brown and blacks.’

He argues that the absence from the War Artists Advisory Committee of blackout paintings was the product of a sort of counter-blackout that expressed ‘the psychological need for orientation points and beacons.’

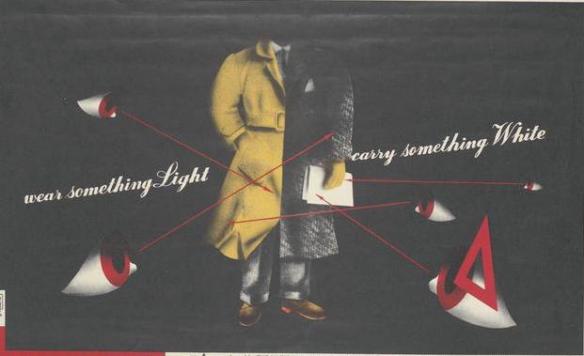

So as the blackout was carefully calculated and disseminated (above), I think it important to register the attempts to impose an order upon and within its envelopment of the city.

Street lights were switched off, and drivers of vehicles had to mask their headlamps using thick cardboard discs, obscure all other lights to the side and rear, and mark their bumpers and mudguards with white paint. Sarah Waters imagines roads even in the capital becoming almost empty – she’s writing about Holborn – ‘with ‘only the occasional cab or lorry – like creeping black insects they seemed in the darkness, with gleaming, brittle-looking bodies and louvred, infernal eyes.’ That wasn’t a pure flight of the novelist’s imagination. Pedestrians had to mask their torches too, and Mrs Peg Cotton confessed that, as she walked home one night,

‘The tissue came off my torch and since the light is prohibited thus, I hid it under my coat. The light shining out from below my skirts thus made me look like a crawling lightening-bug’ [in Felicity Goodall, Voices from the Home Front]

The blacked-out city was an unfamiliar one but also a dangerous one. ‘The density of the blackout these cloudy moonless nights is beyond belief’, recorded Phyllis Warner:

‘No one in New York or Los Angeles can successfully imagine what it’s like. For the first minute going out of doors one is completely bewildered, then it is a matter of groping forward with nerves as well as hands outstretched’ [Goodall, Voices]

When leaving the dimmed but illuminated interior of a house, a railway or a tube station, travellers were advised to close their eyes and count to fifteen to prepare for the abrupt plunge into darkness.

Here is Sarah Waters:

As she opened the door she said, ‘I hate this bit. Let’s close our eyes and count, as we’re supposed to’—and so they stood on the step with their faces screwed up, saying, ‘One, two, three …’ ‘When do we stop?’ asked Helen. ‘… twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen—now!’ They opened their eyes, and blinked. ‘Has that made a difference?’ ‘I don’t think so. It’s still dark as hell.’

As that vignette suggests, the very choreography of the city was altered and even regulated. So, for example, pedestrians were advised to wear white at night (gloves, hats, armbands, buttons: Selfridge’s did a roaring trade in selling ‘blackout accessories’) –

– and they were instructed to walk on the left to avoid colliding with one another:

It was even more difficult for drivers, especially those rushing to provide emergency help at the scene of an air raid. Again, Sarah Waters is brilliant at conjuring the experience of her volunteer ambulance drivers during the Blitz. Often, the flames cut through the darkness to provide hideous illumination. ‘You didn’t need any lights or maps to find the way,’ one City of London fireman observed, ‘you just headed for the glow in the sky’ (below).

But it wasn’t always so simple. Here’s another firefighter:

‘It’s no joke finding your way about in a vehicle during the blackout through back streets in a district you and your driver have never been in before! As we were now some distance away from the fires, and Jerry being overhead, we were proceeding without lights – except side lights which are so dimmed as to be useless for illuminating the road. The pump in front of us had turned round a corner. We followed and suddenly the tender bumped, lurched and went along with two wheels on the pavement. We had only just missed dropping into a crater about twenty feet across by ten to fifteen feet deep. The first pump had swerved the other way from us and was stuck with its nose in a heap of debris’ [Goodall, Voices]

By the beginning of 1940 more people had been killed in road accidents than by enemy action. Ironically one of the first was a council employee hit by a vehicle as he painted a white line on a curb near Marble Arch – these lines, marking curbs and steps, were intended to help people navigate the darkened city.

In addition, as Geoff Manaugh demonstrates, both the flow and the fabric of the city were reconfigured: a 20 m.p.h. speed limit was imposed, blue lights marked public air raid shelters, and new white markings appeared on roads to guide the traffic:

Unusual markings in the roadway at Piccadilly designed to help motorists at night during the blackout in World War II. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

You can find more photographs of London during the blackout at mashable here and, of course, via the Collections page of the Imperial War Museums.

The imposition of the blackout was remarkable successful – though once the flares and the bombs sailed down, the bombers quickly found their mark (if rarely the precise target they were aiming for). So let me leave you with this exquisite exchange that captures the interplay between the blackout and the bombs; it comes from John Strachey‘s account of his days as an ARP warden, Digging for Mrs Miller:

‘As he put his head out, a man said “Warden,” out of the dark. “Warden”, went on the voice irritably, “Come and see these dreadful lights. Don’t you think you ought to put them out at once?” Ford went down the street a few yards and found a man in a trilby hat pointing towards the trees in Bedford Court. There were the lights all right, two of them behind the trees, and as they watched three more came slowly drifting and dropping through the higher sky, red, white and orange. “I’m afraid I can’t put those lights out,” Ford said. “You see, those are flares dropped from German aeroplanes.”